Gentle Black Giants — Negro Leaguers in Japan: 1927 Philadelphia Royal Giants Tour

This article was written by Bill Staples Jr.

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

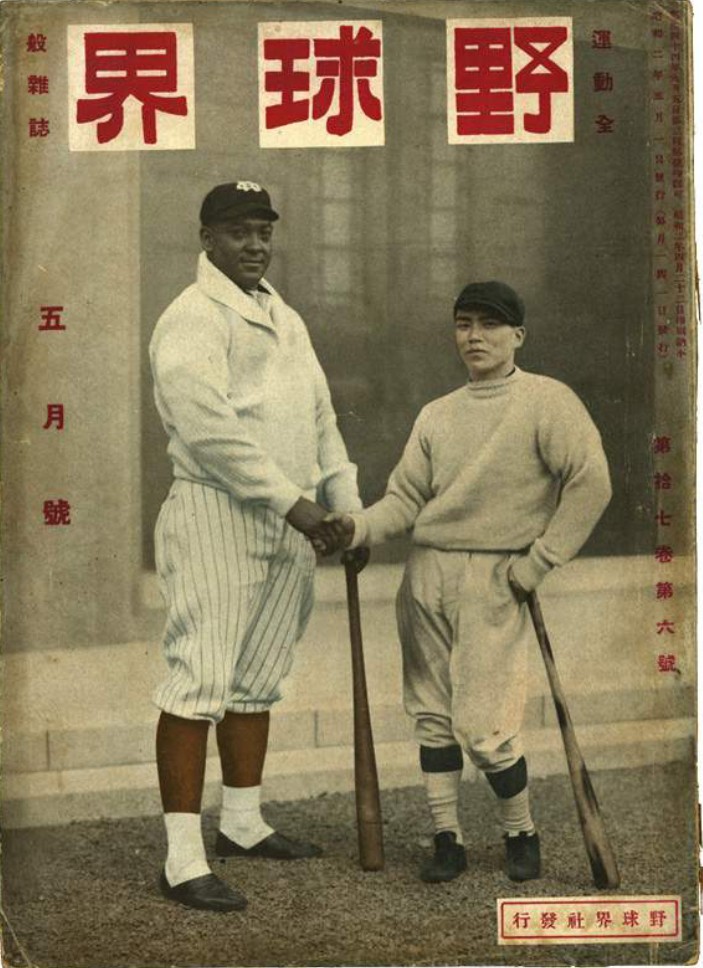

Cover of the May 1927 issue of Yakyukai depicting O’Neal Pullen and Shinji Hamazaki (Rob Fitts Collection)

Kazuo Sayama, baseball historian, author, and member of the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame (enshrined in 2021), states with great passion and conviction that had it not been for the tours of the Negro Leagues’ all-star Philadelphia Royal Giants in 1927 and the early 1930s, a professional baseball league in Japan would not have started when it did, in 1936.

“There is no denying that the major leaguers’ visits were the far bigger incitement to the birth of our professional league. We yearned for better skill in the game,” said Sayama. “But if we had seen only the major leaguers, we might have been discouraged and disillusioned by our poor showing. What saved us was the tours of the Philadelphia Royal Giants, whose visits gave Japanese players confidence and hope.”1

Sayama first learned about the Royal Giants as a member of the Society for American Baseball Research in the early 1980s. Like the fictional Ray Kinsella, who heard voices telling him to build a baseball diamond in the middle of his cornfield, Sayama was a man possessed during much of the early part of that decade, researching and documenting the history of the Royal Giants.2

Also fueled by the desire to honor the Black US soldiers who coached him as a boy in Yokohama during the post-World War II occupation, Sayama hit the library stacks and microfiche in the archives and traveled the world interviewing anyone with a connection to the team.3

In doing so he discovered that the Negro Leaguers had visited Japan just as many times as the famous All-American major leaguers during the 1920s and 1930s (three times each), yet historians on both sides of the Pacific had all but forgotten the Philadelphia Royal Giants.

“It is unfair that no words of gratitude have been spoken by the Japanese to this team,” lamented Sayama.4 He changed that by publishing his seminal work in Japan in 1985, Kuroki Yasashiki Jaiantsu, which details the events of their tours and the impact the team made while in Japan. Best of all, he captured firsthand accounts from many Japanese players who competed against the all-Black team, men who were so impressed and impacted by the touring players’ unique blend of baseball skill and human kindness that it inspired a term of endearment from Japanese players—with gratitude and fondness in their hearts, they referred to their guests as “Gentle Black Giants.”

The Philadelphia Royal Giants were indeed the first all-Black team to play in Japan, but their games did not mark the first time for Black and Japanese baseball teams to compete head-to-head on a diamond. The history of games between ballplayers of Japanese ancestry and Black teams dates to at least May 19, 1908, when the Issei (first-generation Japanese in America) Mikado’s Japanese Base Ball Team from Denver played the Lexington (Missouri) Tigers. But earlier undocumented games probably took place.5 After that contest, and long before the Royal Giants set sail for Japan in 1927, dozens of such games occurred. Of those matchups, the following are noteworthy for their ties to the Royal Giants:

- December 4, 1915, Honolulu—Chinese Travelers vs. 25th Infantry Wreckers. Outfielder Andy Yamashiro, the first Japanese American to sign a contract in Organized Baseball (in 1917), honed his skills competing in Hawaii as a member of the mixed-Asian Chinese Travelers (comprising Chinese, Japanese and Hawaiian players) against top-Black talent like Wilbur “Bullet” Rogan, Robert Fagen, Dobie Moore, and Oscar “Heavy” Johnson, all members of a military team known as the 25th Infantry Wreckers.6 Fagen and Rogan later barnstormed across the Pacific as members of the Royal Giants.7 Yamashiro managed the Hawaii Asahi ballclub that competed against the Royal Giants in 1927.

- June 2, 1924, Washington, DC—Meiji University vs. Howard University. This game marked the first time a visiting team from Japan defeated an all-Black team. The Meiji roster included Saburo Yokoza- wa, a second baseman who in 1927 would compete against the Royal Giants in Japan as a member of the Daimai club.8

- September 6, 1925, Los Angeles—Fresno Athletic Club vs. L.A. White Sox. Over 3,000 fans packed into White Sox Park to witness Kenichi Zenimura’s Japanese nine defeat Lon Goodwin’s ballclub, 5-4. This encounter led to a rematch a year later, setting the wheels in motion for Goodwin to take his ballclub to Japan in 1927.9

Plans to take a Negro League team to Japan were proposed in the early 1920s but failed to materialize. On February 21, 1921, the Chicago Defender wrote, “A syndicate of Japanese here representing authorities at Waseda, Tokio [sic], Yokohama and Kobe Universities in Japan, announced last week that they are eager to take an all-star baseball team made up of members of the Race to their fatherland next fall for a series of games. A large sum of money has been deposited in a local bank to defray all expenses, which guarantees the proposition is in good faith.”10

The goals of the planned 1921 tour were ambitious. “The spokesman further stated that … the main idea is to put baseball on a firm foundation, and to have the interest manifested in the pastime [in Japan] as in this country [United States].”11 The stars never aligned for that Negro Leagues all-star tour of Japan to occur. That would take another five years.

As a follow-up to their thriller in 1925, Lon Goodwin and Zenimura scheduled a rematch for the L.A. White Sox and the Fresno Athletic Club (FAC), a doubleheader in Fresno over the Fourth of July weekend, 1926. Zenimura’s team, bolstered by a few non-Japanese players, called themselves the Fresno All-Stars. They defeated the L.A. White Sox in both games, 9-4 and 4-3.12

Off the field, it was customary for Zeni to invite visiting teams to social outings the night before a game. Thus, the Fourth of July weekend created the opportunity for Zenimura and Goodwin to discuss the possibility of parallel tours of Japan in the future.

Born in Hiroshima, Japan, Zenimura had visited his motherland as a baseball ambassador a few times prior to 1926. In 1921-22 he traveled to Hiroshima, where he coached baseball at Koryo High School. In 1924 he returned with his FAC, completing a successful 46-day tour of Japan, playing 28 games and finishing with a 21-7 record.13

By the summer of 1926, Zeni already had plans in place for another tour of Japan for the following spring. He had learned valuable lessons during the first tour and shared them with the Fresno press. “In Japan it doesn’t pay to win a game [by] a far margin. If we do then there won’t be any crowd coming to the next game … One day we played against the pro team of Osaka which is known as Diamonds and in our first game we defeated them by a score of 11-2. In this game quite a many fans [sic] came to see the outcome but on the following day with the same teams there was hardly any people in the stand[s]. For this reason, it is hard for the visiting team to play a game in Japan.”14

Months later, Goodwin received a chance to put Zenimura’s advice into practice. On December 21, approximately five months after the series in Fresno, the Nippu Jiji reported that Goodwin’s L.A. White Sox—not the Philadelphia Royal Giants—had received an invitation to tour Japan from officials in Fukuoka City, one of the locations where the FAC competed during the 1924 tour.15

To help plan his team’s tour, Goodwin turned to Joji “George” Irie, a Japanese native who was known in Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo area as an active sports and entertainment manager. The Japanese Who’s Who in California described Irie as a man “with an impressive mien and stature of such dignity,” adding that professionally he was “agile and enthusiastic, quick to weigh the interests, and daring enough to take any means to achieve his ends; his inscrutable ability defies imagination for his swiftness and vehemence.”16

Bom in 1885 in the Yamaguchi Prefecture of Japan, Irie arrived in the United States at age 20 and went east to study law at the University of Pennsylvania. He returned to California in the early 1920s and worked as a translator in sectors that served the legal needs of the Japanese immigrant community. He eventually caught the attention of Yoshiaki Yasuda, president of the Japan-US Film Exchange Company, who hired him to be the organization’s secretary. In that role, he helped Yasuda oversee the world of entertainment in LA’s Little Tokyo, including sumo, kembu (Japanese sword-fight theater), baseball, and gambling.17 In 1935, several years after Irie’s involvement in the Royal Giants ended, Yasuda was assassinated by the yakuza (Japanese mob). According to Professor Kyoko Yoshida, this murder, coupled with the photos of the Royal Giants posing with sumo and other figures of Japan’s underworld, suggest that Irie’s work might have placed himself, Goodwin, and the Royal Giants, in close proximity to the Japanese mob during the 1927 tour.18

Before the team departed for Japan, Irie sent officials there an advance roster of the players slated to join the tour. The names reflected on the list included all of the members of the Philadelphia Royal Giants entry in the 1926-1927 California Winter League: O’Neal Pullen, C; Frank Duncan, 1B-C; Newt Allen, 2B; Newt Joseph, 3B; Willie Wells, SS; James Raleigh “Biz” Mackey, SS, P, C; Carroll “Dink” Mothell, Utility; Norman “Turkey” Steames, OF; Herbert “Rap” Dixon, OF; Crush Holloway, OF; Andy Cooper, P; Bill Foster, P; George Harney, P; Wilbur “Bullet Joe” Rogan, P-OF.19

Of those 14 players, Goodwin could persuade only five to take him up on his offer to tour Japan—Pullen, Duncan, Mackey, Dixon, and Cooper. Goodwin had fallen out of favor with organized Negro Leagues baseball in the East, and delivered a parting shot when the team sailed off for Japan. “The National Negro and the Eastern Leagues are cutting salaries to a place where a ballplayer is not fairly paid for services rendered,” Goodwin told the press.20

To fill out the roster, Goodwin recruited players from his semipro team, the L.A. White Sox. Thus, when the ship pulled away from Los Angeles on March 9, 1927, the revamped Philadelphia Royal Giants roster comprised O’Neal Pullen, C; Frank Duncan, 1B-C; Robert Fagen, 2B; Jesse Walker, 3B; James Raleigh “Biz” Mackey, SS, P, C; John Riddle, 3B-SS; Julius “Junior” Green, OF; Herbert “Rap” Dixon, OF; Joe Cade, OF; Andy Cooper, P; Ajay Johnson, P; Eugene Tucker, P; Alexander “Slowtime” Evans, P; Lonnie Goodwin, manager; and George Irie, promoter/ interpreter.

As a result of the roster change, the team chemistry changed too. For the five members of the Philadelphia Royal Giants of the California Winter League, baseball was their full-time profession. For the others, it was a passion and an extracurricular activity outside of their day jobs. For example, Ajay Johnson was a police officer who would later become one of the first Black lieutenants in LAPD history. John Riddle attended the University of Southern California, where he also played football and earned a degree in architecture. Joe Cade was a US Navy Veteran and firefighter, who became a favorite in Hawaii to fans with military ties. The captain of the team was Mackey, whose ability to play multiple positions combined with his laid-back demeanor and patience in teaching others made him the perfect fit as a team leader on a goodwill tour.21

After a rocky 5,497-mile, 20-day journey crossing the Pacific Ocean, the Royal Giants arrived in Yokohama on March 29. The team spent two days working out their sea legs and preparing to do battle against the best college, amateur, and industrial leagues teams Japan had to offer. Their first game, against the Mita Club, was scheduled for April l.22

Coverage by Yakyukai (Baseball World) magazine revealed that the Japanese media misunderstood the ethnicity of their dark-skinned guests. “The ‚ÄòPhiladelphia Royal Giants’ sounds like a magnificent name. This team of American Indians became very famous. …”23

Setting aside the mix-up on players’ racial backgrounds, Yakyukai detailed the events of the first game: “The stadium was jam-packed because people had heard that the black players had the reputation of being a powerful team. While the Mita Club were practicing on the field, the Royal Giants entered with big smiles and were welcomed by loud applause from the crowd. They wore off-white jerseys just like the Sundai uniform. The Royal Giants started to entertain the fans. They began light warm-ups and batting practice. They hit very well for sure. All their hits looked like line drives. They were well-built and physically much stronger than Mita’s batters. During fielding practice, the shortstop, Mackey, showed off his strong arm. The speed of the ball was like a bullet. The first baseman (Duncan) also performed well with his slick glove work. Both Mackey and the first baseman shined among the infielders. However, some flaws in their fielding skills were noticeable. If the Japanese team were to stand a chance, they needed to take advantage of the Giants’ weak points. … There were two umpires, Ikeda and Oki. The game started with the Mita going to bat first. The pitchers were Takeo Nagai and Cooper.”24

After Tokyo Mayor Hiromichi Nishikubo tossed the first ceremonial pitch, the Royal Giants proceeded to win their first game in Japan, a 2-0 victory over the Mita Club.25

The first Japanese player to bat against the Royal Giants was future Japanese Hall of Famer Shinji Hamazaki, who struck out against Cooper’s fastball. The lefty forced the next two batters, Eiji Sugai and Nagai, to ground out. Three up, three down.26

The Royal Giants came out swinging, with the leadoff hitter Frank Duncan lining a single to center field. He broke for second base as Robert Fagen, the number-two hitter, successfully executed the hit-and- run by placing a groundball to the opposite side of the field, between first and second. Duncan scored the first run of the game—and of the tour.27

Mita threatened to score in the second, with a leadoff hit by Eiichi Nomura to right-center. Michimaro Ono then hit a slow roller back to the pitcher Cooper, who attempted to get the force out at second. The speedy Nomura beat the throw, resulting in runners on first and second. With two on and no outs, catcher O’Neal Pullen fired a bullet to second base, catching Nomura leaning too far toward third. The next batter, Kiyoshi Okada, grounded to shortstop Mackey for a 6-4-3 inning-ending double play.28

The first inning set the tone that defense would be the deciding factor in this game. In the bottom of the second inning, Hamazaki dazzled fans with an exciting play in the outfield. After Mackey reached first on a walk, Cade hit a long drive to the right-center gap. Hamazaki sprinted and reached out to catch the ball just before it hit the ground. The hero quickly became the goat. On the next play Hamazaki mis- played Slowtime Evans’s fly ball, allowing it to roll to the fence and for Mackey to score from first.29

The offensive attack of both clubs was held in check from the third inning on. Mita pitcher Nagai took control of the game and limited the damage by the Royal Giants, who continued to mount rallies, but failed to convert any opportunities to score. Cooper pitched a three-hit shutout and allowed no walks.

The low-scoring game caught the attention of the Japanese fans, media, and opposing teams who were in attendance to scout the Royal Giants in preparation for future games. Observers noted that “the Royal Giants’ batting was not as strong as expected … [and] left an impression of being unbalanced.”30

Others agreed. “I saw them hit and field and noted their fine plays here and there, but somehow they lacked refined skills,” wrote a Yakyukai reporter. “Their game strategy was limited. Their poor base running was especially noticeable. Of course, my conclusions could not be definitive after watching just one game, but this is what I observed.”31

The game-two rematch with Mita was a high-scoring affair, with the Royal Giants winning, 10-6. In the top of the seventh inning, the game was tied, 6-6. After shutting down the Mita bats in the inning, the Royal Giants rallied, starting with Cade’s single past third base. Julius Green bunted for an infield hit. With runners on first and second, John Riddle stepped to the plate and hit a line drive off pitcher Shinji Hamazaki’s glove. The ball ricocheted to right field, allowing Cade and Green to cross home plate. With the score now 8-6, Fagen singled past short, driving in Riddle. Dixon doubled to score Fagen for the 10th and final run.32

Overall, the second game was an impressive display of offensive skill, with three hitters having perfect 3-for-3 days at the plate. They were:

- Hamazaki—a single, two doubles, and a walk

- Dixon—two singles, a double, a sacrifice fly, and a walk

- Mackey—two singles, a triple, and two walks

In fact, Mackey’s triple bounced off the center-field fence, which at the time established the record for the farthest ball ever hit at Meiji Jingu Stadium. He later topped that in other games.33

Several baseball magazines and newspapers wrote about the Royals Giants’ skills displayed in their first two games against Mita. The Undo Kai magazine shared their impressions: “On the first day, I was shocked to see how strong their arms were. Every player had one. Especially shortstop Mackey’s ‚Äòbullet ball.’ He had a cannon for an arm, as did Duncan, the first baseman. The catcher Pullen’s powerful arm was beyond our imagination! If I may be allowed to use hyperboles, I’d say that they throw a ball so hard that you cannot even see it. They could throw a ball from second to home, first to third, home to second—straight to its target on a line without a crow hop. Furthermore, they threw with amazing velocity.”34

The editorial added, “With their strong arms, they were good defenders. Rather than being skillful and agile like dogs and rabbits, they were big and powerful like cows and horses.”35

The Undo Kai magazine writers assessed their pitching staff as well. “Cooper threw on the first day, which seemed to indicate that he was the ace of the team. His performance confirmed that he did indeed have the skill of an ace. The rest of the pitching staff didn’t compare to Cooper. Due to the fact that everything else was solid except for their pitching, the Giants were Chujun regarded as a mysterious team.”36

Chujun Tobita, the former manager of Waseda University and an influential figure within Japanese college baseball, had prior experience observing Negro Leagues teams in the United States, and shared his views of the visitors in the Asahi Sports. Based on the two games that he attended in Tokyo, Tobita thought that not every one of the Royal Giants was an elite player.

“When I visited America last year (1926), I truly enjoyed watching the Negro League games in Indianapolis. … [T]he games were just like the major leagues. The only difference was the color of the ballplayers’ skin.” From the stands, Tobita observed that “only half of the players of the Royal Giants team have dark skin, while the rest appear to be mixed race. Those players of many races, whose gloves and hands are the same color, must be considered ‚ÄòAll- Americans.’ The team is not only mixed race, they are mixed talent as well. Many of the players have the appropriate skills to be considered semipros, but not all of them can be considered elite, professional ballplayers.”37

Tobita also possessed an understanding of the history of US race relations and shared a rare perspective from a Japanese national. “Because blacks were once slaves, the whites were perceived as superior in America. And eventually people with yellow skin were discriminated against as well. I suspect that the increasing population of the black race must be viewed as a threat to the white community. It would be especially disruptive to the white baseball community.

“It is odd that American Indians are allowed to join the major league teams, but players of African descent, who are citizens of the country, are not allowed to join. Just because of the color of their skin, they are not treated as equal human beings. They face so much discrimination back home in America—I heard the players say that if a war took place between the US and Japan, they would cheer for Japan. Life is not as simple as baseball. When they say that they would cheer for Japan, they are saying that we are a colored race, too,” Tobita concluded.38

After the two games in Tokyo, the team boarded a train for an overnight trip to Osaka, where they were scheduled to play at Koshien Stadium against Daimai, a semipro team.

In the first game against Daimai, Junior Green pitched the Royal Giants to a 7-2 victory. After a much-needed day off for rest, the Royal Giants returned to Koshien for a rematch. Goodwin selected the multitalented Mackey to start on the mound for the Royal Giants.

The pitcher for the Japanese team was the highly respected star Michimaro Ono. He had pitched for Mita against the Royal Giants in the first game in Tokyo and held the team to just two runs. Ono was known as a fastball pitcher and in 1922 had become a fan favorite when he defeated Herb Hunter’s All- Americans, 9-3—the first victory for a Japanese team over a major-league squad.

Then 30 years old and a bit past his prime, Ono still had something to prove against the Royal Giants. The contest became a pitchers’ duel between Mackey and Ono. By the eighth inning, no Daimai batter had reached second base. The Royal Giants recorded six scattered hits and failed to produce a run … kind of.

In the top of the fourth inning a controversial play occurred. Daimai backup catcher Shigeyoshi Koshiba watched the action from the bench, and years later shared his version of the events.

“There was one out with a runner on third when the [Royal Giants] batter smashed a big hit to right field. The outfielder ran far and made a great play. The runner on third, of course, tagged up to ensure a run. The ball was thrown to the catcher from the right fielder, but it was too late. After that, the catcher threw the ball to first. The runner on first base was trying to run to second and quickly returned back to first, but he arrived late and was tagged out. It was the third out and ended the inning. That was okay, but the umpires should have counted the runner who tagged up from third. The run was made before the third out. However, the umpire mistakenly called ‚Äòno run,’ thinking it was a double play.”39

According to the official records, with one out in the fourth inning, Dixon singled and then Pullen smashed a hit to right field. With runners now on first and third, Cade hit a fly ball to right field. The speedy Dixon tagged up and scored easily. Pullen, not as fleet afoot, failed to make it back to first base in time and was tagged for the third out.

Daimai player Saburo Yokozawa remembered what happened next. “[The Royal Giants] did not argue with the umpire’s call. … Initially, they showed their dissatisfaction with unhappy faces, but they quickly accepted the decision. ‚ÄòIf that’s your call, we will agree with you.’ They accepted easily,just like that. We were the ones in shock.”40

Yokozawa recalled that “some players from the Japanese team tried to point out the erroneous call to the umpire, Tomigashi-kun, but he did not change his ruling. During this time, the Black players started to run onto the field to take their positions, saying, ‚ÄòThat’s okay!’ I could not believe what they did. I have never seen a team act like them before.”41

Now, with the bad call behind them, the Daimai club was batting in the bottom of the ninth inning. With two outs, Yokozawa smashed a single to left field. Sugai then hit a soft fly ball to right field destined for an outfielder’s glove. At that moment it appeared that the game was headed to extra innings as a 0-0 tie, but to everyone’s surprise, Evans, the pitcher turned outfielder, dropped the ball and Yokozawa came home to score the winning run. Daimai defeated the Giants, 1-0. Or did they?

According to Yokozawa, the score was later corrected to a tie game, 1-1. “Even we, the ones who played against them, did not think that we actually won the game,” he confessed. “To tell the truth, everybody in the media was trying to figure out which Japanese team could upset the Royal Giants. Everybody thought that we would be the ones. It might have affected the umpires’ thinking. Maybe they were hoping for the first win by a Japanese team to occur as soon as possible.”42

The Japanese hosts were impressed with the Royal Giants’ display of sportsmanship. “Typically, teams from the US were arrogant,” wrote Kazuo Sayama. “They were full of pride because they believed America was an advanced baseball country. The attitude of most teams was, ‘Let us teach you!’ [I]nstead of, ‘Let us enjoy baseball together!’”43

It is worth noting that this was not Yokozawa’s first interaction with Black ballplayers. He was a member of the championship Meiji University team in 1923, earning the right to tour Hawaii and the mainland United States in 1924. During their four- month goodwill tour, Meiji competed against semipro and college teams—including the historically Black college Howard University. “We always thought that the baseball in America was for white people, so at first we were really confused by their presence,” said Yokozawa.44

On Wednesday, April 6, the Royal Giants played their final contest of the three-game series against Daimai at Koshien. Coming off the 1-1 tie, the Royal Giants were seeking redemption. They attacked early and scored often. They tallied four runs in the second inning and another in the third, giving them a comfortable 5-0 lead through five innings of play. In the sixth inning, the bats of the Royal Giants doubled their total run production, making it a 10-0 ballgame. Daimai brought in Ono in the seventh inning to stop the damage. The Japanese hosts would not score until the bottom of the ninth, when Nakagawa and Takasu started a late-inning rally to score two runs. Final score, a 10-2 victory for the Royal Giants.45

The game also marked a celebrated milestone in the world of Japanese baseball history. The fifth run scored as the result of a triple hit by Rap Dixon off Daimai pitcher Tairiku Watanabe. The fans witnessed history in the making in the third inning, as Dixon’s triple was the longest hit recorded at Koshien at the time.46

Known as “Koshien Dai Undojo” (great public space) when it opened in August 1924, Koshien Stadium was a vast multipurpose community sports stadium used for baseball, rugby, and football (soccer). When used for baseball, the field specifications were:

- Left- and right-field foul poles -361 feet / 110 meters

- Center field—390 feet /119 meters

- Left- and right-center gaps—420 feet / 128 meters

In his record-setting blast, Dixon hit a line drive off the left-center-field fence (420 feet). The speed of the ball was such that after it hit the wall it bounced back toward the infield, allowing him to safely reach third base.

The spot where Dixon’s blast hit the wall was later painted white by Koshien officials to commemorate his great hit for future generations. Unfortunately, the outfield fence of Koshien was later demolished and the white mark was erased. Over time, the name of Rap Dixon was also forgotten in Japan.

The day after Dixon’s record-setting blast, the Royal Giants played their final game at Koshien, a 6-0 victory over the Kansai Daigaku (University) ballclub.47

April 8 marked a day off for the Royal Giants, perhaps a travel day to their next destination, Kyoto. The respite provided time for reflection for manager Goodwin, who wrote a letter to the editor of the Asahi Sports magazine, expressing his gratitude and positive impressions of their first week in Japan. Goodwin wrote:

Dear Japanese players and fans from the baseball field, although we had admired the Yamato race for some years, our respect for you grew immensely after being treated so well by the Japanese people.

In this tour to Japan, our biggest surprise was the quality of Japanese baseball, which is improving and becoming closer to that of a real league. Before we came here, we used to talk about Japanese baseball. We concluded that the Japanese had not reached the professional level yet. However, to our surprise, once we came here and watched the Japanese baseball teams, not only were we amazed, we realized that our prediction was way off from reality.

Even on our way to Japan, we continued to discuss the same topic, and dreamed of Japan as the ship came closer to land. We were most interested to find out what kind of baseball fields there were in Japan. We decided that the Japanese fields must be very tiny, poorly equipped, perhaps the same as Class D fields in America, or promenade-like places. However, after observing the Meiji Shrine [Jingu] Stadium with great earnestness and then seeing the gigantic Koshien Stadium, we realized we were wrong again. Especially Koshien Stadium—it was larger and more splendid than the stadiums in America. The capacity of 80,000 spectators in Koshien Stadium was beyond that of Yankee Stadium, which is proudly said to be the number one stadium in the world after having millions of dollars spent on it. In comparison to Koshien Stadium, Yankee Stadium would be dwarfed.

The difference between the two stadiums is that Yankee Stadium is privately owned by a rich club, while Koshien is used by everyone. This should be emphasized, so that Koshien Stadium stands proudly.

Throughout the games against the Japanese teams, we could not help but be amazed by the aggressive nature of their defense. We reckoned that they knew how to play inside baseball. Up to today, we lost one important game to the Daimai team, but this was a scoreless game to the end and a fantastic fight between our captain Mackey and the ace pitcher, Ono, of the Diamonds. Unfortunately, it became our first loss since we arrived in Japan. However, we truly enjoyed the game that was played by the Yamato souls. We not only admired and praised the skillful pitcher Ono, but we also thought that the Daimai Club were not any lesser than a major league team in the way they fought back with Ono as a leader in that day’s game.

We believe that Japanese baseball will continue to thrive greatly in the future. However, our admiration for Japanese baseball is due not only to the skills that were shown in the Daimai game, but also to the respectable sportsmanship that the Japanese players demonstrated.

Frankly, we think there is not any other country where we could play and enjoy games while not paying any attention to wins or losses. We especially admire the passionate baseball fans, who are well educated and watched the games with respectful manners. That left us with a great impression of Japanese baseball. The more we thought about the dilapidated American stadiums, the better and nobler the Japanese stadiums appeared. We think that the stadiums are used by all the fans, and are for the Japanese people to enjoy real sports.

We wish great success and a promising future to Japanese baseball society, and we also express thankfulness for their hospitality and kindness from the bottom of our hearts to our Japanese hosts through Asahi Sports.

Lon Goodwin

Manager, Philadelphia Royal Giants April 8, 192748

The Royal Giants mesmerized others wherever they went in Japan, both on and off the field. Reporter Takeshi Mizuno discussed his thoughts on the personality and style of the Royal Giants in the June 1927 issue of Yakyukai. Under the headline “The Gentle Baseball Players,” he wrote:

Even during the game, they were relaxed. Their actions and behavior in the hotel after the game were mellow as well. The volume of the conversation among themselves was kept to a minimum. Nobody could tell if they were there or not. During the interviews after the game, they responded with humility. The gossip by the women in the rear tenement was noisier.

Mr. Irie shared these qualities. Their personalities were very calm and they were cordial. Because they lived in a white-dominated country and were not treated equally in America, the blacks related more to the Japanese American side in America, and liked the Japanese Americans. In this tour to Japan, they all enjoyed themselves, and they received a big welcome everywhere they went. They were uncomfortable at times because they were not used to this sort of positive treatment, but they had big smiles on their faces.

When they were not playing baseball they liked to shoot billiards and go for walks for enjoyment. They also adored children and played with them gleefully. When they played billiards in the hotels, which they did often, they respectfully took turns to shoot. They also went to cafes and such, without any special agenda.49

After getting much-needed rest and relaxation, the team zig-zagged across central Japan by train, competing against college and industrial ballclubs, and one of the earliest professional teams, the Takarazuka Club. Officially known as the Takarazuka Athletic Association, they were founded as the Shibaura Association after Kazumi Kobayashi bought the team and combined it with Hankyu Railway.

Considered by many to be the best team in Japan, the Takarazuka Club outslugged the Royal Giants 11-10 in base hits. Shut out until the ninth inning, Takarazuka fought hard and managed to score three runs to threaten the Royal Giants, but still ended up on the losing end of a close 4-3 ballgame.50

Goodwin and his club had a three-day break for rest and travel for their next series of games back in Tokyo, where they battled the popular Tomon Club and Sundai Club.

They headed to the bustling section of Tokyo known as Kanda-nishikicho and stayed at the Hosenkaku Hotel, a majestic, Western-style hotel located near the Shinbashi station. Despite the convenience of train travel, the team preferred automobiles and drove through the Yotsuya and Akasaka sections of the city to enjoy the cherry blossoms in full bloom.51

Other sites in Japan that impressed the Royal Giants’ players included the Miyako Odori (a traditional spring dance festival) in Kyoto, the Azuma Odori (indoor stage show) in Tokyo, the hot spring baths in Beppu, and the performances by the geishas who “moved swiftly, all legs and elegant, swaying hands.” The players praised the dancers, “Oh, beautiful! Beautiful!” The Royal Giants told their hosts that what they really wanted was to bring their friends and family to experience Japan instead of just telling them about it.52

The Royal Giants’ game on April 16 against Tomon was played at Waseda University’s Totsuka Field. Meiji Jingu Stadium was not available because the other US team touring Japan, the Japanese American Fresno Athletic Club, had booked a game there the same day against Hosei University. Both American teams were popular in Japan, so fans in Tokyo struggled to decide which game to attend.

Additionally, the Tomon Club, which consisted of Waseda players and alumni, had lost many star players, as the Waseda varsity team had left for America on a goodwill tour of their own. The Royal Giants defeated Tomon, 6-2, behind the pitching of Ajay Johnson. Photographs featured in Asahi Sports showed fans packed in the stands, filling all the seats from the infield to the outfield.53

The next day fans returned to see the same two teams do battle. Tomon fastball pitcher Shoichiro Tase carried the weight of the crowd on his shoulders. He lacked a good breaking ball, so the Royal Giants sat on his fastball all day and feasted on his pitches.

Dixon hit a home run over the left-field wall, as well as a triple. Mackey also hit a double to left-center. These two alone accounted for the bulk of the runs, while Evans and Cooper held the Tomon batters to just one run on nine scattered hits. The Royal Giants defeated Tomon, 8-1.54

A former Tomon player, right fielder Kimitsugu Kawai, reflected years later how the games against the Royal Giants were for many Japanese their first exposure to people of African descent. “We were all surprised that everybody was so dark. I remember that we joked around. … We thought that if we played with them, the white ball would turn black,” he confessed.55

Kawai also recalled that even though the Royal Giants were very good players and popular in Japan, at the time of their game he had heard reports that the team was struggling to earn enough money for their return tickets home. “We felt disappointment for them when we heard about their situation.”56

The Japanese fans had high expectations for the matchup between the Royal Giants and the Fresno Athletic Club, scheduled for April 20. It was the FAC’s second tour of Japan, so they had many Japanese fans. The team was made up of talented Nikkei (Japanese American) players and three White players—Charles Hendsch, a relief pitcher; Eldridge Hunt, starting pitcher; and Jud Simons, a catcher. The FAC had yet to lose a game during their second tour.

Additionally, FAC coach Kenichi Zenimura repeatedly told the Japanese press that he was eager for a rematch against the visiting Black team, which his team had defeated several times in California.

After reading Zenimura’s statements in the newspapers, newcomers to Goodwin’s team did not take kindly to his comments. For many of the star players, this was their first time competing against the FAC, but for others who were members of the L.A. White Sox, they knew the truth. Perhaps Goodwin used Zenimura’s case of mistaken team identity as fuel for his players? We may never know for sure. What we do know is that star additions like Mackey, Dixon, Duncan, and Cooper played angry, and it was to their advantage in the end.57

A sellout crowd filled Meiji Jingu Stadium to witness the battle between the two American teams. The Royal Giants relied on their ace, Andy Cooper, while Fresno sent Thomas Mamiya to the mound. The Royal Giants bats were hot early. With two outs in the first inning, Mackey smashed a triple to left-center field. Dixon hit a line drive to right field, scoring Mackey. Mamiya made the necessary adjustments and cooled off the Royal Giants’ bats.

The Fresno ace lost steam in the sixth inning. Mackey belted a solo home run to deep center field. The next inning, the Royal Giants scored four more runs on a combination of singles and extra-base hits—consecutive singles by Walker, Cooper, and Fagen, followed by a sacrifice fly by Mackey and a triple by Dixon. The power continued in the eighth inning. With the bases loaded—Cade had doubled, Green walked, and Walker singled—Fagen drove in a run, and Mackey smashed a double, scoring three additional runs.

Trailing 9-0 in the bottom of the ninth inning, Fresno pinch-hitter Simon doubled off Cooper, and pinch-hitter Sam Yamasaki drove a single to right field, scoring Simon for Fresno’s lone run. Goodwin’s team defeated Zenimura’s, 9-1.58

Additional observations about the game were detailed in the June 1927 issue of Undou Kai (Athletic Society) magazine.

These undefeated teams prepared their best lineups as if they were trying to win a championship. The Fresno team used their starting pitcher, Mamiya, and the blacks sent out a big left-handed pitcher, Cooper, but there was no competition between the two. Mamiya had a sturdy, big body for a Japanese person and threw hard, but Cooper was like a hornless bull and threw fastballs from his shining, black, muscular arm. The velocity of their pitches was incomparable. No one from the Fresno team could hit Cooper’s heavy, fast sinker. The power and speed startled Fresno. At times they could not even swing their bats. On the other side, the pitches from Mamiya added fuel to the blacks’ fiery offense. They hit his slow ball and curve ball without mercy. He gave up one home run, three triples, two doubles, and a total of 17 hits. This performance was evidence that his skill was not as great as Cooper’s.59

Offensively, every Royal Giants batter recorded a hit except Green. Hitting cleanup, Dixon had two triples and a single. Mackey was the MVP of the day, a single shy of hitting for the cycle, driving in seven of the Royal Giants’ nine runs.

According to Sayama, the difference in power between the two teams was shown in this battle. Mackey’s home run especially symbolized it. In fact, this home run was the first one ever hit over the fence in Meiji Jingu Stadium.”60 The ball passed over the head of the center fielder, went over the fence, and bounced on the grass of the bleacher section before disappearing outside the stadium.

The home run against Fresno was the first of three round-trippers for Mackey at Meiji Jingu. He hit one to all sections of the outfield:

- His first: April 20 off Fresno pitcher Thomas Mamiya, sixth inning, first batter, first pitch, over the center-field bleachers (417 feet/ 127 meters).

- His second: April 25 off Sundai Club pitcher Tadashi Nakatsugawa, seventh inning, one runner on base, one ball and two strikes, hit to the left-field bleachers (358 feet / 109 meters).

- His third: April 28 off Saint Paul Club pitcher Shuzo Nawaoka, third inning, first batter, first pitch, hit to the right-field bleachers (358 feet / 109 meters).61

After a scheduled rematch against Fresno was rained out the next day, the Royal Giants players enjoyed a four-day break before their next contest, against the Sundai Club. On April 25 at Meiji Jingu Stadium, Ajay Johnson pitched a two-hit shutout, leading the team to an 8-0 victory. The offensive highlight of the day was a sixth-inning home run by Mackey into the left-field grass section.62

Royal Giants pitcher Johnson continued his dominance against Japanese batters with a 14-0 shutout against Rikkyo University (aka Saint Paul’s University) on April 28. He allowed six hits and one walk. According to Yakyukai, “The game was a devastating loss. … It was an unavoidable loss and it was expected.” Rikkyo committed 10 errors, so not even the Royal Giants, who made it a practice to keep the games competitive to attract fans for future games, could have kept the score close.63

Some disappointed fans lingered in the stadium after the game. In their attempt to please the audience, the Royal Giants held an impromptu baseball skills demonstration—something the crowd had never seen before:

- Dixon showed off his arm by throwing one ball after another from home plate over the outfield wall and beyond the left-field grass section. Both fans and opposing players were amazed.

- Next, Mackey entertained the crowd by hitting balls to the outfield grass sections. He tossed the ball up to himself and displayed his beautiful hitting form.

- The skills demonstration concluded with Duncan and Dixon showing off their baserunning. They ran around the diamond in 14.02 seconds, amazing the Japanese fans.

Until then, teams that came to Japan usually entertained fans by acting goofy, making silly faces, or performing imitations of birds and running around mimicking bird calls. Sometimes they performed silly dances during the games. Some Japanese players and fans were annoyed by these childish acts.64

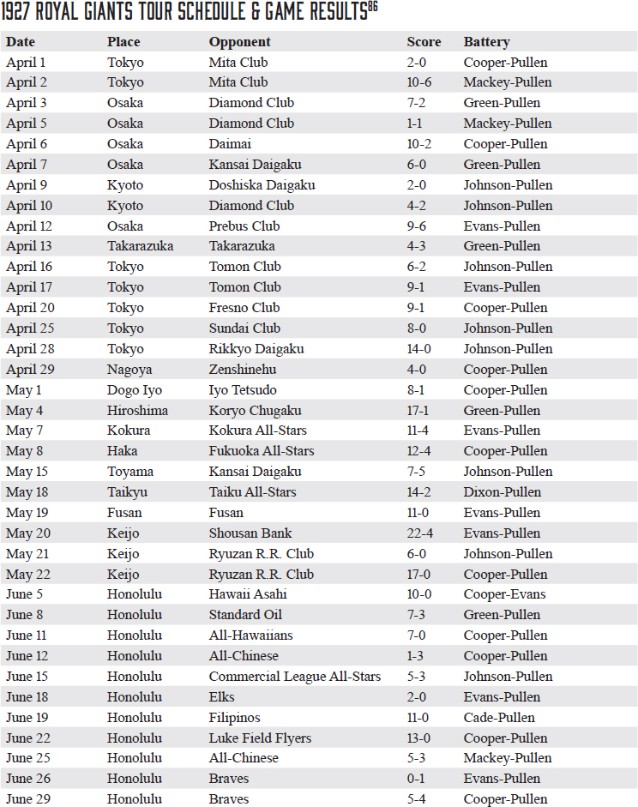

With 13 games completed (and a 12-0-1 record), the Royal Giants left Tokyo again for a tour that included stops in Nagoya, Hiroshima, Fukuoka, and Toyama. Details and highlights from the final six games in Japan were not published, but we know that the team went undefeated, with Cooper and Pullen doing the majority of the battery work.65

Except for a 17-0 defeat of Koryo Junior High School, the Royal Giants kept the scores close and the games competitive against the Japanese teams. The indelible impressions they made stuck in the memory of Yasuo Shimazu, Diamond Club shortstop, who reflected on playing against the all-Black team from the United States:

I wonder if the Royal Giants were purposefully making the game fun for the fans. Because of that, we were able to play great games. … It was later when I started to think this way. While we were playing, we did not even think about it. We were just playing hard. At that time, one of my cousins was living in America. I heard about the caliber of the Negro Leagues from him. I might have had preconceptions about them. He told me so many times about the level of black baseball and how it was not any lower than that of the major leagues. We held our own against a team that was as good as a major league team. . We were totally ecstatic. However, when I reflect on it now, this was not the case. The major league team came to Japan soon after and compared to them we were like a little league team. The major leaguers must have felt that we were no competition, so they were goofing around on the field. I am not sure where the game occurred, but this is what I saw.

While Lefty Grove was pitching, the left fielder, A1 Simmons, lay down at his position. The shortstop, Maranville, turned his back to the batter. He sometimes put his face under his crotch and yelled, “Hey, Come on!” In 1934, Babe Ruth played defense while holding an open umbrella during a rainy game. He also played with his rubber boots on. Although they were trying to be playful for the fans, it was not fun for us. We were disappointed in ourselves for the difference in our abilities, and at the same time, we could not hold our composure to endure their foolishness. The black team, however, was not like that. They were trying to play a competitive game. They also provided fans entertainment, but they never made fun of anybody. What they did was show off their arms by making long throws, and show off their speed on the bases. As for the catcher, he threw the ball like an arrow down to second base on his knees, but during the games, he stood up and threw it down like a textbook play.

As for the black baseball team, they made their money from the spectators. They needed to do something fun in order to get as many people as possible to come watch the games. We did not think of that. We thought that we had close, competitive games because of our ability. … It was shown in their attitude, I think. They worked so hard to try to win. We were so amazed that we were competing head-to-head. They seriously made us think that we were as good as them. While they acted like they were playing hard, they were actually pretending in order to push us to play our best, which resulted in an entertaining game for the fans. … I wonder if this was what they were trying to achieve.66

On May 16-17, the Royal Giants played a two-game series against Kansai University in Toyama. Game one resulted in a 7-5 victory powered by the battery of Cooper and Pullen, and game two a 10-4 victory behind Johnson and Pullen. The team then boarded a ship for Korea, where they would play five more games.67

The team left Kobe on May 17 for the Japanese- occupied colony of Chosen, the Japanese name given to the country known today as Korea. The games were organized by the Keijo Nippo, the Japanese- language newspaper authorized by the government. Additionally, the newspaper promoted the tour as contests against Korea’s “strongest teams” but all the opposing players and teams turned out to be Japanese—the last two being Yongsan Railway Club and the Industrial Bank. Thus, Korean athletes were excluded entirely from playing in these games, making the final five games, in essence, just an extension of the Japan tour.

On May 18, the Royal Giants defeated the Daegu All Stars, 14-2, behind a rare pitching appearance by outfielder Rap Dixon. The next day the team traveled south to Busan, where it delighted the fans with an impressive win over a local ballclub. Slowtime Evans pitched a shutout, winning 11-0.

The Royal Giants next traveled to Seoul for three games, where they received special diplomatic treatment. Two welcome banquets were held on May 20 and 21, and their parade was filmed for a newsreel. At the May 20 game, US Consul General Ransford Stevens Miller honored the Negro Leaguers with a ceremonial first pitch, perhaps marking one of the earliest times for a White American official to participate in a Negro League baseball pregame ceremony.

According to historian Kyoko Yoshida, the Royal Giants’ final three games in Korea were the most political of the entire tour. Japanese government officials saw the games as a way to demonstrate Japanese political and cultural supremacy through baseball. “The American game helped shape not only the Japanese identity but also its empire,” said Yoshida. For the Negro Leaguers, it was a chance to show off their power and pride in the presence of White American politicians. Thus, the Royal Giants won by wide margins in these games, including a 22-4 victory in the game witnessed by Miller.

In late May, the Royal Giants boarded the Siberia Maru of the Nippon Yusen Kaisha Line and sailed for Hawaii for a final 11-game series. After the 4,540-mile journey, they reached Honolulu on June 4. The next day the Royal Giants arrived at Honolulu Stadium for a game against the Asahi, the local Japanese American team. Over 8,000 fans gathered for the game, many of whom were familiar with the exceptional talent of Negro Leagues baseball. A decade earlier, many watched the likes of Bullet Rogan, Dobie Moore, and Heavy Johnson compete with the mighty 25th Infantry Wreckers while stationed at the Schofield Barracks. In fact, the Honolulu newspapers often incorrectly referred to the visiting team in 1927 as “Rogan’s Giants.”68

In the first game in Hawaii, Asahi pitcher Jimmie Moriyama struck out several of the Giants batters, but star players Cooper and Mackey led the Royal Giants to an easy 10-0 victory over the local club.

Evans shifted behind the plate to give a rest to Pullen, who enjoyed a rare afternoon in left field. In the eighth inning, Pullen made the highlight play of the day with a long, spectacular run for a fly ball. He had to leave his feet to catch the ball and in doing so executed a perfect dive—catching the ball as he hit the ground. Because of his size and speed, he slid along the green grass on his stomach for at least 10 feet, holding the ball high in his glove for all to see that he had indeed made the catch.

The press described the Royal Giants as “one of the most popular teams ever seen in action here,” adding, “They are full of pep, fun, and good baseball.”69

After a 7-3 victory over the Standard Oil club that boasted former major-league pitcher Johnnie Williams, the Royal Giants experienced their first undisputable defeat of the tour, a 3-1 loss to the AllChinese ballclub. Dixon belted a triple in the first inning and scored on Pullen’s sacrifice fly, but after that the Giants’ bats went cold. Yu Chun, a side-arm pitcher for All-Chinese team, stifled the Royal Giants, striking out nine batters. Cooper had eight strikeouts, and allowed just one run in the first inning and two runs in the fourth.70

After the game, many fans thought that the Royal Giants threw the game. Honolulu Stadium manager J. Ashman Beaven came to their defense. “Personally I think the story about the game being thrown is nothing but a lie,” he said. “The Chinese defeated the Giants fair and square and I am positive that the visiting players would not even consider being unsportsmanlike or unfair in any way.” Beavan offered $500 to anyone who could provide proof that the Giants threw the game. “I merely make the above offer to show to the public that these stories are nothing but lies,” he said.71

On June 26 the Royal Giants lost its second game of the tour to the Honolulu Braves and their curveball artist Sam Guerrero. The Giants outslugged the Braves, eight hits to four. They were able to put runners in scoring position but failed to drive in runs. The Braves shortstop, Camacho, went l-for-3 at the plate and scored the game’s only run. In light of the fixed-game controversy, one Hawaii newspaper ran the headline: “1-0 The Royal Giants proudly lost the game!”72

After the game, the Royal Giants gathered for a joint team photo with the Asahi, who were waiting to play the second game of the twin bill. In the photo, manager Goodwin and star player Mackey gripped a large trophy and pennant presented to the team by the Hawaii Undokai, a Japanese sports organization.73 Among the Asahi players was a young relief pitcher named Tadashi “Bozo” Wakabayashi, an 18-year-old who would later attend Hosei University and become the ace of the Osaka/Hanshin Tigers, and an eventual member of the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame.

After 11 games in Hawaii, the Royal Giants sailed home on July 2, and arrived home six days later, on July 8. In total, the Philadelphia Royal Giants Goodwill Tour of 1927 lasted 121 days (March 9 to July 8) and covered 13,305 miles.74 The well-traveled and weary team played a total of 38 games, finishing with a 35-2-1 record. They won 21 of 22 with a tie in Japan, were 5-0 in Korea, and had a 9-2 record in Hawaii.

One might think that the Royal Giants were welcomed home with a heroes’ parade. They were not. The star players of the team returned to the United States to discover that they all faced a possible five-year ban from their Negro League clubs in the East. Mackey, Cooper, Dixon, and Duncan all faced career-ending punishment for “jumping their contracts” and missing regular-season games while across the Pacific. The players appealed, and asked for forgiveness and for their suspension to be reduced. Their pleas worked. They all received a lesser penalty of a $200 fine and a 30-day suspension.75

Despite the new terms of the agreement with the league, all but one of the managers put their star players back on the field almost immediately. The Chicago Defender observed, “Hilldale played Mackey as soon as he could get into a uniform on his return. Harrisburg did the same with Dixon and Detroit did the same with Cooper. Only one owner lived up to the agreement. He was J.L. Wilkerson of the Kansas City Monarchs [regarding Frank Duncan].”76

Goodwin’s club received an offer to return to Hawaii the following year at the request of Kanichi Takizawa, an official with the Oahu Plantation Japanese Baseball League, and president and publisher of Sports of Hawaii, a Japanese monthly magazine devoted to athletics.77

Shortstop John Riddle also received an offer to return to Hawaii, but not for baseball. A professional football team in Hawaii invited him to return, and even added an incentive to put his degree from the University of Southern California to work with a position in an architect’s office.78

While manager Goodwin and other players crossed the Pacific again for games in Hawaii and Asia during the late 1920s and early 1930s, not everyone did. Pitcher Ajay Johnson returned to the Los Angeles Police Department but kept a prized ukulele in his home and strummed it with joy as he fondly reflected on his baseball experiences abroad.79

Between 1928 and 1931, the Royal Giants made several tours to Hawaii, where they continued to barnstorm across the Pacific and lay the foundation for future tours to Japan. Catcher O’Neal Pullen organized two tours to Hawaii, as the Cleveland Royal Giants in 1928 and as the Pullen Royal Giants in 1929. His teams played 44 games, finishing with a 29-14-1 record.

After a brief hiatus, the team returned to Hawaii in 1931 as the Philadelphia Royal Giants under the leadership of manager Goodwin. Goodwin’s roster featured several Cuban players, including Clemente Delgado, Virginio Gamiz, Javier Perez, and Eusebio “Miguel” Gonzales. The presence of the light-skinned Gonzales is noteworthy—he played for the 1918 Boston Red Sox, thus his inclusion perhaps marks the first time for a former major leaguer to participate in a Negro League tour.80

These summer tours to the islands gave the new members of the Royal Giants an opportunity to build chemistry on the field, and off-field business relationships. During the 1931 summer Hawaii tour, Goodwin arranged for Honolulu Asahi team owner Steere Noda to join the Royal Giants for another tour to Japan in 1932. The 1932-33 tour of Asia was a success. Between July 23, 1932, and January 14, 1933, the team played 46 games in 175 days, covering a distance of 15,819 miles.81

Just as he had during the 1927 tour, Mackey continued to mesmerize fans and make headlines during the 1932 tour. Biz dazzled fans in Hawaii by playing all nine positions against the Honolulu Asahi. He started the game at catcher, worked his way across the infield during the next four innings, all three outfield spots in the sixth, seventh, and eight innings, and closed the game on the mound. The Royal Giants easily trimmed the Asahi, 5-1. After going undefeated in Hawaii, the team played 24 games in Japan, finishing with a 23-1 record. The most notable moment of this tour occurred in the second game in Japan, a 10-7 victory over Tomon. In the eighth inning, relief pitcher Wakahara hit Mackey with a wild pitch. Wakahara took off his cap and bowed respectfully to apologize. Mackey respectfully bowed back before taking his base.82

The Royal Giants returned to Japan again in December 1933, but the winter rain did not allow for any games to be played, so the team continued on to the Philippines and Hawaii. Fans in Japan missed out seeing baseball greats in action like Bullet Rogan, Chet Brewer, Dink Mothell, and Andy Cooper.83 Still, the earlier tours of the Negro Leaguers left their mark on the people of Japan.

Historian Kaz Sayama believes, “Had the great all-stars from the major leagues suddenly arrived in Japan in 1927, our elite players might have lost their desire for baseball. It might have made them think it would be a mistake to form a professional team in Japan. They could have been discouraged from building for the future of Japanese baseball. … [T]he Black American ball club returned to Japan at the best possible time.”84

According to Sayama, the 1931 tour of the major league All-Americans left the Japanese feeling disheartened by the results of the games. But instead of feeling helpless, they had been “immunized” with hope by the Royal Giants four years earlier. Goodwin, Mackey, Cooper, Dixon, Duncan, and the others helped the Japanese players prepare for and accept their losses with a positive attitude. “The gentleman-like black giants … live in the hearts of the Japanese players,” says Sayama.85

The year 2022 marked the 150th anniversary of US-Japan baseball relations (1872-2022). For decades no one talked about the Royal Giants and the important role they played in the emergence of professional baseball in Japan. That changed because of the passionate efforts of historian Kazuo Sayama, who captured the stories of the Japanese players who faced them and preserved them for future generations to appreciate. The legacy of the first Negro League team to tour Japan—the 1927 Philadelphia Royal Giants—will live on forever as well.

BILL STAPLES JR. of Chandler, Arizona, a SABR member since 2006, has a passion for researching and telling the untold stories of the “international pastime.” His areas of expertise include Japanese-American and Negro Leagues baseball history as a context for exploring the themes of civil rights, cross-cultural relations, and globalization. He is a board member of the Nisei Baseball Research Project and the Japanese American Citizens League-Arizona Chapter, chairman of the SABR Asian Baseball Committee, and research contributor to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. Staples is the author of Kenichi Zenimura, Japanese American Baseball Pioneer (McFarland, 2011), and co-authored Gentle Black Giants: A History of Negro Leaguers in Japan (NBRP Press, 2019) with Japanese baseball historian Kazuo Sayama. He has contributed to numerous articles and news stories for global media including MLB.com, Sports Illustrated, NPR, the Japan Times, Kyodo News, TV Asahi, and NHK. His other SABR publications include articles in Baltimore Baseball (2021), One-Hit Wonders (2021), and No-Hitters (2017). He received the SABR Baseball Research Award in 2012 for the Zenimura biography and in 2020 for the article “Early Baseball Encounters in the West: The Yeddo Royal Japanese Troupe Play Ball in America, 1872.” Learn more at zenimura.com.

NOTES

1 Kazuo Sayama and Bill Staples Jr., Gentle Black Giants: A History of Negro Leaguers in Japan (Fresno, California: Nisei Baseball Research Project Press, 2019), 19.

2 Sayama and Staples, 10.

3 Sayama and Staples, dedication/front matter.

4 Sayama and Staples, 19.

5 “Tigers Gave Japs Jiu Jitsu,” Lexington (Missouri) Intelligencer, May 23, 1908: 8.

6 “Travelers, All-Army and P.A.C. Teams Win,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, December 6, 1915: 13. Robert Fagen’s name is often misspelled as Fagan.

7 The Japanese community on the island of Hawaii embraced the 25th Infantry Wreckers. Their passion for the team and its players is encapsulated in the efforts of a young Nisei ballplayer, Itaru Miyanishi, who fell in love with the game of baseball watching the all-Black Wreckers in Honolulu and later had his first name legally changed to Rogan.

8 “Defeats Japanese Nine,” Washington Evening Star, June 3, 1924: 30.

9 “Fresno, 5; White Sox, 4,” Los Angeles Times, September 7, 1925: 13.

10 “All-Star Baseball Club May Go to Japan,” Chicago Defender, February 5, 1921: 6.

11 “All-Star Baseball Club May Go to Japan.”

12 “Fresno All-Stars Win Again from L.A. Team, 4 to 3,” Fresno Bee, July 6, 1926: 10.

13 Bill Staples Jr., Kenichi Zenimura, Japanese American Baseball Pioneer (Jefferson North Carolina: McFarland, 2011).

14 “F.A.C. Team Wins in Japan,” Fresno Morning Republican, December 5, 1924: 19.

15 “Negro Baseball Team to Japan,” Nippu Jiji, December. 21, 1926: 10.

16 Motomitsu Matsumoto, Japanese Who’s Who in California (Tokyo: Bunsei Shin, 2003).

17 Kyoko Yoshida, “Appendix G: Biography of George Irie,” in Sayama and Staples, Gentle Black Giants, 203.

18 Yoshida, “Appendix G: Biography of George Irie,” 203.

19 Sayama and Staples, 161.

20 “Goodwin Flays Big League Salaries on His Departure,” Afro-American, March 19, 1927: 14.

21 Sayama and Staples, 65.

22 Kyoko Yoshida, “Barnstorming the Empire: The 1927 Philadelphia Royal Giants Visit Colonial Korea,” in Sayama and Staples, 270.

23 “Mita vs. Black People Game One,” Yakyukai, May 1927: 110.

24 “Mita vs. Black People Game One,” 110-112; Sayama and Staples, 32.

25 Yoshida, “Barnstorming the Empire: The 1927 Philadelphia Royal Giants Visit Colonial Korea,” 270.

26 “Mita vs. Black People Game One,” 110-112; Sayama and Staples, 33.

27 “Mita vs. Black People Game One,” 110-112; Sayama and Staples, 34.

28 “Mita vs. Black People Game One,” 110-112; Sayama and Staples, 34.

29 “Mita vs. Black People Game One,” 110-112; Sayama and Staples, 34.

30 Sayama and Staples, 35.

31 Uncredited article in Yakyukai, May 1927: 108-09, quoted in Sayama and Staples, 35.

32 “Mita vs. Black Team Game Two,” Yakyukai, May 1927: 112-114; Sayama and Staples, 36.

33 Sayama and Staples, 36.

34 Aomine [first name unknown], title unknown, Undo Kai, May 1927, quoted in Sayama and Staples, 39.

35 Aomine, 39.

36 Aomine quoted in Sayama and Staples, 40.

37 Suishu Tobita quoted in Sayama and Staples, 44.

38 Tobita, 44.

39 Shigeyoshi Koshiba quoted in Sayama and Staples, 49.

40 Saburo Yokozawa, interview with Kazuo Sayama, 1983, quoted in Sayama and Staples, 50.

41 Yokozawa, 50.

42 Yokozawa, 50.

43 Sayama and Staples, 49.

44 Yokozawa, 42.

45 Sayama and Staples, 54.

46 Sayama and Staples, 55.

47 “Royal Giants Won 26; Tied One on Their Japanese Tour,” Chicago Defender, June 25, 1927: 9.

48 Lon Goodwin to Asahi Sports, April 8, 1927, quoted in Sayama and Staples, 53.

49 Takeshi Mizuno, “The Gentle Baseball Players,” Yakyukai, June 1927, quoted in Sayama and Staples, 51.

50 Sayama and Staples, 61.

51 Uncredited article in Yakyukai, June 1927, quoted in Sayama and Staples, 72.

52 Sayama and Staples, 72.

53 Sayama and Staples, 73-74.

54 Sayama and Staples, 75.

55 Kimitsugu Kawai, interview with Kazuo Sayama, quoted in Sayama and Staples, 76.

56 Kawai.

57 Sayama and Staples, 265.

58 Sayama and Staples, 80.

59 Uncredited article in Undou Kai, June 1927, quoted in Sayama and Staples, 81.

60 Sayama and Staples, 83.

61 Sayama and Staples, 84.

62 Sayama and Staples, 88.

63 Uncredited article in Yakyukai, June 1927, quoted in Sayama and Staples, 89.

64 Yasuo Shimazu interview with Kazuo Sayama, quoted in Sayama and Staples, 64-65, 90.

65 Sayama and Staples, 248.

66 Shimazu.

67 Kyoko Yoshida, “Barnstorming the Empire: The 1927 Philadelphia Royal Giants Visit Colonial Korea,” 272.

68 William Peet, “Braves Blank Rogan’s Giants in Stadium Game 1-o,” Honolulu Advertiser, June 27, 1927: 5.

69 Pete Doster, “Rogan’s Giants Whitewash Asahis in First Appearance,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, June 6, 1927: 11.

70 Pete Doster, “Giants Defeat Standard Oil Outfit in 7-3 Game,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, June 9, 1927: 10.

71 “‚ÄòFaked Game’ Stories Draw Hot Reply from J.A. Beaven,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, June 14, 1927: 8.

72 Sayama and Staples, 102.

73 “Stadium Shorts,” Honolulu Advertiser, June 27, 1927: 6.

74 Sayama and Staples, 241.

75 “30 Day Suspensions for Four Players,” Afro-American, July 9, 1927: 15.

76 “Fays Says—Mackey Jumped,” Chicago Defender, September 24, 1927: 8.

77 “Negro All-Stars Agree to Play Here Next Year,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, December 3, 1927: 8.

78 “‚ÄòPros’ Ask for Jonnie Riddle,” Afro-American, July 23, 1927: 14.

79 Arnold P. Townes (Ajay Johnson’s nephew), phone interview September 2008.

80 Sayama and Staples, 301.

81 Sayama and Staples, 284.

82 Sayama and Staples, 121.

83 Sayama and Staples, 329.

84 Sayama and Staples, 68.

85 Sayama and Staples, 154.

86 “Royal Giants Won 26; Tied One on Their Japanese Tour,” Chicago Defender, June 25, 1927: 9.