For Whom the Ballgame Tolls: Ernest Hemingway Attends a White Sox Game Before Shipping Off to War

This article was written by Sean Kolodziej

This article was published in The National Pastime: Heart of the Midwest (2023)

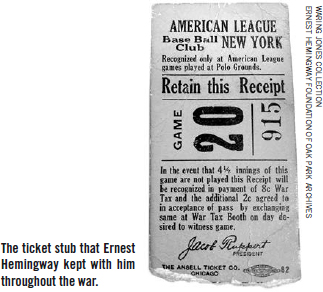

Baseball played a big part in Ernest Hemingway’s life. The subject was featured in many of his novels and short stories, including A Farewell to Arms and The Old Man and the Sea. One game that he attended in 1918 was so meaningful to him that he kept the ticket stub with him throughout his service in World War I as a volunteer ambulance driver and for many years after.

Ernest Hemingway was born in 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois, located just west of Chicago. It was a great place to be a fan. From the age of four until he left to serve in WWI at the age of eighteen, he witnessed exceptional baseball. During that time, at least one Chicago baseball team finished no worse than third place in their respective leagues every year, and the Chicago White Sox and Chicago Cubs each won two World Series. The Chicago Whales of the Federal League also finished in first place in 1915.

Hemingway was such a fan of the Chicago baseball teams that he ordered “action pictures” of Cubs players Mordecai “Three Fingered” Brown, Jimmy Archer, and Frank “Wildfire” Schulte from an advertisement in The Sporting News.1 He also ordered posters from Baseball Magazine of White Sox pitchers Big Ed Walsh and Ewell “Reb” Russell.2 He went to games with his father and would study the upcoming schedules to pick out certain games to attend. In a letter to his father from early May 1912, Hemingway asked if they could go to the May 11 game between the Chicago Cubs and New York Giants.3

The 1917 World Series between the Chicago White Sox and the New York Giants made a big impression on Hemingway and he would later write about it in his short story “Crossing the Mississippi.” The young man in the story, Nick Adams, would go on to appear in many Hemingway short stories and is partly inspired by Hemingway’s own experiences. After witnessing Happy Felsch’s game-winning home run at Game One in Chicago, in the story Nick travels to Kansas City to find work. Hemingway, in his real life, also went to Kansas City around this time to work for the Kansas City Star. While on the train, Nick (and one can assume Hemingway himself) finds out that the White Sox have won the Series and is filled with a “comfortable glow.”4

While at the Kansas City Star, Hemingway had the opportunity to interview members of the Chicago Cubs as they traveled to spring training in March 1918. He bought Coca-Colas for Claude Hendrix, Pete Kilduff, and Grover Cleveland Alexander, whom he referred to as “the worlds (sic) greatest pitcher.”5

In early 1918, Hemingway joined the war effort when he volunteered to be an ambulance driver for the American Red Cross in Italy. He was sent to New York City on May 13, 1918, for training. On Wednesday, May 22, right before he was to ship out to Europe, Hemingway was able to attend a ballgame. Luckily for him, the Chicago White Sox were in town playing the New York Yankees at the Polo Grounds.

As the United States had entered WWI about a year prior to this game, the Yankees announced that 25% of the gross receipts from the game would be given to the Clark Griffith Bat and Ball Fund, which provided baseball equipment for soldiers who were stationed in Europe. The New York Tribune stated that “no less than nine companies of soldiers, many of them with their bands, will be on hand.”6 Prior to the game, the soldiers were paraded around the field. Because of the overcast weather, only 5,200 total fans attended the game that day, although the Polo Grounds could have held around 38,000 spectators.

The White Sox, winners of the prior year’s World Series, had just lost their star outfielder, Shoeless Joe Jackson, less than two weeks earlier; he went to work at a Delaware shipyard to avoid the draft. To make matters worse, their starting pitcher for the game, Eddie Cicotte, was still winless with an 0-5 record.

The Yankees would be starting Herb Thormahlen, who was carrying a 19-inning scoreless streak into the game. Having appeared in only one game the previous season, the 21-year-old lefthander was unfamiliar to the Chicago sportswriters. His “name makes you think of some kind of tooth powder or disinfectant,” wrote I.E. Sanborn of the Chicago Daily Tribune.7

The game went into extra innings as both pitchers were dominant throughout. In the 12th inning, Buck Weaver hit a drive to right field that looked like it might clear the fence, but Frank Gilhooley “leaped into the air and caught the ball as it was about to impinge on the stands, and then fell headlong in the mud.”8

Both teams saved their most dramatic play for the 14th inning. In the top half of the inning, the White Sox loaded the bases with only one out. Unfortunately for the White Sox rooters, Buck Weaver could only manage to hit a grounder to third baseman Frank “Home Run” Baker, who threw home to easily force out Nemo Leibold. Chick Gandil then flew out to center field to end the inning.

With one out in the bottom of the 14th, the Yankees’ Baker and Del Pratt hit back-to-back singles. Wally Pipp then hit a single to center that drove in Baker for the winning run.

It was a tough loss for the White Sox, especially for Cicotte. He gave up only four hits through thirteen innings before finally losing the game one inning later. The Buffalo Enquirer reported that “Eddie Cicotte’s opinion of that fourteen-inning 1-to-0 defeat at the hands of the Yankees had been deleted by the censor.”9

The game must have made an impression on Hemingway. On July 8, 1918, Hemingway was badly wounded in both legs while bringing chocolate and cigarettes to the soldiers on the front line in Italy. He spent six months at the Red Cross Hospital in Milan, and did not return to the United States until January 1919. Throughout all of this, the ticket stub remained with him. The stub from that New York game between the White Sox and Yankees can now be found in the Hemingway Archives in Special Collections at the Oak Park Library.

The following year, the Chicago White Sox lost the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds. Hemingway believed that the White Sox were playing on the level and bet on them to win. After Shoeless Joe Jackson, Eddie Cicotte, and Lefty Williams confessed to throwing the series, a friend made fun of Hemingway for betting on the White Sox. As he wrote to a friend, “I was informed by Deggie that it served me right to lose when I bet on the Sox last fall. Thinking the series was honest.”10

Even after the scandal, Hemingway remained enough of a White Sox fan that he attended a White Sox-New York Giants exhibition game in France in November 1924.11

Later in life, Hemingway would reminisce about growing up watching baseball. He used a baseball metaphor to describe his own writing: “When I was a boy a pitcher named Ed Walsh, spit-ball pitcher for the Chicago White Sox, won 40 ball games one year for a team that rarely gave him more than a one run lead. Am working on this precept. Somebody said of him, Walsh, that he was the only man who could strut sitting down. I can strut when on my ass and will.”12 Based on Hemingway’s reputation as one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century, winning the 1954 Nobel Prize in Literature, one can assume that he was right.

SEAN KOLODZIEJ, a SABR member since 2018, is a lifelong Cubs fan. He was born, raised, and still lives in Joliet, Illinois, with his wife, Amy. His greatest moment at Wrigley Field was watching Glenallen Hill hit a home run onto the rooftop of a building on Waveland Avenue.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Kheir Fakhreldin, archivist in Special Collections at the Oak Park Library, who provided considerable research assistance in the writing of this article.

Notes

1. Ernest Hemingway letter to Charles C. Spink and Son, circa 1912 in The Letters of Ernest Hemingway 1907-1922. Vol. 1; eds. Sandra Spanier and Robert W. Trogdon (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 11.

2. Ernest Hemingway letter to Base Ball Magazine, April 10, 1915 or 1916, in Letters, Vol. 1, 18-19.

3. Ernest Hemingway letter to Clarence Hemingway, circa second week of May 1912, in Letters, Vol. 1, 12.

4. Ernest Hemingway, The Nick Adams Stories (Amereon Limited: New York, 1972,) 134.

5. Ernest Hemingway letter to Clarence Hemingway, March 14, 1918, in Letters, Vol. 1, 90.

6. “Soldiers to Get Baseball Goods at Polo Grounds” New York Tribune, May 22, 1918, 14.

7. I.E Sanborn, ”Sox Lose 14 Round Battle to Yankee Slab Rookie, 1 to 0,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 23, 1918, 11.

8. “Thormahlen Pitches 34th Runless Inning,” New York Tribune, May 23, 1918, 12.

9. Jack Veiock, “Score Board Reflections,” Buffalo Enquirer, May 23, 1918, 14.

10. Ernest Hemingway letter to Grace Quinlan, September 30, 1920, in Ernest Hemingway: Selected Letters, 1917-1961. Ed. Carlos Baker (New York: Scribners, 1981), 41.

11. Ernest Hemingway letter to Howell Jenkins, February 2, 1925, in Selected Letters, 148.

12. Ernest Hemingway letter to Charles Scribner, August 25-26, 1949, in Selected Letters, 667.