Everybody’s a Star: The Dodgers Go Hollywood

This article was written by Jeff Katz

This article was published in The National Pastime: Endless Seasons: Baseball in Southern California (2011)

In a scene from the Marx Brothers’ “Animal Crackers”, Chico and Harpo attempt to switch a priceless painting with a copy. After the usual mayhem, the duo turns to exit, stage left. When they open the French doors, there’s a caterwauling of thunder, with lightning and sheets of rain. The pair close the doors, head toward the opposite side of the room, and open the portals. Outside the birds are twittering; it’s beautiful and sunny.

“Ha, ha, California!” exclaims Chico joyfully.[fn]Marx, Chico. Animal Crackers. Directed by Victor Heerman. Los Angeles: Paramount Pictures, 1930. [/fn]

Prior to the 1958 season, the Dodgers took a similar journey west, leaving the grime and decay of Brooklyn for the balmier environs of Southern California. Happily ensconced under the sun, they were quickly embraced not only by fans starved for major league baseball but also by the entertainment world. The motion picture industry had been centered in Hollywood for decades, and the burgeoning television industry had recently switched coasts, leaving the advertising-centric world of New York City for the glamour and studio life of Los Angeles.

After the Dodgers’ arrival, a marriage was made. Stars and starlets became a staple at Dodgers home games, and ballplayers were eagerly sought to appear in television episodes and movies. The late 1950s was an innocent time of simple athletic hero worship; a Dodger star on screen was sure to attract a bigger audience.

After the Dodgers’ arrival, a marriage was made. Stars and starlets became a staple at Dodgers home games, and ballplayers were eagerly sought to appear in television episodes and movies. The late 1950s was an innocent time of simple athletic hero worship; a Dodger star on screen was sure to attract a bigger audience.

Jerry Lewis’s The Geisha Boy (1958) marks the first credited appearance of the new Los Angeles Dodgers. Film’s greatest idiot, Lewis had a soft spot for baseball dating to his youth, when his hero was the New York Giants’ future Hall of Famer, first baseman Bill Terry. In this film, Jerry carries on as the quintessential fan, yelling and mugging as he watches the Dodgers visit a Japanese team. Lewis would turn to the Dodgers often, featuring coach Leo Durocher in The Errand Boy (1961) and casting speedy centerfielder Willie Davis in a major part in Which Way to the Front? (1970), with Davis, in army togs adorned with an incongruous peace symbol, playing a member of Lewis’s private army.

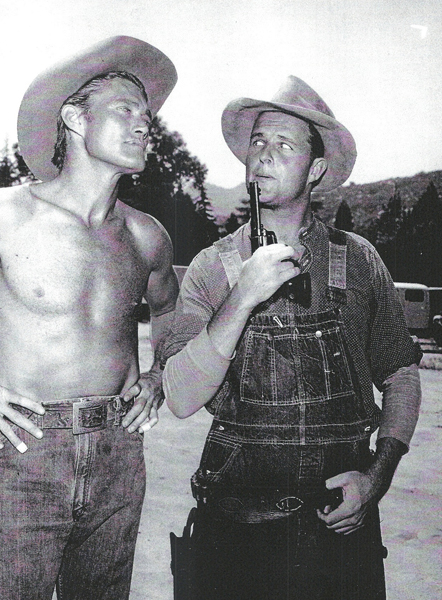

Much to the chagrin of Brooklyn fans who had waited decades for their first World Series victory in 1955, the Los Angeles Bums won it all in their second season. After defeating the Chicago White Sox in the 1959 World Series, many on the team were offered TV roles. Duke Snider menacingly rode into town on The Rifleman. Wally Moon, after a season in which he turned the Dodgers’ homer-friendly Coliseum into a launching pad for his “Moon shots,” brought his dark looks and heavy eyebrows to perfect use as a Western hero in an episode of Wagon Train. Another fall star, outfielder Chuck Essegian, appeared in yet another oater, Sugarfoot. And, of course, there were Koufax and Drysdale.

MARQUEE STARS

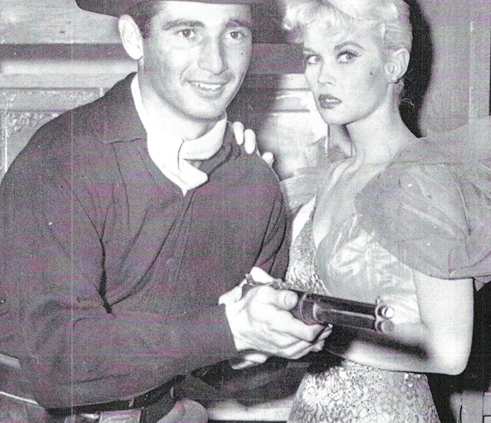

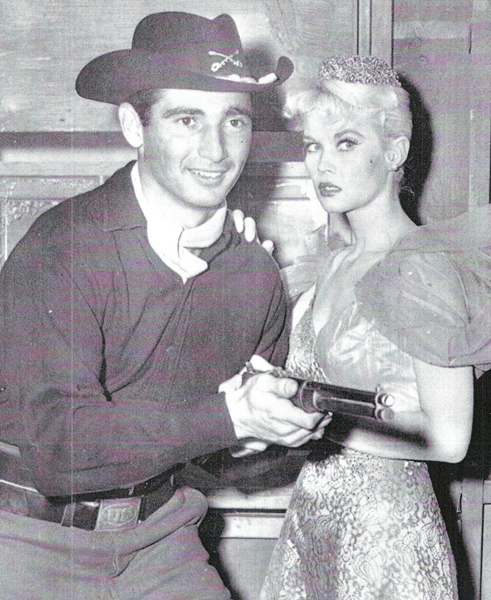

As if divine talent weren’t enough, Sandy Koufax had the looks of a matinee idol: dark, slender and Jewish, more Robert Taylor than Robert Redford. Hollywood came calling after Sandy gave a sneak preview of his future brilliance in the 1959 World Series. Koufax appeared in three television programs in 11 days. He first played a policeman in “Ten Cents a Death,” on the trailblazing series 77 Sunset Strip (January 29, 1960). Two days later, amid much press coverage, Sandy appeared in an episode entitled “Impasse” on Colt .45. (Koufax dies in the opening scene, before critics could get a handle on his acting chops. Pleased that he didn’t “have to ride a horse, just die,” the quick-witted Koufax remarked, “I’ve gone out quicker in some games.”[fn]Finnegan, Joe. “Pitcher Koufax, Hit in Acting Debut, Relieved After first inning Collapse.” National Baseball Hall of Fame Library. [/fn]) He then returned as a doorman in the detective series Bourbon Street Beat.

Hollywood couldn’t get enough of California native Don Drysdale. Tall, handsome, and the ace of the pitching staff—at least until Koufax hit his stride—“Big D” showed up on the small screen in an episode entitled “The Hardcase,” (January 31, 1960) on The Lawman. A Western was the natural beginning to the acting career of Drysdale, who had been described as “a handsome giant in the John Wayne tradition.”[fn]“The Drysdales in Showbiz.” Los Angeles Herald Examiner, 25 March 1966, D2. National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.[/fn] He followed up that year with another character role, that of Eddie Cano in an installment (“Millionaire Larry Maxwell”) of The Millionaire.

As the decade progressed, the team became more Californian, their Brooklyn ancestry more remote. On the field, the Dodgers were the class of the National League, winning two more world championships (1963 and 1965) and garnering two second-place finishes before record numbers of devoted fans. They were truly hometown Los Angeles, and the appearance on the screen of their stars was losing its novelty. Only the most telegenic and famous Dodgers would continue to get the call from Tinseltown.

As the decade progressed, the team became more Californian, their Brooklyn ancestry more remote. On the field, the Dodgers were the class of the National League, winning two more world championships (1963 and 1965) and garnering two second-place finishes before record numbers of devoted fans. They were truly hometown Los Angeles, and the appearance on the screen of their stars was losing its novelty. Only the most telegenic and famous Dodgers would continue to get the call from Tinseltown.

Coach Leo Durocher brought west his own show business resume, a failed marriage to movie star Laraine Day and friendships with screen stars Spencer Tracy and George Raft. “The Lip,” famous in baseball since his playing days in the 1920s, was cast as himself in the aforementioned The Errand Boy and in memorable TV segments of The Beverly Hillbillies, The Munsters, and Mister Ed (this last rated by TV Guide as the 73rd best episode in television history). Besides Durocher, Koufax and Drysdale were the two most often solicited by Hollywood to boost a show’s profile.

However, the most fascinating appearance on television during the first half of the 1960s is that of Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley in a parable of the Brooklyn Dodgers story for a 1965 episode of Chuck Connors’s Branded. In “The Bar Sinister,” with O’Malley cast as a crusty doctor, the town mayor is willing to rip a beloved boy (read Dodgers) from his rightful guardian, his Native American mother (read Brooklyn). Why? To acquire land and riches, an allusion to the controversial transfer of Chavez Ravine and its environs by the City of Los Angeles that enticed O’Malley westward—parallels that made Walter O’Malley the perfect choice for the role.

THE STUDIO VERSUS THE BALLPARK

O’Malley was not the only Dodger to arrive in film land thanks to Chuck Connors. Connors, an ex-Brooklyn first baseman, had become a television star with The Rifleman, Branded, and the short-lived Cowboy in Africa. Through his starring vehicles, several Dodgers—Roy Gleason, Ron Perranoski, Duke Snider, and Don Drysdale—got their TV breaks, but the former first sacker’s biggest role came in the most important Dodger story of the mid-1960s, the Great Holdout. This significant convergence of baseball and show business took place after the Dodgers’ 1965 world championship as both industries competed for the services of the two marquee stars, Koufax and Drysdale, who had notched a combined 49 wins that season. While stars like Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle had reached the lofty standard of $100,000 in salary, no pitcher had been able to attain that plateau. In late October, at their first meeting with Dodgers general manager Buzzie Bavasi, the two hurlers presented a seven-figure proposal they would split down the middle over the next three years. Bavasi laughed and offered Koufax $100,000 for 1966 and Drysdale $90,000. The pitchers had formed a players union of two; one would not sign without the other. They turned him down.

Advising the Dodgers duo was agent/attorney Bill Hayes of Executive Business Management in Beverly Hills. In February 1966, as spring training began, Hayes announced that Drysdale and Koufax would have speaking roles in Warning Shot, a new film starring David Janssen. With Koufax playing a detective sergeant and Drysdale a television commentator, production was to start on April 4, eight days before the defending champs were to play their home opener. Said Director Buzz Kulik, envisioning sports page headlines translating into boffo box office receipts, “They’re hot properties.”[fn]Mitchell, Jerry. Sandy Koufax. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1966, 189. [/fn]

Said Bavasi, “Good luck in the movies, boys!”[fn]Gruver, Edward. Koufax. Dallas: Taylor Publishing Company, 2000, 200. [/fn]

Dodgers teammates and fans grew more concerned as publicity stills for Warning Shot began circulating. Riding in to save the day was Chuck Connors, who knew two things: Bavasi had quietly arrived back in California from Florida, and Koufax and Drysdale were itching to get back on the mound. Towards the end of March, Connors called Bavasi and said, “These fellas are ready to sign.”[fn]Ibid. [/fn] He then called Drysdale and told him he should give the Dodgers GM a ring. A meeting was arranged at Nicola’s, a restaurant near Dodger Stadium, and terms were hammered out, Drysdale acting with Koufax’s blessing. The holdout was over: Koufax signed for one year at $125,000, Drysdale for one year at $110,000.

As the 1960s wore on, the wholesome appeal of a Dodger in uniform lost its luster. And by the post-Ball Fourera of the 1970s, as ballplayers were transformed in the public eye into money-hungry, drug-using, sex-driven, self-absorbed divas, the appearance of a pampered superstar could turn off as many people as it could turn on. Once reporters had covered up the personality quirks and foibles of the average athlete; now their mission was to expose their every gaffe and misdeed. The day when viewers welcomed two-dimensional sports figures into their living rooms as the kind of men their sons could safely revere and their daughters could pine over without threat was over.

Today, as fans deal with loving the game of baseball while remaining ambivalent about its players, it’s unlikely that TV shows and movies will ever return to the days when Gil Hodges looks on in wonder as Jerry Lewis takes a pitch to the mouth, Sandy Koufax pitches to a grocery store owner on a sandlot, or Don Drysdale chats with The Beaver on a long distance call. Perhaps this is why the Dodgers-Hollywood connection and the players’ performances of the 1950s and early 1960s resonate with the sweetness of that time. A refreshing lack of cynicism and self-awareness make this a wonderful time to revisit. It was an era when we could still look forward to seeing our athletes as supermen without the character failings that we mortals suffer through. And isn’t that what Hollywood dreams are made of?

JEFF KATZ loves baseball so much that he and his family moved to Cooperstown in 2003, just to be close to the Hall of Fame. Since then, Jeff’s work has been published in the anthology “Play It Again” (McFarland, 2006) and his own “The Kansas City A’s & The Wrong Half of The Yankees” (Maple Street Press, 2007), the latter receiving national attention. More recently, Jeff has turned to his other love, rock & roll, with his inventive blog “Maybe Baby (or, You Know That It Would Be Untrue)”.