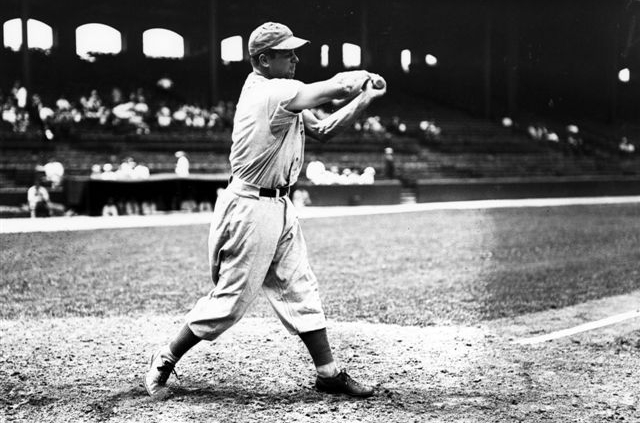

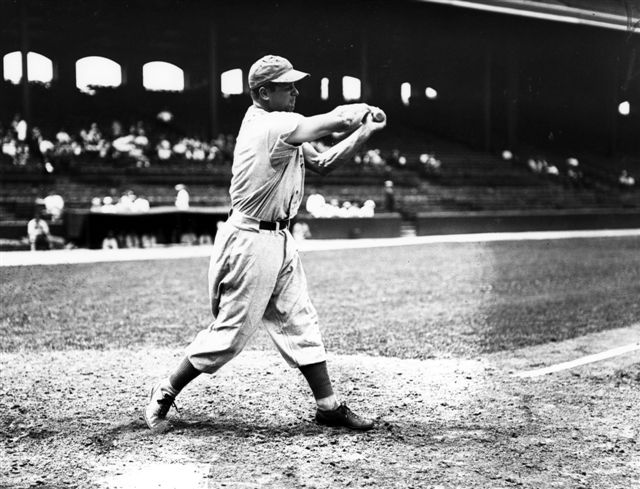

Double X and His Lost Dingers

This article was written by Robert H. Schaefer

This article was published in Spring 2013 Baseball Research Journal

In the baseball season of 1932, Jimmie Foxx—known then and now as Double X—made a concerted assault on Babe Ruth’s home-run record of 60 in a season. The Philadelphia A’s strong boy came up two short, ending his season with a total of 58. There is a persistent legend that Foxx would have broken Ruth’s record had fate not intervened. The root of this legend is found in Sportsman’s Park. Erected in 1909 and opened only days after Philadelphia’s Shibe Park, it was the second park in the steel-and-cement stadium era. Sportsman’s Park was used by both the National and American League teams in St. Louis from 1920 until the end of the 1953 season, when the Browns’ new owners moved the club to Baltimore and changed their name to the Orioles.

The cozy dimensions of Sportsman’s Park were a hitter’s delight, especially for left-handed power thumpers. The right-field foul line was only 310 feet from home plate and the outfield fence curved gently to an affable distance of 348 feet in straightaway right field. In order for a batted ball to leave the field of play and land in the grandstand for a home run, it had to clear an 11.5-foot high cement wall. During the first week of July 1929, the visiting Tigers hit a total of eight home runs in four games at Sportsman’s Park, humiliating the hapless Brownies. No game was scheduled for the following day, July 5.

The cozy dimensions of Sportsman’s Park were a hitter’s delight, especially for left-handed power thumpers. The right-field foul line was only 310 feet from home plate and the outfield fence curved gently to an affable distance of 348 feet in straightaway right field. In order for a batted ball to leave the field of play and land in the grandstand for a home run, it had to clear an 11.5-foot high cement wall. During the first week of July 1929, the visiting Tigers hit a total of eight home runs in four games at Sportsman’s Park, humiliating the hapless Brownies. No game was scheduled for the following day, July 5.

The next team scheduled to call in St. Louis, the New York Yankees, featured several powerful left-handed hitters who had acquired a reputation for blasting home runs, not the least of whom was The Babe himself. The outlook for the Brownies was grim. Fearing the worst, on the offday Browns team president Philip de Catesby Ball had a screen erected in front of the right-field pavilion. The new screen stretched from the right field foul pole some 156 feet towards center field. The 21.5-foot tall screen was suspended from the pavilion roof and descended to the top of the outfield wall. The screen effectively denied a huge portion of the right-field stands to home-run hitters. A batted ball now had to clear a 33-foot high barrier. This modification was designed to prevent cheap home runs by the opposition. President Ball evidently believed that the anemic Browns would be less affected by the screen than all other American League teams.

Regarding the first game after the screen’s installation, the Cleveland Plain Dealer reported:

St. Louis, July 7. The first move to cut down the assault of home run hitting showed its effect in today’s game between the Browns and the Yankees when five drives landed against the right field screen ordered in front of the pavilion seats yesterday by President Ball of St. Louis. Ruth lost a homer in the fourth when his liner hit the screen. The Babe showed his disgust and waved gestures toward the outfield screen. Heinie Manush lost three home runs and Fred Schulte one.

The irony of the screen’s effect is that it hurt the Brownies more than the Yankees by a 4-to-1 margin. Nonetheless, the screen remained in place until the 1955 season. Because the Cards’ line-up that year had a disproportionate number of left-handed hitters, both Manager Eddie Stanky and General Manager Dick Myer thought the screen would hurt the team and they had it removed.1 The next year, new General Manager Frank Lane restored the screen when it became apparent that the opposition was helped more than the Cards. The screen stayed in place for the remainder of Sportsman’s Park’s tenure as a major league ball park.

Obviously, when The Babe smashed his record sixty home runs in 1927 the screen wasn’t a factor. One source indicates that the Babe hit only four home runs at Sportsman’s Park in 1927, but does not indicate to which parts of the field the Babe made his homers.2 How much the screen would have reduced his 1927 record is an interesting question, but is not relevant to the legend involving Double X. The issue at hand is to determine the number of home runs, if any, that Jimmie Foxx “lost” due to the right-field screen. Let’s first survey what other baseball writers have stated:

Glenn Dickey, in his book, The History of the American League, reports that Foxx lost three home runs due to the wire netting above the regular fence in St. Louis.3

St. Louis sportswriters Bob Broeg and William J. Miller, Jr., in their book, Baseball From a Different Angle, report the following information concerning Foxx’s encounter with the right-field screen: “By Reidenbaugh’s research … Foxx hit the right-field screen 12 times at Sportsman’s Park [in 1932] and the ball was in play.”4

Lowell Reidenbaugh was a senior editor at St. Louis’s famous weekly journal of baseball, The Sporting News, and conducted this research for his book entitled Take Me Out to the Ball Park. Having made the startling claim of twelve lost dingers, Broeg and Miller then tempered this number: “Actually, as Reidenbaugh acknowledged, the research was questionable.”

Gene Mack also suggests that Foxx smacked 12 would-be home runs into the netting in 1932. He attributes this number to an unnamed Philadelphia scribe.

Next, Broeg and Miller quote Broeg’s own book, Super Stars of Baseball, which gives Foxx’s number of lost home runs as seven. They additionally report that this is the same number claimed by Foxx himself in a 1964 interview with St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter Neal Russo. Broeg and Miller muddied the waters still further by stating that some unnamed researchers determined that Foxx lost “only” four home runs to the screen in 1932.

This survey of published but unconfirmed reports of Foxx’s lost home runs ranges from a low of three to a high of twelve, making Foxx’s 1932 potential home run total without the intervention of Mr. Ball and his infamous screen a minimum of 61 and a maximum of 70. Either number would have defeated Ruth’s record 60 of 1927. If in fact Foxx had not lost these home runs, Roger Maris would not have been able to surpass him in 1961. What is the actual truth? Just how badly was Foxx hurt by the installation of the right-field screen?

The best place to begin this inquiry is to examine the batter-by-batter accounts of the eleven games Foxx played in Sportsman’s Park in 1932. The A’s arrived in St. Louis for a five game series and played the first game on June 15. Right-hander Irving “Bump” Hadley was the Brownies’ starting pitcher. Foxx struck out in both the first and third innings. He then singled to left in the fourth, driving in Bishop and Cramer. Foxx doubled off the right field screen in the sixth. The A’s rallied in the seventh and Walter “Lefty” Stewart came in to pitch for the Brownies. In his last time at bat with Stewart pitching, Foxx drove a long fly to center field. Schulte pulled down this drive near the flag pole. Foxx was 2-for-5 in this game, a single and the lone double off the right field screen.

The next day left-handed pitcher Carl Fischer started and completed the game for St. Louis. In the first inning Foxx popped up to shortstop Levey. He then struck out in the third and walked in the fifth. In his last at bat Foxx grounded into a double play, shortstop Levey to second baseman Melillo to first baseman Burns. Foxx was 1-for-4 with a walk and a single on the day.

The next day left-handed pitcher Carl Fischer started and completed the game for St. Louis. In the first inning Foxx popped up to shortstop Levey. He then struck out in the third and walked in the fifth. In his last at bat Foxx grounded into a double play, shortstop Levey to second baseman Melillo to first baseman Burns. Foxx was 1-for-4 with a walk and a single on the day.

After an off-day, the series resumed on June 18. Right-hander George Blaeholder started for St. Louis. In the first inning Foxx grounded to third baseman Grimes, who threw him out at first. Blaeholder struck out Foxx in the third. Left-handed Wally Herbert replaced Blaeholder in the fourth inning and Foxx flied out to Campbell in right field to end the inning. Herbert gave way to right-hander Chad Kimsey. Foxx grounded into a double play, Levey to Melillo to Burns, in the seventh for his final at bat. He went 0-for-4.

The A’s and Browns played a double header on June 19. Bump Hadley pitched a complete game in the opener for St. Louis, beating the A’s, 3–2. Foxx went 1-for-3, a single. He also had two walks.

Stewart started the second game for St. Louis but lasted only 21?3 innings. James C. Isaminger described the events in the Philadelphia Inquirer:

In this game Jimmy Foxx drove Lefthander Stewart to the showers in the third inning with a cyclopean round tripper.

In lashing out his 26th homer of the season Foxx gave the spectators a thrill, for he drove the ball out of the park east of the scoreboard for the first time in history.

Only twice has the ball been hit out of the park in this section before and both went over close to the foul line, a shorter wallop. Foxx’s record-breaking belt cleared the entire depth of the bleachers sardined with coatless customers and left the park ten feet above the outer wall. Veteran St. Louis baseball writers gasped when they saw the hit and declared that it was the longest homer ever made in St. Louis.

Two were on base when the broadback made this cyclopean crack.

How far did this “record” home run travel on the fly? When queried on the possible length of this home run, ballpark historian and design consultant John Pastier wrote in an e-mail:

A diagram I have shows the depth of the bleachers to be about 45′, which is generally confirmed by the number of rows (about 20) in a photo in Take Me Out to the Ballpark.

If the ball was just to the east of the edge of the scoreboard, it would have to travel at least 440′ to reach the rear wall (about 390′ at the playing field wall), which I estimate to be about 28′ high. This indicates a minimum of about 454′ necessary to just clear the wall. Adding the 10′ of extra height would make the minimum about 459′. The questions then are whether the ball’s arc was flatter than a very high fly (very unlikely for a ball hit that far), and how far east of the scoreboard it was.

By the way, there’s no way an observer in the pressbox would be able to tell how high the ball was when it cleared the back fence—that vantage point would be well over 500′ away and not permit good depth perception…I’d guess that the ball came to earth about 460′ to 475′ from home plate, which is still very impressive.

Foxx added a single to his day’s work, giving him 2-for-4. This closed out the A’s three-game series in St. Louis. The A’s returned on August 4 for another three-game series. Stewart started the first game and pitched a complete-game victory, winning 6–2. Leading off the second inning, Foxx singled to left field, then walked in the fourth, and grounded out Levey to Burns in the sixth. In the eighth Foxx hit into a double play, Levey to Melillo to Burns. In the ninth he hit a hot liner directly to Goose Goslin in left, who grabbed it for the out. In this game Foxx went 1-for-4 with a walk.

The game played on Friday, August 5, ended after ten innings, with the Browns winning 9–8. Hadley, Sam Gray, and Fischer all pitched for the Browns. Foxx walked in the first and third innings, then hit a single to left field in the fifth inning, scoring Mule Haas and Mickey Cochrane. Foxx went 2-for-3 with a home run and 2 walks. On Saturday Blaeholder pitched a complete game as the Browns lost, 4–2. Foxx went 0-for-4, grounding out three times—to second base in the second, third base in the third, short in the sixth—and finally struck out in the ninth.

The A’s returned to the Mound City on Wednesday, September 14, for their final series. In the first inning Foxx singled past Scharein at third base. In the third he forced Simmons at second base, Levey to Melillo. He walked in the fifth. In his final at bat Foxx popped out to Rick Ferrell in front of the plate in the seventh. Foxx was 2-for-5. The next day Foxx popped up to Burns at first base in the second inning, fouled out to Burns in the fourth. He singled to center in the sixth, and grounded out to third in the ninth. Foxx was 1-for-4.

Friday, September 16, marked the A’s last game at Sportsman’s Park in 1932. Foxx walked in the first and third innings, and grounded out to Burns at first base in the sixth. He ended his 1932 appearance in St. Louis by ignominiously striking out in the eighth inning, 0-for-2 on the day.

A summary of Foxx’s 11 games at Sportsman’s Park in 1932 produces a batting average of .225, OBP .326, and SLG .300. These statistics are wan in contrast to Foxx’s overall batting average of .364 and slugging average of .749. For comparison, the American League posted a batting average of .277 and .404 slugging in 1932. In 1932 Sportsman’s Park was not Double X’s favorite place to hit a baseball. His overall sub-par performance there is consistent with the fact that Foxx hit only one ball into the right field screen, and that came in the A’s first game of the series on June 15.

So there you have it. Without the screen in right field, Foxx would not have broken Ruth’s home run record in 1932. But the story of Foxx’s 1932 lost dingers doesn’t end in St. Louis. Listen to what Foxx told writer Joe Williams on the subject in 1940, not about Sportsman’s Park, but Shibe:

I came close in 1932, you know. As a matter of fact, I actually did break it, but a barbed-wire arrangement set up outside Shibe Park to keep kids from climbing the fence blocked me. I hit three balls that were outside the park; they hit the wire and bounced back on the field. They were just as legitimate as any of the other 58 home runs I hit but they didn’t count.5

It is unlikely that this information was noted by any local reporters as part of the daily game account to either verify or deny it. But if we take Foxx’s tale at face value, we then have to add three home runs “lost” at Shibe Park which increases his actual total to 61. And if we stretch the point a bit further and remove the right-field screen from Sportsman’s Park, Double X ends up with a season total of 62. So which record did Roger Maris break in 1961?

BOB SCHAEFER retired to a small island off Florida’s west coast after a 40-year career in the aerospace industry. He has specialized in researching 19th century baseball. The results of his research have been published in the “Baseball Research Journal,” “The National Pastime,” “NINE,” and “Base Ball: The Early Years.” His work has been recognized with the McFarland-SABR Award for best baseball research in three separate years.

Notes

1 Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals, (Walker and Company, 2006), 31.

2 Gene Mack, Hall of Fame Cartoons of Major League Ball Parks, (The Globe Newspaper Company, 1947).

3 Mack, 108.

4 Mack, 46.

5 Jimmie Foxx, quoted on March 15, 1940, during spring training in Sarasota, Florida in a column written by Joe Williams on that date. Peter Williams, Ed. The Joe Williams Baseball Reader, (Algonquin Books, 1989), 93.