From the Gashouse to the Glasshouse: Leo Durocher and the 1972–73 Houston Astros

This article was written by Jimmy Keenan

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Space Age (Houston, 2014)

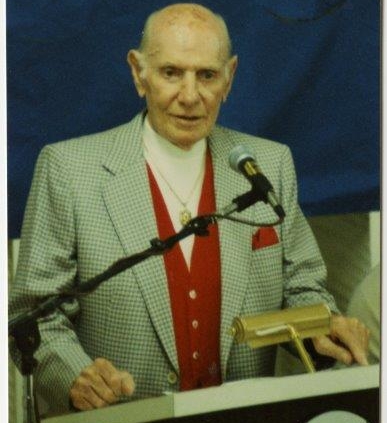

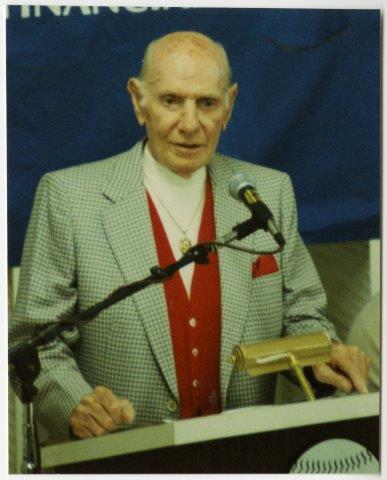

On July 23, 1972, Leo Durocher stepped down as manager of the Chicago Cubs. Durocher had taken over an underachieving Cubs team in 1966 and in two years, turned them into a contender, but Durocher’s abrasive style of managing alienated many of his players. There were also run-ins with umpires, health problems, and several unexcused absences that led to a “Dump Durocher” movement by the Chicago fans.

On July 23, 1972, Leo Durocher stepped down as manager of the Chicago Cubs. Durocher had taken over an underachieving Cubs team in 1966 and in two years, turned them into a contender, but Durocher’s abrasive style of managing alienated many of his players. There were also run-ins with umpires, health problems, and several unexcused absences that led to a “Dump Durocher” movement by the Chicago fans.

After his 1972 ouster, Leo and his wife Lynne began making arrangements for a USO junket to the Far East. The Durochers received their travel vaccines, updated their passports, and were planning their itinerary. Around midnight on the evening of August 25–26 their plans changed when Durocher received an unexpected telephone call from Spec Richardson, a longtime friend and the general manager of the Houston Astros. Richardson had just fired manager Harry Walker and was calling to see if Durocher was interested in the job. Leo politely declined and hung up. Richardson called back five times that night before Durocher finally said yes.

When asked about hiring the 67-year-old Durocher, Richardson told the United Press International, “Leo’s age didn’t bother me, I thought our club ought to be doing better, and Leo might fire ’em up.”1

The Astros’ new skipper was a light-hitting infielder who played for the Yankees, Reds, Cardinals, and Dodgers. As a player, he won a World Series with the New York Yankees in 1928 and another with the St. Louis Cardinals Gashouse Gang in 1934. Durocher took over as player-manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1939. He remained at the helm until July 1948 when he left to manage the New York Giants. In 1947, he was suspended for the entire season by baseball commissioner “Happy” Chandler for several reasons including allegedly consorting with known gamblers. Durocher managed the Giants 1948–55, winning two National League pennants and a World Series. He was named The Sporting News manager of the year three times. He later coached the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Astros GM Harold B. “Spec” Richardson began his career in baseball in 1946 as the concessions manager for the Columbus Cardinals in the Class A South Atlantic League. He became the team’s business manager in 1949. In 1953, Richardson was hired as the general manager of the Jacksonville Braves, the Milwaukee Braves affiliate in the South Atlantic League. Jacksonville finished in first place three times under Richardson’s guidance. In December 1959, Richardson was named GM of the minor-league Houston Buffaloes. In October 1961, he became the business manager of Houston’s fledgling National League franchise, the Colt 45s. In 1967, Richardson was promoted to GM of the renamed Astros. The press occasionally referred to the Astros as the “Glasshouse Gang,” alluding to the skylights in the Astrodome roof.

With Durocher at the helm, Houston reeled off five straight victories. The club’s new skipper predicted that his Astros would catch the first-place Cincinnati Reds, who were 8 games up in the standings when he took over. It didn’t happen, and on September 22 the Reds defeated the Astros, 4–3, to clinch the National League West Division. That same night, Durocher pulled pitcher Larry Dierker in the first inning after he gave up two earned runs. Dierker was visibly upset over his removal, which angered Durocher. After the game Durocher told The Sporting News, “I told my players that I will not show them up on the field or in the dugout and that I expect the same of them.”2

Durocher benched Dierker for the remainder of the season but insisted there would be no future repercussions over the incident.

Houston finished the 1972 campaign 16–15 under Durocher. When the season ended, Durocher fired coaches Salty Parker and Buddy Hancken. They were replaced by Preston Gomez and Grady Hatton. Gomez, an infielder with the Washington Nationals in 1944, had been let go by the San Diego Padres after managing the team 1969–72. Hatton, another former major league infielder (1946–60), had worked for the Houston organization in a number of high profile positions, including manager, since 1961. Gomez was Durocher’s choice but Hatton was Richardson’s man, placed to monitor the unpredictable Durocher.

Things got off to a bad start in January when Dierker underwent surgery to remove a calcium deposit at the base of the index finger on his pitching hand. His recovery was delayed when the sutures used in the procedure grew back into his hand, requiring a second surgery.

The Astros held their spring training at Cocoa, Florida. The 52-acre site had four practice fields and a 5,000 seat stadium. The complex was located in the backwoods, five miles inland from the town of Cocoa. Most of the baseball writers who covered spring training normally by-passed the facility, but now that Durocher was managing the Astros, the place was a hotbed of activity.

In early March, Marvin Miller, the Executive Director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, began visiting spring training sites to brief the players on the new three-year deal with the owners. According to Miller these meetings were legally necessary in order to ratify the agreement. Spec Richardson was livid when he learned that Miller scheduled the Astros meeting on March 12 before a game with the Texas Rangers at Pompano, 165 miles away.

On March 11, the Astros played the Minnesota Twins at Orlando in a game that was televised in Houston. Durocher wanted the Astros fans to get a good look at his team so he played his starters all nine innings. When Durocher posted the list for the traveling squad that was going to Pompano the next morning it was made up of nearly all non-starters. He put up a second list for any of his regulars who wanted to take another bus that would leave an hour earlier (6:30AM) in order to make Miller’s 10:30AM meeting. A couple of players volunteered to take the early bus then changed their mind when none of the other regulars signed up.3 It would’ve been a seven-hour round-trip bus ride. Richardson felt that Miller could’ve come to the Astros spring training facility or met the club a few days earlier at Daytona Beach, only sixty miles away.

The Astros arrived in Pompano around 10:45AM and joined the Rangers who were meeting with Miller in center field. The players had listened to Miller for about 30 minutes when Durocher came out and broke up the gathering, saying,“Come on, let’s go, it’s 11:30. We hit in ten minutes.”4 Miller and his attorney Dick Moss were furious, saying the Astros violated the agreement, which specified that each team be available for a 90-minute meeting.

This wasn’t the first time that Durocher ran afoul of organized labor. In 1936, the Central Trades and Labor Union threatened to boycott St. Louis Cardinals games after Durocher sided with his wife when she crossed the picket line during a garment workers strike. He later apologized and the boycott was lifted. In the spring of 1946, Durocher and Branch Rickey banned union organizer Robert Murphy, founder of the ill-fated American Baseball Guild, from Dodgers camp.

Durocher’s actions that day in Pompano drew the ire of National League president “Chub” Feeney, who fined him $250. Durocher said he would retire before he’d pay the fine. Richardson backed his manager, telling The Sporting News, “Leo was right. Thirty-eight ballplayers, every man on our under-control-roster, have said that they didn’t want to meet with Marvin Miller—not in Pompano. That’s a heckuva blow to him. I think his pride is hurt. I think Durocher is the only man in baseball with the guts to do this and I think he is right.”5

In order to keep the peace, a check was sent to Feeney, but in his autobiography, Nice Guys Finish Last, Durocher asserts it was never cashed.

Excitement was growing in Houston over the upcoming season thanks in part to the slogan “1973—The Year of The Astros” that was posted on billboards all over the city. Durocher felt that his infield of Lee May (1B), Tommy Helms (2B), Roger Metzger (SS), and Doug Rader (3B) was the best in the National League. The outfield was set with Cesar Cedeño and Jim Wynn. Newly acquired Tommie Agee would fill the final outfield spot if Bob Watson was able to make the transition to catcher. If not, Watson would play the outfield and Agee would come off the bench. The other catching candidates were John Edwards, Larry Howard, Cliff Johnson, and Skip Jutze. There were a number of reserves who would see action including Bob Gallagher, Hector Torres, Jimmy Stewart, and Jesus Alou.

Durocher was a proponent of the four-man rotation. With Dierker sidelined, he went with Dave Roberts, Ken Forsch, Don Wilson, and Jerry Reuss. The rest of the Astros staff consisted of Fred Gladding, Tom Griffin, Jim Ray, Jim Crawford, Jim York, Mike Cosgrove, and Doug Konieczny. Juan Pizarro and Cecil Upshaw were acquired during the season and rookie J.R. Richard was called up later in the year.

Durocher told the Associated Press,“We have one of the best balanced ballclubs I have ever seen. We are set at seven positions and there aren’t any players in the National League who can beat out our players at their positions even if they played for us. I’ve got power, I’ve got speed and I have a good defense. What I’m looking for is pitching. That’s what we’re looking for more than anything this spring is pitching. I know the arms are there it’s just the question of finding the right ones. I know our pitching wasn’t what it is was supposed to have been last year but I know these pitchers and I’m confident that they are much better than what they showed.”6

In a move that caught many of the Astros by surprise, Durocher fired pitching coach Jim Owens the day before the season opener. He filled the vacancy on the staff with former Astro Bob Lillis. Richardson spoke to the Associated Press about the move, “Durocher said he wasn’t completely happy with the pitching staff and thought a change was in order.”7

Houston started out the 1973 season playing good ball, posting a 14–10 record in April and 15–12 in May. Unfortunately, it was all downhill from there. The same problems that plagued Durocher in Chicago arose again in Houston. Durocher wrote in his book Nice Guys Finish Last that he tried a new approach with the Astros: The dictator would become one of the boys. He’d play cards with the guys and share stories in an attempt to gain their friendship. This new tactic failed miserably. He felt that it undermined his authority in the clubhouse, causing him to lose the respect of the team. Durocher lamented that the modern players’ high salaries gave them too much leverage with management. He also noted that Richardson was too close to the players, who complained to him whenever they felt slighted.

Dierker and Durocher were never on the same page. Dierker developed shoulder problems when he returned to the team and was used sparingly. He would later tell the Associated Press what is was like playing for Durocher. “I did not say anything to the press or make any complaint about it. But frankly I was afraid of what that guy in there would do. You couldn’t tell what he’d do. He might have given me the ball and told me to pitch and left me in there until my arm fell off. I know myself well enough to know that if he kept giving me the ball I’d take it. My arm had been hurt seriously a couple of times and I did not want to jeopardize my whole future in the hands of Durocher. I figured it would be better to sit and wait and hope he was fired or that I was traded.”8

Durocher had a well-publicized argument with pitcher Don Wilson on the team bus. Wilson was fined $300 and later apologized. When comparing Durocher to his eventual successor Preston Gomez, Wilson told The Sporting News, “I like what I’ve seen of [Gomez]. He doesn’t do things on impulse or superstition, like the last guy. Every move he makes is on sound judgment. Preston thinks about winning. He’s not like Leo who just thinks about getting his name in the paper.”9

Pitcher Jerry Reuss, who called Durocher “the dummy we had (in the dugout)” got into a heated argument with his manager after he was removed in the fourth inning while leading 7–3 with two outs and two men on base.10 Durocher explained to Reuss why he took him out, saying, “I didn’t want the married men in the infield killed. They were hitting bullets off you.”11 Later in the season, Reuss was getting hit hard again. This time Durocher gave him a chance to work out of the jam. Unable to stop the rally, he was finally taken out. When Reuss sat down in the dugout he looked at Durocher and asked, “What the hell took you so long?”12

Durocher also had problems with catchers Larry Howard and Skip Jutze. Howard was traded to the Braves after incurring Durocher’s wrath for lackadaisical play. Jutze briefly quit the Houston organization after refusing a minor-league assignment. He would eventually report and was called up in May 1973.

When Durocher joined the Astros he compared Cesar Cedeño to a young Willie Mays. Cedeño put together a fine statistical season in 1973 (.320 BA, 25 HR, 70 RBIs). However, his inability to play through injuries coupled with his unwillingness to take coaching advice was a source of consternation for both Durocher and Richardson.

The experiment of using Bob Watson behind the plate didn’t pan out, which relegated Tommie Agee to a back-up role. An ankle injury affected Agee’s overall play and he never got on track. He was traded to the Cardinals in August. Watson (.312 BA, 16 HR, 94 RBIs) went on to have an excellent year.

No season would be complete without Durocher battling with umpires. On May 15 the Astros played the Braves at the Astrodome. The fireworks started when umpire Bruce Froemming ruled that Hector Torres didn’t touch second base while turning a double play. The second part of the controversy occurred when first baseman Lee May, thinking the inning was over, flipped the ball to umpire Paul Pryor. With the Braves Dusty Baker running around the bases, Pryor dropped the ball on the ground. Durocher accused Pryor of throwing the ball away from May, allowing Baker to score. Because of Froemming’s call and Pryor’s actions, Durocher informed the umpires that he was playing the game under protest. Richardson, still upset over a disputed home run call by Augie Donatelli two days earlier, instructed the Astrodome scoreboard operator to post the following message,“Manager Leo Durocher has announced the game will be played under protest. Umpires Froemming and Donatelli have blown two decisions in the last three days.” Richardson was fined $300 by the league office but remained unrepentant. On June 26, Durocher was ejected and fined $150 after he kicked a batting helmet into the shins of umpire John Kibler while arguing a call.

Durocher also fell ill twice during the year with diverticulitis of the colon. He was hospitalized in late April through early May and again in August. The team went 16–5 under interim manager Preston Gomez during his absence.

The Astros finished the 1973 season in fourth place with a record of 82–80. Richardson summed up the year in an interview with The Sporting News: “This team is a lot better than it has shown in the standings. They’ve not lived up to their potential. They’ve been a big disappointment to me. The bullpen has been here a long time… the whole pitching staff practically for that matter. Wilson, Dierker, Ray and Griffin… and pitching has been a problem. The staff has a good year one year and is lousy the next. I expect to make changes. You can take every position on the field except shortstop (Roger Metzger) and second base (Tommy Helms) and have something critical to say about it. Wynn started good and went into a long slump and has never gotten out of it. Cedeño got hurt and stayed hurt the rest of the year. He can’t play with any pain. Despite his statistics its been a disappointing year for Cedeño in my book. He hasn’t done all we expected of him. Lee May? He’ll end up with around 30 home runs and 100 RBIs but that doesn’t give a true picture. He started out slow—just like Rader—and didn’t do much early in the year. Watson dropped off late. Metzger is probably the best player I’ve had all year. As far as consistency is concerned, if I was voting for the most valuable player on our team, I’d vote for Metzger.”13

Richardson remained with the Astros through the 1975 season. From there he moved on to the San Francisco Giants where he was named executive of the year in 1978. In 1994, he was inducted into the South Atlantic League Hall of Fame.

Late in the year, Durocher informed some of the veterans on the club that he was retiring at the end of the season. He wrote in Nice Guys Finish Last, “It isn’t the game I used to know. In the first place there are the players. They’re a different breed. They’ve got a union, headed by Marvin Miller, and they’re carting their money off in bushel baskets. You can’t tell them what to do. They have to be consulted; they want to know why. Not how but why. The battle cry of today’s player is: I don’t have to.”14

Some Astros never respected Durocher or his past accomplishments and felt he was a relic from an era that was no longer relevant. On October 1, 1973, Durocher resigned, telling the United Press International, “Baseball has been 45 years of a wonderful life. But I have a lot of things to do now. I’m going out to Palm Springs and I’m going to tee it up and play a lot of golf.”15

In 1976, the Taiheiyo Club Lions of the Japanese Pacific League offered him a reported $150,000 to manage the team for one season.16 A slow recovery from heart surgery along with a recent bout of pneumonia precluded him from taking the job. Leo Durocher never managed again, passing away in 1991. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame three years later.

JIMMY KEENAN has been a SABR member since 2001. His grandfather Jimmy Lyston and other family members were all professional baseball players. A frequent contributor to SABR publications, Keenan is the author of “The Lystons: A Story of One Baltimore Family and Our National Pastime” and a 2012 inductee into Baltimore’s Boys of Summer Hall of Fame.

Sources

Online

Baseball-almanac.com, www.baseball-Almanac.com/players/awards.php?p=durocle01, accessed December 12, 2013.

Baseball-reference.com, www.baseball-reference.com/managers/durocle01.shtml, accessed January 10, 2014.

The Official Site of the Class A South Atlantic League www.milb.com/content/page.jsp?sid=l116&ymd=20080228&content_id=352571&vkey=league3, accessed December 23, 2013.

Books

Eskenazi, Gerald. The Lip: A Biography of Leo Durocher (New York: William Morrow, 1993.

Durocher, Leo with Ed Linn. Nice Guys Finish Last (New York: Simon & Schuster), 1975.

Wynn, Jimmy and Bill McCurdy. Toy Cannon: The Autobiography of Jimmy Wynn (Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland and Company 2010).

Lowenfish, Lee. Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 2007).

Newspapers

Bend (Oregon) Bulletin

Lewiston (Maine) Daily News

Miami News

Montreal Gazette

(Connecticut) Morning Record

Nashua (New York) Telegraph

Sumter (South Carolina) Daily Item

The Sporting News

(North Carolina) Times-News

Tuscaloosa News

(Texas) Victoria-Advocate

Notes

1. Edwin Shrake,“I Talk Real Polite And Nice,” Sports Illustrated, August 13, 1973 volume 39, issue number 7.

2. John Wilson,“A Durocher-Dierker Feud?” The Sporting News, October 14, 1972, 13.

3. The Sporting News gives two different accounts of which players volunteered to take the early bus to Pompano. One account listed Larry Dierker, Jerry Reuss and Cliff Johnson. The other lists Dierker and Cesar Cedeño. Dierker reportedly wanted to speak with Marvin Miller about resigning as the team’s union representative. Cedeño wanted to visit his friend Rico Carty who was playing for the Rangers. There were no reasons given as to why Johnson and Reuss wanted to make the trip. (Joe Heiling,“Here Comes Leo- Quick Astros Exit,” The Sporting News, March 31,1973, 30.)

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. “Durocher Picks Excellent Year for Well-Balanced Astros,” Associated Press. Quote excerpted from the (Connecticut) Morning Record, March 13, 1973, 9.

7. Hersche L. Nissenson,“Durocher Shuffles Staff, Fires Owens,” Nashua (New York) Telegraph, April 14, 1973, 14.

8. Joe Heiling, “Dierker Ready to Go, Jubilant Astros Claim,” The Sporting News, February 23 1973, 27.

9. Joe Heiling,“Low Key Gomez Strikes High Note with Wilson,” The Sporting News, January 5, 1974, 27.

10. “Reuss Criticizes Trade–Durocher,” Associated Press, Quote excerpted from the Victoria (Texas) Advocate November 3, 1973, 3.

11. Leo Durocher and Ed Linn.“The Old Way is Dead,” Sports Illustrated April 28, 1975 volume 42, issue 17.

12. Ibid.

13. Joe Heiling,“Faded Astros Face Pruning by Fed-Up GM Richardson,” The Sporting News, September 22, 1973, 17.

14. Leo Durocher with Ed Linn. Nice Guys Finish Last (New York: Simon & Schuster), 1975. 410.

15. “Durocher Resigns, Astros Hire Gomez”, United Press International, Quote excerpted from the Montreal Gazette, October 2,1973, 25.

16. The Sporting News of January 3, 1976 (7) listed Durocher’s salary offer from the Taiheiyo Club Lions as $150,000. The Sporting News of April 3, 1976 (47) noted the salary offer had risen to $220,000. This article notes that Durocher signed the contract but it was later voided due to his health issues.