Four Girls in Spring 1974: The First Foot-Soldiers of Female Inclusion in Little League Baseball

This article was written by Charlie Bevis

This article was published in Spring 2022 Baseball Research Journal

This article was honored as a 2023 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award winner.

The names of Jenny Fulle, Amy Dickinson, Elizabeth Osder, and Janine Cinseruli are rarely, if ever, mentioned in the existing literature regarding the integration of female ballplayers into Little League Baseball. These four girls were pioneers on the ground in the first wave of judicially authorized females to play in the renowned youth baseball organization that, at the time, was only open to 8-to-12-year-old boys.1

Fulle, Dickinson, Osder, and Cinseruli were among the dozens of aspiring preteen female baseball players in Spring 1974 who experienced firsthand the tribulations of cracking the all-boy barrier that had been national policy in Little League Baseball since 1951. These four girls provide real-world context to the principle-based legal ruling in New Jersey that opened the door to sex integration on March 29, 1974. That ruling ignited raging ideological battles in local leagues across the country until the national office of Little League Baseball consented on June 12, 1974, to allow girls and boys to compete together.

These early foot-soldiers were a trial group for Little League sex integration. They put into live action the dry legal arguments to demonstrate that female inclusion could occur without negative consequences to athletic competition or societal mores. These efforts in Spring 1974 helped to accelerate the eradication of sex discrimination, resulting in a timeline of ten weeks rather than the months or years that an absolute focus on legal arguments could have taken to obliterate this barrier in youth baseball.

What distinguishes Fulle, Dickinson, Osder, and Cinseruli from the other 1974 foot-soldiers is the deeper historical record of their experience, which extends beyond a short snippet in 1974 newspaper articles that most of their compatriots typically received. The stories of these four girls have been pieced together in this article not only from material contained in contemporaneous newspaper accounts (by both national wire services and local writers), but also from archival images, periodical articles during the ensuing two decades, and recently published retrospective thoughts as an adult.

BACKGROUND ON EARLY FEMALE PIONEERS

History has largely focused on Kathryn Johnston and Maria Pepe as the pioneers of Little League sex integration. Their actions provided a foundation for the landmark 1974 legal decision, thirty-five years following the establishment of Little League Baseball in 1939.

Johnston was the first girl to appear in an official Little League baseball game. Playing in 1950 for the King’s Dairy team in Corning, New York, she disguised herself as a boy and went by the nickname “Tubby.” In 1951 the national office of Little League Baseball promulgated its all-boy, sex-exclusionary rule stipulating that “girls are not eligible under any conditions,” precipitated by its discovery of Johnston’s participation.2

The bedrock principle underlying the barring of female players, as captured in the existing literature, was the preservation of Little League’s perceived role “in the power of sport to shape society and groom males for leadership roles in political, business, and social realms.” This was a continuation of the male-focused patriarchal vision of America, with its preconceived notions of a subservient feminine role and masculine role in sports, especially the one termed the national pastime. “It was not surprising that the organization battled the admission of girls,” Eileen McDonagh and Laura Pappano observed in Playing with the Boys: Why Separate Is Not Equal in Sports. “But it was surprising how little the actual fight had to do with athletic ability and how much it had to do with preserving male power and tradition.”3

In 1964, Little League Baseball, originally incorporated in the state of New York, was granted a federal charter as a non-profit corporation through a federal law passed by Congress. The charter included the following corporate objective beyond imparting baseball skills: “assist boys in developing qualities of citizenship, sportsmanship, and manhood.” This clause re-enforced the 1951 rule prohibiting girls and firmly established the organization as an all-male bastion. As Marilyn Cohen noted in No Girls in the Clubhouse: The Exclusion of Women from Baseball, before 1974, under the guise of this federal charter, “it was the standard practice of Little League Headquarters to threaten the revocation of the charter of any local league allowing girls to play.” In 1973, the organization successfully used this tactic in court to revoke the charter of a league in Ypsilanti, Michigan, that had allowed Carolyn King to be a player.4

Maria Pepe inspired the New Jersey litigation that ultimately led to the dismantling of the Little League sex barrier. In 1972 she participated in the Little League tryouts in Hoboken, New Jersey, acknowledging she was female, and was selected to play for the Young Democrats team. After playing in three games, Pepe was dismissed from the team after the national office of Little League Baseball employed its tried-and-true threat of charter revocation to influence local officials to drop Pepe from the league.5

In May 1973, the National Organization of Women (NOW) pursued Maria’s legal case by filing a complaint with the New Jersey Division on Civil Rights. NOW argued that Little League Baseball was a public accommodation and thus could not discriminate on the basis of sex. Little League Baseball defended its position by focusing on a two-pronged argument: (1) the physical difference between boys and girls, which would result in injury to girls, and (2) its federal charter that required a single-sex program for the betterment of boys.6

On November 7, 1973, an examination officer in the New Jersey Division on Civil Rights dismissed Little League Baseball’s arguments and ruled that local leagues in New Jersey had to accept girls. Little League Baseball exercised its right to appeal to the Appellate Division of the New Jersey Superior Court, which on March 29, 1974, upheld the ruling of the Division on Civil Rights. These legal decisions enabled girls in New Jersey to officially participate in baseball tryouts in Little League during Spring 1974, and set the stage for court cases in other jurisdictions across the country.7

News coverage of girls at baseball tryouts initially focused on Hoboken, the hometown of Maria Pepe, now 14 years old and ineligible for Little League, where fifty girls reportedly tried out in late March. A photographer captured the image of five girls with baseball gloves sitting underneath a Hoboken Little League sign as they awaited tryouts. That picture is now in the Library of Congress photo archive.8

During the ten-week period following the March 29 decision, pending further legal appeal by Little League Baseball, several local leagues nationwide accepted girls under court order. The following sections detail the stories of Fulle, Dickinson, Osder, and Cinseruli, amplified by long-forgotten newspaper reports of their youth and more recent life-lesson reflections as an adult. Their baseball experiences also illustrate the endemic issues noted above that precluded rapid expansion of female inclusion during the next several decades.

JENNY FULLE IN CALIFORNIA

On April 10, 1974, reporters from San Francisco-area newspapers and national wire services gathered to watch 11-year-old Jenny Fulle at her first baseball practice in the Mill Valley Little League, after a judge signed a court order preventing the league from keeping her out of the league. Mill Valley is located in suburban Marin County across the bay from San Francisco.

As reported in her local newspaper, the Daily Independent Journal, Fulle “finally took her place on a league team yesterday and began batting balls over her teammates’ heads.” Most of her teammates on the Bears team seemed satisfied with her progress as a ballplayer. “I thought we’d have a crappy girl, but she’s good,” one boy commented. Because she was joining the league late, she couldn’t try out for the major-league division. “But I’m happy being on a minor-league team,” Fulle said. “And I’m glad to get to play at least one season with the Little League.” She would turn 12 years old that summer and not be eligible to play the following year.9

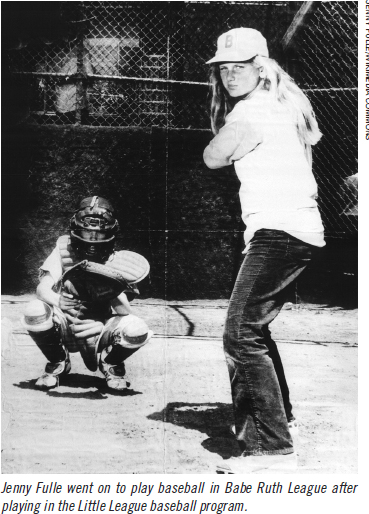

Both Associated Press and United Press International released a photo of Fulle, dressed in bell-bottom jeans and swinging a bat, which newspapers nationwide printed. She perhaps would have received greater acclaim for her effort in baseball history had her name not been misspelled as Jenny Sulle in the caption to the wire-service photograph. Unfortunately, it was not the first time that the wire services bungled the spelling of her surname.10

The press had been interested in her story since 1973 when Jenny received a reply to her letter to President Nixon that had complained about sex discrimination, after she had been turned away from Little League tryouts in 1972. Fulle had played in pickup baseball games for several years with the boys in her neighborhood and naturally just assumed she could sign up to play in the local organized league.

“Jenny Fulles [sic], a 10-year-old fifth grader from Mill Valley, California, got so peeved she wrote a letter to the White House,” the Associated Press wrote about Fulle’s situation, misspelling her last name. The Department of Justice replied to Jenny, saying it was “preparing guidelines to handle this type of discrimination.” As Fulle told the AP reporter, “It made me so mad. There are lots of girls who want to play and lots of boys who want us to play.” Fulle punctuated her thoughts by adding, “I agree with almost everything I know about women’s lib.”11

The local chapter of NOW pushed Fulle’s case with the Mill Valley City Council, arguing that the Little League should be stopped from using a public baseball facility for its games unless girls were allowed to play and thus end its sex discrimination. While the City Council initially concurred, later in 1973 it reversed its decision after Little League Baseball threatened to revoke the league’s charter, which councilmen argued would deprive 350 boys of playing baseball in 1974. “They shouldn’t have backed down on the decision. I didn’t like it,” Fulle told a reporter from the local Daily Independent Journal. “Last spring I watched a lot of games. Maybe I’ll do the same thing this spring. And after I turn 12 they might let me be umpire.”12

Years later, Fulle gave an extensive oral history interview in June 2017 to add some color to the facts of her effort to introduce female inclusion into Little League in Mill Valley. As she recounted, the City Council meetings had their ugly moments, with hecklers shouting nasty statements about Fulle, and she was teased by some of her classmates. But the ACLU then took her case to federal court, where she received a favorable ruling in April 1974. After her one year of Little League, Fulle played in the local Babe Ruth League in 1975 before moving on to girls-only softball, after inspiring a number of girls in Mill Valley to pursue baseball in Little League.13

In interviews she gave as an adult, Fulle was sanguine about her baseball adventure. “I definitely loved playing, and at a young age, having that victory set me up to break through roadblocks for the rest of my life and to believe that anything is possible.” Since her adult occupation was film executive, Fulle expressed her thoughts about a certain youth-baseball movie. “The Bad News Bears came out a few years later, and I always thought, OK, that’s not fair, I played for the [Mill Valley] Bears,” she jokingly recalled. “I thought the Tatum O’Neal character should have been me.”14

Fulle may be the only sex-integration foot-soldier from 1974 with a monument erected to commemorate her feat. In 2017 a plaque was embedded in a boulder at the public park in Mill Valley where she had played baseball. The first sentence of the plaque reads: “On this field on April 20, 1974, Jenny Fulle became the first girl across America to officially play in Little League.”15

AMY DICKINSON IN NEW JERSEY

In the earliest days of the 1974 Little League season in Tenafly, New Jersey, two New York City newspapers published photographs of nine-year-old Amy Dickinson. She was shown swinging a baseball bat in the New York Daily News and standing beside her much shorter teammates in The New York Times.16

At the Tenafly tryout session, 27 girls and 349 boys displayed their batting and fielding skills indoors to team coaches. “There was a smothered chuckle from the gym stage when Amy Dickinson, a 9-year-old greeneyed redhead, punched her fist into a mitt and easily caught the high and low ones sent her way,” the Daily News reported. “It was nothin’ really,” Dickinson said afterward. “I just wanted to play and I play with boys all the time, anyway.”17

Dickinson stood out among the 150 kids assigned to a minor-league team, as the first draft choice by team coaches. “She was superior to all the boys,” one coach told the New York Times reporter. Later in the season, Dickinson said that most of the boys on her team “don’t really care” about whether girls play, adding that “most of them don’t pay any attention.”18

She was a good baseball player, an all-star for three years at the minor-league level. In 1976 she had a 4-2 record as a starting pitcher and compiled a .382 batting average as a hitter. However, Dickinson had concerns about moving up to the major-league level as a 12-year-old in her final year of eligibility.19

The concerns were not just with baseball skills, though, that led Dickinson to her second thoughts about baseball. “She doesn’t want to be a tomboy anymore and may well hang up her sneakers,” Jane Leavy wrote about Dickinson in a 1977 article in womenSports magazine, excerpts of which were printed nationwide in wire-service newspaper articles. “She wants boys to think of her as a pretty little girl, rather than a no-hit pitcher. She is worried that if she is too good a ball player, those same boys won’t think of her as a girl.”20

Dickinson had bittersweet memories of her Little League experience, as she said in an interview in 1989 upon the fifteenth anniversary of female inclusion in Little League. “I liked the game very much. But in retrospect, I don’t think I had such a good time,” she said. “The first time I saw myself on the TV news, I started to cry. I didn’t want all the attention.”21

In 2004, Dickinson continued to be remembered for her selection as a top draft choice in 1974, at the death of her Little League coach, Donald Miller. “Mr. Miller broke an unwritten rule by choosing Amy Dickinson, but not because he was an activist,” Miller’s son noted in an obituary. “He did it because she could hit. He realized it was a big deal, but he was focused on her hitting. It worked out great. He didn’t lose many games.” Dickinson added: “I know he got a lot of guff for picking me. But he was very proud of that. I think he kept the picture of us in the newspaper hanging in his bakery. He was very modern-minded.”22

ELIZABETH OSDER IN NEW JERSEY

On April 21, 1974, the New York Daily News published on its front page a photograph of nine-year-old Elizabeth “Bitsy” Osder standing in the batter’s box at the season-opening Little League game in Englewood, New Jersey. Osder’s image shared the front page of the tabloid newspaper with the banner headline “A New Hearst Kidnap Mystery,” referring to millionaire heiress Patty Hearst and her unclear role in a recent bank robbery, either as coerced hostage or knowing participant with her kidnappers.23

An article about Osder’s play during that game appeared on page 3 of the Daily News. Bitsy, “who, to her chagrin, also is known as Elizabeth,” showed her spunk on the ball field, not intimidated by being the only girl on the field in the otherwise all-male cast of Little League. After striking out in her first at-bat, she slammed down her bat in disgust, but she then drew a walk in her next at-bat and scored a run. In the dugout, “Bitsy was all mouth, first complaining of a cramped arm, then challenging the umpire’s calls, and finally giving instructions to fielders.” Despite her exuberance, the Daily News reporter observed that the coaches and players openly accepted Osder as a teammate.24

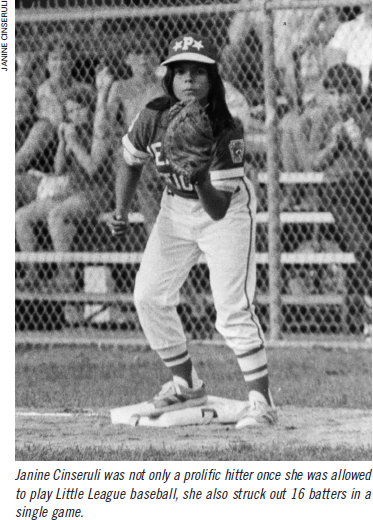

Daily News photographer Bill Stahl Jr. snapped several pictures of Osder as second baseman in the field, as well as other photos of her in the batter’s box. Two more of Stahl’s photographs of Bitsy from that game accompanied the Daily News article, which were reproduced in newspapers nationwide a few days later, providing a small degree of national acclaim for young Bitsy.25

What makes these photos from April 21, 1974, most remarkable, though, is their current existence online (along with several other photos from that day) in the extensive Getty Images archive. These photos are the sharpest images publicly accessible for one of the first wave of girls to play baseball in Little League during 1974.26

In 1975, 10-year-old Osder moved up from the minors to play on a team in the major-league division. “I’m glad I’m in the majors, but I’ll probably be benched a lot more,” she told a Daily News reporter. “I like second base, but I don’t know where I’ll play this year,” she added. The reporter termed Osder’s demeanor in the interview as “total professionalism.”27

The front-page photograph in 1974 ironically inspired Osder’s career choice as a website designer. “Osder became fascinated with the process of how that image could be transmitted and published in such a short period of time,” Christopher Harper wrote in the 1998 book And That’s the Way It Will Be: News and Information in a Digital World. Osder went on to study photography in college and deploy her creative juices in designing web sites in the then-revolutionary world of the Internet.28

As for her four years of Little League, “It was the first big thing in my life I had really wanted to do, and no one said ‘no, you can’t’,” Osder explained in an interview in 2000 as an adult. “I loved baseball, and had the answer been ‘no,’ I think it would have changed my take on life. Now, I never approach anything with the assumption that the answer will be no.”29

“It gave me a love for team sports and the camaraderie of teammates,” she recalled in a 2021 interview. “There were no conflicts with my playing and my team celebrated our little bit of celebrity status together and has stayed close over the years. Teamwork has always been the heart of my work and sense of community, and it was cemented in my experience in Little League.”30

JANINE CINSERULI IN MASSACHUSETTS

On May 19, 1974, 10-year-old Janine Cinseruli was finally granted a tryout for the Little League in Peabody, Massachusetts, a suburban town thirteen miles north of Boston. Although Cinseruli “missed the first five pitches thrown to her,” the Boston Globe reported that she “hit the next ten pitches, and impressed one coach, who called her ‘the best performer on the field.’”31

Cinseruli’s tryout was the culmination of a monthlong legal wrangle, following the rejection of her application by the Peabody Little League based on her sex. “I didn’t think I was doing any trailblazing at 10 years old,” she recalled in an interview in 2014 as an adult. “But the thing that threw me the most was when I went to sign up and a guy said, ‘You can’t play,’ and I said, ‘Why?’ and he said, ‘Because you’re a girl.’ I was not that smart or worldly, but I knew right then it was the most ridiculous thing I ever heard of. I remember I said, ‘But I can play, I’m really good.’”32

The ACLU worked with her parents to take her case to court and obtained a temporary restraining order. Amid extensive coverage by the Boston Globe and other newspapers in New England, the Peabody Little League resisted for weeks. In mid-May the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination ruled that the Peabody Little League was a place of public accommodation and therefore could not legally exercise sex discrimination. Cinseruli testified at the MCAD hearing that she “sincerely desired to play baseball on Little League teams” because baseball was her sport and she flatly rejected the idea of a “separate but equal girls league.”33

In addition to the newspaper coverage, Cinseruli also appeared in a television interview, which aired on Boston station WCVB, channel 5. A video of that three-minute TV interview has survived to today and is publicly available at the PBS Learning Media website.34

The May 1974 video opens with a shot of Cinseruli hitting a ball out of her hand over the heads of several boys, before she is asked if she is concerned about boys being stronger than girls. “Not really,” she replied. “A lot of kids are kind of weak but they can play okay.” She added that “most boys didn’t care” about girls playing with them in Little League “as long as they can play.” One boy interviewed vouched for Cinseruli’s baseball skills. “She’s good. She can hit good,” he said, then sheepishly admitted, “She’s almost better than me.”35

In the TV interview, Cinseruli’s mother acknowledged that the family received a lot of hate mail. “Most of the letters I couldn’t even repeat [on TV] because they were obscene, that’s just what they were,” she said. “But I feel they come from small-minded people and I just burn them, throw them away.” There were also nasty telephone calls and Cinseruli remembered that “people drove by the house and yelled things at my mother, insulting things like ‘What kind of mother are you? Put a dress on her. Teach her to type.’”36

On May 21, 1974, the board of directors of the Peabody Little League voted to accept girls, although the board reserved its right to appeal and remove the girls if they won the appeal. “Their decision will allow Janine Cinseruli, 10, and 35 other girls to join a team in one of the city’s three leagues,” the Boston Globe reported. “Cheryl Andrews, daughter of former Red Sox star Mike Andrews, is among the applicants.”37

After she won the right to play baseball in Little League, though, the newspaper reporters and cameramen continued to swarm to Peabody. “I just wanted to play baseball. The same with my parents. They knew I was a natural athlete, they just wanted me to play,” Cinseruli said, reflecting back on the experience in 2014. Because many people in Peabody hoped that she would fail, “I was always the center of attention, which I didn’t want. The town kids were supportive because they knew I was good, but I knew I had to bring it every day. There was a lot of pressure.”38

Cinseruli was not only a prolific hitter in her first year of Little League, but she was also a proficient pitcher. When she struck out 16 batters in one game, a United Press International photo appeared in newspapers throughout the Northeast region, showing Janine in her pitching form.39

“It wasn’t the greatest thing in the world at the time,” Cinseruli recalled four decades later in 2014, when the Peabody Little League enthusiastically welcomed her back to celebrate the 40th anniversary of its sex integration. “I was almost embarrassed by it for a lot of years. I shied away from it until I hit my 30s. Then I started looking at it like, ‘Hey, you know what? It’s a good thing that happened. It changed lives and it changed the way people look at girls playing sports.’”40

She also applied those baseball life lessons to her adult pursuits as a chef and restaurant owner. “I loved being on a team. I run my restaurant like a team. When things go haywire, I call a meeting and say, ‘Let’s get back to fundamentals.’ I give them pep talks all the time. I got a lot out of sports.”41

OFFICIAL END OF SEX DISCRIMINATION

On June 12, 1974, Little League Baseball capitulated on the sex issue and officially modified its position concerning female inclusion in baseball, announcing that it would “defer to the changing social climate” and adopt a policy that the “acceptance and screening of young girls, following registration procedures, should be adjudged by the local leagues and not by the international body.” There was no guaranteed acceptance of girls, though, who had to prove to local managers and coaches that they were “of equal competency in baseball skills, physical skills and other attributions scaled as a basis for team selection.”42

To mark this end of sex discrimination, The New York Times and the Associated Press immediately produced newspaper articles containing vignettes about a few of the on-the-ground foot-soldiers during the initial ten weeks of court-ordered sex integration in Spring 1974. Later that summer, similar articles appeared in two magazines targeted to a largely female readership, Ms., in its third year of publication by noted feminist Gloria Steinem, and womenSports, a startup launched that year by tennis star Billie Jean King.43

No one, though, attempted to tabulate the number of girls who played baseball on a Little League team during the 1974 season. “How many of the two million youngsters involved nationally are girls is difficult even to guess,” one New Jersey official told the New York Times in April 1975, “since sex is not listed on application blanks.” Based on anecdotal information, the number was certainly in the dozens, perhaps several hundred nationwide. This was but a tiny percentage of the two million boys that then played baseball in Little League.44

In October 1974, Congress accelerated its effort to amend the federal charter of Little League Baseball, after the New Jersey Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal of the March court decision. The amended federal charter, which changed “boys” to be “young people” and deleted reference to the “manhood” objective, was signed into law in December 1974.45

The end of active discouragement of girls from playing baseball, though, did not equate to the beginning of encouragement. While it had lost this particular legal battle, Little League Baseball planned to win the overall war by emphasizing its recently launched Little League Softball program for girls, which the organization had authorized in 1973 following the Ypsilanti, Michigan, court ruling. Under this separate-but-equal strategy, softball was not just a feminized version of the sport of baseball, but also functioned as a siphon to sway girls away from playing baseball in Little League. As McDonagh and Pappano observed in Playing with the Boys, “Creating female-only sports was viewed as a way of keeping girls out of boys’ sports” and thus maximized the male nature of the baseball program. Consistent with this patriarchal mindset, Jennifer Ring noted in Stolen Bases: Why American Girls Don’t Play Baseball that there was also no attempt to organize a separate baseball program only for girls.46

During Little League’s inaugural softball season in 1974, 50,000 girls reportedly participated, a figure later revised downward to 30,000. Either number dwarfed the estimated volume of girls in the baseball program. Softball would always be a substantial deterrent to girls participating in the baseball program. As Cohen wrote in No Girls in the Clubhouse, there was an unspoken policy “at almost every Little League sign-up, if you are female you are sent to the softball line and never told you have a choice [to play baseball]. The choice is made for you.”47

INCREASE IN FEMALE PLAYERS, 1975-2004

While the pluck and persistence of Fulle, Dickinson, Osder, and Cinseruli advanced the timing of Little League Baseball’s official acceptance of sex integration, societal change within the organization only slowly evolved to supplant its historical patriarchal attitude with a more modern sex-equality ideology. Measuring the impact of the pioneering 1974 foot-soldiers through the number of girls who played baseball in Little League during the thirty years from 1975 to 2004 is frustratingly difficult to assess.

Not only did no one count the number of female baseball players in 1974, a quarter-century later in 1999, still no one was counting. “Little League Baseball has never asked its local leagues for figures on the number of girls who have played in the baseball programs over the years,” one close observer noted in 2001. “So there is no way to determine the exact figure.” Little League Baseball could only offer vague guesstimates at the number of girls in the baseball program.48

“In 1989, it appears that resistance to having girls play on Little League teams, at least for younger age groups, has faded. But the number of girls playing hardball remains small,” Felicia Halpert reported in The New York Times. “The organization did not know how many of the 2.5 million youngsters who play baseball-youngsters from 33 countries—were girls. The group estimates, however, that there is one girl per league in the 6-to-12-year-old range” among the 7,000 leagues worldwide. The 7,000 number included girls in T-ball, structured for six-to-eight-year-old kids, which usually had the highest percentage of girls. “The numbers drop in the 9-to-12-year-old programs,” Halpert observed, “and girls are scarce in the 13-15 and 16-18 age brackets.” The estimated 7,000 girls in the baseball program paled in comparison to the 200,000 girls participating in the softball program of Little League.49

By 2004, after 30 years of sex-integrated baseball, Little League Baseball was more accepting of girls in the program, arranging for Pepe to throw the ceremonial first pitch at that year’s Little League World Series. Still, the organization tended to obfuscate its data about the female participation rate by combining softball and baseball numbers together to give the appearance of a larger number of girls in the baseball program.

In an August 2004 press release, Little League Baseball stated: “In 1974, nearly 30,000 girls signed up for the softball program. One in 57 Little Leaguers that year was a girl. Today, about one in seven Little Leaguers is a girl. Nearly 360,000 girls play in the various divisions of Little League Softball…[and] Little League estimates the number of girls currently participating in Little League Baseball programs to be about 100,000. Approximately 5 million girls have played Little League Baseball and Softball in the past 30 years.”50

The “about 100,000” statistic specified above was actually the high end of the “somewhere between 200,000 and 100,000” range of the in-house guesstimate. The median of that range—60,000 girls—might be a better representation, which would be nearly nine times the estimated 7,000 participation rate in 1989 for girls in the baseball program. The low end of the range—20,000 girls—would equate to almost tripling the 1989 approximation.51

The most reliable female-inclusion statistics released by Little League Baseball have been the number of girls playing on teams qualifying for the Little League World Series. Two girls participated in the 1980s, five girls in the 1990s, and eight girls in the 2000s. These statistics show that in this elite category of ballplayers, the ratio of girls to boys more than doubled from the 1980s to the 1990s, and then remained roughly constant in the 2000s (the World Series expanded from eight to 16 teams in 2001).52

CONCLUSION

The contribution to female inclusion in the Little League baseball program made by Jenny Fulle, Amy Dickinson, Elizabeth Osder, and Janine Cinseruli was significant. Along with dozens of other unremembered 1974 pioneers, they fought head-on an all-male organization that actively resisted the inclusion of girls under court-ordered sex integration during two and a half months in Spring 1974. Their efforts not only helped to advance the timeline for Little League Baseball to officially end sex discrimination, but also inspired young girls to leverage their pre-teen foundational skills to progress into early-teen and high-school baseball and for some to advance into the ranks of college and professional baseball during the subsequent decades.

CHARLIE BEVIS is a retired adjunct professor of English at Rivier University in Nashua, New Hampshire, and a member of SABR since 1984. He is the author of eight books on baseball history, most recently Baseball Under the Lights: The Rise of the Night Game. His research interests focus on the history of game scheduling in the pre-expansion era (notably Sunday baseball, doubleheaders, night games, and promotions) with its related impact to audience composition at the ballpark. He writes baseball from his home in Chelmsford, Massachusetts.

Another Pioneer in 1974

On June 23, 1974, Carolyn Yastrzemski was one of the first female players in the annual Father-Son Game at Fenway Park. Carolyn was the 5-year-old daughter of Red Sox star Carl Yastrzemski.

The Father-Son Game had been a ritual staple of the Red Sox promotional calendar since the inaugural event in 1958, typically held on Father’s Day or another Sunday in June. During the 1960s, Carolyn’s older brother, Mike, was often the subject of newspaper photos from the game.

Coming less than two weeks after the announcement that girls would no longer be barred from Little League, Carolyn’s appearance on the Fenway Park field was newsworthy beyond Boston. A UPI photograph of Carolyn swinging a bat, with Red Sox catcher Bob Montgomery in the background, was reproduced in newspapers across the country.

The 1974 event was rechristened the Red Sox Fathers, Sons, & Daughters Game. “Yes, women’s liberation has reached the Fenway tots,” wrote Boston Globe columnist Ernie Roberts, previewing the upcoming event, noting “there will be 13 girls among the 37 kids participating.”

Rhode Island sports columnist Elliott Stein imagined a hypothetical post-game interview with Carolyn. In the satirical column “Yazette Proves a Clutch Hitter,” Stein interspersed serious baseball questions with ones geared to a child:

Stein: How did you do today, Carolyn?

Carolyn: Hit for the cycle…single, double, triple and home run. This game is a piece of cake.

Stein: You like cake?

Carolyn: What kid doesn’t? Make mine chocolate marble and put a big scoop of butterscotch ice cream on top.

Sources

For the actual photograph, see “Carolyn Yastrzemski Batting Photograph, 1974 June 23,” National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum https://collection.baseballhall.org/PASTIME/carolyn-yastrzemski-batting-photograph-1974-june-23-0; for newspaper reproduction examples, see Manchester (CT) Journal Inquirer, June 24, 1974, 44; Shenandoah (PA) Evening Herald, June 24, 1974, p. 15; Burlington (NC) Times-News, June 24, 1974, 40. Ernie Roberts quote from “What Is [TV Channel] 38 Without Bruins?” Boston Globe, June 23, 1974, 21. Elliott Stein quote from “Yazette Proves a Clutch Hitter,” Newport (RI) Daily News, June 25, 1974, 23.

Notes

1. For history of Little League sex integration, see Tim Wiles, “Little League,” in Encyclopedia of Women and Baseball, ed. Leslie Heaphy and Mel May (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2006), 171-75; Jennifer Ring, Stolen Bases: Why American Girls Don’t Play Baseball (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 116-33; and Marilyn Cohen, No Girls in the Clubhouse: The Exclusion of Women from Baseball (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009), 137-64.

2. Lance and Robin Van Auken, Play Ball! The Story of Little League Baseball (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2001), 145, 154-56.

3. Eileen McDonagh and Laura Pappano, Playing with the Boys: Why Separate Is Not Equal in Sports (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 205; Cohen, 5-17.

4. Van Auken, 116-17; Cohen, 140-41.

5. Van Auken, 145-47.

6. For detailed analysis of the legal proceedings in National Organization of Women v. Little League Baseball, Inc., see Sarah Fields, Female Gladiators: Gender, Law, and Contact Sport in America (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005), 22-33, and Douglas Abrams, “The Twelve-Year-Old Girl’s Lawsuit That Changed America: The Continuing Impact of NOW v. Little League Baseball, Inc. at 40,” Virginia Journal of Social Policy & the Law, Winter 2012, 241-69.

7. Joan Cook, “Jersey Bids Little League Let Girls Play on Teams,” The New York Times, November 8, 1973, 51; Joseph Treaster, “Women Make Strides: On Bases and Into Mory’s,” The New York Times, March 30, 1974, 1.

8. Richard Phalon, “50 Girls Join 175 Boys at Tryout for Little League,” The New York Times, March 28, 1974, 83; Bettye Lane, “Little League Tryouts for Females, New Jersey,” Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, accessed August 28, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/ pictures/item/2013650078.

9. Rebecca Larsen, “It’s No Longer All-Boys Little League in Mill Valley,” Daily Independent Journal (San Rafael, California), April 11, 1974, 1.

10. For photograph examples, see Bakersfield Californian, April 11, 1974, 23, and Madison Capital Times, April 11, 1974, 19.

11. “Do Boys, Girls Belong on Same Diamond?” Long Beach Press-Telegram, May 24, 1973, 47; “Jenny Fulles [s/c] Appeals to President,” Corbin Times-Tribune (Kentucky), May 24, 1973, 2.

12. “Little Leaguers Seek New Park,” Daily Independent Journal (San Rafael, California), August 4, 1973, 1; Karen Peterson, “Mill Valley Little League Continues With Boys Only,” Daily Independent Journal (San Rafael, California), December 4, 1973, 1.

13. Debra Schwartz, “Oral History of Jenny Fulle,” Mill Valley Public Library, June 2017, accessed August 11, 2021. https://millvalley.pastperfectonline.com/archive/BECC1B20-F011-4644-9253-125122874547.

14. Jeanine Yeomans, “Little League Player Went to Bat for Girls,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 10, 2000, accessed September 2, 2021, https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Little-League-Player-Went-to-Bat-for-Girls-2796521.php; Neal Broverman, “A Hero’s Journey,” The Advocate, January 29, 2007, accessed September 2, 2021. https://www.advocate.com/politics/commentary/2007/01/29/heros-journey.

15. Ann Killion, “Mill Valley Little League Honors Pioneer Player Jenny Fulle,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 22, 2017, accessed September 2, 2021. https://www.sfchronicle.com/sports/article/Mill-Valley-Little-League-honors-pioneer-player-11020981.php.

16. Jean Joyce, “Some Lils Make a Hit in Li’l League,” New York Daily News, March 17, 1974, 63; Joseph Treaster, “Girls a Hit in Debut on Diamond,” The New York Times, March 25, 1974, 67.

17. Joyce.

18. Treaster; “Girls Applaud Baseball Ruling,” The New York Times, June 16, 1974, 62.

19. Susan Jennings, “‘As American as Hot Dogs, Apple Pie, and Chevrolet’: The Desegregation of Little League Baseball,” Journal of American Culture, Winter 1981, 81.

20. Jane Leavy, “Amy Dickinson: A Tomboy Who Wants Out,” womenSports, January 1977, 9-11, quoted in “Female Little Leaguer to Retire,” Lima News (Ohio), December 23, 1976, 6.

21. Felicia Halpert, “For Little League’s Girls, A Quiet Anniversary,” The New York Times, May 29, 1989, 9.

22. Yung Kim, “Donald Miller, 75: Let First Girl Play Little League Baseball in New Jersey,” Bergen County Record, May 21, 2004, 7.

23. New York Daily News, April 21, 1974, 1; “Dolls Are Playing With the Boys,” Getty Images, accessed September 14, 2021 (note: secondary sources often mistakenly cite this photo as being published on April 24 with a caption header entitled “Guys Are Playing With Dolls.”) https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/daily-news-front-page-april-21-headline-a-new-hearst-kidnap-news-photo/97292224.

24. Jean Joyce, “Score One for the Girls in Little League Opener,” New York Daily News, April 21, 1974, 3.

25. For photograph examples, see Billings Gazette (Montana), April 23, 1974, 11, and Naples Daily News (Florida), April 24, 1974, 24.

26. “Bitsy Osder, 9, first girl to play Little League baseball in New Jersey,” Getty Images, accessed August 24, 2021. https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/bitsy-osder-first-girl-to-play-little-league-baseball-in-news-photo/97263369.

27. Fred Kerber, “Are Diamonds Still a Girl’s Best Friend?” New York Daily News, March 31, 1975, 327.

28. Christopher Harper, And That’s the Way It Will Be: News and Information in a Digital World (New York: New York University Press, 1998), 43-45.

29. Charlotte Overby, “Female Who Broke Little League Gender Bar in ’74 Still Loves Baseball,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 25, 2000, 47.

30. “Six Innings With Little League Graduate Elizabeth Osder,” LittleLeague.org, March 5, 2021, accessed September 3, 2021. https://www.littleleague.org/news/six-innings-with-little-league-graduate-elizabeth-osder.

31. Marvin Pave, “Janine in Tryouts, But Peabody Little League May Disband,” Boston Globe, May 20, 1974, 5.

32. Melissa Isaacson, “The Girls Who Toppled Little League,” ESPN.com, June 24, 2014, accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.espn.com/espnw/story/_/id/11127095/small-wonders-meet-girls-toppled-little-league.

33. “Girl Ruled Eligible for Tryout,” Fitchburg Sentinel (Massachusetts), April 25, 1974, 13; Paul Langner, “2 Mass. Girls Win Little League Case,” Boston Globe, May 19, 1974, 29.

34. “Breaking the Gender Barrier in Little League, 1974,” PBS Learning Media, accessed August 23, 2021. https://mass.pbslearningmedia.org/ resource/bln13.socst.ush.now.leaguegirl/breaking-the-gender-barrier-in-little-league-1974.

35. “Breaking the Gender Barrier in Little League, 1974.”

36. Isaacson; “Breaking the Gender Barrier in Little League, 1974.”

37. “Peabody Little League Votes to Admit Girl,” Boston Globe, May 22, 1974, 4.

38. Mark Di lonno, “Little League’s 1st Girl Now a Successful Jersey Shore Chef,” New Jersey.com, May 23, 2014, accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.nj.com/news/2014/05/jersey_shore_chef_was_first_girl_little_leaguer.html.

39. For photograph examples, see Newport Daily News (Rhode Island), June 15, 1974, 15, and Olean Times Herald (New York), July 13, 1974, 21.

40. Isaacson.

41. Di Ionno.

42. “Little League Board Says Girls Can Play,” Boston Globe, June 13, 1974, 1.

43. Steven Weisman, “Those Affected the Most—Girls—Hail the Decision,” The New York Times, June 13, 1974, 26; “Most Comments Favor LL Ruling,” Newport Daily News (Rhode Island), June 13, 1974, 27; Letty Cottin Pogrebin, “Baseball Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend,” Ms., September 1974, 79-82; Maury Levy, “The Girls of Summer,” womenSports, August 1974, 36-39.

44. Joan Cook, “Girls Taking Regular Place in Line-up as Little Leagues Continue to Thrive,” The New York Times, April 7, 1975, 65.

45. Abrams, 256.

46. Van Auken, 159; McDonagh and Pappano, 220; Ring, 129.

47. “Girls’ Little League Series Set,” The New York Times, June 27, 1974, 58; Cohen, 163.

48. Van Auken, 159.

49. Halpert.

50. “Little League World Series Opening Ceremony to Mark 30th Anniversary of Decision Allowing Girls to Play,” LittleLeague.org, August 9, 2004, accessed September 12, 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/ 20110607002311/http://www.littleleague.org/media/newsarchive/05_20 04/04mariapepeopening.htm.

51. Van Auken estimate, quoted in Ring, 130.

52. “The 20 Girls Who Have Made Little League Baseball History,” LittleLeague.org, August 20, 2021, accessed September 12, 2021. https://www.littleleague.org/news/girls-who-made-little-league-base-ball-world-series-history.