Ed Barrow, the Federal League, and the Union League

This article was written by Daniel R. Levitt

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 28, 2008)

Hall of Fame executive Ed Barrow secured his legacy during his years with the Yankees. He joined New York’s front office after the 1920 season as their first de facto general manager. The next year the team won its first pennant; during his 24-year tenure, from 1921 through 1944 (through 1947 he stayed on as chairman of the board, but the position was largely honorary), New York won fourteen pennants and ten World Series championships. Barrow had apprenticed well for the Yankee position, having spent nearly his entire adult life in baseball holding almost every conceivable job, including scorecard hawker.

From 1911 through 1917 he served as president of the International League, designated (along with the American Association and the Pacific Coast League) as the highest-classification minor league. The International League consisted of many of the largest northeastern cities in North America that did not have a major-league team: Baltimore, Buffalo, Jersey City, Montreal, Newark, Providence, Rochester, and Toronto. Three of these cities—Baltimore, Buffalo and Providence—had an ex- tended run with a major-league team in the nineteenth century.

During the early years of his tenure as president, the International League was profitable and successful. In 1913, however, a new outlaw league, the six-team Federal League, began operation in a number of larger cities in the Midwest. Its players came from outside of Organized Baseball, and so most baseball owners initially remained aloof. The Federal League’s teams consisted predominately of local semipro players, aging ex-major-leaguers, and journeyman minor-league veterans. Late that first sea- son, the Federal League decided to expand to eight teams, invade some larger eastern cities, and challenge the existing order as a third major league. To compete, the Federals assembled a financially strong group of owners that compared favorably with the major leagues.

At the time minor-league franchises were generally owned by baseball men and politically connected businessmen of unexceptional wealth. The owners in Barrow’s International League were at a significant disadvantage when confronted with a league backed by some of America’s wealthy industrialists. The problem manifested itself most acutely in the two markets competing directly with the new league, Baltimore and Buffalo. In Baltimore, the team was owned by Jack Dunn, a brilliant baseball operator but with few financial resources outside his franchise. Buffalo president J. J. Stein headed up one of the league’s most poorly capitalized franchises.

The other International League franchises were also insufficiently capitalized for a drawn-out battle. Newark and Providence were owned by major-league interests. A syndicate led by Charles Ebbets, owner of the Brooklyn Robins (as the Dodgers were then called), controlled the Newark franchise, and a Detroit group including William Yawkey, Frank Navin, Ty Cobb, and Hugh Jennings owned the Providence club. Because of the impact of the Federals on their major-league teams, neither—particularly Ebbets—had extra funds available to expend in defense of their International League franchises. A corporation that included Bill Devery, part owner of the Yankees and a shady former New York police chief, controlled the Jersey City club. The other three franchises, Toronto, Montreal, and Rochester, were principally owned by baseball men of modest means.

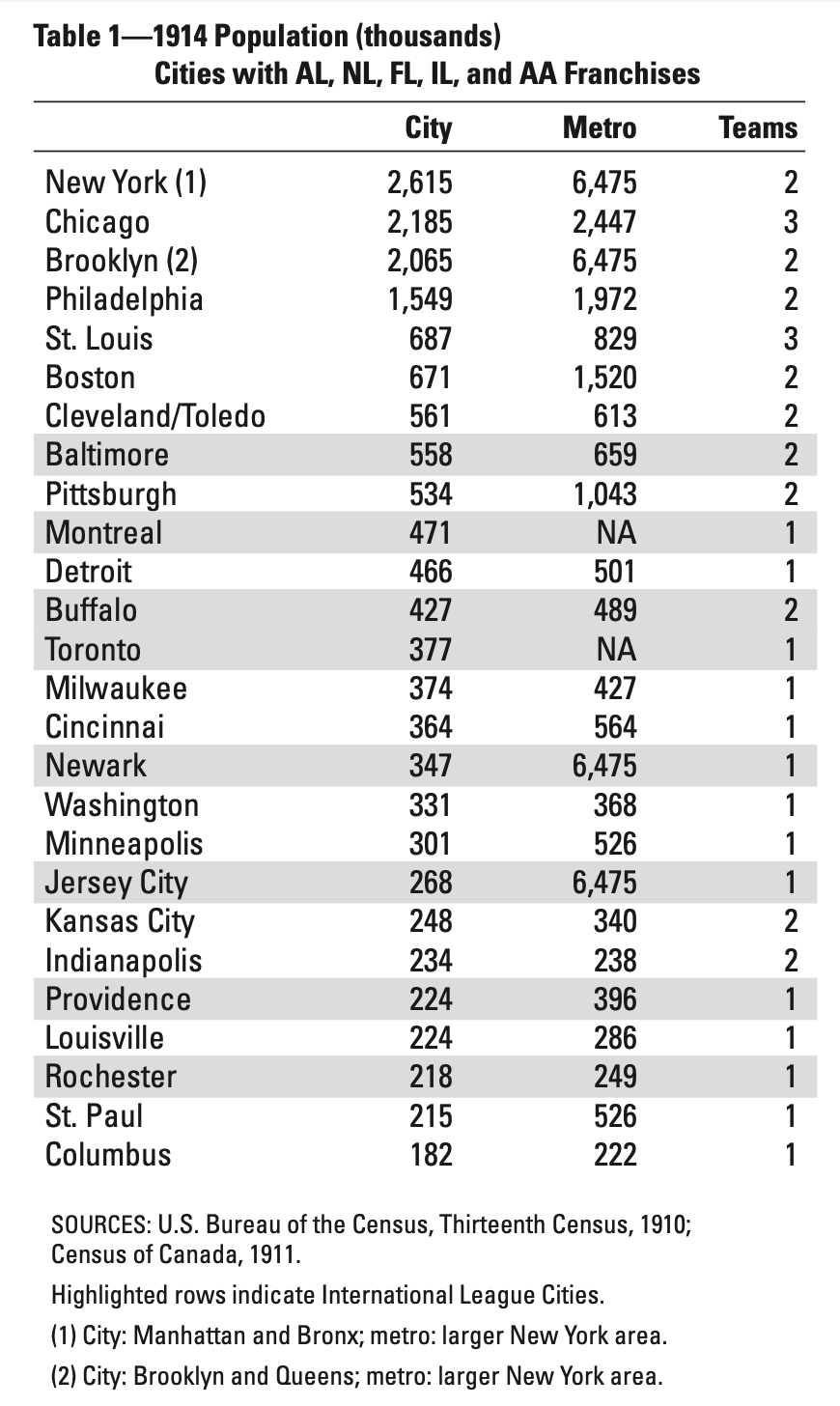

To add some perspective, Table 1 summarizes the various market sizes in 1914. The chart underscores how competitive the Federals made the struggle for fans in a number of cities. Furthermore, it highlights that in Baltimore, Buffalo, and Toronto, the International League was in some of the largest North American cities. (As to Montreal, despite its size, it was a perennially struggling franchise.)

Table 1—1914 Population (thousands)

Cities with AL, NL, FL, IL, and AA Franchises

(Click image to enlarge)

At their December 1913 winter meetings, Barrow and his owners discussed ways of countering the threat from the Federal League. The American Association advocated a plan to end the regular season after 112 games and then play an interleague series with the International League. The International League owners, however, feared that fans would have little interest in a bunch of exhibition games after the regular season and turned down the proposal.

The International League and American Association also petitioned the major leagues to eliminate the major league–minor league draft. The draft had long been a sore spot between the high minors and the major leagues. It allowed teams to select players—for a meaningful but not particularly generous fee—from a lower classification league. The exact draft rules changed often, but in general a team could lose one or two players in a season. Owners and fans in the high minors often resented being cast as second best, and the bitter confrontation with the Federals, who promoted themselves as major, exacerbated this problem. Barrow hoped to rescind the draft, at least during the battle with the Federal League. Although sympathetic to the plight of the minors, the major-league magnates never agreed to Barrow’s request. Many felt that eliminating the draft was tantamount to conferring major-league status, further diluting their own monopoly. Additionally, the draft provided a source of relatively inexpensive, well-trained talent.

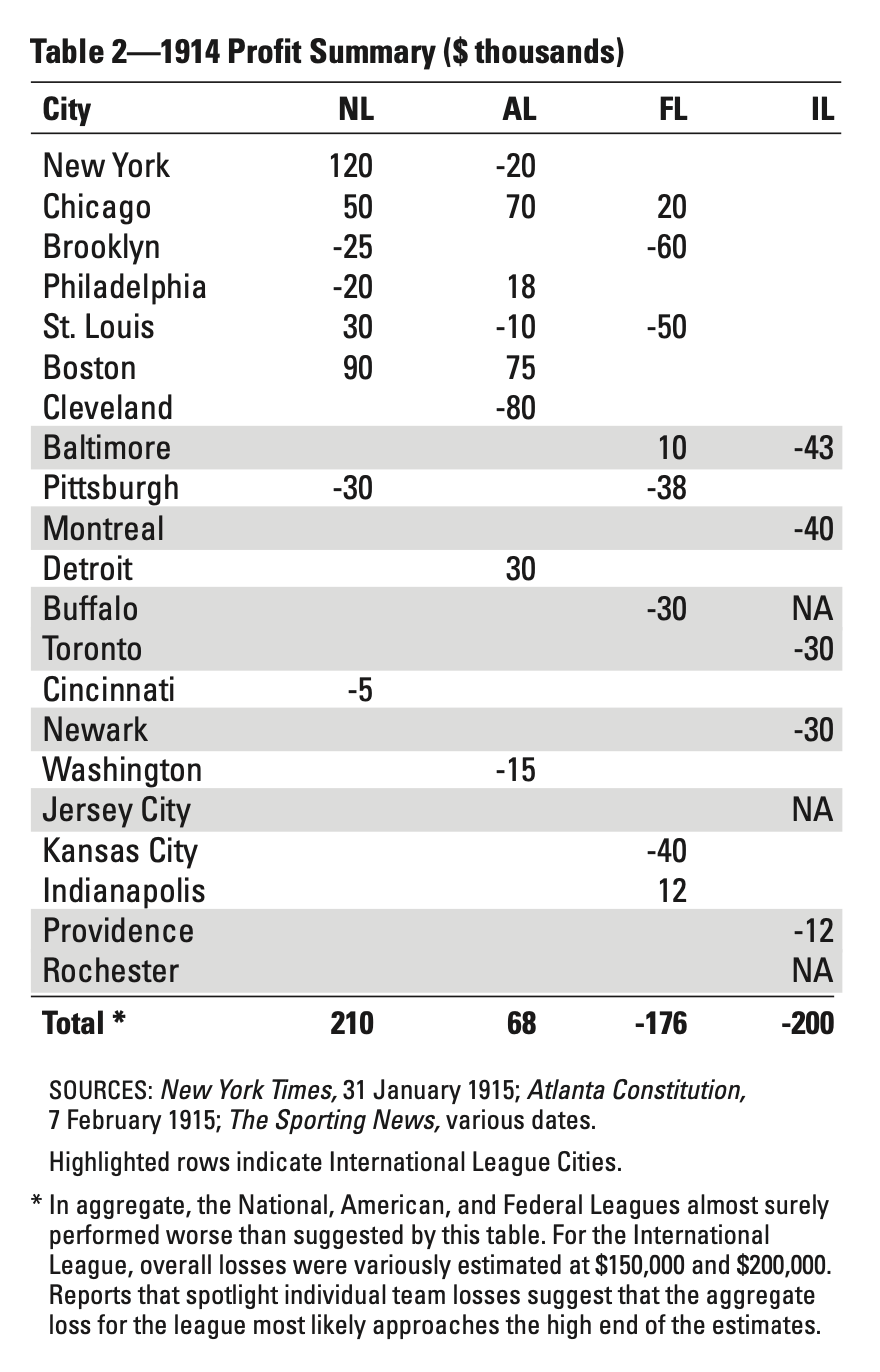

Despite Barrow’s best efforts, by June it was clear that the International League was in big trouble. Table 2 summarizes the overall 1914 losses.

Table 2—1914 Profit Summary ($ thousands)

(Click image to enlarge)

Clearly, the modestly capitalized International League teams were in severe financial distress. (These figures are from several newspaper accounts, and the National League figures in particular are probably exaggerated to the high side; it is highly unlikely that any league, in aggregate, turned a profit in 1914.) Jersey City, though not in direct competition with the Federals, was drawing only 200 to 500 fans per game. In Montreal the players were so disgusted with the poor attendance that they sent a delegation to petition owner Sam Lichtenhein to either trade them or sell the club. The players later complained that they could not “play winning ball in that city,” and warned they might strike if the franchise was not transferred. In Newark, President Charles Ebbets Jr. had to borrow $2,000 from his father to meet payroll. Rochester’s week-day games drew only 800 to 1,200 patrons, compared to 2,000 to 3,000 in previous years. But it was in Baltimore that the crisis manifested itself most acutely. Despite the team’s first-place showing, at the gate the fans overwhelmingly chose the putative major-league Federals over the International League.

On June 20, 1914, Barrow led a delegation that included Dunn, Stein, and J. J. McCaffrey and Joe Kelley from Toronto to a meeting at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel with the National Commission to plead for some relief from the mounting losses. In the period before the current commissioner system, Organized Baseball was governed by the National Commission, a three-man panel consisted of the two league presidents and chair- man Garry Herrmann, president of the Cincinnati Reds. Barrow and his owners lobbied for either financial sup- port or an elevated status for the International League through the elimination of the draft and other changes.

Barrow, Dunn, and company were surprisingly successful and received provisional support from the commission to create a third major league within the Organized Baseball structure. American League president Ban Johnson, first among equals on the National Commission and the most powerful man in baseball, announced after the meeting:

There will be a third major league, and I think it will be a good thing for the peace of Organized Baseball. It is true that the commission has not formally ratified the new project. But that is only a question of formality. We will now see how far the Federal League can go against real major league opposition on every hand. Let me tell you the new circuit will soon prove its merits over the so-called class of Gilmore’s league. (James A. Gilmore was the Federal League’s president.)

The principal scheme for the third major league involved peeling off the four strongest markets from the International League—Baltimore, Buffalo, Toronto, and Newark—and merging them into a new league with four from the American Association, most likely Indianapolis, Toledo, Milwaukee, and either Minneapolis, Louisville, or Columbus. The remaining franchises in the two class AA leagues would then be formed into a new minor league.

An alternative proposal floated from the meeting had the new league placing new, Organized Baseball-sanctioned teams in existing major-league cities. In this version Baltimore, Buffalo, and Toronto would be joined by other International League and American Association franchises transferring into the major-league cities of Detroit, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland, with Newark potentially moving to Washington. The latter alternative never had any chance of success. No major- league owner would voluntarily permit another major-league team in his city, even assuming the game dates could be scheduled to eliminate conflicts. (For example, to discourage the Federal League from invading his city, Charles Somers, owner of the Cleveland American League franchise, moved the Toledo American Association franchise, which he also owned, to Cleveland to present a full slate of baseball games.)

Unfortunately for Barrow and Dunn, the entire third-major-league idea died quickly over the next couple of weeks. As the plan reached a wider audience, strong opposition developed among a number of interested parties. A few major-league owners were mildly receptive, but most were hostile to the idea of adding a third major league to the already fierce competition for fans and players. Moreover, the American Association owners had not been consulted in advance and showed little interest in the proposal. Indianapolis and Kansas City—the two American Association teams competing directly with the Feds—had fared tolerably. Many of the other franchises were certainly losing money, but most owners felt the situation was not dire enough to warrant the dissolution of their league.

As their hopes died, Barrow and the potentially major-league International League cities felt betrayed and disappointed. Barrow naturally had hoped to found a new, solvent major league, of which he would be president. The other members of his delegation thought they were on their way to becoming major- league owners.

In retrospect, it is hard to gauge whether the third- major-league option was ever feasible. In any case, Barrow and Johnson failed to manage the political side of the issue with any sensitivity. Such a radical step required backroom lobbying with both major-league and American Association owners well in advance of any announcement. That consensus-building was not a strength of either Barrow or Johnson seriously impeded any scheme for a new, third major league.

Despite the financial hardships, Barrow held the eight-team International League together through the end of the season. He restructured the ownership in Buffalo and relocated the Baltimore franchise to Richmond. In 1915, though, the struggle grew increasingly desperate. Over the second half of the season Barrow not only had to manage his league’s affairs; he was also essentially running the Jersey City and Newark franchises, which had been forfeited to the league When the season ended the International League was still intact—but just barely. Relief appeared when, during the offseason, the Federal League agreed to a buyout of its franchises by Organized Baseball.

But the demise of the Federal League was no guarantee that the next year would be a prosperous one for the International. By the end of the 1916 season, none of the teams had banked more than a token profit. In aggregate, the league’s franchises lost another $100,000 in 1916, and many were in severe financial distress. The owners were now more restless than ever about the major league–minor league draft. As major-league attendance recovered, the high minor leagues strongly resented the price-depressing effect that the draft placed on player sales. In the fall of 1916, the ongoing financial troubles of the International League led to another revival of discussion about a third major league. Once more the new major league would consist of some amalgamation of the International League and the American Association. In an interview after the 1916 season, American League president Ban Johnson remarked that he “rather liked the idea” of a third major league.

Johnson was not really advocating for a third major league but simply offering a casual opinion. He may also have been posturing for the benefit of Organized Baseball in the lawsuit filed by the owners of the Baltimore franchise in the Federal League. (The Baltimore owners had rejected the settlement dissolving their league and sued Organized Baseball for violation of the antitrust laws. This lawsuit, Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore, Inc. v. National Baseball Clubs, led to the famous Supreme Court decision exempting Organized Baseball from provisions of the Sherman Antitrust Act.) As the most powerful man in baseball, Johnson’s comments received wide publicity, probably what he intended.

Barrow at the time was in the midst of trying to organize his clubs for the upcoming 1917 season. He did not want any distracting rumors of impending major- league status for select teams. Barrow called the idea of a third major league “preposterous” and stated that the International League would operate in 1917 as a class AA league. He did squeeze in the caveat, however, that a third major league would come about only as a last resort in the event of a disastrous 1917.

As the 1917 season was getting underway, the country was mobilizing for World War I, and Barrow feared for his league’s profitability. By July a couple of International League teams were considering disbanding after the season, and the economic outlook appeared bleak enough to warrant more thought about Barrow’s caveat. As the league struggled financially, some sentiment to cut Barrow’s salary began to develop. In the midst of this renewed turmoil, Barrow again received the tacit approval of Johnson and the National Commission for a third major league. This time he also enlisted several American Association franchises. The Union League, as it was named, would consist of four International League franchises (Baltimore, Buffalo, Toronto, and probably Newark) and four from the American Association (Indianapolis, Louisville, Toledo, and possibly Columbus), with Barrow as president.

The politics of the proposed Union League were complex. The major leagues supported its creation as a way of helping the minors survive without requiring active financial support from the majors. Adding to its appeal was that several reports suggested that, as a compromise to settle the lawsuit, the Baltimore franchise in the new league would go to the Baltimore owners of the old Federal League franchise. Many major- league owners did not envision the Union League as a true third major but, at least initially, as a step below. For example, the new league would likely be exempt from the major league–minor league draft but would not have a member on the National Commission. Johnson also viewed it mainly as an act of war- time expediency. The plan contemplated that those International League and American Association franchises not included in the Union League would join lower-classification minor leagues in their geographic area. This would displace some teams in those leagues. In turn, the displaced teams would need to be relocated, creating a domino effect on the lower minor leagues. And so the Union League would require territorial restructuring of the minor leagues as a whole.

Struggling financially themselves, the lower minor leagues had no interest in significantly disrupting their operations by reorganizing along the lines Barrow suggested. At the higher end, American Association president Thomas Hickey and the four leftover franchises in the two merging leagues had no desire to see their dissolution. At the National Association meetings in mid-November the minor leagues decisively voted down the restructuring proposal 11–2, effectively ending Barrow’s hopes for the Union League.

Straightforward and blunt as always, Barrow, to his misfortune, had not learned his lesson from the failed at- tempt at a third major league in 1914. Again, his strength of will combined with passive support from the National Commission were not enough to persuade the baseball establishment to agree to a considerable restructuring. Barrow again demonstrated his blindness to the need for the behind-the-scenes politicking that such a substantial project demanded.

Not surprisingly, discussion of the creation of the Union League created a rift between the proposed participants and those who would have been excluded. With this festering distrust among the franchise owners and the survival of their league in doubt, their mood had grown hostile, gloomy, and pessimistic. At the league meeting on December 10, 1917, Barrow took the offensive. He declared Joseph Lannin’s Buffalo franchise, which owed roughly $18,000, including player’s salaries, league fees, and guarantees to visiting clubs, forfeited to the league.

With Lannin neutered, the owners addressed two issues: whether to suspend operations for 1918, and Barrow’s future as league president. In a sign of the league’s distress, the former failed narrowly, by a 4–3 vote; Rochester, Richmond, and Providence voted to put the league on ice for a year. As to the latter, Barrow had underestimated the lingering resentment generated by his failed attempt to establish the Union League. The four franchises not included in the Union League allied with Dunn to force Barrow’s resignation. (Dunn believed—probably correctly—that the Union League would have squeezed him out for the Federal League owners in Baltimore.)

Ultimately, the offended owners voted 4–3 to reduce Barrow’s salary from $7,500 to $2,500, an insult they correctly perceived would induce Barrow to resign. At the end of the meeting Barrow and Lannin nearly came to blows. Barrow’s two staunchest supporters, Toronto’s McCaffery and Newark’s Jim Price, held Barrow back, telling him, “Don’t hit him, Ed, he’s got a bad heart.” Now effectively out of a job, Barrow remained bitter. He later grumbled that, if the league chose to degenerate to the level of a Class B league, he was happy to be no party to it.

DAN LEVITT is author of “Ed Barrow: The Bulldog Who Built the Yankees’ First Dynasty” (Nebraska, 2008) and coauthor, with Mark Armour, of “Paths to Glory: How Great Baseball Teams Got That Way” (Brassey’s, 2003), which won the Sporting News–SABR Baseball Research Award.

Sources

Newspapers

Atlanta Constitution

Boston Globe

Chicago Tribune

Los Angeles Times

New York Times

The Sporting News

Toronto Star

Washington Post

Books and Articles

Alexander, Charles C. Our Game: An American Baseball History. Holt, 1995.

Barrow, Edward Grant, as told to Arthur Mann. “Baseball Cavalcade.” Saturday Evening Post, 24 April 1937.

Barrow, Edward Grant, with James M. Kahn. “My Baseball Story.” Parts 1–6. Colliers, 10 May, 27 May, 3 June, 10 June, 17 June, 24 June 1950.

———. My Fifty Years in Baseball. Coward-McCann, 1951. Bradley, Hugh. “The Ed Barrow Story.” Parts 1–4. New York Journal American, December 1953.

Burk, Robert F. Never Just a Game: Players, Owners, and American Baseball to 1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

Daniel, Dan. “From Peanuts to Pennants: The Story of Ed Barrow.” Parts 1–11. New York World Telegram, January–February 1938.

Foster, John B., ed. A History of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues, 1902–1926. National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues. N.d.

Fullerton, Hugh S. “Baseball—The Business and the Sport.” The American Review of Reviews, April 1920.

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, eds. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball. 3d ed. Baseball America, 2007.

Levitt, Daniel R. Ed Barrow: The Bulldog Who Built the Yankees’ First Dynasty. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008.

Murdock, Eugene C. Ban Johnson: Czar of Baseball. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1982.

Okkonen, Marc. The Federal League of 1914–1915: Baseball’s Third Major League. Garrett Park, Md.: Society for American Baseball Research, 1989.

Okrent, Daniel, and Harris Lewine, eds. The Ultimate Baseball Book. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1988.

Reach Official American League Base Ball Guide. A. J. Reach, 1915–18.

Seymour, Harold. Baseball: The Golden Age. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide. American Sports Publishing Company, 1915–18.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970. Bicentennial Edition. 1975.

U.S. House of Representatives. Hearings before the Subcom- mittee on the Study of Monopoly Power of the Committee of the Judiciary: Organized Baseball (82d Cong., 1st sess., 1952).

U.S. House of Representatives. Report of the Subcommittee on the Study of Monopoly Power of the Committee of the Judiciary: Organized Baseball (82d Cong., 2d sess., 1952).

Voigt, David Q. American Baseball Volume 1: From Gentle- man’s Sport to the Commissioner System. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1983.

Wright, Marshall D. The American Association. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 1997.

———. The International League: Year-by-Year Statistics, 1884–1953. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 1998.

Other Sources

Correspondence between Ed Barrow and minor-league team executives, 1917.