Exit Stage Left: The Sad Farewell of Cap Anson

This article was written by Michael Haupert

This article was published in The National Pastime: Heart of the Midwest (2023)

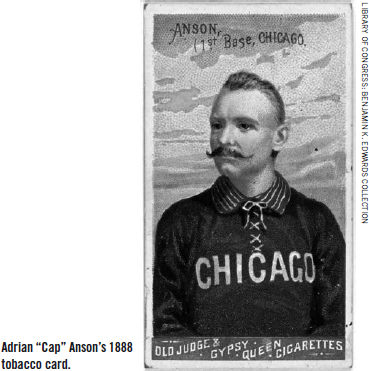

Adrian “Cap” Anson was one of a handful of players whom William Hulbert pilfered from eastern clubs before the 1876 season.1 In a storied White Stockings career, Anson managed the team for 19 years, capturing five titles, becoming the first member of the 3,000 hit club, being elected to the Hall of Fame in 1939, and even becoming part owner of the White Stockings. But there is one goal he did not achieve, and it ultimately led to his exit from the team on terms very different than his career should have dictated. In turn, that exit led Anson to an ending hardly becoming of the man the Chicago Tribune once called “the most conspicuous ballplayer in the nation.”2

IN THE BEGINNING

Adrian Constantine Anson was born in Marshall (present-day Marshalltown), Iowa, on April 17, 1852. By his own admission, he was a lackluster student, but when it came to baseball, he practiced diligently until he mastered the game. At age 15 he earned a spot on the town team. At age 19 he signed his first professional contract with Rockford in the National Association for the princely sum of $66.66 per month.3

Rockford lasted only one season, but Anson outlasted the organization. He starred for the Athletics for the next four years, and then jumped from the National Association to the National League’s Chicago White Stockings, where he would remain for the final 22 seasons of his career.

Albert Spalding retired from his managerial and playing duties after the 1877 season, and took over the presidency of the Chicago White Stockings. He named Anson manager for the 1879 season. There he remained, as “Cap” for the rest of his career.

Anson opened the 1880 season with another title to add to his player-manager status: stockholder. On April 1, he purchased five shares of the team.4 This ownership of stock was credited as a powerful influence in keeping him from absconding to the Players’ League a decade later.5

The Players’ League was formed in 1890, competing head-to-head with the National League in seven of eight NL cities. By this time Anson was a 20-year veteran and had been a part-owner for half of that time. As such, he was not going to bolt to a new league, but he was severely critical of those who did. With Spalding working behind the scenes, Anson served as a foghorn, blasting the “traitors” who jumped to the new league. The PL lasted only one season, but the enmity Anson sowed amongst the players who returned lingered on.

While Anson was hailed in the press as “the man who saved the National League,” he was not viewed so gallantly by his former teammates. Stars Hugh Duffy and George Van Haltren refused to return to Chicago, crippling the White Stockings during the 1891 season. In September the White Stockings held first place, but a late-season surge by Boston gave them the flag. Anson blamed his detractors from the PL for easing up when they played Boston, allowing them to overtake his club down the stretch.6

In April 1891, after an exhausting but successful battle to defeat the PL, Albert Spalding resigned his club presidency in order to devote more time to his sporting goods business. He recommended club secretary James Hart for the position, who was unanimously elected by the board. He retained stock in the ballclub, and expressed his confidence in Hart, “a man thoroughly competent and well qualified.”7

The transition was not a smooth one. Anson was not happy to have been passed over for the presidency. Despite conciliatory words from Spalding, who assured him that Hart was merely a figurehead, the incident opened a rift between Spalding and Anson.8 Anson also had problems with Hart, and the two began to butt heads almost immediately. “Hart regarded Anson as a relic of the past who was unwilling to change with the times. Anson countered by calling Hart a usurper who undermined his authority by encouraging rebellion among the players.”9

In the fall of 1892 Spalding and Hart reorganized the club as part of a sale that would eventually result in Hart owning a majority of the shares. The new corporation was chartered by Hart and two associates, but the original stockholders had the opportunity to buy into the new corporation. Spalding and Anson took advantage of the opportunity, and Anson stayed on as field manager. Anson signed a new contract with the newly formed corporation, but it was for one year less than the ten-year pact he had signed three years earlier. Anson would later claim that he was unaware of this detail, and it would prove to be a costly oversight on his part.

The performance of the team fell off dramatically after Hart became president. Over the final six seasons of his tenure with the club, Anson’s Colts, as the press dubbed them, experienced four losing seasons, and never finished higher than fourth place. During his first 13 seasons at the helm, Anson had never experienced a losing season, compiling a .632 winning average and claiming five pennants. Anson publicly blamed Hart for the team’s struggles on the field, complaining that he was miserly and refused to obtain good players because he didn’t want to pay the salaries they would command.

1897 was a dismal season for Anson and the White Stockings. The team plunged to ninth place, 34 games out of first. Only once before during Anson’s tenure had they fallen so low and finished so far behind. Their .447 winning average was the third lowest in Anson’s 19 years at the helm. Anson’s on-field performance also fell short of his career standards. His RBI total fell for the third straight year, and his batting and slugging averages were below the league average. At 45, he was the oldest player in the league by five years, and it was starting to show.

The decision of whether or not to retire was not left up to Anson. His long-term contract expired in January of 1898 (one year earlier than originally negotiated) and Hart did not renew it, almost certainly with the blessing of Spalding (even though, as president, Hart did not need Spalding’s approval). The following month, perhaps as a consolation after his dismissal, Spalding offered Anson a 60-day window to purchase controlling interest in the team. But by the April 15 deadline, Anson did not have the money and the deal fell through. An incensed Anson accused Spalding of duplicity, charging, “there was never any intention on the part of A.G. Spalding and his confréres to let me get possession of the club.”10 Anson was probably right, in that Spalding certainly realized he was highly unlikely to be able to come up with that kind of cash in such a short period of time.

Hart explained that the decision to let Anson go was made by the stockholders, who felt the fans desired a change of management. He praised Anson’s long and faithful service to the club, wishing him the best in his future endeavors. “There is not now, and never has been, friction between Captain Anson and myself.”11 Both parties belied this lack of friction in a contentious exchange of letters published in the Chicago Tribune later that year.

Seeking to defend his motives, Hart explained Anson’s financial connections to the White Stockings. His contract called for a fixed salary plus a percentage of net profits each year. According to Hart there were no profits in any year from 1890-93. Nevertheless, in two of those years Anson was paid a sum “nearly double that called for in his contract.” And in a third a debt to the club in the amount of $2,600 for previously purchased shares of stock was forgiven. In 1897, Anson once again took an advance from the club, this time in the amount of $2,400, “which at the present time stands charged to him on the books of the club, and it has never been paid.”12

Anson rebutted, claiming that Hart overstated losses and denied, “emphatically that I owe the club $2,400…I worked for the club for a period of time extending over twenty-two years, my contract calling for a stated salary and 10 per cent of the net profits…but I have never been allowed to see [the books], and whether I have had all that was coming to me or not is an open question in my mind.”13

The end of the Anson era in Chicago was bitter and ugly, hardly becoming the career of a legend. After 27 seasons, Cap Anson’s playing career was over. He retired as baseball’s winningest manager, and its all-time leader in games played, at-bats, runs, RBIs, doubles, and hits. He was the first member of the 3,000 hit club, and its only member until 1914. The Chicago Tribune estimated that since he began playing ball as a teenager in Marshalltown, Iowa, he had piled up more than 7,000 hits.14 There would be no more.

Spalding planned a testimonial dinner for Anson, raising $50,000 for a tribute to the long-time star. “It seems a pity,” said Spalding, “that a man like Anson should be allowed to drop from sight without the people being given a chance to show their high esteem of him.”15

Anson refused the honor, saying “I don’t know as I am yet ready to say that I am out of baseball. I am neither a pauper nor a rich man, and prefer to decline. The public owes me nothing…the kind offer to raise a large public subscription for me…is an honor and compliment I duly appreciate… At this hour I deem it both unwise and inexpedient to accept the generosity so considerately offered.”16

Anson retired as a player, but returned to the bench in 1898, replacing Bill Joyce as manager of the New York Giants. He lasted only as many games as years he spent in Chicago. After going 9-13, he was fired, and Joyce was reinstated. It was his last official association with major-league baseball, though not due to lack of effort.

After his exit from the Giants, Anson tried to obtain a Western League franchise and move it to the South Side of Chicago, but Spalding, whose approval for the move was necessary under rules of the National Agreement, refused permission. For a third time, Spalding spiked his former teammate’s desire to move into the front office of a professional ballclub. Later, Anson served as president of an ill-fated revival of the American Association, which attempted to play in 1900, but folded due to financial pressures.17

BEYOND BASEBALL

In the summer of 1901 rumors abounded that Cap Anson was on the verge of making a comeback in Chicago by purchasing his old team.18 But the rumors proved unfounded. Instead, it was his nemesis, Jim Hart, who took over majority control.

Cap Anson was finished with baseball. He lived out the final two decades of his life in the entertainment industry, but not as a ballplayer. Anson opened a bowling and billiards parlor in downtown Chicago in 1899. He served as a vice-president of the new American Bowling Congress. He then turned to politics, serving one term as Chicago city clerk. In late 1905 Anson sold his stock in the Chicago ballclub and expanded his business.

He invested the remaining funds from his stock sale in semipro ball, purchasing a team (called Anson’s Colts) and constructing his own ballpark. He even occasionally donned a uniform and took the field, but the Colts never achieved more than mediocrity and Anson sold the team after three years.19

This was the latest in a string of failures for Anson. He had mortgaged his home to buoy his business ventures, and he lost it, leaving him penniless, homeless, and unemployed. He and his wife, Virginia, moved in with their daughter. In 1916, after a long illness, Virginia died. Though broke, Anson was still wildly popular in Chicago and his reputation as a ballplaying legend extended across the country. He thus began the final chapter of his career by hitting the boards and travelling the vaudeville circuits. Though he eventually reached the big time, he did not grow rich.20

In January 1922, Anson was hired to manage the new Dixmoor Golf Club, set to open later that year. He actively promoted the club and took enthusiastically to his new calling. But it did not last long. While taking a walk near his home, he collapsed and was rushed to the hospital, where he died a few days later, on April 15, 1922, just two days shy of his 70th birthday.

His death was front page news. The Chicago Tribune lauded him as an honest, temperate, and dignified gentleman as well as a model husband and ballplayer.21 Hugh Fullerton gushed that Anson was, “the greatest man in the history of baseball…what Ruth is to baseball today is but a small comparison to what Capt. Anson was when he led his White Stockings onto the field.”22

The baseball fraternity mourned Anson. His funeral was attended by hundreds, ranging from baseball fans to political and business dignitaries. The overflow crowd spilled onto Michigan Avenue, snarling traffic. The White Sox game that day was delayed until late afternoon to allow time for the players of both teams to attend the funeral, where Judge Landis delivered the eulogy.23

Anson did not leave an estate, and the National League paid for his hospital and funeral expenses. They also arranged to have his wife’s remains relocated from Philadelphia to lie alongside Anson in Chicago, and erected a tombstone at his gravesite. On it was inscribed the simple but certain epitaph, “He played the game.”24

MICHAEL HAUPERT is Professor of Economics at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. His teaching and research interests include economic history and the economics of the sports industry. He has written three books, and more than 100 articles on the business of baseball. He has been co-chair of SABR’s Business of Baseball committee and editor of the committee newsletter “Outside the Lines” since 2012. He received the Doug Pappas Award in 2014 and the Alexander Cartwright Award in 2020.

Notes

1. For a full discussion of Hulbert’s machinations, see Michael Haupert, “William Hulbert,” SABR BioProject, and Michael Haupert, “Chicago Cubs Team Ownership History, 1876-1919,” SABR BioProject.

2. “Capt. Anson, Baseball Hero, Dies at 70,” Chicago Tribune, April 15, 1922, 1.

3. Thorn, John, “Anson’s First Baseball Contract,” May 1, 2019, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/ansons-firstbaseball-contract-4c73bdb3ddef.

4. Cash Book 1876-1881, Chicago Cubs Collection, 223-24.

5. Harold Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 1960), 330, 331.

6. David Fleitz, “Cap Anson,” SABR bio project https://6sabr.org/bioproj/person/cap-anson.

7. “Hart is President Now,” Chicago Tribune, April 15, 1891, 5.

8. “Anson Replies to Hart,” Chicago Tribune, January 7, 1900, 17.

9. Art Ahrens, “Chicago Cubs: Sic Transit Gloria Mundi,” In Peter C. Bjarkman, ed., Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball Team Histories: National League (Westport: Meckler Publishing, 1991), 137-80.

10. David Porter, “Cap Anson of Marshalltown: Baseball’s First Superstar,” The Palimpsest 61, no 4 (July/August 1980): 98-107.

11. “Good-By to Anson,” Chicago Tribune, February 2, 1898, 4.

12. “Hart Writes of Anson,” Chicago Tribune, December 31, 1899, 18.

13. “Anson Replies to Hart,” Chicago Tribune, January 7, 1900, 17.

14. “Played 3000 Games,” Chicago Tribune, February 1, 1898, 4.

15. “Tribute to Anson,” Chicago Tribune, February 4, 1898, 4.

16. “Anson Won’t Take It,” Chicago Tribune, February 6, 1898, 7.

17. David Fleitz, “Cap Anson,” SABR BioProject.

18. “Anson May Get in Games,” Chicago Tribune, July 15, 1901, 2.

19. David Fleitz, “Cap Anson,” SABR BioProject.

20. Robert H. Schaefer, “Anson in Greasepaint: The Vaudeville Career of Adrian C. Anson,” The National Pastime, Vol 28, 2008.

21. “Capt. Anson, Baseball Hero, Dies at 70,” Chicago Tribune, April 15, 1922, 1.

22. Hugh Fullerton, “Even Ruth Unable to Touch Anson’s Role,” Chicago Tribune, April 15, 1922, 15.

23. “Notes,” Chicago Tribune, April 16, 1922, 26.

24. Hugh Fullerton, “Unveil Monument to ‘Cap’ Anson Today,” Chicago Tribune, September 16, 1923, 26.