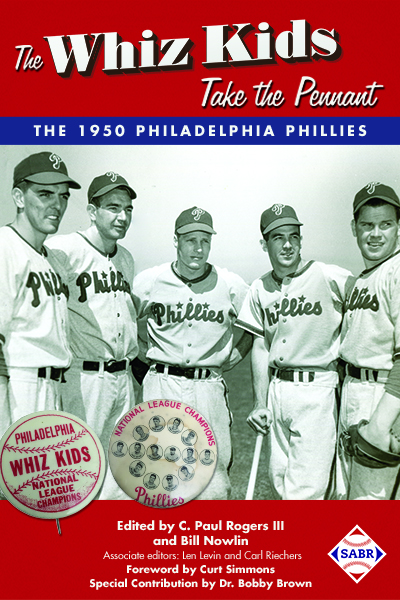

Foreword: The Whiz Kids Take the Pennant

This article was written by Curt Simmons

This article was published in 1950 Philadelphia Phillies essays

I was just 20 years old heading into the 1950 season with the Phillies, but starting my third full year in the big leagues. At the end of the 1949 season, the Phillies were on the upswing, finishing in third place after many years in the cellar or deep in the second division. The owner, a young guy named Bob Carpenter, had started paying hefty bonuses to prospects after the war, and it was beginning to pay off. Some of the young guys like Richie Ashburn, Granny Hamner, Robin Roberts, Del Ennis, and Willie Jones were coming on strong and there was a lot of optimism on the team that we could win the pennant in 1950. I frankly wasn’t all that optimistic, maybe because as a 20-year-old I had struggled to a 4-10 record in ’49. But I was always a pessimist, probably because of the Pennsylvania Dutch in me. Every spring my buddy Robin, who was an optimist, and I would argue about how we were going to do. I’d look at the Dodgers lineup and wonder how we could beat them, and then I’d look at our club and think that we had too many holes. Of course, I went out there and battled all season along with everyone else, and when we won the pennant in 1950 it was a very pleasant surprise.

I was just 20 years old heading into the 1950 season with the Phillies, but starting my third full year in the big leagues. At the end of the 1949 season, the Phillies were on the upswing, finishing in third place after many years in the cellar or deep in the second division. The owner, a young guy named Bob Carpenter, had started paying hefty bonuses to prospects after the war, and it was beginning to pay off. Some of the young guys like Richie Ashburn, Granny Hamner, Robin Roberts, Del Ennis, and Willie Jones were coming on strong and there was a lot of optimism on the team that we could win the pennant in 1950. I frankly wasn’t all that optimistic, maybe because as a 20-year-old I had struggled to a 4-10 record in ’49. But I was always a pessimist, probably because of the Pennsylvania Dutch in me. Every spring my buddy Robin, who was an optimist, and I would argue about how we were going to do. I’d look at the Dodgers lineup and wonder how we could beat them, and then I’d look at our club and think that we had too many holes. Of course, I went out there and battled all season along with everyone else, and when we won the pennant in 1950 it was a very pleasant surprise.

In fact, the Whiz Kids, as we came to be known, had a lot of battlers. We played hard and had guys come through in the clutch all year long. I don’t know how many one-run games we won that year, but I can tell you that it was a bunch. It seemed like almost every game went down to the wire, and we won more than our fair share. Del Ennis had a monster year and led the league in RBIs, and guys like Hamner, Jones, Dick Sisler, and Mike Goliat had career years. Andy Seminick at catcher also had a career year hitting and was an immovable object behind the plate. Robin broke through with his first 20-win season and rookie pitchers like Bubba Church and Bob Miller came out of nowhere and were terrific until they got hurt.

Then there was Jim Konstanty, whom we called Yimca because he looked and acted like a YMCA instructor. Jim probably had one of the best years any relief pitcher has ever had. He won 16 games, all in relief, and set the record for most appearances by a pitcher with 70 on the way to the National League MVP award. Of course, the fact that Konstanty won that many games in relief also illustrates that we won a lot of games late with clutch hitting. We had guys battling and coming through in the clutch all year long.

I also finally got straightened out and won 17 games before I had to leave for the service, so I certainly played a significant role in our success. As I mentioned, I’d really struggled before that ’50 season after signing for a big bonus in 1947. Because of the bonus rule, I’d been with the team in ’48 and ’49 but couldn’t really get squared away. I had some success and could really throw hard, but I wasn’t consistent. I had a real herky-jerky motion and I’d stride toward first base and throw across my body instead of opening up like a pitcher is supposed to. George Earnshaw was a roving pitching coach for the Phillies and he was always harping about the position of my legs, trying to get me to square up. I tried all that stuff, but I’d end up not being able to throw the ball because I’d be thinking about my legs.

I wanted to be a winner, so I was willing to try whatever the teams suggested. They were my coaches and I’m 18 or 19 years old and didn’t realize that I was that herky-jerky. I thought I was fairly smooth. There was no video camera in those days to show me otherwise.

Finally in spring training in 1950, Eddie Sawyer, the manager, and Cy Perkins, one of the coaches, told me to just do what came naturally and to throw like I had in high school in Egypt, Pennsylvania. Ken Silvestri was our bullpen catcher and he was also great at boosting my confidence.

At the end of spring training we barnstormed our way north from Florida for a couple of weeks, playing against Double-A and Triple-A teams, and I pitched well. I was getting the ball over and nailing down these high minor leaguers. So that gave me some confidence to start the season and finally, after two years in the big leagues, I just went out and pitched well and won a bunch of games.

We were in contention all year and finally took over first place for good in late July. Eddie Sawyer had a lot to do with our success that year. He was the professor, very even-keeled, not too high or too low. We had very few meetings and Eddie didn’t talk to us much. He certainly wasn’t a holler guy. Under Sawyer we just played pretty much straight baseball. We didn’t hit and run or steal much or have trick plays. In fact, our signs were so simple that I’m sure the other teams had them. We relied on our pitching, and focused on catching the ball and scoring a couple of runs.

Of course, I missed the late season excitement because my National Guard unit had been called to active duty because of the outbreak of the Korean Conflict. The previous year Bob Carpenter had asked Charlie Bicknell, another bonus baby pitcher, and me to join the National Guard in Philadelphia. He was trying to protect his investment in us so that we could avoid the draft, and the way he asked, we really had no choice. So I was a weekend warrior in the National Guard in Philadelphia, meaning I had to spend one weekend a month with the Guard and then serve two weeks active duty during the summer.

On August 1 I got word that my unit would be activated in about 30 days and would be sent to Camp Atterbury in Indiana for basic training. Frank Powell was our traveling secretary and he kept telling me not to worry, that I’m not going, that the club was going to get an extension for me so that I could finish the season. Of course, I didn’t want to go, I wanted to stay with the team. Then on September 10, while I’m getting on the train to go to Camp Atterbury, Frank tells me, “Don’t worry. We’re going to get you back.” But they didn’t get me back, so I missed it.

Charlie Bicknell, who by then had been traded to the Braves organization, was activated too and when we go to Camp Atterbury, we tried to keep in some kind of shape by throwing to each other. But mostly we had to try to get the camp into shape, since it hadn’t been used for a while.

I was following the Phillies in the paper and on the radio as much as I could during that stretch drive. When it looked like we might blow the pennant, all my new camp buddies wearing the same uniform were on me pretty good, giving me the ole raspberry.

Of course, I was still at Camp Atterbury during that last weekend against the Dodgers in Ebbets Field and the last game that went 10 innings. I couldn’t stand to listen to the game on the radio, so I was out playing touch football all afternoon. Finally, a guy hollers out, “Hey, Sisler hit a home run! The Phillies won!” What a relief it was to hear that. That evening my teammates had a big party at the Warwick Hotel when they got back to Philly and they called me at the base, so I got to talk to Robbie, Willie Jones, and a bunch of the guys.

A few days before the World Series the Army told me that they’d give me a 10-day unpaid leave to go to the World Series. Of course I took the leave, but by that time the Phillies had set up their Series roster and I think Eddie Sawyer was reluctant to put me on it because I really hadn’t pitched for about three weeks.

I remember that when I got off the Army transport plane in Jersey City, I was half asleep but someone from the Philadelphia Daily News met me and offered me $500 for a daily ghostwritten column on the Series under my name. Then later I did some on-the-air commercials for Gillette Safety Razors during the Series. I was scared to death, but it got me some more extra cash. The team had voted me a full World Series share, so I told everyone I was making more than they were by not playing.

I pitched batting practice before the Series games but wasn’t allowed to sit in the dugout during the games, so I’d put on my military uniform and watch the games from the press box. During batting practice the guys were moaning because I was breaking their bats. I didn’t think I was throwing too hard but I guess it was more than they were used to, at least in batting practice. Some of them said I pitched them into a slump, since we didn’t hit much in the Series. But I think Raschi, Reynolds, Lopat, and Ford had more to do with our not hitting than I did.

It was tough missing the Series, especially since the Phillies didn’t make it back for 30 years. We lost the first three games to the Yankees by one run in low-scoring games and had the tying run at the plate in the ninth inning of the fourth game, but couldn’t get over the hump. I’d like to think that I might have made a difference if I’d been able to pitch, but that’s ancient history now. As it was, it took me another 14 years to finally pitch in a World Series. I finally made it with the Cardinals in 1964 when I was 35 years old. I won 18 games that year and started two games against the Yankees in a Series the Cards won in seven games. Of course, that was the year of the Phillies’ famous collapse which allowed the Cardinals to sneak in at the wire.

But back to 1950, it was a special year and I’m proud to be remembered as a Whiz Kid. It was a little bittersweet for me personally, because of my military service at the end of the season. I turned 21 that year, so I didn’t fully comprehend everything and probably didn’t fully appreciate our success then. But the ’50 Whiz Kids were a special group of guys who battled all year and came together to win a pennant. Looking back, I wouldn’t trade those memories for anything.