Greenberg Gardens Revisited: A Story about Forbes Field, Hank Greenberg, and Ralph Kiner

This article was written by Ron Backer

This article was published in Fall 2022 Baseball Research Journal

In 1947, the Pittsburgh Pirates installed an inner fence in a portion of Forbes Field, reducing the distance down the left field line of the ballpark by 30 feet. The purpose of the fence was to assist the team’s newest acquisition, Hank Greenberg, in his ability to hit home runs. The area between the new fence and the outer wall became known as Greenberg Gardens.1

Forbes Field is long gone, having been demolished in 1971. Greenberg Gardens is even longer gone, having been removed before the beginning of the 1954 season. But the memory of Greenberg Gardens lingers, for being an unusual attempt to adjust the dimensions of a baseball playing field to benefit a single batter. The following is the story of Greenberg Gardens, the ballpark, Forbes Field, the intended beneficiary of Greenberg Gardens, Hank Greenberg, and its unintended beneficiary, Ralph Kiner.

FORBES FIELD

The Pittsburgh Pirates played their first game at the newly built Forbes Field on June 30, 1909. The ballpark was erected in the Oakland section of the City of Pittsburgh, on the edge of Schenley Park; 30,338 fans attended the game, only to see the Cubs beat the Pirates, 3–2.2

Built of concrete and steel rather than the traditional wood, the cost of the new ballpark was about one million dollars.3,4 The park received very good reviews upon its opening. The Pittsburgh Gazette Times wrote, “Forbes Field is the marvel of the world.”5 Ring Lardner, writing in the Chicago Tribune, extolled the virtues of the setting of Forbes Field in Schenley Park, calling it a “beautiful new field.”6 The 1910 Reach Baseball Guide said, “For architectural beauty, imposing size, solid construction and public comfort and convenience, it has not its superior in the world.”7

Despite these accolades, several changes were made in the configuration of the playing dimensions of Forbes Field over the years, many of which affected the left-field home-run distance. In May 1911, less than two years after Forbes Field opened, home plate was moved about 26 feet back toward the grandstand and the field was shifted slightly towards right field, enlarging the playing surface and increasing the distance down the left field line to 360 feet from its original distance of about 306 feet.8 In 1925, a new scoreboard was erected in left field, near the foul line but in fair territory, causing many long balls hit in that direction to become doubles rather than home runs.9 In 1930, home plate was moved five feet further from left field (and the foul lines shifted slightly), increasing the distance down the left field line to 365 feet.10

Given these many changes in the left-field dimensions, the addition of Greenberg Gardens in 1947 was not that unusual. However, Greenberg Gardens turned out to be very controversial. Part of the issue was aesthetics; the other was its effect on home runs hit in the ballpark.

HANK GREENBERG

Henry Benjamin (“Hank”) Greenberg was born in New York City on January 1, 1911, to David and Sarah Greenberg, both Jewish immigrants from Romania. Hank excelled at multiple sports in high school, including basketball and baseball. After high school, he received interest from several major league teams. In 1929, Greenberg signed with the Detroit Tigers and was brought up to the big leagues in 1933.11 By May, he had become the regular first baseman of the Tigers. The following year, 1934, was his breakout season—he hit 26 home runs and had 139 RBIs. However, he is most famous for not playing that year on Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the year in the Jewish religion.12

In 1935, Greenberg led the American League in home runs, and was voted the Most Valuable Player. In his most famous season, 1938, Greenberg almost broke Babe Ruth’s season home run record of 60, finishing with 58 home runs. Greenberg had good seasons in 1939 and 1940 (winning the Most Valuable Player award again in 1940), but thereafter he was off to war, missing most of four seasons during World War II, and not returning to his team until July 1, 1945. Despite the long layoff, Greenberg hit a grand slam in the top of the ninth inning on the last day of the season to send the Tigers to the World Series.

At the start of the 1946 season, Greenberg was 35 years old and his physical condition was deteriorating. During the season, his lower back—which had bothered him in his military days— continued to nag him. His batting average, which had been consistently over .300, dropped significantly, even though in the end, he led the American League in both home runs and RBIs. Nevertheless, Detroit was interested in dumping Greenberg’s high salary and when an erroneous off-season report in The Sporting News led Walter O. Briggs, the owner of the Tigers, to believe that Greenberg wanted to play for the Yankees, he grew determined to get rid of the slugger.13 On January 18, 1947, the Tigers sold Greenberg’s contract to the Pirates.14

The deal was a big risk for Pittsburgh, as they were out the money paid to Detroit for Greenberg’s contract even if Greenberg did not actually come to Pittsburgh to play. At the time, Greenberg was seriously contemplating retirement—in fact, he told the Pirates in February that he was retiring.15 However, the Pirates were not dissuaded. New owner John Galbreath spent three days trying to convince Greenberg to change his mind. He even enlisted the help of another new Pirates owner, Bing Crosby.16 They addressed Greenberg’s two main objections: money and the long left-field dimension of Forbes Field. Galbreath offered to pay Greenberg $100,000 per year, making him the highest paid player in the game, and told Greenberg that the Pirates were already contemplating moving the bullpens to left field. The change would reduce the distance down the line to about the same as it was at Briggs Stadium in Detroit, which had been Greenberg’s home field for years. With the promises and cajoling, Greenberg finally agreed to become a Pittsburgh Pirate.17

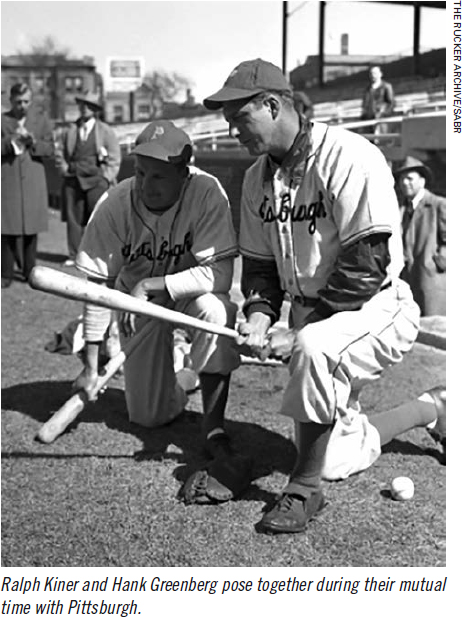

In the end, Hank Greenberg played only one season in Pittsburgh, hitting only 25 home runs, despite the installation of the shorter fence. Lingering injuries caused him to miss several games that year. Greenberg retired at the end of the season.18

RALPH KINER

The person who benefitted the most from Hank Greenberg’s one year in Pittsburgh was Ralph Kiner. Kiner led the National League in home runs for the six full seasons while playing in Forbes Field with Greenberg Gardens. With his home-run title in 1946, Kiner led the National League in home runs for seven consecutive seasons, a record that still stands today.19 More importantly, Greenberg immediately took Kiner under his wing and helped him with his hitting and attitude toward the game.

Ralph McPherran Kiner was born on October 27, 1922, in Santa Rita, New Mexico. After his father’s death when Ralph was only four, the family moved to California where, with the help of a neighbor, he learned the game of baseball. As he grew up, he played baseball in local sandlot games and in high school. He also played for the Junior Yankees, an amateur team sponsored by the New York Yankees. At the time, there was an unwritten agreement among major league baseball clubs that players with major-league-sponsored junior teams would be signed by the parent organizations when they became old enough to play professionally.20 However, once Kiner graduated from high school, the Pirates made a strong bid for his services, convincing him that he had a better chance of making it to the majors faster with the Pirates than with the Yankees. Kiner signed with the Pirates in 1940.

Kiner’s baseball career started in the minor leagues in 1941, but after two seasons, his playing career was interrupted by his service in the Navy Air Corps. Returning to the game for the 1946 season, Kiner expected to be sent to the minors, but after a good spring training, he was promoted to the big club where he had a very good rookie season. He led the National League in home runs with 23, equaling the Pirates club record set in 1939 by Johnny Rizzo.21 He also had 81 RBIs.

When Hank Greenberg arrived the following year, he started working with Kiner on his hitting in spring training. They often worked after the official practice sessions had ended, and then before games once the regular season commenced. He moved Kiner closer to the plate, taught him how to study pitchers, and convinced him not to try to hit to the opposite field. Despite Greenberg’s efforts, Kiner’s season started slowly and manager Billy Herman wanted to send Kiner to the minors. Greenberg, however, intervened, convincing management to keep Kiner in the big leagues. Greenberg’s faith in his protégée was rewarded, as Kiner hit 51 home runs that year, with a batting average of .313.22

Branch Rickey became the general manager of the Pirates on November 6, 1950.23 Even though Kiner was still swatting home runs and drawing fans to the ballpark (although attendance decreased with the poor record of the Pirates), Rickey was not happy with Kiner’s high salary. Rickey wanted to trade Kiner and start anew with younger players. However, Rickey could not do this on his own authority. He needed the consent of John Galbreath, the president and an owner of the Pirates. Rickey began a multi-year smear campaign against Kiner with Galbreath. He also leaked false facts about Kiner to the press, hoping to diminish Kiner’s standing with the fans.24

On June 4, 1953, Branch Rickey got his wish, trading Kiner to the Chicago Cubs in a ten-player deal. Along with Ralph Kiner, the Pirates traded Joe Garagiola, Howie Pollet, and George Metkovich. The Pirates received Toby Atwell, Bob Schultz, Preston Ward, George Freese, Bob Addis, and Gene Hermanski, none of whom became anything special for the Pirates. Perhaps most important to Rickey, the Pirates also received a cash payment of $150,000. Since the Cubs were playing the Pirates that afternoon at Forbes Field, Kiner simply switched uniforms and played for the visitors in the game.

THE FENCE GOES UP

Turning back to 1947, just before the start of the baseball season and the arrival of Hank Greenberg in Pittsburgh, the Pirates announced major upgrades to Forbes Field. These included new bathrooms, dressing rooms, and dugouts, the reduction of the area behind home plate to the backstop fence, additional box seats, and the installation of Greenberg Gardens.25

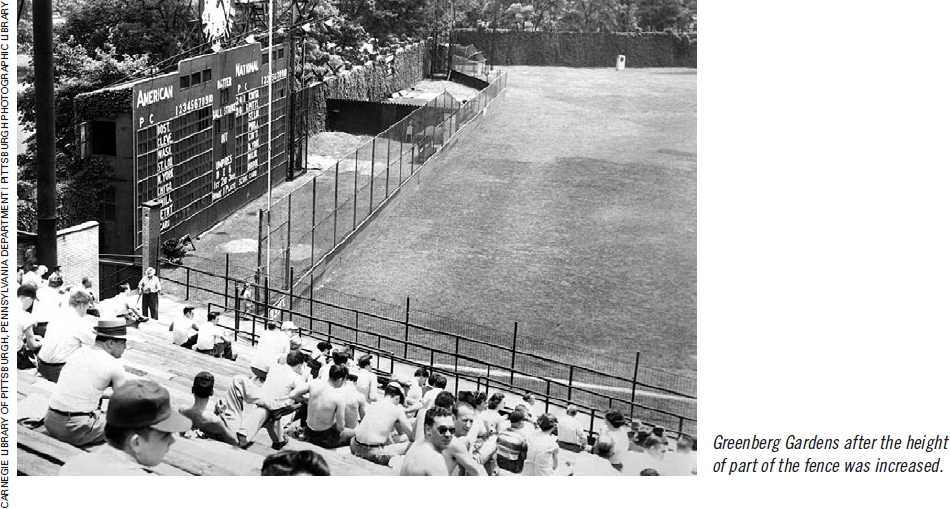

The Gardens was created by installing a fence that ran almost parallel to the left-field brick wall and scoreboard of the ballpark for about 200 feet, and then tapered at a sharp angle back to the outer wall, meeting that wall near the light standard closest to center field.26 This reduced the home-run distance down the left field line of Forbes Field by 30 feet and by slightly greater distances the farther away the fence was from the foul line. Previously, when a ball hit the scoreboard, it was in play and usually resulted in a double. Now a ball hit off the scoreboard—25.42 feet high on its sides and 27 feet in the middle—became an automatic home run.27

The Gardens’ fence was eight feet tall, with a three-foot high wooden base and five feet of fencing. Both bullpens were moved into the Gardens, with the Pirates’ on the left, the visitors’ on the right, and a wooden wall between them.

The Gardens was an aesthetic nightmare for one of the most beautiful ballparks in the major leagues. Because the original outer wall remained in place, the Gardens always looked like a temporary structure, never truly fitting in with the rest of the stadium. The fence cut out a chunk of the vast interior of Forbes Field, one of its significant attributes, with the outfield no longer seeming to be a never-ending expanse of green. The temporary fence distracted from the high and leafy trees of Schenley Park which surrounded left and center fields, and detracted from the red brick outer walls with their beginnings of hanging ivy.

Forbes Field was well known for the lack of advertising on its walls.28 But once Greenberg Gardens was constructed, a portion of the ivy in the middle of the visitors’ bullpen was removed and large white letters and numbers were placed on the wall there, announcing the Pirates’ next home game. A photograph of the era shows that on at least one occasion a banner was placed over the wall, advertising an upcoming promotion at Forbes Field. It is true that these were not third-party advertisements, as could be seen on the walls and scoreboards of numerous other major league ballparks of the era. These could properly be characterized more as announcements than advertising. Nevertheless, these announcements marred the character and beauty of the ballpark.

The debut of Greenberg Gardens on Opening Day at Forbes Field, April 18, 1947, was spectacular. The Pirates beat the Reds in a slugfest, 12–11. There were six home runs hit that day, five of which landed in the Gardens. Surprisingly, neither Hank Greenberg nor Ralph Kiner hit any, even though the Pirates hit five of the six. This unexpected outburst of homers, though, meant that Greenberg Gardens was mired in controversy right from the start. Harry Keck, the sports editor of the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, wrote, “The cheap home runs made a farce out of what might have been a pretty good ball game.”29

The controversy over Greenberg Gardens continued throughout the season (and, in fact, throughout its existence). On May 7, 1947, The Sporting News published an editorial decrying ball clubs which build fences in the outfield to benefit certain home-run hitters. The paper said, “The outstanding offense was the building of the so-called Greenberg Gardens in Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. … The Sporting News believes that in such matters as the construction of Greenberg Gardens, the issue of fair play is involved.”30

During the 1947 season, as Ralph Kiner took greater advantage of the Gardens than Hank Greenberg, some fans and writers started calling the area “Kiner’s Korner.” Once Hank Greenberg left, the new name became increasingly popular, but most people and writers continued to refer to the area as Greenberg Gardens, even after the Gardens’ demise.

Billy Meyer became the manager of the Pirates after the 1947 season. In December of that year, he visited Forbes Field for the first time in his career and got his first look at Greenberg Gardens. Meyer also looked at some of the statistics for the Gardens. He then intimated to the press that there could be changes made to the Gardens, including possibly tearing them out completely.31 Instead, the following year, the portion of the Gardens fence from the left field foul pole to a point near the visitors’ bullpen was raised to 16 feet, although it then quickly tapered down to eight feet, and then continued at eight feet for the rest of its length.32 This change may have had some success in reducing the number of Gardens home runs at Forbes Field. In 1947, 116 home runs were hit into the Gardens—in 1948, only 74.

After 1948, as disclosed in newspaper articles of the day, there were numerous discussions of demolishing Greenberg Gardens. However, the structure seemed to be impervious to criticism or the wrecking ball. The Gardens remained in place through seven baseball seasons and was finally removed before the start of the 1954 season.

WAS GREENBERG GARDENS A SUCCESS?

Greenberg Gardens was installed in Forbes Field with the initial intent of providing Hank Greenberg with the opportunity to hit more home runs in Pittsburgh. It remained in place after Greenberg left the team because Ralph Kiner was hitting lots of home runs into the Gardens, thereby drawing fans to the ballpark. Unfortunately for the Pirates, the visiting team also had the advantage of hitting at Forbes Field with a shortened fence. According to a 1954 article in The Sporting News, over its seven-year existence, visiting teams hit 285 homers into the Gardens while the Pirates hit only 265 such home runs.33 Given the Pirates’ woes as a team during the Gardens years, finishing in last place three times and finishing in the second division in every year except one, a 20-home-run deficit may not seem all that bad. Nevertheless, over the long term, Greenberg Gardens was a negative with regard to the Pirates’ fortunes on the field.

As to Hank Greenberg, the Gardens also cannot be considered a success. In his one year with the Pirates, 1947, Greenberg hit only 25 home runs. Of that total, 18 were hit at Forbes Field, of which nine landed in the Gardens. It is true that nine home runs were more than a third of Hank Greenberg’s home-run production that year, contributing to his landing in eighth place on the list of National League home run leaders for 1947. And without Greenberg Gardens, Greenberg’s home-run production in 1947 might have been truly abysmal. However, in addition to leading the American League in home runs in 1935, 1938, and 1940, Greenberg led the American League in home runs in his last season with Detroit, just before coming to Pittsburgh, hitting 44 home runs in 1946. A 25-home-run season in Pittsburgh must be considered a major disappointment for Hank Greenberg.

As to Ralph Kiner, however, Greenberg Gardens made his career. Of the 369 home runs that Kiner hit throughout his major league career, 71 landed in Greenberg Gardens.34 That is about 20% of his home run production. Without Greenberg Gardens, Kiner’s total career home runs would have been less than 300. Also, without the Gardens, instead of leading the National League in home runs for seven consecutive seasons, one of Kiner’s major claims to fame, Kiner would have led the League in only three of those seasons, 1946, 1949, and 1950. In 1948, he would have fallen to sixth place in the list of league leaders.35 Based on these statistics, it is clear that without Greenberg Gardens, Ralph Kiner would never have made it to the Hall of Fame.

Greenberg Gardens was therefore an incredible boon to Ralph Kiner’s playing career. Some people back then, and even to this day, contend that Ralph Kiner had an unfair advantage over other players because of the shortening of the left field home run distance at Forbes Field during his years with the Pirates.36 The facts are different.

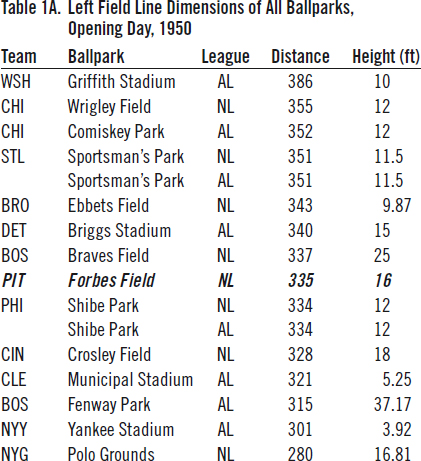

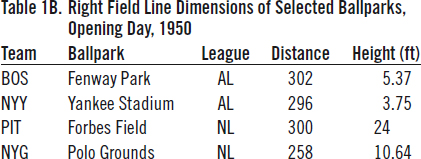

Table 1A contains a chart of the dimensions of the left field foul lines of all the major league ballparks as of Opening Day, 1950.37 As can be seen, about half of the major league ballparks that year had left-field foul lines that were shorter than Forbes Field’s, a few substantially shorter.

In fact, as shown in Table 1B, there were also some significantly shorter right-field foul lines in 1950, which would have helped home-run-hitting left-handed batters. In addition, the two replacement stadiums for Forbes Field had or have short left field lines. (See Table 1C.) The left field foul pole at Three Rivers Stadium was 335 feet from home plate for most of its existence, the same distance from home plate to Greenberg Gardens. At PNC Park, the distance down the left field line is 325 feet, ten feet shorter than the distance to Greenberg Gardens. Another relevant factor is the Major League Baseball rule which sets forth the minimum distances in the construction of baseball stadiums.38 It provides that for any baseball park built or remodeled after June 1, 1958, the distance from home plate to the foul poles must be at least 325 feet. Greenberg Gardens met that standard.

Thus, Ralph Kiner did not receive an unfair home-run-hitting advantage when Greenberg Gardens was installed at Forbes Field. It was a fair field of play that gave him the opportunity to become the greatest home-run hitter of his era. Kiner earned his selection to the Hall of Fame on his merits.

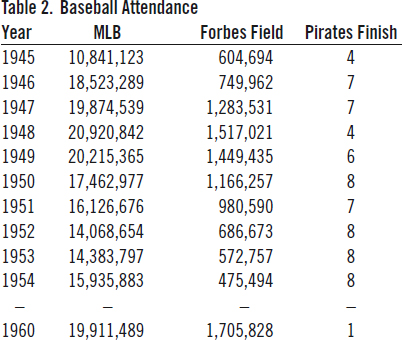

Of course, baseball is a business, even back in the 1940s and 50s, and the bottom line is what counts. Table 2 contains a chart of the total yearly attendance in major league baseball and the Pirates’ attendance at Forbes Field, from 1945 to 1954 and 1960.39 As expected, baseball attendance grew sharply at the end of World War II, as many important stars returned to the game from the military and the economy was strong. Between 1945 and 1946, attendance in the major leagues increased by more than 7.6 million fans or by approximately 71%. The Pirates’ attendance also increased between 1945 and 1946 but much more modestly.

However, the next year, 1947, with Greenberg Gardens in place, the Pirates’ attendance increased by more than 533,000 fans, or by approximately 71%. It continued to increase the following year, by another 233,000 fans (another 18%), while major league baseball’s total attendance increases were much more moderate in those years.

In 1947, for the first time in Pirates’ history, more than 1,000,000 fans attended the team’s games, a milestone that continued for the next three seasons, even though the Pirates were never close to winning the National League pennant in any of those years and, indeed, finished in the bottom half of the league in three of those four years. It was not until the World Championship year of 1960 that the Pirates were able to break their attendance record set in 1948. Of course, it is difficult to determine all the reasons for fluctuations in a baseball team’s annual attendance, but the addition of Hank Greenberg in 1947, and the home run hitting of Ralph Kiner in 1947 and subsequent seasons were significant factors.

Indeed, the title of a 1949 story in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette said it all: “Second-Division Pirates Draw Fans Because of Ralph Kiner.”40 According to the article, Pirates fans “had nothing but scorn for the impotent Pirates (who were 25.5 games out of first place), but they kept paying their way into Forbes Field to gaze, with the dewy-eyed reverence of Babylonian idol worshipers, upon big, amiable, good-looking Ralph McPherran Kiner.” In August 1950, the General Manager of the Pirates, Roy Hamey, said, in much simpler language, “Ralph is our gate. No player in the game is so important to his team.”41

Thus, the Pirates’ bottom line increased substantially through most of the Gardens years. Greenberg Gardens must therefore be considered a major financial success, even though it was not necessarily an athletic or aesthetic success.

THE FENCE COMES DOWN

Branch Rickey announced the trade of Ralph Kiner to the Chicago Cubs at a press conference around noon on Thursday, June 4, 1953. At a second press conference later that day, Rickey announced that the Gardens fence would be torn down before the Pirates’ game the following night with Cincinnati. Rickey said, “I don’t believe in building artificial barriers to suit any individual.”42 At that second press conference, someone whispered, “The guy wrecked the ball club at noon, now he’s wrecking the park.”43 At first, Warren Giles, the president of the National League, approved the removal of the Gardens.44

On the morning of June 5, 1953, the grounds crew at Forbes Field started to tear down the Gardens fence. A little after noon, however, Giles informed Branch Rickey that the fence could not be torn down during the season. It seemed that the National League had an internal rule to the effect that the dimensions of a ballpark could not be changed during a season without the approval of at least six of the eight owners. Three clubs voted against the change.45 The grounds crew then had to immediately reverse course and reinstall the portions of the fence that it had removed.46

Two of the teams who voted against the removal of Greenberg Gardens were the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Giants. Dodgers vice-president Buzzy Bavasi said, “We voted no on principle. It would be a bad precedent. According to what Rickey wants, a club could change its park to suit every trade it might make.”47 The name of the third team in opposition was not disclosed, but most people assumed it was the Chicago Cubs, who probably believed that since Ralph Kiner was going to play for them for the remainder of the year, they should let him take advantage of the Gardens as a visiting player.48 If that was the Cubs’ strategy, it did not work. Kiner played six games at Forbes Field as a Chicago Cub in 1953, with Greenberg Gardens in place, without hitting any home runs. (Nor did Kiner hit any home runs at Forbes Field the following year for the Cubs, with Greenberg Gardens gone.)

Greenberg Gardens was finally removed in February 1954.49 The bullpens were shifted back to their prior locations, with the Pirates’ pen down the right field line and the visitors’ down the left field line. Al Abrams, the sports editor for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, commenting on opening day at the ballpark that year, wrote, “‘Greenberg Gardens,’ the worst eyesore in Pittsburgh baseball history, was missing yesterday at Forbes Field for the first time since 1947.” Abrams further wrote that the capsule comment of the customers was: “Now, it looks like the beautiful park it used to be.”50

The removal of Greenberg Gardens after the 1953 season closed the book on its seven-year existence, allowing some statistical calculations to be made. During the existence of Greenberg Gardens, 1,041 home runs were hit at Forbes Field, of which 550 landed in the Gardens. That means that about 53% of all home runs hit at Forbes Field during that period were hit into Greenberg Gardens. Stated differently, there were more than twice as many home runs hit at Forbes Field from 1947 through 1953 with Greenberg Gardens in place than there would have been if Greenberg Gardens had not been built.

Of the 550 total home runs hit into the Gardens, Ralph Kiner hit 71 of them, or about 13%. Of the 265 homers the Pirates hit into the Gardens, Kiner hit about 27% of them. The most home runs Kiner hit in a season into the Gardens was 15 in 1948. Not counting his shortened season with the Pirates in 1953, the fewest home runs Kiner hit into the Gardens in a season was 7 in 1950, one of the years that Kiner would have led the National League in home runs even without the Gardens.

The most total home runs hit into the Gardens in a single season was 116 in 1947, the only season before a portion of the fence was raised from 8 feet to 16 feet. The smallest number of home runs hit into the Gardens in a single season was 58 in 1952. Wally Westlake, an outfielder and third baseman for the Pirates from 1947 to mid-season 1951, hit the second-most Pirate home runs into the Gardens. Out of his career total of 127 home runs, Westlake hit 37 into the Gardens.

The visiting team with the most home runs into the Gardens was the Brooklyn Dodgers, with 66; the fewest was by the St. Louis Cardinals, with 24. The visiting players with the most home runs into the Gardens were Jackie Robinson and Gil Hodges of the Brooklyn Dodgers, each with 13, and Bobby Thomson of the New York Giants, with 12.

AFTER THE GARDENS

Both Hank Greenberg and Ralph Kiner found success in baseball after their playing days. In 1948, Greenberg became the farm director for the Cleveland Indians, then in November 1949, the general manager. He put together the roster of the 1954 team, which set the American League record for most wins in a season (111), although they would lose the World Series in four straight to the New York Giants. In his eight years as Cleveland’s general manager, the team finished in first or second place six times. In 1956, Greenberg became the first Jewish ballplayer inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. The Tigers retired his uniform number (#5) in 1983. Hank Greenberg died on September 4, 1986.

Ralph Kiner remained with the Chicago Cubs for the remainder of the 1953 season and the entire 1954 season. He hit 35 home runs in 1953, but after that, his home-run production fell sharply. He was traded to Cleveland for the 1955 season, where he partnered once again with his buddy, Hank Greenberg. However, back problems caused Kiner to miss many games that season and he retired at the end of the year.

Kiner’s second baseball career was at least as successful as his first. In 1962, he joined the broadcast team of the expansion New York Mets. He said at the time that he was chosen “because I had a lot of experience with losing.”51 Kiner continued as a Mets broadcaster through 2013. He is still one of the longest tenured broadcasters with a single team in MLB history. In homage to Greenberg Gardens, Kiner’s post-game television show on WOR (Channel 9, New York) was called Kiner’s Korner and aired for over 30 years. Kiner was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1975; the Pirates retired his uniform number (#4) in 1987. Ralph Kiner died on February 6, 2014.

Forbes Field also had success after Greenberg Gardens was removed. Although it took a few years, the Pirates’ fortunes started to turn around in the late 1950s. In 1960, the Pirates won the World Series, beating the New York Yankees, four games to three. The two big blows for the Pirates in the deciding game were a three-run homer by catcher Hal Smith in the bottom of the eighth inning and the game-winning home run by Bill Mazeroski in the bottom of the ninth inning. Both were hit over the left field wall, with room to spare. On the greatest day in Forbes Field history, there was no need for Greenberg Gardens!

RON BACKER is an attorney from Pittsburgh who has written five books on film, his most recent being Baseball Goes to the Movies, published in 2017 by Applause Theatre & Cinema Books. He has also lectured on sports and the movies for Osher programs at local universities. Feedback is welcome at rbacker332@aol.com.

Notes

1. It was sometimes referred to as “Greenberg Garden” or “Greenberg’s Gardens,” but “Greenberg Gardens” is the most common appellation. Unless otherwise noted, the statistics in this article come from or were compiled from periodic charts published in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, under the title “Garden Homers,” reviews of game descriptions in the local Pittsburgh newspapers, Baseball Reference, and Retrosheet. Other sources may have slightly different statistics for home runs into Greenberg Gardens.

2. David Finoli and Tom Aikens, Images of America Forbes Field, Charleston, S.C., Arcadia Publishing, 2013, 16.

3. Robert Trumpbour, “Forbes Field and the Progressive Era,” in David Cicotello and Angelo J. Louisa, Forbes Field: Essays and Memories of the Pirates’ Historic Ballpark, 1909–1971, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2007, 26–27.

4. Sam Bernstein, “Barney Dreyfuss and the Legacy of Forbes Field, in Cicotello, 17.

5. “More Than 30,000 Persons Witness the Opening Game on Forbes Field,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, July 1, 1909, 8.

6. R.W. Lardner, “Nearly 36,000 See Cubs Bag Victory,” Chicago Tribune, July 1, 1909, 10.

7. Quoted in Finoli, 16.

8. Ronald M. Selter, “Inside the Park: Dimensions and Configurations of Forbes Field,” in Cicotello, 124–31; Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals (Fifth Edition), “Forbes Field,” Phoenix, AZ, Society for American Baseball Research, Inc., 2019. Lowry states that the original left field distance was 315 feet.

9. “Pirates From 24 States Prepare to Depart for Camp,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 8, 1925, 25.

10. Selter, in Cicotello, 131–34.

11. He played one game with the Tigers in 1930.

12. Scott Ferkovich, “Hank Greenberg,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/hank-greenberg.

13. The January 1, 1947, issue of The Sporting News included an error-riddled “scoop” that Greenberg wanted to play for the Yankees, including a photo of Greenberg holding a Yankees uniform, taken years earlier at a War Bond charity game, but passed off as current. “Briggs made no attempt to investigate—he had found the opportune moment to dump Hank and his inflated salary.” John Rosengran, Hank Greenberg: The Hero of Heroes, New York, NY: New American Library, 2013, 298.

14. Estimates of the price paid by the Pirates to the Tigers for Greenberg were between $40,000 and $85,000, according to Vince Johnson, “Greenberg’s Price Tag Is Reported ‘Around $50,000’,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 20, 1947, 14. Retrosheet states that the price was $75,000.

15. Rosengran, 302.

16. Harvey J. Boyle, “’Der Bingle’s’ Crooning Helped Persuade Hank,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 26, 1947, 16.

17. Rosengran, 303–04.

18. Rosengran, 310. According to Greenberg’s autobiography, the deal with the Pirates was always intended to be for just one year. However, at the end of the 1947 season, the Pirates asked him to come back for one more year. He declined, citing physical problems and his lack of interest in playing for a losing club. (Hank Greenberg, Ira Berkow, Hank Greenberg: The Story of My Life, New York, NY: Times Books, 1989, 176, 187.)

19. In three of those years, Kiner tied for the lead—in 1947 and ’48 with Johnny Mize of the New York Giants and in 1952 with Hank Sauer of the Chicago Cubs.

20. Robert P Broadwater, Ralph Kiner A Baseball Biography, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2016, 16.

21. Warren Corbett, “Ralph Kiner,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/ralph-kiner.

22. Rosengran, 306–07, Broadwater, 64–65.

23. John J. Burbridge, Jr., “Ralph Kiner & Branch Rickey: Not a Happy Marriage,” The National Pastime, 2018, 66.

24. Broadwater, 88, 100; Les Biederman, “$80,000.00 ’53 Pay For Kiner—5 Grand More If Sold, Traded,” and “Kiner ‘Hurt’ by B.R.’s Rap His Pay Demand Ridiculous,” both The Sporting News, March 25, 1953, 18.

25. Les Biederman, “Forbes Field Remodeling and Face-Lifting Cost $500,000,” Pittsburgh Press, March 30, 1947, 30.

26. Biederman, “Forbes Field Remodeling.”

27. Cicotello, 226.

28. On June 28, 1943, a 32-foot wooden Marine was erected to the right of the scoreboard at Forbes Field. Next to it was a promotional banner which said, “Buy War Bonds And Stamps.” It remained there through the end of the season. According to Cicotello, 226, this was the only advertising ever permitted on the outfield walls of Forbes Field. Other sources indicate that there was a war bonds banner installed during World War I. See, e.g., “The Ballparks: Forbes Field, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania,” https://thisgreatgame.com/ballparks-forbes-field.

29. Harry Keck, “Sports: Those Homers Too Much of a Good Thing,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, April 19, 1947, 11.

30. “Stop Tinkering With Ball Parks,” The Sporting News, May 7, 1947, 12. Other examples include the White Sox, in 1934, moving home plate at Comiskey Park out 14 feet toward the center field wall to aid its recent acquisition, Al Simmons, in hitting more home runs (“Sox Open ’34 Season With Detroit,” Chicago Tribune, April 17, 1934, 21, 23); the Washington Senators, in 1950, installing 854 new seats in left field and left-center field of Briggs Stadium, reducing the home run distances in those areas by 19 feet, to aid the right-handed home-run hitters in its lineup, such as Eddie Yost, Al Kozar, Al Evans, and Sam Mele (“Griff’s Shorter Left Field Will Stay If Nats Benefit,” The Sporting News, March 8, 1950, 14); and the Pirates, in 1975, moving the symmetrical wall of Three Rivers Stadium five feet closer to home plate, to aid its crop of home-run hitters including Willie Stargell, Al Oliver, and Dave Parker. (Bob Smizik, “Those New Fences…Home Runs or Heartaches,” Pittsburgh Press, April 6, 1975, 30, 33.)

31. Les Biederman, “Meyer, Rebuilder of Pittsburgh Team, Planning Changes in Ball Park Next,” The Sporting News, December 24, 1947, 6.

32. According to Les Biederman, “Homers To Come Higher at Greenberg Gardens,” The Sporting News, March 31, 1948, 6, the fence was raised to 16 feet. Other sources indicate that the height of the fence was raised to 14 feet. “Pirates Heighten Bull Pen Fence,” Pittsburgh Press, April 15, 1948, 36; Andy Dugo, “Tigers Here For Games,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, April 16, 1948, 28. In an April 1950 article about calculating home run distances at the Gardens, the Pittsburgh Press measured the height of the fence and found it to be 16 feet. Bob Drum, “Reporter Gets ‘Strung Up’ Seeking Accurate Answer,” Pittsburgh Press, April 2, 1950, 53. After the fence was torn down, The Sporting News wrote that the fence “was 16 feet in direct left and sloped to eight feet in left center.” “Greenberg Gardens Razed—Homers: Foes 285, Bucs 265,” The Sporting News, March 10, 1954, 29.

33. “Greenberg Gardens Razed—Homers: Foes 285, Bucs 265,” The Sporting News, March 10, 1954, 29.

34. “Gardens Gone But Memory Lingers On,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 13, 1954, 39.

35. This conclusion was reached after deleting the Gardens home runs of Kiner and those of his competitors in each season and then re-ordering the list.

36. For example, Dick Young, the New York sports writer, wrote at the time of Kiner’s selection into the Hall of Fame, on his 15th and final year on the ballot and only by one vote, “From the original Greenberg Garden grew the canard that Kiner was a cheapie home run hitter.” Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” New York Daily News, January 24, 1975, 41. Branch Rickey said of the Gardens, after he had it torn down, “The Gardens is only a cheap home run and who wants to see cheap home runs?” “Gardens Gone But Memory Lingers On,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 13, 1954, 39.

37. Oscar Ruhl, “Kiner’s Korner No Setup,” The Sporting News, March 1, 1950, 14; Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of All Major League and Negro League Ballparks (Fifth Ed.), Phoenix, AZ, The Society for American Baseball Research, 2019. Of course, the height of the fences or walls and the angle of the outfield fences from the foul lines toward center field are important factors in determining the likelihood of home runs in a particular stadium. However, based on the data available and the inconsistent locations of the measurements of ballpark distances, the length of the foul lines is a simple but effective way of comparing ballparks, and it is always an apples-to-apples comparison.

38. Rule 2.01, Note (a) and (b). The Commissioner has waived this Rule on several occasions. For example, the distance down the right field line of PNC Park is only 320 feet, but that is offset somewhat by the 21-foot-high Roberto Clemente fence in the area. “Close Call Sports,” June 19, 2012, https://www.closecallsports.com/2012/06/rule-104-note-minimum-fielddimensions.html.

39. Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/MLB/misc.shtml.

40. October 2, 1949, 22.

41. Al Stump, “What’s Ahead For Kiner?” 9 Baseball Digest, No. 8, August, 1950, 20.

42. “Greenberg Gardens to Be Torn Down,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 5, 1953, 1, 20.

43. Chester L. Smith, “The Village Smithy,” Pittsburgh Press, June 5, 1953, 37.

44. Lester J. Biederman, “Rickey’s Reputation At Stake in Kiner Deal,” Pittsburgh Press, June 5, 1937, 37.

45. Giles later called the vote selfish, unsound, and a means of seeking easy homers. “Giles Warns Baseball on Ballyhoo,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 11, 1953, 14.

46. Charles J. Doyle, “Greenberg Gardens Must Stay,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, June 5, 1953, 1.

47. “Giants and Dodgers (Plus 1) Prefer Gardens,” Pittsburgh Press, June 7, 1953, 63.

48. “Giants and Dodgers (Plus 1) Prefer Gardens.

49. “Greenberg Gardens Razed—Homers: Foes 285, Bucs 265,” The Sporting News, March 10, 1954, 29.

50. Al Abrams, “Sidelights on Sports,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 14, 1954, 18. At the same time, The Sporting News referred to Greenberg Gardens as “the atrocity in left field in Forbes Field.” Joe King, “Passing of Greenberg Gardens to Aid A.L.,” The Sporting News, April 14, 1954, 8.

51. Warren Corbett, “Ralph Kiner,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/b65aaec9.