Editor’s Note: Fall 2020 Baseball Research Journal

This article was written by Cecilia Tan

This article was published in Fall 2020 Baseball Research Journal

Historians, start your engines! The events of the year 2020 cry out for documentation. While living through it, some of us may have struggled to make sense of it all, but perhaps in hindsight it will become clear. If the accounts we leave behind are accurate, a hundred years from now folks like us will look back and be able to understand the otherwise surreal-seeming snapshots that will be archived from this past month alone: the people sitting at restaurant tables next to parking meters, the surgical masks around the necks of the World Series champions during their on-field celebration, the presidential legal team setting up a podium in a landscaper’s parking lot.

Historians, start your engines! The events of the year 2020 cry out for documentation. While living through it, some of us may have struggled to make sense of it all, but perhaps in hindsight it will become clear. If the accounts we leave behind are accurate, a hundred years from now folks like us will look back and be able to understand the otherwise surreal-seeming snapshots that will be archived from this past month alone: the people sitting at restaurant tables next to parking meters, the surgical masks around the necks of the World Series champions during their on-field celebration, the presidential legal team setting up a podium in a landscaper’s parking lot.

Write it down. Take screencaps. Photograph it. Make clippings from the newspapers. Archive PDFs. You may think we have such a plethora of information sources these days that these steps are hardly necessary. But look how much about the 1918 pandemic was forgotten, despite that being the heyday of American newspapers, when many Americans read several a day and every city had numerous papers competing.

And there will be many who will want to “forget” the strain and darkness of baseball in 2020—what I’ve been calling The Irregular Season. The truncated spring training, the bitter labor tussle between owners and players that resulted in a mere 60-game season, the outbreaks of COVID-19 among Miami Marlins and then other teams—with Justin Turner of the Dodgers even receiving a positive test result during the clinching game of the World Series. Teams and MLB were forced to improvise, with rules and procedures, and even schedules and travel itineraries, changing on the fly. Alternate sites, taxi squads, the Blue Jays playing in upstate New York, broadcasters working from their home parks while the teams were away, the press scrum happening via Zoom, The Irregular Season really happened. Maybe the super-short season was a blessing, sandwiched between the spring and winter COVID-19 infection surges. Hindsight will tell. Write it all down now because piecing it together later is going to be a bear.

We’re going to be analyzing the effects of 2020 for years to come. How many players will find their careers affected by it? The minor leagues were shut down and so were (most) college sports. The major leagues saw an off-the-charts number of players sidelined with injuries. Some big leaguers opted out of playing entirely; a few decided to have surgery during the interregnum. I expect many SABR members out there, as well as decision-makers in front offices around the league, are already starting to analyze and predict the effects.

Baseball’s economics have been affected, too. Large numbers of front-office employees have been laid off in the wake of the lost 2020 revenue. This will surely reverberate through the upcoming negotiation of the Collective Bargaining Agreement. What changes might be wrought in the way teams do things or the way the league operates, born in reaction to 2020 but having repercussions for decades? The article that anchors this issue of the journal, appearing last, is Richard Hershberger’s account of the “First Baseball War,” in which the nineteenth-century clash between leagues contributed to the creation of the reserve system that suppressed free agency until the late twentieth.

In 2020 we also saw massive, nationwide protests against police brutality and racial injustice, and we saw baseball players and the league itself take unprecedented steps to acknowledge racial injustice in the United States. The commissioner’s office already has a department that has been actively addressing issues relating to diversity and inclusion in ways that would have been unheard of even two decades ago. Will the pandemic-driven layoffs from front offices hurt the initiatives toward more hiring of women and underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities that the league has been promoting? (Probably.) But 2020 also gave us two other unprecedented firsts: Kim Ng has been hired as the first woman general manager of an MLB team as well as the first Asian American GM, and Alyssa Nakken is the first woman in uniform to take the field as part of the coaching staff of a major league team, the San Francisco Giants. She is joined by a bevy of women coaching and instructing in the minors—Rachel Balkovec for the Yankees, Rachel Folden for the Cubs, Christina Whitlock for the Cardinals… except that in 2020 there were no minor league seasons.

History is always being made; that is SABR’s stock in trade. But in a watershed year, the changes come fast and thick. I haven’t even mentioned the fact that during the year 2020 the minor leagues as we knew them didn’t merely miss this season: they ceased to exist. On September 30, the agreement between MLB and the affiliated minor leagues expired, and MLB has unilaterally imposed control, eliminating 40 of 160 teams with one fell swoop. At the same time, MLB has been courting partnerships with the independent leagues, using the Atlantic League in 2019 as a testing ground for rules changes that were put into practice in MLB in 2020.

And I haven’t even mentioned all the rules changes! Are 2020’s universal DH and extra-innings procedures a harbinger of things to come? But this introduction is already twice as long as usual. To sum up: we’re going to be writing about, talking about, and researching 2020 for a very long time, and not “just” about baseball. Every one of these changes in baseball can be tied to a parallel in American life or society, from adapting to the pandemic to advances for women’s equality, from the fight for racial justice to the fight for raising the minimum wage. Even the consolidation of control of the minor leagues is in line with late- stage capitalist corporate practices, including vertical integration and end-to-end lifecycle production. The World Series may have been played in a “bubble” but baseball doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

Which isn’t to say that one can’t write about “just” baseball. Plenty of articles in this issue are compelling and intriguing without invoking geopolitics. I would be captivated by Theo Tobel’s breakdown of brushback pitches even without knowing that he is a high-school student taking part in remote learning due to the pandemic. Randy Robbins noticed a statistical quirk in the record of Warren Spahn and it prompted an examination of one of the game’s pitching greats. Will Melville and Brinley Zabriskie undertake the task of trying to determine how much benefit, if any, the 2017 Astros derived from their cheating efforts, while Irwin Nahinsky analyzes the effects of luck and skill on team success.

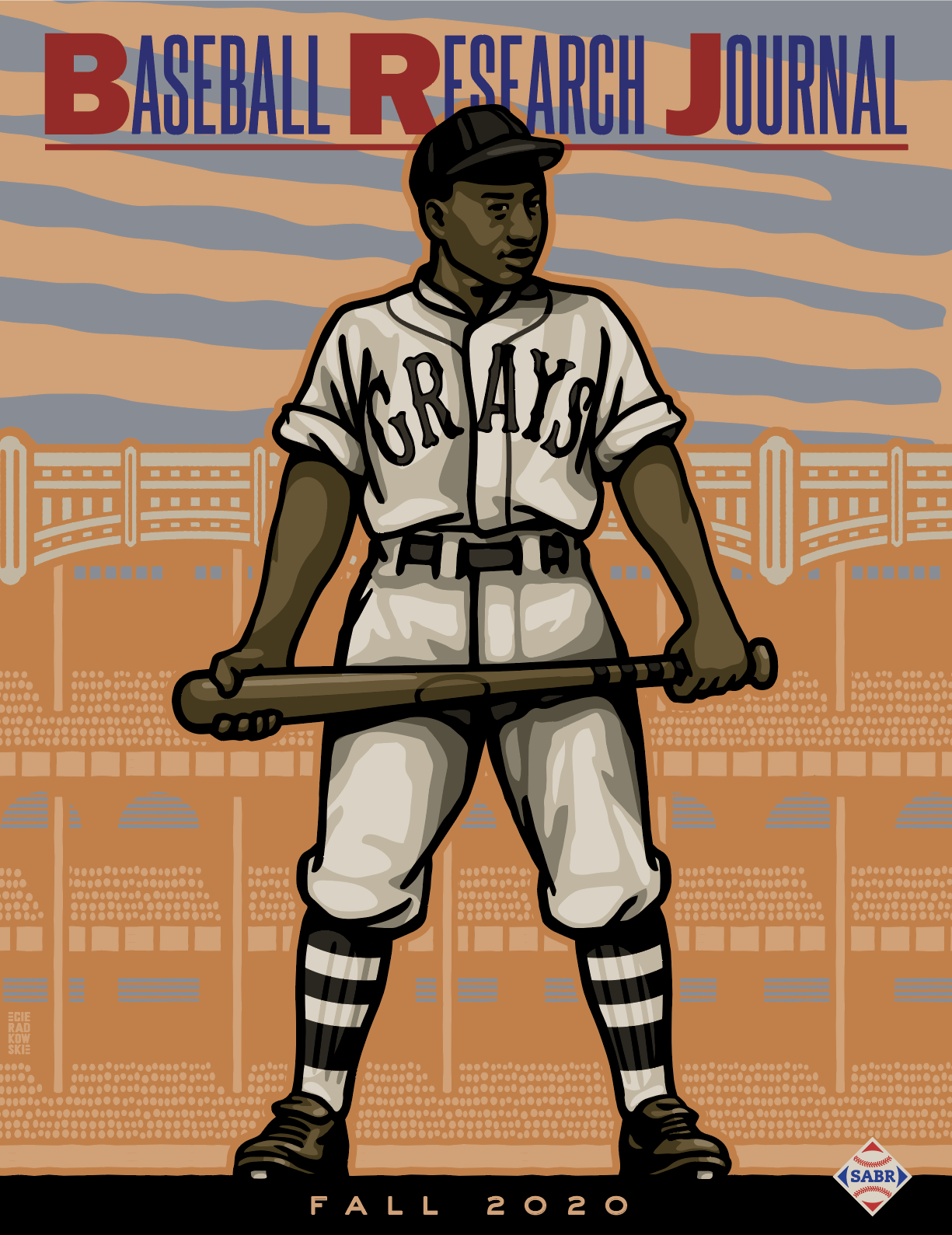

But so many pieces of baseball history and analysis can’t help but be tied to a bigger world, and I find many of them to be bittersweet this time around: Ron Backer looks at Lou Gehrig in a new light—klieg lights, in fact—in his article on Gehrig’s Hollywood career, which like his life and playing career was cut short by ALS. Mary Hums and her team document MLB’s decision to change the name of the “disabled list” to “injured list,” including the advocacy and rationale behind the change, and an analysis of fan reactions to it. Charlie Pavitt delves into the fact that a player’s ethnicity can be a predictor for what position he plays in MLB. Howard M. Wasserman examines Jewish players through the lens of their performances on Yom Kippur, while Alan Cohen examines one of the great hitters of all time, Josh Gibson. Because of racial segregation, Gibson never had the opportunity to play in the major leagues, but because many Negro League teams did play games in major league ballparks, we can look at those performances to prove how prodigious he truly was.

I don’t know what the 2021 season holds in store. Whether the season starts on time, or happens at all, may depend on medical science (vaccines) and on geopolitical and logistical issues (how quickly vaccine doses can be distributed to the populace). I just know that as I write this, 2020 isn’t quite over yet, and we won’t be “closing the book” on it for a long time.

— Cecilia M. Tan

SABR Publications Director

- Buy the magazine: Click here to purchase the print edition of the Fall 2020 Baseball Research Journal from Amazon.com.

- Download the e-book edition: Click here to download the PDF version of the Fall 2020 Baseball Research Journal.