Good Optics: The 1955 Yankees Tour of Japan

This article was written by Roberta J. Newman

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

The Yankees arrive in Japan on October 20, 1955. (Rob Fitts Collection)

On Thursday, October 20, 1955, the New York Yankees and their entourage landed at Tokyo’s Haneda Airport to begin a three-week, 16-game goodwill tour of Japan. There, they were mobbed by kimono-clad young women bearing bouquets, an eager press corps, and a thousand devoted fans.1 The result was chaos, as children, autograph seekers,joumalists, businessmen, and advertisers of all stripes besieged the Yankees party.2 But the airport crowd was tiny compared with the throng lining the streets of Tokyo. An estimated 100,000 turned out to shower the motorcade—23 vehicles carrying the players and coaching staff, team co-owner Del Webb, general manager George Weiss, Commissioner Ford Frick, and accompanying wives—with confetti and ticker tape.3 They were also showered with rain from Typhoon Opal, but the weather, which caused significant damage and loss of life elsewhere in Japan, did little to dampen the crowd’s enthusiasm.4

The Yankees were not the only American visitors to arrive in Japan on that day. Former New York Governor and failed presidential candidate Thomas E. Dewey also landed in Tokyo on the Japanese leg of his world tour, with the stated aim of learning about Japan’s recent economic advances.5 In reality, Dewey’s aim was to spread pro-American Cold War propaganda to a new democracy still finding its political direction, a nation he called “one of the keystones to any sound system of freedom.”6 Dewey stayed but four days, his visit gamering little coverage in the English- language press. In contrast, the Yankees remained in the spotlight and on the pages of newspapers for the entirety of their visit. If influence can be measured by column inches, the Yankees’ impact on Japanese attitudes toward America far outweighed that of the political power broker.

Ten years before the Yankees arrived, Japan was thoroughly beaten, exhausted from fighting the “Emperor’s holy war.” Of the early postwar period, historian John W. Dower writes:

Virtually all that would take place in the several years that followed unfolded against this background of crushing defeat. Despair took root and flourished in such a milieu; so did cynicism and opportunism—as well as marvelous expressions of resilience, creativity, and idealism of a sort possible only among people who have seen an old world destroyed and are being forced to imagine a new one.7

For the Japan that greeted the Yankees, this new world had just begun to become a reality. The year 1955—Showa 30 or the 30th year of Emperor Hirohito’s reign by the Japanese dating system—marked the beginning of what would be called the Japanese Miracle, a period of unprecedented economic growth that lasted more than three decades.8 Ironically, war was the engine that drove the Japanese Miracle—the Cold War. In 1945, Japanese industry was crippled—almost one-third of its capacity had been demolished.9 With staggering unemployment rates among an educated labor force, combined with the country’s advantageous geographic location near Korea, China, and the USSR, Japan became an ideal place to establish new war-related industries and revive old ones.10 In a very real sense, Japanese manufacturers played an active part of what President Dwight D. Eisenhower would come to call the “military-industrial complex” in his 1961 farewell speech. Nevertheless, in 1955, relations between the United States and Japan were occasionally tense, the United States fearing that Japan, like India, would take a neutral position in the power struggle between it and the Soviet Union. It did not. Instead, it became one of the United States’s strongest allies.11 But the strength of that alliance was still wobbly as the two nations negotiated an ultimately successful trade deal, one that would see Japan’s entry into the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and become a player in the global economy.12

Though clearly not as delicate as treaty talks with international implications, negotiations to bring the Yankees to Japan were handled with care. In a very broad sense, these negotiations were a microcosm of the larger, far more complicated economic and political talks. In June, during the broadcast of a “good will talk” for the Voice of America, Yankees manager Casey Stengel, who had toured Japan in 1922 as part of an all-star outfit, let it slip that he might be returning. An anonymous source within the Yankees intimated that the team had, in fact, been discussing the possibility of a tour, as had several other clubs.13 Although there may have been other teams under consideration, it had to be the Yankees. As New York World Telegram and Sun sports columnist and Sporting News contributor Dan Daniel observed, “Information from U.S. Army sources says that baseball enthusiasm over there (in Japan) and rooting support for the pennant effort of the Yankees have achieved unprecedented heights.”14 Daniel, who covered the New York team, became the primary source of information regarding tour negotiations, though he did not cover the tour itself. But he was not the only sportswriter to weigh in. Writing in the Nippon Times, F.N. Mike concurred, noting, “The Yankees is a magic name here, where every household not only follows baseball doings in Japan, but also that in America. The Yankees, of all others epitomizes big-time baseball in the States, just as Babe Ruth, who helped to build up its name and who led the great 1934 All-Americans to Japan, represented baseball in America individually.”15 And not only were the Yankees the most recognizable and most popular American team in Japan, but their very brand meant “American baseball” and, by extension, America, to the Japanese, in the most positive sense.

Before the Yankees front office would consent to the visit, it required assurance that both governments were on board. More importantly, even after they were invited to tour by sponsor Mainichi Shimbun, the second largest newspaper in Japan, the organization would not begin to plan a tour without a formal invitation from the Japanese. The Japanese government laid down certain conditions, most specifically, that the visiting team would not be compensated. According to Daniel, “the proposition offers no financial gain to the club. Nor would any of the players receive anything beyond an all-expense trip for themselves and their wives.”16 In fact, it was absolutely essential that the team agree to forgo any type of payment. Writing in Pacific Stars and Stripes, columnist Lee Kavetski observed, “Each Yankee player is likely to be asked to sign an acceptance of non-profit conditions before making the trip.” Kavetski continued, “It is recalled an amount of unpleasantness developed from the Giants’ 1953 tour. Upon completion of the tour, some of Leo Durocher’s players complained that they had been misled and jobbed about financial remuneration. There was absolutely no basis for the complaint. And the beef unjustly placed Japanese hosts in a bad light.”17 This was hardly goodwill. Indeed, it was a public-relations disaster that extended into the realm of foreign relations. Kavetski noted, “As Joe DiMaggio, who has been to Japan twice, said to New York sports writer Dan Daniel, ‘Stengel’s players can perform a great service to baseball and to international friendship if they sign up for the trip even though there is no prospect for personal financial gain.’”18

Why did the bad behavior of a few American baseball players border on an international incident? On April 28, 1952, the San Francisco Peace Treaty, signed by 49 nations, including the United States and Japan, officially ended World War II. It also ended the Allied Occupation. As such, the Giants were guests in a newly sovereign nation trying to find its way and to establish its identity on a global stage. Tour sponsor Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan’s largest newspaper, promised to pay each player 60 percent of the gate of their final two games in Osaka in return for their participation. Unfortunately, the resulting figure was smaller than the players expected. Only 5,000 of the 24,000 who attended the first of those games actually bought tickets. As a result, each player was to be paid $331, in addition to “walking around money.” While this was no small amount—it translates to approximately $3,550 in 2021 dollars—it was nowhere near the $3,000 they believed they would net. Writing in Pacific Stars and Stripes, Cpl. Perry Smith noted, “The individual players did not appreciate the ‘giving away of the remaining 19,000 tickets and six team members refused to dress for the final contest.” Although they were eventually persuaded to take the field, they were not happy. This represented a significant cut in revenue for players accustomed to making good money during the offseason.19

Although the players thought they had a legitimate beef, their complaints did not play well in the press. To demand more was a public insult. Conditions in Japan had certainly improved by 1953, when the Giants toured, but they were far from ideal. Poverty and unemployment were still an issue, as was Japan’s huge national debt. That representatives of a wealthy nation demanded payment from the representatives of a newly emerging nation looked especially bad. That the players themselves were no doubt viewed as wealthy by individual Japanese could not have helped, either. It was essential that the Yankees not make the same mistake, treating their hosts as inferior and not worthy of due respect.

In 1955, US-Japanese relations were still a work in progress. While arrangements for the tour were being discussed, Japanese Deputy Prime Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu visited the United States for talks with Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. At a press conference, Shigemitsu, who simultaneously served as Japan’s foreign minister, “emphasized the desire of his government for a more independent partnership with the United States.” For Japan to make what Shigemitsu called “a fresh start,” he said, “we must talk things over frankly with the United States and see that the two governments understand each other.”20 Of course, Shigemitsu’s conference with Dulles had nothing directly to do with the goodwill baseball tour. But as he suggested, conditions laid down by a government seeking recognition of its independence had to be given their due. And given the timing, it would have been terrible optics were the insult to be repeated.

Ultimately, the Yankee players agreed and the tour was organized, but not before another major wrinkle had to be ironed out. Once Mainichi Shimbun offered its sponsorship, its chief competitor, Yomiuri Shimbun, countered with an offer to another team. Commissioner Frick was not having any of it. He responded negatively, announcing that simultaneous Japanese tours by two major-league clubs was out of the question—it would be one or none. Following their own delicate negotiation, competitors Mainichi and Yomiuri came to their own agreement. The two papers would sponsor tours by American clubs in alternating years.21

On August 23 George Weiss announced that the visit would proceed. Beginning with five games in Hawaii and ending with several more in Okinawa and Manila, the Yankees would leave New York shortly after the World Series on October 8 and planned to return on November 18. Included in the group of 64 travelers were many of the players’ wives, though some planned to stay behind in Hawaii. Among these wives were those of Andy Carey, Eddie Robinson, and Johnny Kucks, all of whom were on their honeymoons.22

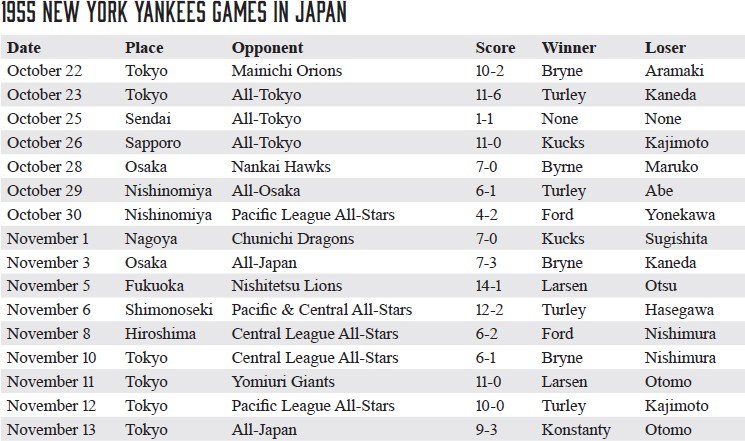

The schedule, which included games in Tokyo, Osaka, Kyushu, Sendai, Sapporo, Nagoya, and Hiroshima, was announced on September 24. Tickets, which went on sale on October 1 for the Tokyo games to be played at Korakuen Stadium, ranged in price from 1,200 yen (approximately $3.33) for special reserved seats, to 300 yen (approximately 83 cents) for bleacher seating. Games at other stadiums would top out at 1,000 yen (approximately $2.77).23 According to Japan’s National Tax Agency, in 1955 private sector workers earned an average annual salary of 185,000 yen (approximately $513). This was a great improvement from the poverty of the early postwar years. Indeed, it was approaching twice the annual salary that private sector workers earned in 1950.24 But even a ticket to the bleachers would have been a considerable reach for the average worker. As a result, it is safe to assume that the live spectatorship for the Yankees games would have consisted primarily of well-off Japanese as well as American servicemen. Other Japanese fans had to make do with newspaper coverage, radio and, in many cases, television.25 Realistically speaking, television receivers were extremely expensive, making individual ownership rare—in 1953, for example, even the least expensive receivers cost more than a year’s wages for the average Japanese consumer.26 But this didn’t mean that television was only for the wealthy. As in the United States, sets were placed strategically in front of retail establishments in order to draw customers. Far more common, however, was the institution of gaito terebi, plaza televisions, sets situated in accessible public spaces, which gave rise to the practice of communal viewing.27 This would have enabled many Japanese fans to watch the games.

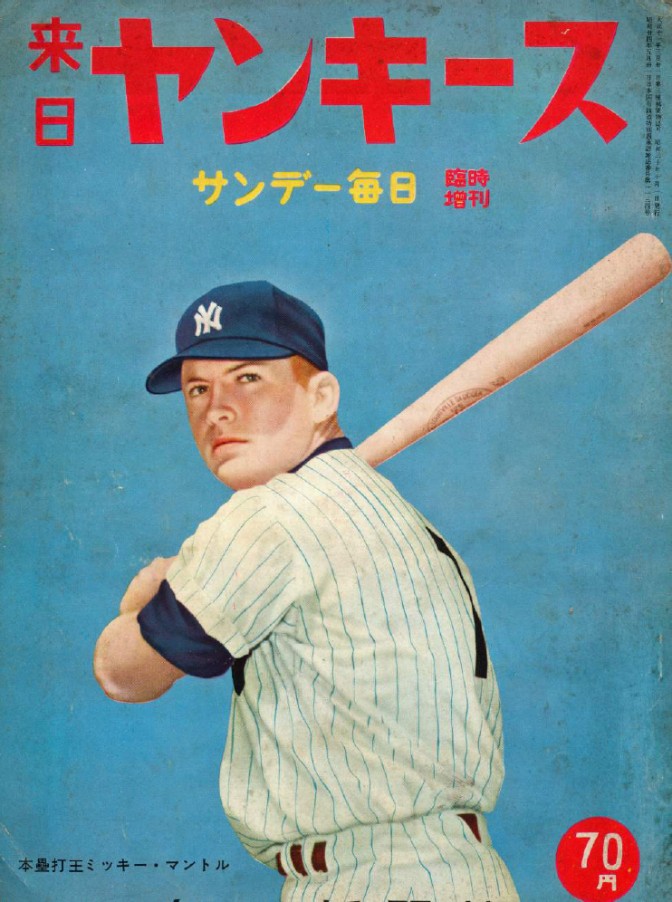

Cover of the 1955 Yankees’ Japan tour program featuring Mickey Mantle. (Rob Fitts Collection)

A Japanese poster promoting the series announced, “Unprecedented—the marvelous terrific team of our time—Champion of the Baseball World—New York Yankees—coming! Sixteen games in the whole country.”28 While not entirely accurate—the Yankees went on to lose the World Series to the Brooklyn Dodgers in seven games after the poster was printed—it did not matter to Japanese fans. Given the public response to the team’s arrival in Tokyo, the Yankees were, in fact, the “marvelous terrific team” of l955.

That the series had a purpose beyond “goodwill” was publicly stated by Vice President Nixon, speaking on behalf of President Eisenhower, on October 12. Eisenhower had, in fact, been involved with the planning, according to Del Webb. Prior to arranging the tour, Webb had discussed its potential benefits with the president, Secretary Dulles, and General Douglas MacArthur, former commander of the Allied powers in Japan. “I asked the president last summer if he thought a trip by the Yankees might help bring the American and Japanese people closer to each other,” said Webb. “He said it would.”29 So it was no surprise that Nixon made a statement, addressing Commissioner Frick, expressing the president’s best wishes. Nixon wrote, “Appearances in Japan by an American major league baseball team will contribute a great deal to increased mutual understanding between the people of the United States and the people of Japan, and thus to the cause of a just and lasting peace, which demands the continued friendship and cooperation of the nations of the Free World.”30 It was up to the Yankees, Nixon implied, to help cement the US-Japanese alliance, assuring that Japan would come down on the side of “freedom” rather than neutrality in the ongoing struggle against the unfree Soviet bloc. Of course, the vice president’s statement was a clear example of the inflated rhetoric of Cold War propaganda. But the message was unavoidable. Public relations played an essential role in geopolitics, and this tour was, above all else, an exercise in public relations.

Having fared well on their Hawaiian stop, winning all five games against a mixture of local teams and armed forces all-stars, and having survived their mobbing at the airport, the Yankees began their hectic schedule. The sodden but jubilant welcome was followed by a series of events, receptions, and press conferences. The next day, the team worked out while Stengel, who would serve as the face of the club, and Weiss attended a luncheon at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club. Lest it be thought that the tour consisted only of propaganda, the proceedings included their fair share of frivolous fun, which was also covered in the press. At the club, Stengel was presented with a gift—a large box, labeled “For 01’ Case.” According to the Nippon Times, “Stengel stood patiently by while bearers deposited the box at his feet. Then, lo and behold, a pretty girl in a kimono crashed through the wrapping pounding her fist into a baseball glove in the best tradition of the game.”31 Sensing an opportunity to get in on the act, Weiss “went through the motions of putting the girl’s name to a contract.” In what might, in twenty-first-century terms, be considered in very bad taste, Weiss asked her how much she wanted. But under the circumstances, Weiss’s actions were just part of the fun. Nevertheless, Stengel took a moment to emphasize the true nature of the tour. The Yankees were in Japan “on a serious mission of good will.”32

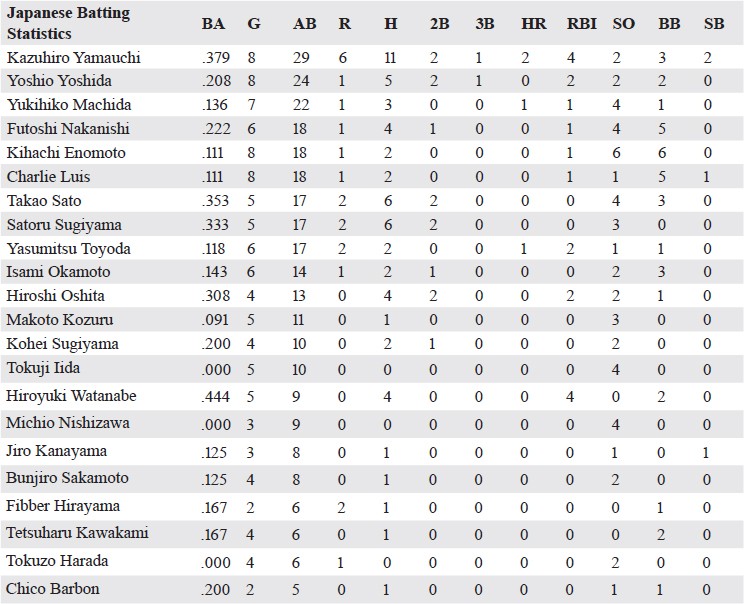

It would be nice to say that the first game, held on Saturday, October 22, went off without a hitch. But rarely does this happen when there are so many moving parts. This time, Opal did more than just soak a parade. The typhoon caused a postponement of Game Five of the Japanese championship series between the Nankai Hawks and the Yomiuri Giants, which was scheduled to be played at Korakuen Stadium on Friday. As a result, the Yankees contest had to be moved to the evening to accommodate both games. A smaller crowd than expected—35,000, about 5,000 shy of a capacity crowd—turned out to see the Yankees make quick work of the Mainichi Orions, beating the Japanese team 10-2.33 After Kaoru Hatoyama, the wife of the prime minister, threw out the first pitch—the very first wife of a head of state to do so at a major-league game, exhibition or otherwise—fans and dignitaries were treated to a 10-hit barrage by the Yankees, including two home runs and a triple by rookie catcher Elston Howard. The Orions countered with seven hits, but committed a costly first-inning error in their loss. The crowd, which included Thomas E. Dewey and his wife, was not disappointed.34

Baseball, however, never completely supplanted diplomacy, as Prime Minister Hatoyama greeted the Yankees, Frick, and their entourage at a reception. Among the many photo ops, one stood out. Hatoyama, having been presented with a Yankees hat by Stengel, became the first Japanese prime minister to wear a baseball cap.35

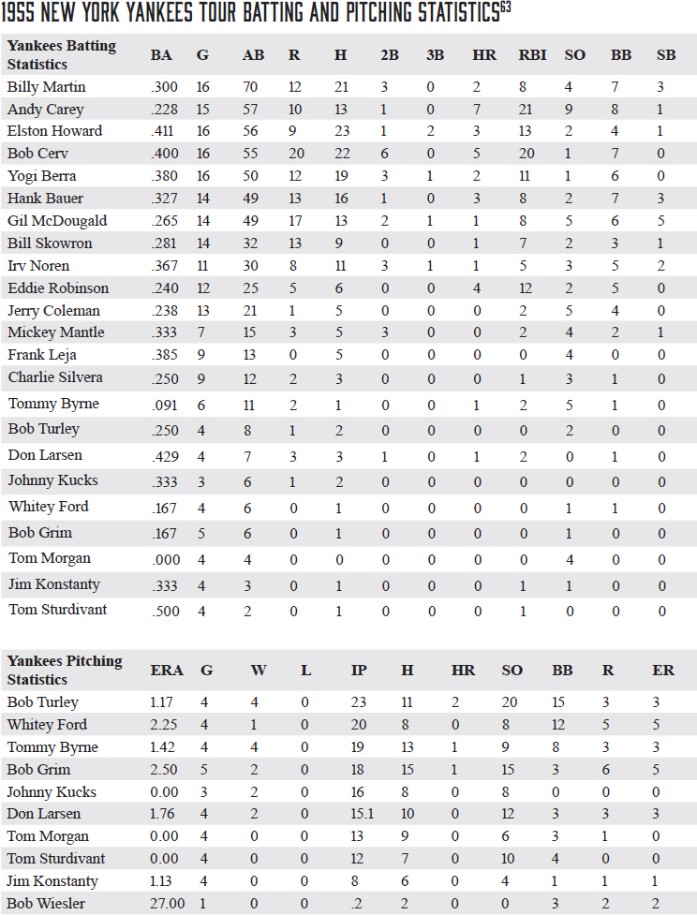

The Yankees were once again victorious in the second game at Korakuen Stadium, this time defeating All-Tokyo (a team composed of Pacific and Central all-stars) 11-6 in front of a capacity crowd. A ninth-inning grand slam by first baseman Eddie Robinson off the Japanese Central League’s Rookie of the Year, Kazunori Nishimura, sealed the victory. This time, the Japanese players’ bats were not quiet. All-Tokyo managed seven hits against Bob Turley and Bob Grim. Only Mickey Mantle underperformed. Fans, perhaps unreasonably, expected big things out of the injured Mantle, who had played only part time in the World Series, a few weeks earlier. Mantle struck out three times in the second game, after whiffing once during a pinch-hitting appearance in the first game.36

With the third game in Tokyo postponed until later in the trip, the Yankees moved on to Sendai, 304 kilometers to the north on Japan’s east coast. As in Tokyo, they were mobbed. Greeted by another throng, their motorcade tied up traffic for two hours en route from their hotel to Miyagi Stadium, where once again they went head-to-head with All-Tokyo.37 Ending New York’s winning streak, the Tokyo squad played to a 1-1 tie, despite the fact that they had but one hit. But the Yankees also committed an error, allowing All-Tokyo to score its run.38 From Sendai, both teams flew to Sapporo, located on Hokkaido, the northernmost main island, where they played for an overflow crowd of 30,000. Returning to form, Mantle finally got going, hitting two doubles to the delight of the spectators, in the Yankees’ 11-0 rout of the all-stars.39

Another huge crowd, complete with its own ticker-tape parade and its own storm, greeted the Yankees in Osaka, in the southwestern part of the main island. There the American club took on the Nankai Hawks. Like the Yankees, the Hawks had been unable to win a championship, having fallen to Yomiuri Giants in the 1955 Japan Series. Japan’s second-best team fell to America’s as well, losing in a 7-0 shutout. The crowd was unusually sparse for this contest, for reasons beyond the control of both teams. Once again, rain interfered. Only 15,000 fans came out to see the game.40

There was no such paucity of spectators for the second game in the Osaka area, where 30,000 turned up at Nishinomiya Stadium on October 29 to see the All-Osaka nine lose 6-1 as the Yankees amassed 16 hits. Bob Cerv, substituting for Mantle, thrilled the crowd with a “tremendous 430-foor homer.” Once again Turley and Grim performed masterfully against the best players in the region.41

The next day Cerv homered again and collected all four of the Yankees’ RBIs against the Pacific League All-Stars. Cerv went on to double in the eighth, once again scoring Martin with the final run. The All-Stars scored as well—once in the seventh inning and once in the eighth—but it was not enough to put the Japanese team over the top.42 Had the Yankees done nothing more than entertain Japanese baseball fans in Osaka, it most likely would have been sufficient to gamer goodwill and burnish America’s reputation in the eyes of the Japanese. But they were teachers as well as performers. The Yankees held a clinic for more than 200 participants. Coach Bill Dickey worked with the local players on catching techniques, while Jim Turner tutored them on pitching. Gus Mauch, the Yankee trainer, held his own clinic as well.43 According to Tokyo journalist N. Sakata, who had recently traveled to the United States to cover an international tournament and the World Series, the Yankees’ primary role was to provide instruction to their Japanese opponents. Writing in The Sporting News, Sakata observed, “(The Yankees’) way of sliding is something we have to learn. Some of the Yankee players tell me that the Japanese way of defending bases is very dangerous to themselves. The Japanese players are not accustomed to the American way of base-sliding.”44

Next on the itinerary, the Yankees flew to Nagoya to play the Chunichi Dragons, before returning to Osaka. A crowd of 33,000 came out to see the New Yorkers face Dragons ace Shigeru Sugishita. The Yankees touched up Sugishita for seven runs, including another home run by Robinson and doubles by Kucks and Yogi Berra, while the Dragons managed just three hits and no runs off Kucks and Tom Sturdivant.45 Conspicuously absent was the underperforming Mantle. Injury was not the cause. The Yankees erstwhile slugger left Japan early to attend to his ill wife, Merlyn, who was expected to give birth imminently.46 Despite Mantle’s anemic performance in part-time play, Japanese fans were disappointed. They had been holding out hope that he would break out of his slump and that they would be there to witness it.47

November 3, a Japanese holiday celebrating the birthday of the Meiji Emperor (1852-1912), who both modernized and militarized the country, was another banner day for the Yankees. Drawing one of the largest crowds in Japanese baseball at the time, the Yankees and All-Japan played in front of 70,000, paying an average of 720 yen each, at Koshien Stadium. Once again, the Yankees emerged victorious, defeating their opponents by a score of 7-3, behind a home run from Billy Martin, who may have made the crowd forget Mantle’s absence.48

But the real victor here was US-Japanese relations. In Osaka the Yankees made a move that, as Red McQueen, writing in The Sporting News, observed, “solidified the importance of their visit as good-will ambassadors of the United States and Organized Ball.” Before he, too, left Japan, Weiss spoke enthusiastically about the quality of Japanese baseball, appointing Henry Tadashi “Bozo” Wakabayashi, coach of the Tombow Unions of Japan’s Pacific League, an official Yankees scout. Said Weiss, “As the one who inaugurated the Yankee scouting and baseball school system, I have long wanted to institute an exchange between the Japanese pro circuits and the leagues in America. We would be interested in players who stood out and we would be very happy if we found one. However, we would not sign a Japanese player merely for publicity.”49 It is possible that Weiss was being honest. Still, it would take more than four decades for the Yankees to sign their first Japanese player, Hideki Irabu, in 1997. A genuine desire to sign a Japanese player does not seem to have been the real aim of Wakabayashi’s appointment. It was, in fact, publicity, but not for the Yankees. In a sense, it represented a public recognition of the emerging status of Japanese baseball in international sports, and, by extension, a representation of Japan’s independence and the type of new understanding between the American and Japanese people. While it may not have been specifically what Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Shigemitsu had in mind, it signaled the type of respect that Shigemitsu expected would be extended to Japan by the United States.

From Osaka, the Yankees once again boarded a plane, this time for Fukuoka, on the southernmost of the major Japanese islands, Kyushu, to play the Nishitetsu Lions. In the eyes of an unnamed sports- writer for the Nippon Times, the Yankees “annihilated” the Lions, 14-1. Perhaps this was not the best language to use, given Fukuoka’s proximity to Nagasaki, but the lede on the sports page of an English-language Japanese newspaper was not noteworthy enough to cause a stir. Once again, Robinson homered—this time a grand slam. So did Hank Bauer, Andy Carey, Bob Cerv, and pitcher Don Larsen, who hit .146 during the regular season. The Lions managed five hits. A single by outfielder Hiroshi Oshita drove in Akinobu Kono for the team’s only run.50 Then it was on to Shimonoseki, at the very tip of the main island, not far from Fukuoka. Once again, the Americans poured it on, touching up the Pacific-Central All-Stars pitching for 19 hits and 12 runs. All-Stars shortstop Yasumitsu Toyoda managed a two-run homer off Turley in the third inning for the Pacific-Central team’s only runs.51

The tour’s last stop before returning to Tokyo for the final series of games was Hiroshima, where the Yankees defeated the Central All-Stars, 6-2. This time the New York squad had to come from behind to defeat its opponents, who jumped out to an early 2-0 lead.52 Perhaps not surprisingly, the game, not the city’s history, was the emphasis of this visit. By 1955 Hiroshima had rebounded. The city played a significant role in the Japanese Miracle, becoming a center for weapon manufacturing and procurements during the Korean War.53 Nevertheless, concerns about the long-term effects of radioactive fallout remained.

While the Yankees were in Japan, a small group from Hiroshima were visiting New York, but for different reasons. An item in the Nippon Times about a member of the Yankees traveling party tells a story not included on the sports page. Toshio Ota, a transplanted Hiroshima resident living in New York, accompanied the team on its trip. Ota reported to the newspaper about the welfare of the Hiroshima Maidens.54 A group of 25 girls and young women—hibakusha, survivors of the atomic bombs—who had been badly disfigured in the attack, were taken to New York under the auspices of the American Friends Service Committee and several other organizations, with the help of Saturday Review editor Norman Cousins, to undergo reconstructive plastic surgery. Both the patients and physicians came to be seen as symbols of developing understanding and goodwill between the United States and Japan, as did the Yankees on their tour, though in a far more important fashion. Moreover, the Maidens’ treatment cast a public spotlight on the devastation of nuclear warfare.55

On November 10 the Yankees returned to Tokyo for four games, three that had been previously scheduled and the rescheduled contest against the Yomiuri Giants. Once again facing the Central League AllStars, the Yankees continued their streak against Japan’s best, winning 6-1. And once again they came from behind, this time after Yoshio Yoshida tripled, scoring on a fielder’s choice. In fact, the Yankees were held hitless over the first three innings by pitcher Kazunori Nishimura but broke out in the fourth with four runs.56 The streak continued the next day, as the Yankees rode roughshod over the Japanese champions, shutting out the Giants 11-0. As in the previous game, the Yankees were held scoreless, though not hitless, until the fourth inning. Then the tide turned. They scored three in the fourth and eight in the sixth. Despite a triple by Morimichi Iwashita and doubles by Takashi Iwamoto and Andy Miyamoto, a Hawaiian member of the Giants squad, the Tokyo effort turned into an exercise in futility.57

Korakuen Stadium also hosted the final two games of the tour, as the Yankees played the Pacific League All-Stars and the Japan All-Stars. Neither the first game against the Pacific team nor the two that preceded it drew huge crowds, but attendance was still substantial. Some 20,000 turned out to see the Yankees shut out their Japanese opponents yet again, this time by 10-0, outhitting the All-Stars 12 to 4.58 Not surprisingly, the final game, played on November 13, drew quite well. According to the Nippon Times, 35,000 cheering fans joined the Yankees, “saying say- onara.” Surprisingly, unlike 14 out of the previous 15 contests, the Tokyo outfit outhit the Yankees, 8 to 7. Yogi Berra homered twice in the Yankees’ 9-3 win. But as was true for the other 15 games, the spectators had not come to see the Japanese win, but rather, to see the American celebrities do what they did best.59

Still, there were doubts that the Yankees had given the games their all. After the final contest, Tokuro Konishi, a former professional manager, announced to his radio audience that the Yankees had played only to 70 to 80 percent of their ability, so as not to make the local players look too bad. A bemused Stengel replied, “Our players gave their best to win and I’m proud of the fine impression they made.” American League umpire John Stevens, who worked the whole series, concurred. “We had a wonderful trip,” noted Stengel. “The fans treated us swell.”60

After a final day packing and shopping in Tokyo, the Yankees departed for Okinawa, then a United States protectorate, and the Philippines. Unlike the 1953 Giants tour, the Yankees’ goodwill trip was an unmitigated success. Indeed, even the New York Times, which had paid it scant attention, declared it so.61 Red McQueen, writing in the Honolulu Advertiser, agreed. “This morale, patriotic and goodwill stuff can be stretched a bit too far, but in the case of the recent visit of the New York Yankees and their present tour of Japan and the Philippines, it is one of the most diplomatic excursions in the history of sports,” opined McQueen. “Except for the explicit purpose of spreading goodwill between the respective nations, it is doubtful that a venture of this nature could ever have materialized.”62 Whether or not the tour had a direct effect on US-Japanese relations, it provided great optics. It was a public-relations coup. While the relationship between the two nations, one already a global superpower, the other on its way to becoming a major player in the world economy, would take a few more years to form into a solid alliance, Japan finally came down firmly on the side of the United States in the Cold War. The Yankees’ goodwill tour provided a vision of what cooperation between the two countries might look like. By respecting Japan’s newfound sovereignty and serving as exemplary guests—even Martin, Ford, and Mantle, while he was there, seem to have behaved themselves—the New York Yankees and major-league baseball as a whole participated in what might be called their own Japanese miracle.

ROBERTA J. NEWMAN is a clinical professor of liberal studies at New York University. Her work focuses on the many intersections between baseball and popular culture. She is co-author of Black Baseball, Black Business: Race Enterprise and the Fate of the Segregated Dollar (2014), and author of Here’s the Pitch: the Amazing, True, New, and Improved Story of Baseball and Advertising (2019), as well as numerous articles on these and other topics. Currently, she is at work on a project dealing with Japanese baseball, manga, and cultural identities.

NOTES

1 “Mobbed at the Airport,” Nippon , October 21, 1955: 1.

2 Bob Bowie, “Thousands Greet Yankees in Tokyo,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 21, 1955.

3 “Royal Welcome Greets the Yankees,” Nippon Times, October 21, 1955: 1.

4 “5 Killed, 22 Injured as Opal Hits Kinki,” Nippon Times, October 21, 1955: 1.

5 “Dewey to Inspect Japan’s ‘Strides’,” Nippon Times, October 21, 1955: 1.

6 “Dewey to Inspect Japan’s ‘Strides’.”

7 John W. Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (New York: W.W. Norton, 1999), 44.

8 “Japanese Miracle,” Farlex Financial Dictionary, 2009, accessed November 27, 2021, https://financial-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Japanese+Miracle.

9 Aaron Forsberg, America and the Japanese Miracle: The Cold War Context of Japan’s Postwar Economic Revival, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 17.

10 Forsberg, 27.

11 Forsberg, 42.

12 “Japan and the WTO,” World Trade Organization, accessed November 27, 2021, https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/japan_e.htm.

13 “Yankees May Visit Japan This Autumn,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, June 3, 1955: 24.

14 “Bombers ‘Quite Certain’ to Play Here This Fall,” Nippon Times, August 1, 1955: 4.

15 F.N. Mike, “Times at Bat,” Nippon Times, July 23, 1955: 5.

16 “U.S., Japan Reported Backing Post-Season Tour by the Yankees,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, June 18, 1955: 24.

17 Lee Kavetski, “Chotto Matte, Tourists,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, August 3, 1955: 22.

18 Kavetski.

19 Cpl. Perry Smith, “Giants Net $331 Each, Expected $3,000,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 10, 1953: 14.

20 “Shigemitsu Says Japan Must Move Toward Complete Independence,” Washington Post and Times Herald, August 27, 1955: 1.

21 Dan Daniel, “Plans Shaping Up for Yankee Team to Play in Japan,” The Sporting News, August 3, 1955: 1-2.

22 Robert W. Bowie, “Tokyo Sets Welcome for Yankees,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 21, 1955: 26.

23 “Visiting Yanks to Open Against Mainichi Club,” Nippon Times, September 24, 1955, 8. The exchange rate, as established by the Bretton Woods system, was set at a fixed rate of 360 yen per dollar between 1947 and 1971. “Timeline: Milestones in the yen’s history, Reuters, accessed December 3, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yen/timeline-milestones-in-the-yens-history-idUSTRE49QiAN20o8i027.

24 Statistical Survey of Actual Status for Salary in the Private Sector, National Tax Agency in “Changes in Wage-Workers Salaries in Japan, 1950-2013,” accessed December 4, 2021, https://nbakki.hatenablog.com/entry/Changes_Wage-W0rkers_Salary_1950-2013.

25 “Radio and TV Highlights,” Nippon Times, October 22,1955: 4.

26 Jayson Makoto Chun, A Nation of a Hundred Million Idiots? A Social History of Japanese Television, 1953-1973 (New York: Routledge, 2006), 55.

27 Chun, 61.

28 “‘World Champions’—It Says Here,” The Sporting News, October 12, 1955: 18.

29 “Webb Sees Japanese in Majors Soon,” Nippon Times, November 1o, 1955: 5.

30 “Nixon Extends Yanks Best Wishes on Trip,” Nippon Times, October 13, 1955: 5.

31 David M. Jampel, “Casey Finds Shortstop at Press Club Lunch,” Nippon Times, October 22, 1955: 5.

32 Jampel.

33 Red McQueen, “Yankee Crowds Total 135,000 for First Four Games in Japan,” The Sporting News, November 2, 1955: 7.

34 “Yanks Cop Debut,” Nippon Times, October 23, 1955: 1, 2.

35 “Yanks Cop Debut.”

36 “Yanks Batter Stars, 11-6,” Nippon Times, October 24, 1955: 3.

37 “Sendai Pours Out to Greet Yankee Team,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 26, 1955: 24.

38 “Tokyo All-Star Nine Ties Yankees 1-1, Break Stengelmen’s 7-Game Streak,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 26, 1955: 24.

39 “Yanks Hand Japan Nine 11-0 Setback,” Nippon Times, October 27, 1955: 5.

40 “Yanks Blank Hawks,” Nippon Times, October 29, 1955: 9.

41 “Bombers Beat All-Osaka,” Nippon Times, October 30, 1955: 5.

42 “Yanks Beat All-Pacific, 4-2,” Nippon Times, October 31, 1955, 5; Red McQueen, “Yankees Name Scout to Cover Japanese Loops,” The Sporting News, November 9, 1955: 9.

43 “200 Attend First Yankee Clinic,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 30, 1955: 24.

44 “‘Yankees Trying to Teach Us,’ Says Japanese Scribe,” The Sporting News, November 9, 1955: 9.

45 “Yanks Blank Dragons, 7-0,” Nippon Times, November 2, 1955: 5.

46 “Mickey Mantle Leaving for U.S.,” Nippon Times, November 1, 1955: 5.

47 >Red McQueen, “Yankees Name Scout to Cover Japanese Loops,” The Sporting News, November 9, 1955: 9.

48 McQueen, “Yankees Name Scout to Cover Japanese Loops.”

49 McQueen, “Yankees Name Scout to Cover Japanese Loops.”

50 “Yankees Blast Lions, 14-1,” Nippon Times, November 6, 1955: 5.

51 “Yanks Slam Stars, 12-2,” Nippon Times, November 7, 1955: 5.

52 “Yankees Win Again, 6-2,” Nippon Times, November 9, 1955: 5.

53 “II Period of High Economic Growth,” Hiroshima for Global Peace, accessed December 5, 2021, https://hiroshi- maforpeace.com/en/fukkoheiwakenkyu/vol1/1-36/.

54 “With Yankees,” Nippon Times, October 25, 1955: 3.

55 Aron D. Wahrman, “Caring for the Hiroshima Maidens,” Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons, accessed December 5, 2021, https://bulletin.facs.org/2020/03/caring-for-the-hiroshima-maidens/.

56 “Yanks Beat Central Stars, 6-1,” Nippon Times, November 11, 1955: 8.

57 “Yanks Wallop Giants,” Nippon Times, November 12, 1955: 5.

58 “Yankees Rout Pacific Stars,” Nippon Times, November 13, 1955: 10.

59 Yanks Trip Stars, 9-3,” Nippon Times, November 14, 1955: 5.

60 “Stengel Disclaims Yanks Held Back,” Nippon Times, November 14, 1955: 5.

61 “Yankees’ Tour Successful, New York Times Comments,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 18, 1955: 24.

62 Red McQueen, “Yankee Tour Truly a Patriotic Gesture,” The Sporting News, October 26, 1955: 15.

63 Listed Japanese players have a minimum of five at-bats, three innings pitched, or a decision. Yoshikazu Matsubayashi, Baseball Game History: Japan vs, U.S.A. (Tokyo: Baseball Magazine, 2004), 92; Nippon Professional Baseball Records, https://www.2689web.com/nb.html.