George Scales and the Making of Junior Gilliam in Baltimore, 1946

This article was written by Stephen W. Dittmore

This article was published in The National Pastime: A Bird’s-Eye View of Baltimore (2020)

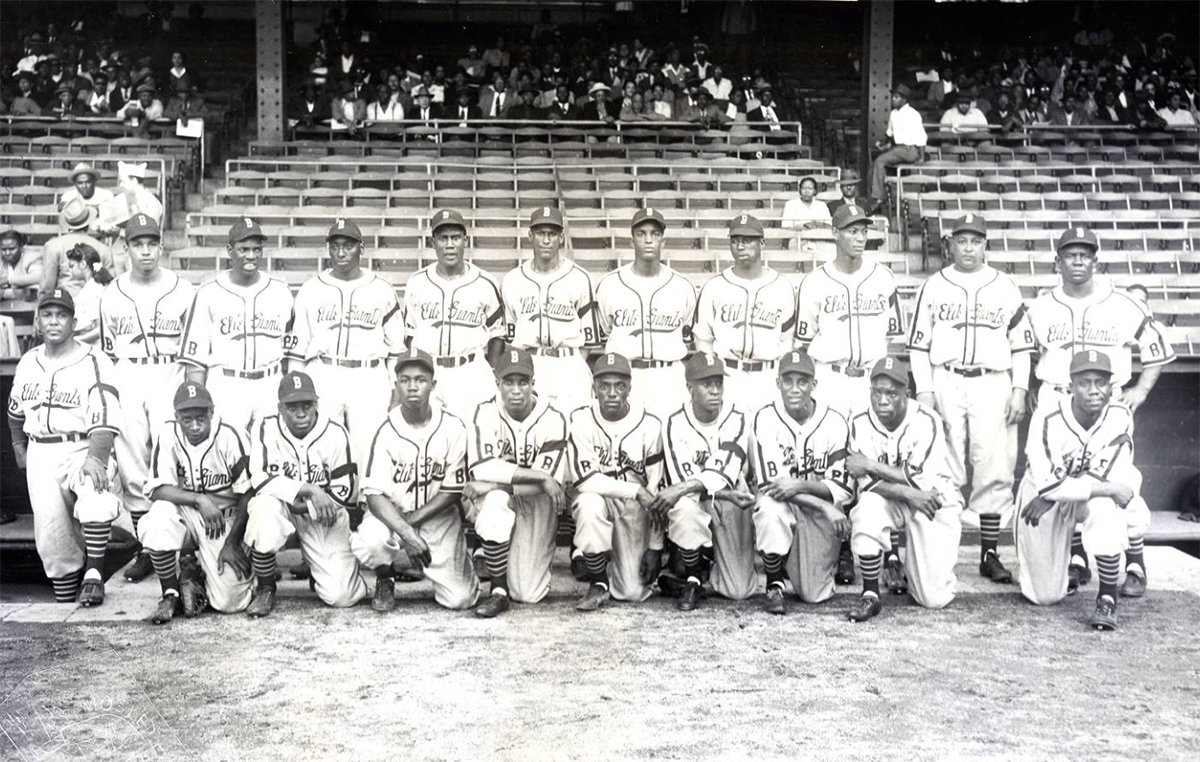

The Baltimore Elite Giants. In the front row, Tubby Scales is on the far left, Junior Gilliam is fourth from the left, and Henry Kimbro is in front on the far right.

Spring training for the Baltimore Elite Giants of the Negro National League began April 1, 1946, at Sulphur Dell in Jim Gilliam’s hometown of Nashville. A brief story in the Nashville Tennessean about the Nashville Cubs, previously the Black Vols, beginning practice alongside the Elite Giants indicated “James Gilliam” would be returning to the Nashville team at third base.1 The Cubs ostensibly served as a minor-league affiliate of the Elites. With established veterans around the Elites infield, the 17-year-old Gilliam likely figured to be nothing more than organizational depth for owner Tom Wilson’s clubs.

During camp, however, Gilliam caught the eye of George Scales, Baltimore’s former manager and current road secretary. George Louis Scales (sometimes listed as George Walter Scales2) was born August 16, 1900, in Talladega, Alabama. In his 33 years in the Negro Leagues, Scales played all four infield positions as well as the outfield and served several years as a manager. He was a steady hitter who in 743 games amassed a .312 average with 59 home runs and 502 runs batted in.3 Bill James ranked Scales as the third-best second baseman in Negro Leagues history in his New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, describing him as a power hitter who “was both fast and quick, but tended to put on weight (he was called ‘Tubby’).”4

Scales broke into the professional black baseball in 1919 as a member of the Montgomery Grey Sox. On April 2, 1938, he found himself at Wilson Park in Nashville, site of spring training for the Elites, assuming the role of player-manager following a stint with the New York Black Yankees.5 In 1946, Scales served as the team’s road secretary, with Felton Snow as manager.

By all accounts, Scales was a knowledgeable manager, well-liked by players. Long-time Elites shortstop Tommy “Pee Wee” Butts, a perennial Negro League all-star, said, “Scales was a little hard on you, but if you’d listen you could learn a lot. . . . Scales could get what he needed out of you.”6

Scales would get plenty out of Gilliam that spring. “Well, it’s true, I’m the one gave Junior Gilliam his chance. I forced them to play him,” Scales said decades later. “Gilliam was a kid had come up from Nashville with the team as a third baseman. The manager had a friend he brought up to play second, but that guy was nothing. So I went to Vernon Green, the owner, and said, ‘Make that man put Gilliam on second,’ and he did, and that was it.”7

The “nothing” player was presumably Frank Russell, who was mentioned as the projected starter in the Baltimore Evening Sun.8 Russell, also a former Black Vol, played second base for the Elite Giants in 1943 and 1944, but shifted to third base in 1946. He would bat only .182 in 55 at-bats that year.9

During spring training in 1946, Scales was watching the right-handed-hitting Gilliam flail at curveballs thrown by right-handed pitchers. “I couldn’t do anything with curveball pitchers,” Gilliam recalled in 1953. “I figured I’d lay back and wait for the fastball, but the pitchers in the Negro National League were smarter than me. They just threw me curves.”10

Having seen enough, Scales is purported to have yelled, “Hey, Junior, get over on the other side of the plate.”11 At 45 years old, Scales was old enough to be Gilliam’s father, and the moniker fit. Jim Gilliam was now Junior Gilliam.

Gilliam’s version of the exchange with Scales, however, suggested it was more like advice than a command. According to Gilliam, Scales approached him one day and asked, “You ever hit left-handed?”

Gilliam’s version of the exchange with Scales, however, suggested it was more like advice than a command. According to Gilliam, Scales approached him one day and asked, “You ever hit left-handed?”

“When I was a kid,” Gilliam replied. “I broke my right arm when I was 12 but I still played with the other fellows. I’d hold my bat in my left arm and the other one, it would be in a cast.”

“Then why not try it that way?” Scales said. “You’re not going any place this way.”12

“This way” was a reference to his unofficialposition in his first season with Baltimore: right-handed-hitting utilityman. “George told me that if I’d learn to switch-hit, I’d never go through life as a utilityman,”13 Gilliam said, smiling, to Bob Hunter for a 1964 Sporting News story. Ironically, Gilliam’s would be remembered as just that — a utilityman, appearing at every position except pitcher, catcher, and shortstop in his 14-year career with the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers.

If anyone in the Negro Leagues could mentor Gilliam on how to hit a curveball, it was Scales. Negro Leagues star and Hall of Famer Buck Leonard said, “George Scales knew how to hit it to a T! Josh Gibson knew it to a T. They hit a curveball farther than they hit a fastball. I saw George Scales hit a curveball four miles!”14

The transition to switch-hitting, while ultimately successful, was not easy. “When I first got over there I was afraid I couldn’t duck,” Gilliam remembered. “The first thing a switch-hitter’s got to know is to duck. But by the end of 1946 I was making the full switch all the time and I found I was able to follow the curve.”15

Butts believed Gilliam was actually a better hitter from the left side than the right. “Right-handed he was stronger, but he wouldn’t get as many hits,” Butts said. “When Scales switched him over, that’s when Junior started hitting.”16

Gilliam was added to the Elites roster and assigned to room with Joe Black. It was as unlikely a pairing as possible. Gilliam was a 17-year-old who had not graduated high school. Black was 22, had served in the military during World War II, and was on his way to earning a degree from Morgan State University. Gilliam was quiet and reserved. Black was outgoing and gregarious.

Neither man could have predicted how intertwined their lives would become. They would compete together with the Elites from 1946 to 1950. Their contracts would be purchased together by the Dodgers, and they’d spend part of 1951 together as teammates with Brooklyn’s Triple-A affiliate, the Montreal Royals. Black would join the major-league club in 1952 and win National League Rookie of the Year, which Gilliam would win in 1953. The two developed such a close friendship that Gilliam would become godfather to Joe’s son, Chico.

While Black might be credited with helping Gilliam grow from a teenager into a man, it was Scales’s instruction that transformed him into a legitimate baseball player. “Gilliam was a little fellow, very fast, didn’t have the strongest throwing arm, but quick,” Scales said years later. “And he wanted to play, that was the main thing.”17

Gilliam’s only known appearance in the first half of the 1946 Negro National League season occurred on Sunday, May 26, against the New York Cubans, when he entered a 4–4 game late at second base. No play-by-play exists for the bottom of the ninth, but the box score lists Gilliam as going 0-for-1. Luis Tiant Sr., throwing in his 16th season for the Cubans, pitched the ninth inning. It’s not known how Gilliam was retired.18 At the age of 17 years, seven months, and nine days, Gilliam had made his Negro National League debut.

Apparently thinking Gilliam was still too young, the Elites turned to two Negro Leagues veterans on June 4 to settle the infield, signing Sammy Hughes to play second and Willie Wells to play third. Hughes, recently released from the Army, was a Negro Leagues veteran, having played since 1930, mostly with Baltimore. Wells, who had begun the 1946 season with the New York Black Yankees, had made his rookie debut in 1924.

The Elites jumped out to a fast start in the second half, opening with a 4–1 record to occupy first place in the NNL. The team was paced by center fielder Henry Kimbro, hitting in the third spot and batting .366. Butts occupied the two hole, sporting a .313 batting average. Midseason signee Wells was batting .344 in the cleanup spot.19

Kimbro, a fellow Nashville native, also took it upon himself to mentor Gilliam. “Henry was a great leadoff man for the Elite Giants,” Gilliam recalled in 1964. “He told me the one thing I must learn was the strike zone. He wouldn’t swing at a ball an inch off the plate. That’s when I learned I couldn’t get good wood on a bad pitch.”20

As the 1946 season continued, it was clear the 35-year-old Hughes’ skills were diminished. Scales approached Gilliam with the idea of focusing only on second base, rather than utility. “We got to have a second baseman to go with Butts,” Scales said. “Sammy was all right, but the Army took it out of his legs. He can’t get around. You try it, Junior.”21

Butts told John Holway for his book Voices From the Great Black Baseball Leagues, “(Gilliam) really liked third base, but George Scales said, ‘No, you’d make a better second baseman.’ And I think he did. They said he had a weak arm, but he really could get rid of the ball and make those double plays. He wouldn’t stumble over the bag. Sometimes I’d say he wouldn’t even touch it.”22

Gilliam finally cracked the starting nine on July 16, lining up at second base and batting eighth with his friend and roommate Black on the hill.23 Gilliam went 0-for-3 with a sacrifice against Cubans pitcher Dave Barnhill. Gilliam’s name would not appear again in a box score until August 18, when, starting at shortstop to spell Butts, he went 1-for-3 with a double and a run scored against the Newark Eagles. His double, his first known Negro Leagues hit, came off Charles England, who surrendered all 12 Elites hits in 7 2/3 innings that day.24 England’s entire Negro Leagues career consisted of two games started, in which he allowed 17 hits and 13 runs in 9 2/3 innings.25

Gilliam soon became a fixture in the Elites lineup at second base, replacing Hughes, who would retire at season’s end. Gilliam started at second on August 27 against Tiant and the Cubans, batting second, a spot in the order that would become quite familiar to him over his career, and went 2-for-5.26 On September 2, he posted a 2-for-4 performance with a triple and an RBI in a 6–1 loss to the Homestead Grays.27

The highlight of 1946 for Gilliam occurred on September 13 as the Elites downed the Cincinnati Clowns of the Negro American League, 10–6. The Baltimore Sun wrote the next day that “Johnny Washington, Junior Gilliam, and Hem (sic) Kimbro were the big guns for the victors.”28 Gilliam went 4-for-5 with a double, a stolen base, and two runs scored. The reference to “Junior” in the September 14 Baltimore Sun article is the first known appearance in print of the nickname Scales bestowed upon Gilliam.

Four days after the end of the season, Gilliam turned 18. He had batted .304 in 46 at-bats for the Giants in 1946.29 Despite the limited playing time Gilliam received, Bob Luke concluded in his book on the Elite Giants, “Other than Gilliam’s and Butts’s performances, neither the Elites as a team nor any individual players had much to cheer about.”30

Junior Gilliam’s baptism into professional baseball was shaped by many great black players who never had a shot at the major leagues. To quote Negro Leagues star Ted Page, “George Scales made Junior Gilliam.”31

STEPHEN W. DITTMORE, PhD, is a professor of sport management and assistant dean at the University of Arkansas. A lifelong Dodgers fan born in Redondo Beach, California, Dittmore is co-author of a Sport Public Relations textbook now in its third edition and has more than 40 peer-reviewed publications. He has been a SABR member since 2018.

Sources

Baltimore Elite Giants photo: John W. Mosley Photograph Collection, Temple University Libraries

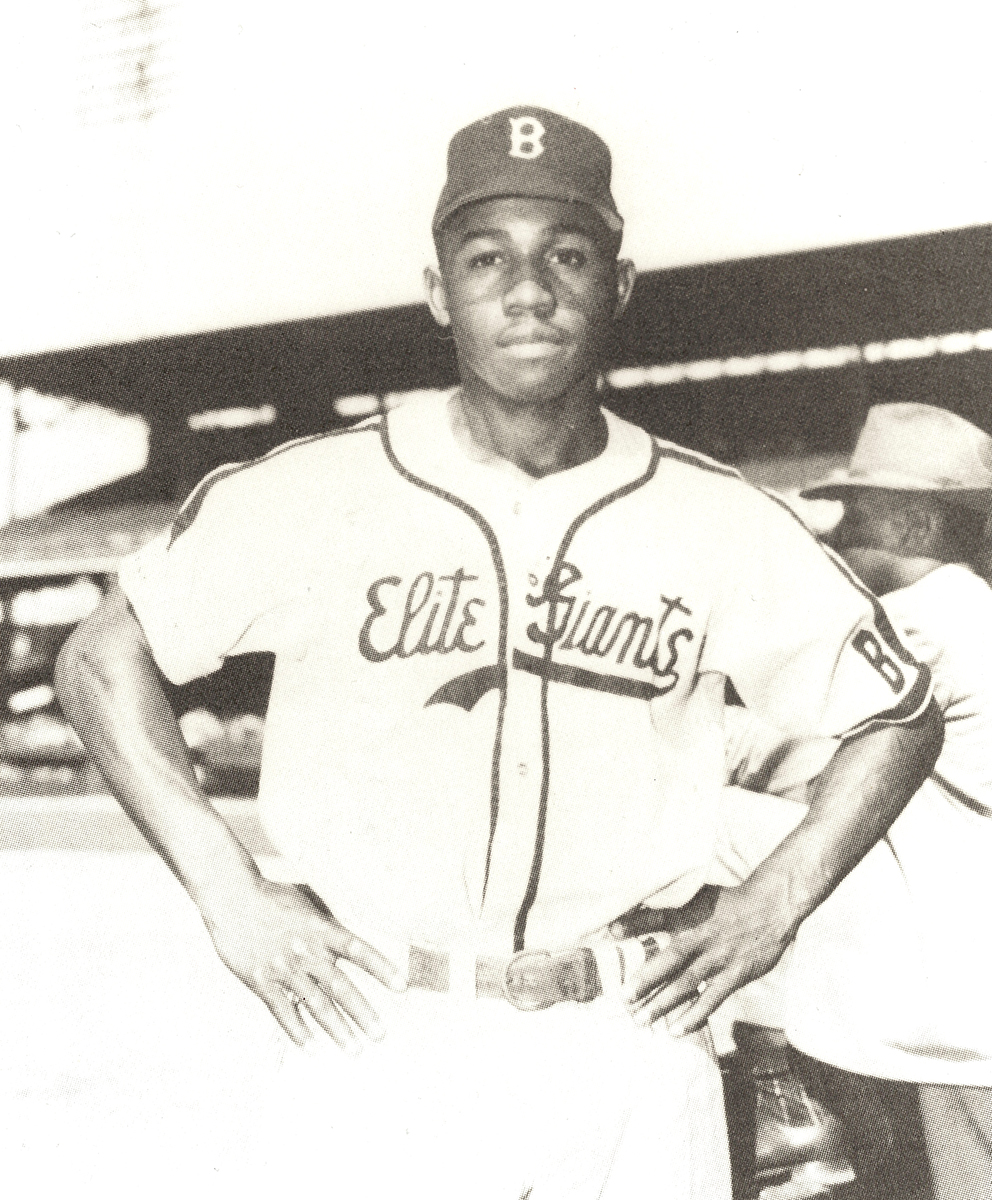

Junior Gilliam photo: NoirTech Inc. / Larry Lester

Notes

1 “Barnett Pilots Nashville Cubs,” Nashville Tennessean, March 31, 1946.

2 Some sources such as the Negro Leagues Museum list his middle name as Walter, but his 1918 draft card appears to bear his signature: George Louis Scales.

3 “George Scales,” Seamheads, accessed January 4, 2020, https://seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=scale01geo.

4 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 183.

5 Bob Luke, Baltimore Elite Giants, (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 39.

6 John Holway, Voices From the Great Black Baseball Leagues: Revised Edition, (New York: Da Capo Press, 1992), 333-4.

7 “George Scales: The Rifle Arm of Negro Professional Baseball,” Black Sports, May 1973, 32.

8 “Zapp New Elite Bat Star,” Baltimore Evening Sun, April 11, 1946.

9 “Frank Russell,” Seamheads, accessed January 4, 2020, https://seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=russe01fra.

10 “Meet Junior Gilliam! International League’s 1952 MVP,” Our Sports, June 1953, 57.

11 Martha Jo Black and Chuck Schoffner, Joe Black: More Than a Dodger, (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2015), 107.

12 “Meet Junior Gilliam!”

13 Bob Hunter, “Gilliam: Unsung, Unhonored—and Unsurpassed,” The Sporting News, April 4, 1964, 3.

14 Holway, Voices, 274.

15 “Meet Junior Gilliam!”

16 Holway, Voices, 335.

17 “George Scales: The Rifle Arm of Negro Professional Baseball,” Black Sports, May 1973, 32-33.

18 “Elite Giants Defeated by N.Y. Cubans, 7–4,” Baltimore Sun, May 27, 1946.

19 “Elite Giants defend loop lead against Cuban foe,” Baltimore Evening Sun, July 16, 1946.

20 Hunter, “Gilliam: Unsung.” 3

21 “Meet Junior Gilliam!”

22 Holway, Voices, 335.

23 “Elite Giants defeat New York Cubans, 5-3,” Baltimore Sun, July 17, 1946, 15.

24 “Elite Giants down Newark team twice,” Baltimore Sun, August 19, 1946, 13.

25 “Charles England,” Seamheads, accessed January 4, 2020, https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=engla01cha.

26 “New York Cubans top Elite Giants by 5-1,” Baltimore Sun, August 28, 1946, 14.

27 “Homestead Grays beat Elite Giants’ nine, 6-1,” Baltimore Sun, September 3, 1946, 19.

28 “Elite Giants defeat Cincinnati nine, 10-6,” Baltimore Sun, September 14, 1946, 11.

29 “1946 Baltimore Elite Giants,” Seamheads, accessed January 26, 2020, https://seamheads.com/NegroLgs/team.php?yearID=1946&teamID=BEG&tab=bat

30 Luke, Baltimore Elite Giants, 103.

31 “George Scales: The Rifle Arm.”