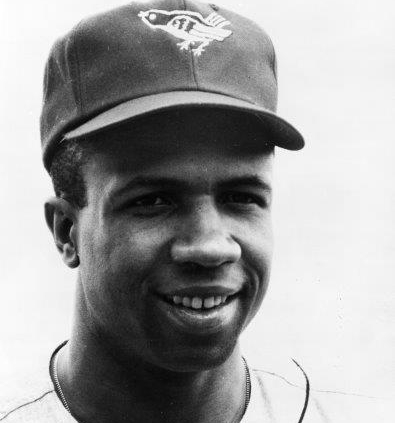

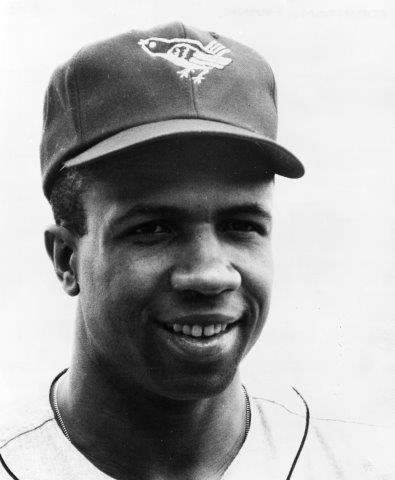

Frank Robinson and the Trade that Ignited Two(!) Dynasties

This article was written by William Schneider

This article was published in The National Pastime: A Bird’s-Eye View of Baltimore (2020)

“Bad trades are a part of baseball; I mean who can forget Frank Robinson for Milt Pappas for gosh sakes.” — Annie Savoy, Bull Durham

Outside of the 1919 sale of Babe Ruth to the Yankees, baseball trades do not often occupy a persistent niche in pop culture. As the Bull Durham quotation indicates, the December 1965 trade of Frank Robinson from the Reds to the Orioles is a notable exception.

Outside of the 1919 sale of Babe Ruth to the Yankees, baseball trades do not often occupy a persistent niche in pop culture. As the Bull Durham quotation indicates, the December 1965 trade of Frank Robinson from the Reds to the Orioles is a notable exception.

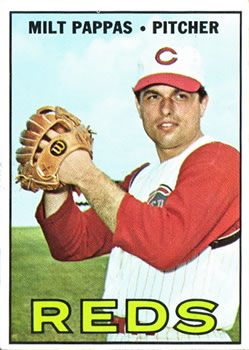

Annie doesn’t have the details quite right, though. In actuality, the Reds traded 30-year-old All Star outfielder Frank Robinson to the Orioles on December 9, 1965, for a package of players that included 26-year old starting pitcher Milt Pappas, 29-year old reliever Jack Baldschun, and 22-year old outfield prospect Dick Simpson. The trade has gone down in baseball lore as a lopsided deal that gave rise to the strong Orioles team of the late sixties and early seventies while condemning the Reds to second division status. Many articles and books have attempted to dissect the trade, and it frequently makes lists of the worst trades in baseball history.1

On the surface, the facts seem indisputable. In Robinson, the Orioles acquired a Hall of Fame outfielder in the late prime of his career. He not only won the Triple Crown in his first year in Baltimore (1966), but also was arguably the most important player on Orioles teams that won two World Series and four American League pennants across six seasons. In return, the Reds acquired a good, not great, starting pitcher (Pappas), a washed up reliever who never contributed (Baldschun), and a prospect who failed to make a major-league impact (Simpson).

However, as is often the case, there is more to the story. The “obvious” evaluation of this trade might not be the most accurate one. This article will explore an alternate viewpoint, that this trade was much closer to a “Win-Win” than is commonly perceived. In fact, the Big Red Machine might never have existed without it.

The Reds’ Perspective

Frank Robinson had played for the Reds at an elite level since entering the league in 1956. During his ten seasons (1956–65), he had accumulated 64 WAR and consistently ranked as one of the best players in the major leagues. In 1965, he delivered a slash line of .296/.386/.540 , with 33 home runs, and 113 runs batted in. These numbers were very strong, but at least in terms of conventional stats were down from his 1962 peak of .342/.421/.624, 39 homers, and 136 RBIs,.

All was not well in Reds country, though. The 1965 Reds had finished 4th in the NL standings, as their strong offense (825 runs, most in the NL) was offset by weak defense (704 runs allowed, fourth worst in the NL). Since appearing in the 1961 World Series, the Reds had won 98, 86, 92, and 89 games, but had yet to claim another NL pennant. The 1965 team had finished a distant eight games behind the National League champion Dodgers.

Moreover, the relationship between Reds owner/GM Bill DeWitt, a portion of the Reds fan base, and Frank Robinson was rocky. Frank had been arrested for possessing a firearm without a permit in Florida during Spring Training in 1961, and DeWitt had elected to let Robinson spend a night in jail without attempting to intervene. Robinson was commonly thought to resent this.2 Additionally, Robinson and the perennially cash-strapped DeWitt had annual salary squabbles for several years. Robinson had even threatened to retire in September 1963 until he received a substantial raise. Reds fans were frustrated at the team’s lack of competitiveness in 1965, and Robinson drew a great deal of their ire. Reds manager Dick Sisler had taken the unusual step of imploring fans to cease booing the outfielder at Crosley Field in August of 1965.

Bill DeWitt, under pressure to improve team pitching and in possession of a valuable asset he thought was in decline, proceeded to offer Robinson in trade to several teams. When the Orioles obtained pitcher Baldschun and outfielder Simpson in separate deals and included them with Pappas in their offer, the Reds agreed to the trade.

DeWitt had already been unsuccessful at acquiring Baldschun from the Phillies, and he liked Simpson for his speed and potential. He viewed Pappas as the incoming ace of the Reds staff, and furthermore emphasized his desire to maximize the return for Robinson while he still could. In fact, in a trade defense that is often misquoted, DeWitt described Robinson as “not a young 30,”3 and stated, “we’d rather trade a player a year too soon than a year late.”4

The Orioles Perspective

The Baltimore Orioles of the mid-1960s were a team on the rise. They had won 97 games in 1964 and 94 games in 1965, although they finished third in the American League standings both years. Those Orioles teams were pretty well balanced, having finished fourth in the majors both years in runs allowed and ninth (1964) and twelfth (1965) in runs scored. Nonetheless, Orioles General Manager Lee MacPhail thought they needed a change to break through.

In fact, per Orioles’ Farm Director Harry Dalton, the Orioles were specifically seeking an upgrade to their outfield. After the acquisition of Robinson, Dalton commented, “Oh boy, cannons at the corners!”5 With Robinson in right field, Curt Blefary in left, Brooks Robinson at third, and Boog Powell transitioning from left field to first base, the Orioles did indeed feature strong production at each of these positions. .

Pappas had been the Orioles’ best starter in 1965, and the All-Star had pitched over 200 effective innings six out of seven seasons since assuming a full time role in 1959. Nonetheless, a dearth of effective pitching was not really a concern for the Orioles. All six of the pitchers who had made 15 or more starts in 1965 had an ERA+ better than league average, 19-year old Jim Palmer had thrown 92 effective innings, and Tom Phoebus, Jim Hardin, and Eddie Watt were in the Orioles minor league pipeline. The team certainly felt that they had a pitching surplus to leverage, particularly if the payoff was someone of Robinson’s stature.

As for Baldschun and Simpson, neither had actually appeared in a game as part of the Orioles organization. Both were acquired in December 1965 deals prior to their inclusion in the Robinson trade.

The Results

From the Orioles’ perspective, the trade bore immediate fruit. Robinson came out of the gate exceptionally well in 1966, hitting for a slash line of .463/.585/.976 in April. He finished the year with 49 home runs, 122 runs, 122 runs batted in, and a batting average of .316, winning the American League’s first Triple Crown since 1956 (Mickey Mantle).

From a team perspective, the Orioles were also very successful. The team went 11-1 in April, on their way to a 97-63 overall record. They beat the Twins by nine games for the American League pennant, then proceeded to sweep the Dodgers for the first World Series title in franchise history. Robinson capped his dominant season by winning the American League Most Valuable Player award, and was named the World Series MVP as well.

The significance of Robinson’s arrival in Baltimore went beyond his stellar on-the-field contributions. Robinson’s competitive nature and leadership abilities also helped spur a normally solid team to greatness. Jim Palmer, then just starting his second big league season, noted that the Orioles prior to 1966 had always hoped to win, but, “After [Frank Robinson] got there, we expected to win.”6 Outfielder Paul Blair echoed this sentiment: “We were good before — had great defense, good pitching, decent hitting — but Frank was the key. Not only did he play great, he showed us how to be all business and get the job done.”7

What did Robinson do for an encore? He continued to slug, and made the All-Star team four of the next five seasons. Although he never won another Most Valuable Player Award, he finished third in the voting in 1969 and 1971 and garnered votes each year except for 1968.

The Orioles as a franchise, after a brief drop off in 1967, also continued their strong run. After finishing sixth in the American League standings in 1967, the Orioles climbed to second in 1968, then concluded Frank Robinson’s tenure with the team with three straight 100-win seasons, three straight American League pennants, and another World Series championship in 1970 (ironically defeating the Reds).

Meanwhile, in Cincinnati the results of the trade were not as promising. Pappas struggled out of the gate in 1966, and had a mediocre first season with the Reds (12–11 record, 4.29 ERA, allowed more hits than innings pitched, ERA+ of only 92). Jack Baldschun was a disaster as a reliever, delivering a 5.49 ERA in 57 innings. Prospect Dick Simpson was similarly disappointing , as he contributed a slash line of .238/.333/.405 in 99 plate appearances.

Meanwhile, in Cincinnati the results of the trade were not as promising. Pappas struggled out of the gate in 1966, and had a mediocre first season with the Reds (12–11 record, 4.29 ERA, allowed more hits than innings pitched, ERA+ of only 92). Jack Baldschun was a disaster as a reliever, delivering a 5.49 ERA in 57 innings. Prospect Dick Simpson was similarly disappointing , as he contributed a slash line of .238/.333/.405 in 99 plate appearances.

The Reds fortunes, as might be expected after swapping their best player for middling contributors, collapsed. Cincinnati had been in the thick of the pennant race in 1964, won 89 games in 1965 (fourth place), and in 1966 could only manage 76 wins and a seventh-place finish. The Reds’ traditionally strong offense dropped off considerably, and the pitching did not substantially improve, despite trading Robinson for pitching help.

Fan and pundit reactions were mixed immediately after the trade, but the criticism mounted throughout the season as Robinson continued to produce and the Reds continued to struggle. Reds fans did not accept the team’s declining fortunes, and Bill DeWitt took the brunt of their ire. DeWitt experienced the ignominy of being hung in effigy in downtown Cincinnati in June, his earlier good work in shepherding the Reds to the 1961 National League pennant seemingly forgotten.8

DeWitt was embattled on another front as well, as the Reds were in discussions with the city of Cincinnati for a new stadium to replace Crosley Field. DeWitt believed the Reds should move out of downtown Cincinnati to a suburban location, and as a result was unwilling to commit to an extended lease in a downtown location. When National League president Warren Giles said he would block any move out of the city, DeWitt was left with few viable alternatives.9 He sold the team to a group of local businessmen on December 5, 1966, only four days shy of a year after the trade that ultimately defined his legacy.

Milt Pappas would enjoy a strong year for the Reds in 1967, going 16-13 with a 3.35 ERA in 217 innings. But he struggled in 1968, and he was traded to the Atlanta Braves in June after delivering a 5.60 ERA in 15 games for the Reds. Jack Baldschun only appeared in nine games in 1967 and spent the rest of his time with the Reds in the minors until his 1969 release. Dick Simpson played in only 44 games and batted .259/.339/.370 in 62 plate appearances in 1967, and then was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals in the offseason.

Most conventional analyses of the “Frank Robinson trade” end here, as Robinson continued to play well for the Orioles, while the Reds had parted ways with all of the players they had acquired. Using WAR, here is how the trade stacked up:

Table 1: WAR Comparison for Directly Traded Players

|

Season |

Orioles WAR |

Reds WAR |

|

1966 |

Robinson 7.7 |

Pappas 2.4 |

|

1967 |

Robinson 5.4 |

Pappas 3.6 |

|

1968 |

Robinson 3.7 |

|

|

1969 |

Robinson 7.5 |

|

|

1970 |

Robinson 4.8 |

|

|

1971 |

Robinson 3.3 |

|

|

Orioles Total 32.4 |

Reds Total 6.0 |

Note: Baldschun and Simpson failed to contribute positive WAR to the Reds.

On the surface, this seems a convincing win for the Orioles. But although the Reds released Baldschun, Pappas and Simpson would eventually be traded for other players. A comprehensive review of the total impact of the Reds-Orioles trade not only needs to consider the contributions the players made directly to their respective teams, but also the contributions made by players that were acquired in exchange for them. Here’s where the story gets more interesting.

Milt Pappas was traded to the Atlanta Braves on June 11, 1968, along with pitcher Ted Davidson and infielder Bob Johnson, for pitcher Clay Carroll, pitcher Tony Cloninger, and shortstop Woody Woodward. At the time of the trade, Davidson was a 28-year old with a 6.23 ERA and Johnson was a 32-year old with only 17 plate appearances. It is clear the Braves were trading for Pappas.

Dick Simpson was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals on January 11, 1968, for outfielder Alex Johnson. Johnson would play two years for the Reds before he was traded in turn, along with utility man Chico Ruiz, to the California Angels for pitchers Pedro Borbon, Jim McGlothlin, and Vern Geishert.

The sum contributions of all the players acquired by the Reds need to be contrasted with Robinson’s value to the Orioles to evaluate the total on-field impact of the Robinson trade.

I chose to use Baseball-Reference.com’s Wins Above Replacement (WAR) to measure value, and I have further chosen to utilize only positive WAR and ignore negative WAR. My logic is this: the purpose of a trade is to provide assets to the team. Suboptimal deployment of those assets (such as continuing to start a below-replacement level pitcher every five days) are not necessarily reflective of the trade. I also restricted the analysis to the years 1966–71 when Robinson played for the Orioles. Going beyond that point gets increasingly complicated due to the number of players involved.

Here is how the trade stacks up considering all assets acquired by the Reds through 1971:

|

Season |

Orioles WAR |

Reds WAR |

|

|

1966 |

Robinson 7.7 |

2.4 |

Pappas 2.4 |

|

1967 |

Robinson 5.4 |

3.6 |

Pappas 3.6 |

|

1968 |

Robinson 3.7 |

6.2 |

Carroll 3.1 |

|

1969 |

Robinson 7.5 |

5.1 |

Carroll 1.2 |

|

1970 |

Robinson 4.8 |

7.8 |

Carroll 2.0 |

|

1971 |

Robinson 3.3 |

3.9 |

Carroll 1.7 |

|

Orioles Total 31.4 |

Reds Total 29.0 |

Note: Baldschun and Simpson failed to contribute positive WAR to the Reds and Pappas didn’t in 1968; Carroll played for the Reds through 1975, Borbon through 1979.

When seen through this lens, the trade was not nearly the disaster for the Reds it has widely been assumed to be. In fact, the trade was arguably a significant enabler to the launching of the “Big Red Machine” Reds team of 1970–76.

There is one more very significant consideration when evaluating this trade. The architect of the Reds of 1970–76 was legendary general manager Bob Howsam. He masterminded the 1972 trade that brought Joe Morgan to the Reds, hired Sparky Anderson, traded for George Foster, drafted Ken Griffey Sr, and made many other roster moves that were essential to creating one of baseball’s all-time best teams.

If the Robinson trade had not occurred, it is likely that Bill DeWitt would have remained in charge of the Reds, Howsam would have gone elsewhere, and baseball history might have been very different. Despite his accomplishments prior to the Robinson trade, there is nothing in his resume to indicate that he had the acumen to forge the Reds into the perennial championship-winning force they would become.

The acquisition of Frank Robinson spurred the start of the Orioles dominance. There is no doubt that with the benefit of hindsight the Orioles would make the trade again and the Reds would not. However, that 1965 trade of Frank Robinson for Milt Pappas, Jack Baldschun, and Dick Simpson ignited the great Reds team, as well.

WILLIAM SCHNEIDER has been a baseball fan since opening his first pack of baseball cards in 1974. An engineer by trade, he has a particular interest in the strategic and team-building aspects of the game. He has contributed articles to several SABR publications.

THE SECOND FRANK ROBINSON TRADE

Another bad Frank Robinson trade? The sidebar practically writes itself.

On December 6, 1971, the Orioles traded Frank Robinson and reliever Pete Richert to the Los Angeles Dodgers for a package of young players including pitcher Doyle Alexander, pitcher Bob O’Brien, catcher Sergio Robles, and outfielder Royle Stillman. Here’s the positive bWAR earned by the players in the trade (regardless of team) until the end of Robinson’s playing career in 1976:

|

Dodgers Received |

|

Orioles Received |

|

|

Frank Robinson |

11.2 |

Doyle Alexander |

3.7 |

|

Pete Richert |

2.4 |

Bob O’Brien |

0 |

|

|

|

Sergio Robles |

0 |

|

|

|

Royle Stillman |

.2 |

|

Dodgers Total |

13.6 |

Orioles Total |

3.9 |

Despite Robinson’s advanced age (he was 36 at the time of the trade), this appears to be a second trade that confirms the idea that you will not get value when trading Robinson. However, just like the 1965 Reds-Orioles trade, there is more to the story.

On June 15, 1976, the Orioles traded Doyle Alexander, Jimmy Freeman, Elrod Hendricks, Ken Holtzman, and Grant Jackson to the New York Yankees for catcher Rick Dempsey and four pitchers: Tippy Martinez, Rudy May, Scott McGregor, and Dave Pagan. The headline players were Alexander (coming off a 2.1 WAR season in 1975) and Holtzman (5-4 with a 2.86 ERA at trade time), while Hendricks (aged 35) was nearing the end of his career, Freeman was a non-prospect by that point, and Jackson would be left unprotected in the 1976 expansion draft.

In return, the Orioles received quite a haul. Dempsey, Martinez, and McGregor would all be important players in the Orioles next run of greatness (1977 to 1983), with each playing for the team through at least 1986. May kicked in 2.2 WAR from 1976–77, while Pagan failed to develop and was left unprotected in the expansion draft. Dempsey, Martinez, McGregor, and May contributed 53.8 WAR to the Orioles in total.

The Alexander trade, which was only possible because Alexander had come for Robinson, was one of the best trades in Orioles history. Unlike Bill DeWitt in 1965, Orioles general manager Frank Cashen successfully executed Branch Rickey’s “better to trade them a year early than a year late” dictum.

Sources

Photos: National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, The Topps Company

Notes

1 “For those reasons, and they are good reasons, many people in Cincinnati will always view the Robinson trade as the worst trade ever made by the Reds.” Doug Decatur, Traded: Inside the Most Lopsided Trades in Baseball History (ACTA Sports, 2009).

2 “Two thoughts stayed with him (Robinson). He didn’t know he needed a permit for the gun, but he should have known; and if Gabe Paul had still been the General Manager he would not have had to spend the night in jail.” John C. Skipper, Frank Robinson (McFarland and Company, 2015).

3 Rob Neyer, “Rob Neyer’s Book of Baseball Blunders (Simon and Schuster, Inc., 2006).

4 Robert H. Boyle, “Cincinnati’s Brain Picker,” Sports Illustrated June 13, 1966.

5 G. Richard McKelvey, The MacPhails: Baseball’s First Family of the Front Office (McFarland & Co., 2000).

6 John Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards: An Oral History of the Baltimore Orioles (Contemporary Books, 2001).

7 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards.

8 “Fans Hang DeWitt Effigy in Downtown Cincinnati,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1966.

9 Mark J. Schmetzer, Before the Machine (Cleristy Press, 2011).