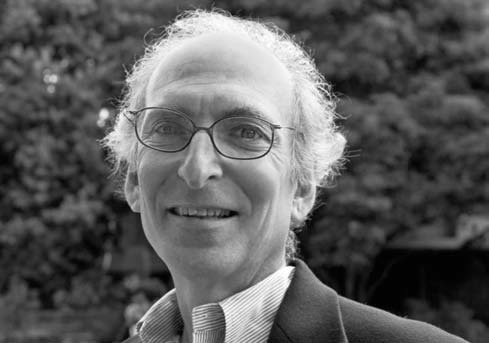

Henry Chadwick Award: Jules Tygiel

This article was written by Richard Zitrin

This article was published in Summer 2010 Baseball Research Journal

JULES TYGIEL (1949–2008) was born in Brooklyn, and part of him never left. His career as a historian began with his doctorate at UCLA, took him to Virginia and Tennessee, and ended with his untimely death from cancer in 2008 after thirty years at San Francisco State University.

Tygiel was best known for his 1983 classic on the evolution of baseball’s integration, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy. It received a Robert F. Kennedy book award, a place among Sports Illustrated’s greatest sports books, and the accolades of many who considered it the defining work on African Americans in organized baseball. His interviews with ex–Negro League stars were by themselves an important contribution, combining endless research, great empathy, and eloquent storytelling.

Tygiel wrote several other baseball books, including the rich and engrossing Past Time: Baseball as History, which received SABR’s Seymour Medal as the best baseball book of 2000. His other baseball contributions included monographs, book reviews, frequent appearances on television discussing Robinson and baseball’s integration, and a significant role in promoting the fiftieth-anniversary celebration of Robinson’s career. For twenty years, he co-taught, with his friend and colleague, Eric Solomon, a course at San Francisco State on baseball in history and literature.

Tygiel also was the cofounder (with me) of the West Coast’s first fantasy league, the Pacific Ghost League, which he served as commissioner. We were also partners in the first fantasy-league statistical service, Ghost League Baseball, which began business in 1985.

Jules grew up in East Flatbush. He was a product of Brooklyn public schools and Brooklyn College. He was, naturally, a Dodger fan, and saw his first game at Ebbets Field. While he spent most of his life on the West Coast, anyone who ever heard him speak knew, if only from his unmistakable accent, that they had not taken the Brooklyn out of the boy.

Among his “baseball buddies”—his fellow Ghost League “owners” and friends who joined him for Giants games or annual treks to watch Class A ball in California’s Central Valley—his opinions were not only respected but revered. His sense of humor was legendary. His fantasy team, the Tygiel Productos (named for the old five-cent cigar), produced piquant press releases and a team fight song, “Talkin’ Productos,” which he sang often and inevitably off-key, and always with a big grin.

Jules Tygiel was universally known as a gracious and giving teacher, father, husband, and friend. He was, despite his successes, down-to-earth and unassuming. While he had a healthy respect for his own opinions—he was completely comfortable in his own skin—he always maintained respect toward others and their perspectives.

He was also a man who loved his work. He ended the acknowledgments for his first and best-known book by describing his conversation with a young boy at a Mets game. When asked, Jules confirmed that he’d just been down on the field conducting interviews. The boy “looked at me, his eyes filled with admiration. ‘Boy,’ he exclaimed, ‘you are so lucky.’ The little boy in me smiled; he was so right.”