Field of Schemes: The Spring Training Tryout of NFL Star ‘Jerry LeVias’

This article was written by Dan VanDeMortel

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Sunshine State (Miami, 2016)

In 1513, explorer Juan Ponce de Leon arrived in Florida, according to fable in search of the Fountain of Youth. Ever since, Florida’s menu of sun, fun, beaches, and citrus has symbolized renewal and regeneration, an “enchanted reality,” per state historian Gary Mormino, ripe for second chances amidst a constantly shifting dreamscape.1

Since the early twentieth century, Florida has offered the “enchanted reality” of spring training, with players and fans annually migrating to the Sunshine State for salubrious weather guaranteed to banish winter and welcome a fresh start. Dreams abound: a sharper curve, a quicker bat, fleeter feet, fewer aches and pains, a little bit more luck, making the team, a higher finish in the standings. Sportswriters, too, hear this suggestive call, the time when prose contracts the occupational disease “superlativitis,” as described by Sport magazine.2 The air tingles with possibility.

In February 1971, it seemed that Houston Oilers star receiver Jerry LeVias sensed that possibility even though he was at the pinnacle of a standout NFL career. The Beaumont, Texas, native had excelled as quarterback for his segregated high school. Upon graduation in 1965, he had blazed a trail as the first black scholarship athlete in the Southwest Conference, joining Southern Methodist University as a receiver in an era of racial turmoil. While there, he had lived alone and experienced racism from opponents and teammates in the form of hate mail, death threats, and on-field racially-motivated beatings. “My trademark was not to get tackled by more than one person so as not to end up under the pile. I tried to survive because I knew the things that would happen,” the 5-foot-10, 175-pound speedster later recalled.3 Encouraged during a brief meeting with Martin Luther King Jr., LeVias graduated in 1969, racking up All-SWC and All-American honors, and most SWC receiving records. Considered the “Jackie Robinson of the Southwest,” he was drafted by the American Football League’s Oilers, where he made the Pro Bowl as a rookie wide receiver and kick/punt returner. When the AFL merged with the National Football League in 1970, he joined the league of his Detroit Lions cousin, Mel Farr, and finished fifth in all-purpose yards.

LeVias hadn’t played baseball since he was an SMU sophomore, but he had been a .305-hitting second baseman. And he had stolen 52 bases in part-time high school ball, which had prompted the New York Yankees to offer a $30,000 bonus and a $12,000 annual contract.4 San Diego Chargers star halfback Mike Garrett had just cancelled a well-publicized plan to try out for the Los Angeles Dodgers, so the idea of an NFL star contemplating a career change to baseball was not unheard of at the time.

Detroit Tigers farm director Hoot Evers and chief scout Ed Katalinas began to receive calls in February from LeVias about a spring tryout, introducing himself as Farr’s cousin, explaining he loved and wanted to play baseball instead of football, which, “wasn’t really his game.”5 Katalinas procured an old scouting report on LeVias and conferred with Evers, who told LeVias he was welcome at the Lakeland Tiger Town training site if he could obtain the Oilers’ permission. LeVias quickly agreed. Katalinas told the press, “Our club is always looking for speed. He’s got two items on his side: unadulterated speed and great body control. He has what we call an infielder’s body. We have to find out if he has major league potential. After three weeks or so, he’ll know and we’ll know.”6

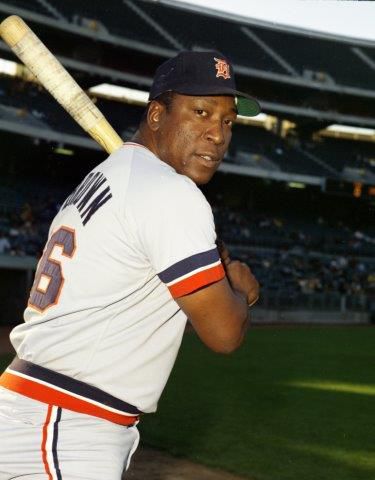

After obtaining Tigers infielder/pinch hitter Gates Brown’s phone number from the club, LeVias contacted him to advise that he was leaving football and would be reporting to Lakeland. Shortly thereafter, he showed up at Brown’s Detroit west-side bar under adversity, asking for a $300 loan for the round-trip airfare to Florida to help cover luggage lost on his flight to Detroit, a marriage to a woman in Atlanta, and funds tied up in Houston. Brown loaned the money and the two of them flew together with little additional conversation to Tiger Town on Friday, February 19.7

The Tigers team awaiting their arrival was undergoing its own regeneration. The 1968 World Series champions were recovering from a 1970 ordeal beset by more clubhouse drama than wins. To jumpstart success, Billy Martin had been signed to manage a revamped roster. This was the same diminutive but fiery Martin who would be hired and fired with clockwork regularity over his managerial career, as his brawls, alcoholism, and combative personality would repeatedly wear out his welcome.8 It was also the same Martin who was peerless as a tactician and who would rejuvenate every team he inherited, including the Tigers. He met with every player during the offseason to address problems and boost morale. “I’d play Adolf Hitler nine innings every day if he was the best man I had for the job,” he proclaimed, warning during the offseason, “I won’t put up with liars, alibi Ikes, or con artists.”9

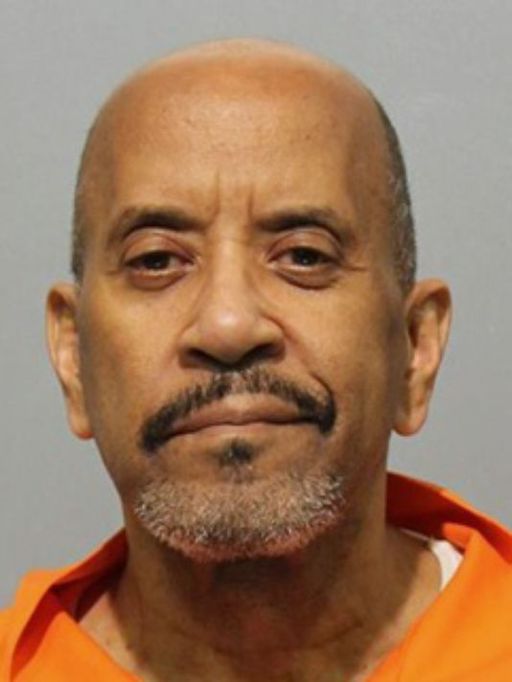

William Douglas Street Jr., shown here in a recent mugshot, has racked up multiple convictions for fraudulent impersonation. (Washtenaw County Sheriff)

In this atmosphere of high expectation, the Tigers rolled out the red carpet for LeVias. He was housed at the team’s newly built, three-story Fetzer Hall dormitory.10 A press release was issued. Potential snags were quickly averted. When LeVias explained that his Oilers’ written release was in luggage lost on the flight in from Detroit, along with Brown’s luggage, the team relaxed their rule and issued him a gray second-string uniform.11 Showing up without spikes equally proved inconsequential: a travelling sporting goods salesman handed over a pair of shoes with no payment due until their next meeting.

As LeVias donned his uniform, media, team officials, and players orbited about. In reports that would circulate nationwide, LeVias detailed his disappointment with football: “I’ve just lost all my feeling for football. I don’t ever want to go back. I’m just a little thing, you know, and I’m a little tired of getting belted around all the time. It was a mistake to play in Houston those two years. The players there didn’t give it all they’ve got. It’s tough to play when you’ve got a quarterback who won’t throw the ball to you because he’s jealous of all the attention you’ve received. And when I’d get hurt, the people wouldn’t believe me. I’ve been disenchanted with football ever since I got to Houston.”12

LeVias estimated he needed a half to a full season in the minors to move up to the Tigers and considered returning to school if he failed to make the cut. With camera snapshots exposing his face under a Tigers cap rather than concealing it behind an Oilers facemask, the man the Detroit News had dubbed “Speediest Rookie” headed for the field.13 When he strode toward the plate, the Tigers regulars stepped aside to let him bat.

As LeVias finished his swings and commenced fielding drills under veteran scout Bernie DeViveiros’s supervision, however, his skills appeared rawer than expected. “I wasn’t too impressed with the way he threw. Once in a while he would pop the ball a little with something on it, but right away I had my doubts. I watched him run and I wasn’t at all impressed. I just couldn’t see the speed that I was supposed to see,” DeViveiros recalled.14 “Something was clearly wrong with all his fundamentals,” added Katalinas, also in attendance.15 Once the 40-minute workout concluded, DeViveiros left the field muttering, “The fellow doesn’t look like an athlete to me.”16 Overall, he looked like “horse feathers,” observed another coach.17 Amidst swirling disappointment, LeVias remained undeterred, announcing he would issue a formal statement about quitting football in a day or two, and even asking for a monetary advance to tide him over.18

Meanwhile, an ominous cloud was heading toward his prospects. Once UPI picked up Detroit media coverage, the press contacted Oilers publicity director Jim McLemore for comment. Unaware of LeVias’s career change, McLemore called LeVias via the team’s contact information. The LeVias he reached was in Texas, though, where he was training for the upcoming football season. “This is a hoax,” McLemore quickly claimed to UPI after the workout.19 “Me quit football?” chimed in LeVias from Texas. “I don’t know where a thing like this got started. Biggest hoax I ever heard of.”20

Despite a tightening noose, the Lakeland LeVias insisted he was genuine to Detroit News beat writer Watson Spoelstra over two interviews, claiming papers to prove it were in his lost luggage. Finally, during a third interview with Spoelstra, nine hours after the tryout, LeVias came clean. News flash: His real name was Jerald Lee LeVias, not Jerry LeVias. Born in Detroit, the 23-year-old had graduated from Detroit Central High School where he was an All-City high school football player, and had recently gotten out of the Army and married when the imposter idea came to him. As for his raison d’etre at Tiger Town, the self-proclaimed lifelong Tigers fan offered, “I love baseball, that’s all. I figured I’d get a better chance if I were somebody.”21 Although of similar build to the receiver and having read about him in a magazine, Jerald Lee had only been to Houston once and had never seen Jerry play.

After quickly being contacted by Spoelstra and conferring with LeVias, and later general manager Jim Campbell, Evers announced, “The boy misrepresented himself and I’m sending him home. I don’t fault him that much if he wants to play baseball. But he went about it in a very wrong way. He seems like a very nice young man. He got some publicity he wasn’t deserving of and I’m certainly sorry.”22 Evers confessed he was “red-faced” and had erred in relaxing rules regarding the Oilers’ permission. “He said both his and Brown’s luggage had been lost at the airport…If one suitcase was lost we might have suspected something. But, when he said both were lost, it sounded right.”23 Katalinas was likewise embarrassed, oversold on LeVias showing up to camp with Brown. LeVias, meanwhile, retreated to a darkened room, refusing photographs. “I feel like a heel now…I had no idea the other LeVias was that popular. I just wanted to work out for a few days to show them what I could do. I was going to tell them the truth.”24

Gates Brown was the first Tigers player to be drawn in by Street’s scam when he lent the impostor $300 and accompanied him on an airline flight to spring training. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

The next morning, LeVias was flown back to Detroit. He recalled, “I began to feel a little guilty when they started taking all those pictures. I just didn’t expect to get all that attention. But, things were happening so fast, I didn’t know what to do. So I just went along with it.”25 With questionable self-analysis that as a “celebrity” he “shouldn’t have any trouble getting a tryout somewhere else now,” LeVias boarded with two airline- provided servings of Cutty Sark “hooch” for luggage to “get me a little drunk tonight” on the Tigers’ dime.26 Or, rather, on a $93 first-class departure ticket, which combined with Friday’s $72 team-covered coach arrival fare meant the Tigers paid $165 to be hoaxed and Brown was $300 lighter for an “airfare loan.”27 “Live and learn,” Brown lamented. “I’ll have to chalk it up to experience. I didn’t even know who Jerry LeVias was. Somebody in the front office gave him my phone number and that’s why I thought he was okay.”28

Before, during, and after departure, Jerald Lee’s hoax deepened. With his story publicized in Detroit, he was identified as William Douglas Street Jr. by a friend who recognized his picture. The “nice young man” man in actuality was a 20-year-old west-side Detroiter, the son of a bus driver and homemaker, who “couldn’t hit or pick up the ball” and was “equally as bad” at other sports, according to Central High’s baseball captain.29 Recently married to a local woman, not Atlantan, he’d decided that a life like his father’s was for “chumps,” but spent too much time “partying and goofing off” to obtain a profession.30 “I guess you can say I was always a man who believed in shortcuts,” he later admitted.31 A 1970 larceny conviction while posing as a Ferris State College student had been one of those short cuts.

Via enchanted reality and despite poor high school baseball skills, Street envisioned being a professional baseball player, his marriage certificate’s listed occupation, if given the opportunity. In 1969, he had finagled a summer workout with the Boston Red Sox when they visited Detroit. The following year, he had appeared at the team’s Winter Haven camp, fabricating that he had been called for a tryout. His skills were so poor, however, the Red Sox “got him off the field before he got killed” and paid for his return home.32 Later that summer, Street had appeared in Boston as a Time magazine writer covering Carl Yastrzemski, asking for and obtaining a uniform to work out with the team to get a “real feel for the story.”33 He was eventually tossed out after being caught warming up in the bullpen and shaving in the dugout during a game. Over subsequent months, Street had continued pestering the Red Sox, highlighted by receiving $50 while impersonating a Boston farmhand on a Detroit television show.34

Once Street’s full history hit the light of day, Campbell admitted, “We were taken by a real pro…I’m glad we didn’t get hurt more than we did.” Detroit News reporter Jerry Green, who had not bitten on the phony LeVias since he had seen the real LeVias in action, was amazed that Campbell had been so thoroughly hoodwinked since he was “such a straight-laced guy when it came to rules and regulations.”35

Street’s shenanigans fit perfectly with the Grapefruit League’s history of dreamers and schemers, some of whom even progressed to the Cactus League for more action. As Tigers coach Charlie Silvera recalled after Street’s escapade, some spent a few weeks drifting from club to club, getting a “sandwich and a coffee” for their efforts, the lucky few obtaining a recommendation letter from one general manager to another club.36 “You’d get a note saying the player was 6-foot-2, 190 pounds and when you’d get him, he’d be sawed off to 5-foot-1 and 110. Some really think they can play, but what they want most is to go to spring training. We used to have a lot of them, but not so much anymore.”37 “Dippers” who would “steal anything—dip into anything—wallets, clothes, rings, watches” also made the rounds.38 By 1971, however, sophisticated scouting and the free agent draft had virtually guaranteed that an unknown phenom making a team—like Billy Martin had while working out in unappreciated obscurity in Oakland after his high school graduation—were in history’s dustbin.

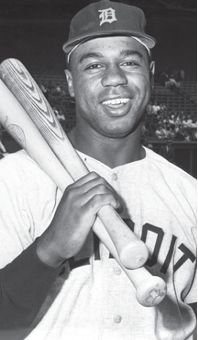

Street’s baseball-related impersonation efforts failed to find that same dustbin. On March 3 he was arrested at an Orlando hotel for passing a bad check on its manager under the guise of being with the Minnesota Twins. Returning to Detroit, he concocted a scam for “easy money” while drinking with friends.39 Knowing that Tigers slugger Willie Horton was in Florida, just past midnight on March 9, Street delivered a letter to Horton’s wife at the couple’s Detroit home. Horton’s wife recognized Street from his newspaper picture and refused to open the door. Identifying herself as Mrs. Horton’s sister, she instructed Street to leave the note. It demanded she withdraw $20,000 from her bank and turn it over to “this man.”40 “This man,” in turn, would hand over a briefcase of “pictures, tapes, and records of your husband’s criminal dealings,” warning her she would be killed if she contacted anyone and that her husband’s and children’s lives were at stake.41 Mrs. Horton immediately contacted the police. Shortly thereafter, Street was arrested and sentenced to 20 years’ probation for extortion. “That was some troubled times. We had to get security for my kids to go to school. What he put us through, I never wanted to see him again,” Willie Horton recalled.42

From 1973 onward, Street’s schemes veered toward surrealism. After violating his parole, he was sentenced to Southern Michigan prison, from which he escaped. By 2015, his lengthy confidence man resumé featured impersonations of a Michigan football player, a lawyer for the Detroit Human Rights Department, a medical student at Yale University, an Annapolis graduate, and a doctor at an Illinois Hospital, where he came close to performing an emergency appendectomy. He had totaled 25 convictions, 11 prison sentences, and numerous aliases, including one as a woman.43 In July 2015 the Plymouth township resident, living with a wife and special needs step-daughter, was sentenced to 23 months in state prison for issuing falsified checks. On February 8, 2016, he was sentenced to a consecutive term of 36 additional months on federal charges of mail fraud and aggravated theft of a Maryland-based Defense Department contractor’s identity used to pick up women and obtain a job. His lawyer describes him as “doing okay” and prepared—in the jailhouse phrase for serving time—to “go lay down for a while.”44 “I’m tired of this nonsense,” his client offered in court, “each day we choose who we will serve…and I chose incorrectly.”45

Later in spring training, Tigers slugger Willie Horton became entangled with Street when the con artist delivered a letter to his Detroit home demanding $20,000 and threatening murder if the police were contacted. Undeterred, upon receipt of the letter, Horton’s wife contacted the police and Street was quickly arrested. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Street’s life has been dramatized in Chameleon Street, which won the Grand Jury Prize at the 1990 Sundance Film Festival. Its director, after meeting with Street extensively, observed, “When he meets someone, he susses out within three minutes exactly who they want him to be, who they are, what hopes and aspirations they might have, how they digest the black persona and he becomes whatever is most advantageous to him.”46

In a current film industry beset by uninspiring sequels, Street’s life more deservedly calls for an updated Chameleon Street, or better yet a well-produced documentary. If Street participated in one, he would likely cite, as he did in a jailhouse interview, his impersonation of LeVias as, “the first time I found out how easy it was to get people to believe whatever you said, so long as you said it right.”47 Asked today the reason for his behavior, he might answer as he did in that same interview: “I don’t think of myself as an average guy out to prove something to the world. Sometimes, I think I’m just trying to prove something to myself.”48

DAN VanDeMORTEL became a Giants fan in Upstate New York and moved to San Francisco to follow the team more closely. He has written extensively on Northern Ireland political and legal affairs, and his Giants-related writing has appeared in San Francisco’s Nob Hill Gazette and The National Pastime. An investigation into the shooting of a spectator at the Polo Grounds will be published in 2017 in a Polo Grounds anthology. He is currently writing a book and related articles on the 1971 Giants and welcomes feedback at giants1971@yahoo.com.

Acknowledgments

Heartfelt appreciation goes out to baseball writer/editor Gary Gillette, SABR-Detroit chair, for his assistance with this article.

Notes

1. Gary Mormino, Land of Sunshine, State of Dreams (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2005), 2–3.

2. Jonathan Fraser Light, The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2005), 872.

3. Pro-Football-Reference.com (http://www.pro-football-reference.com/players/L/LeViJe00.htm) lists LeVias at 5’9″, 177 pounds. However, 1971 press accounts and his 1971 Topps and Kellogg’s football cards list him at 5’10”, 175 pounds; consequently, this measurement is relied on.

4. “LeVias Decides to Quit Football,” Wilmington Morning Star, February, 20, 1971, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1454&dat=19710220&id=FStkAAAAIBAJ&sjid=sQkEAAAAIBAJ&pg=5018,3426816&hl=en.

5. “The Amazing Mr. Street Goes South Again,” Pittsburgh Press, February 22, 1971, http://tigerlore.blogspot.com/2013/02/the-amazing-mr-street-goes-south-again.html?view=classic; “Tall Tale Grabs Tiger by Tail,” Jet, March 11, 1971, https://books.google.com/books?id=tjcDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA52&lpg=PA52&dq=tall+tale+grabs+tiger+by+tail&source=bl&ots=DTHsehWd0E&sig=vA2shwEEtvklZOnAkluoHikzb9o&hl= en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwijvbOG0KTKAhVK-2MKHVeGCvoQ6AEIHTAA#v= onepage&q=tall%20tale%20grabs%20tiger%20by%20tail&f=false.

6. Jerry Green, “Baseball’s Great Imposter,” Sports Scene, September 1971.

7. LeVias used a portion of the $300 to pay for Brown’s ticket. Brown slept through most of the flight.

8. In true fashion, Martin would guide an improved Tigers team to 91 wins in 1971 and one American League Championship Series win short of going to the World Series in 1972. Despite this success, by 1973 his relationship with general manager Jim Campbell had deteriorated so badly that he was fired in September while the team had a 71–63 record. His repeated etiquettorial remark, “Excuse me, I’ve gotta go take a Jim Campbell” when he used the restroom likely encouraged that development. Mike Shropshire, The Last Real Season (New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2008), 59.

9. Ed Linn, “Billy Martin: A Foreign Body in the Tigers’ System,” Sport, June 1971; Watson Spoelstra, “Martin Warns His Tigers: ‘I Hate Alibi Ikes,’” The Sporting News, January 30, 1971.

10.. Watson Spoelstra, “Tigers Are Red-Faced on Dead-End Street,” The Sporting News, March 6, 1971; Bill Rufty, “Tiger Town Dorm Getting $1 Million Renovation,” The Ledger, December 30, 2007, http://www.theledger.com/article/20071230/NEWS/712300465.

11. Brown later explained that his luggage was never lost; LeVias picked up the wrong suitcase at the airport. Once this error was discovered, they drove back and gathered the right one.

12. LeVias Decides to Quit Football,” op. cit.

13. Spoelstra, “Tigers Are Red-Faced on Dead-End Street,” op. cit.

14. “Tigers Fooled,” Hendersonville Times-News, February 22, 1971, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1665&dat=19710222&id=a8AmAAAAIBAJ&sjid=TiQEAAAAIBAJ&pg=5208,3447286&hl=en; “Tiger Imposter Feels Like Heel,” Oakland Tribune, February 22, 1971.

15. Richard Willing, “Will The Real William Douglas Street Jr. Please Stand Up,” Detroit News (Sunday Magazine), July 14, 1985.

16. Spoelstra, “Tigers Are Red-Faced on Dead-End Street,” op. cit.

17. Joe Falls and Jim Hawkins, “How a Kid With a Lot of Guts Pulled a Big Hoax on Tigers,” Detroit Free Press, February 22, 1971.

18. Jim Hawkins, “Our Man Jim Was Sweet-Talked, Too,” Detroit Free Press, February 22, 1971.

19. Watson Spoelstra, “‘Unitas’ Next for Tiger Tryout,’” Detroit News, February 22, 1971.

20. “Tigers Are Red-Faced on Dead-End Street,” op. cit.; “Tall Tale Grabs Tiger by Tail,” op. cit.

21. Spoelstra, “Tigers Are Red-Faced on Dead-End Street,” op. cit.

22. Watson Spoelstra, “‘Unitas’ Next for Tiger Tryout,” op. cit.; Green, op. cit.

23. “The Amazing Mr. Street Goes South Again,” op. cit.

24. Green, op. cit.

25. “Tiger Imposter Feels Like Heel,” op. cit.; Green, op. cit.

26. Joe Dowdall, “‘Tigers ‘Foul Ball’ Strikes Out Here, Too,” Detroit News, February 22, 1971; Green, op. cit.

27. In 2016 currency, the Tigers paid $967 for LeVias’s flights and Brown’s loan was $1,758.

28. Spoelstra, “Tigers Are Red-Faced on Dead-End Street,” Green, op. cit., see also, Joe Falls, “The Gator Believed ‘LeVias’—And He’s Out 300 Skins!,” Detroit Free Press, February 22, 1971.

29. Dowdall, op. cit.

30. Willing, op. cit.

31. “Professional Imposter Poses as Yale Student,” Daily New London, November 30, 1984, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1915&dat=19841130&id=2y1SAAAAIBAJ&sjid=CDYNAAAAIBAJ&pg=2180,6989111&hl=en.

32. Bill Halls, “Imposter Hit Others,” Detroit News, February 23, 1971.

33. Ibid.

34. $293 in 2016 currency.

35. Jerry Green, telephone interview, January 14, 2016.

36. Jim Taylor, “No Place for Dreams,” Toledo Blade, June 20, 1971, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1350&dat=19710620&id=DvNOAAAAIBAJ&sjid=1QEEAAAAIBAJ&pg=7173,4827973&hl=en.

37. Ibid.

38. Ibid.

39. Willing, op. cit.

40. “Warrant Is Sought Against Imposter in Threat to Hortons,” Detroit News, March 17, 1971; “Arrest Man Who Tricked Tigers for Threatening Horton’s Wife,” Ludington Daily News, March 17, 1971, https://news.google.com/ newspapers?nid=110&dat=19710317&id= bbpNAAAAIBAJ&sjid=FkoDAAAAIBAJ&pg= 1480,4151883&hl=en; “Willie Horton’s Wife Gets Imposter’s $200,000 [sic] Note,” Jet, April 15, 1971, https://books.google.com/books?id= jjcDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA28&lpg=PA28&dq=willie+horton%27s+wife+gets+imposter%27s+jet&source=bl&ots=1boACmZsyw&sig=USz3dc6BJ53u1obiskPMi5PMjNQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjJy7nC56TKAhUY32MKHW9sBHIQ6AEIHDAA#v=onepage&q= willie%20horton%27s%20wife%20gets%20imposter% 27s% 20jet&f=false.

41. “Willie Horton’s Wife Gets Imposter’s $200,000 [sic] Note,” op. cit.

42. Robert Snell, “Game May Be Up for ‘The Great Imposter,’” Detroit News, June 5, 2015, http://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/wayne-county/2015/06/04/epic-con-artist-chameleon-strikes-feds-say/28515197.

43. Ibid.; Willing, op. cit.

44. Joseph Arnone, telephone interview, January 15, 2016.

45. Jennifer Chambers, “‘Great Imposter’ Who Inspired Film Gets Prison Time,” Detroit News, February 8, 2016, http://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/wayne-county/2016/02/08/william-street-sentencing/ 80010360.

46. Robert Snell, “‘Great Imposter’ Pleads Guilty, Faces Almost 3 Years,’” Detroit News, September 30, 2015, http://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/detroit-city/2015/09/24/longtime-impostor-inspired-film-back-court/72726470.

47. Willing, op. cit.

48. Ibid.