Honus Wagner’s Rookie Year, 1895

This article was written by A.D. Suehsdorf

This article was published in SABR 50 at 50

This article was originally published in SABR’s The National Pastime, Winter 1987 (Vol. 6, No. 1).

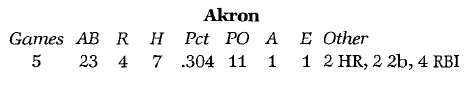

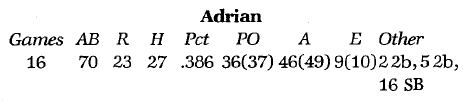

During the summer of 1895, John Peter Wagner — not yet known as “Honus” or “Hans,” nor yet as a shortstop — played at least 79 games for teams at Steubenville, Akron, and Mansfield, Ohio; Adrian, Michigan; and Warren, Pennsylvania. He rapped out at least 91 hits in 253 known at-bats for an overall average of .360.

The numbers are approximate, for reasons that will be explained, but they are a factual beginning to the hitherto unsubstantiated, or erroneously reported, record of Wagner’s first season in professional baseball.

Gaps in the great man’s stats have occurred through a variety of circumstances. His leagues — Inter-State, Michigan State, and Iron & Oil — adhered to the National Agreement. They were acknowledged in the annual Reach and Spalding guides and their organizational details were noted by Sporting Life, but by and large their statistics were ignored. Two of Wagner’s leagues and three of his teams collapsed while he was with them, leaving only random evidence of their existence. Contemporary newspapers, although the principal sources for this article, were erratic in their coverage and scoring.

Discrepancies in the available box scores raise the possibility that Wagner actually had 93 hits, which would improve his average to .368. There also were 11 games in which he made a total of 15 more hits, but in which, unhappily, at-bats were not scored. (His average at-bats in the games for which box scores are complete was 3.83; for those 11 games that would be, conceivably, 35. Add these to 253, and the 15 hits to 91 or 93, and you reach hypothetical averages of .368 and .375.) Finally, there were 12 games, including four exhibitions, in which Wagner probably played for which no boxes have so far been found.

Honus himself was a fount of misinformation when pressed for biographical detail many years after the event. In an early episode of a nearly interminable life story run by the Pittsburgh Gazette-Times in 1924, a boxed tabulation of the Wagner record carries a BA of .365 in 20 games at Steubenville and .369 in 65 games at Warren. Both, Honus claimed, were league-leading averages.

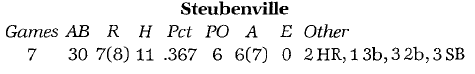

Actually, he played a mere seven games for Steubenville before the franchise was shifted to Akron, where he played five games more. He did hit .367 for Steubenville (or .400 if he deserves an extra hit one box score gave him) and .304 for Akron. Twelve games, however, are obviously too few for him to have been league batting champion.

If he hit .369 at Warren, it was not from 92 hits in 249 ABs in 65 games, as cited by the Gazette-Times. Wagner played his first game for Warren on July 11 and his last on September 11, a total of 63 days during which he missed 21 because of an injury to his throwing arm and several others because no ball was played on Sundays. In the playing days available to him, only 34 league games were scheduled (plus 19 exhibitions), hardly enough to support a claim to league batting honors. From the numbers I have at hand, I believe he played all 34 and batted about .324.

For all the uncertainty, a close look at Wagner’s rookie season gives us a fascinating look at a youngster developing in the minor leagues of 90 years ago. The enormous skills of his National League years – power hitting, exceptional range afield, base stealing ability – already were apparent. A reporter for the Mansfield Shield seems to have printed it first and said it best: “Oh! for nine men like Wagner.”

In 1895, John Wagner had just turned 21 and had been playing hometown ball around Mansfield, Pennsylvania. — now Carnegie — a coal-and-steel suburb of Pittsburgh, for some six or seven years. He was working in the barber shop of his brother Charley, presumably as an apprentice, but mostly sweeping up, running errands, brushing stray hairs off the customers’ suits, and trying to get loose to play ball.

He escaped the barber shop forever when George L. Moreland, owner and manager of the Steubenville club, wired him an offer of $35 a month. Moreland, who moved in Pittsburgh baseball circles, may have seen Honus as a kid, playing in the Allegheny County League, or he may have asked his third baseman, Al Wagner, Honus’s elder brother, if he knew any young prospects. Or maybe both.

At a Pittsburgh spring training camp in the mid-thirties, Moreland, by then a baseball statistician and historian, recalled Al saying: “I’ve got a brother who is a peach. He’s loafing now, and mebbe you could get him to play for you. If so, you won’t go wrong on him. He’s a great ballplayer.”

John tried to squeeze an extra $5 a month and got a wire back: “If you can’t accept thirty-five you had better stay home.”

Abashed, he jumped aboard a late-night freight hauling coal and was in Steubenville by 5 the following morning.

Wagner’s contract has several points of interest. First, he signed as “William” Wagner and thereafter became known as “Will” throughout the league. William was the name of still another ball-playing Wagner brother, and old Hans occasionally said he signed that way because he thought William was the Wagner Steubenville wanted. Well, perhaps, although that lets the air out of Al’s recommendation. On the other hand, Manager Moreland noted that the contract was received February 10, which was a mite early for third-baseman Wagner to be hanging around Steubenville offering advice on young prospects. Honus’s comment on the contract obviously was much later; maybe Moreland’s was, too.

The club obligates itself to pay expenses on the road, while charging the player for his uniform and shoes, a not-unusual practice in those days. Les Biederman’s 1950 biography of Wagner, The Flying Dutchman, has 76-year-old Honus recalling with amusement that $32 of his first month’s salary went for two uniforms and a pair of shoes.

Steubenville’s nine seems not to have had a nickname, but it had handsome “Yale gray suits,” with cap, belt and stockings of blue. On the left breast of the shirt was the letter S. A “decidedly pretty effect,” said the Steubenville Daily Herald.

Steubenville was one of seven Ohio teams in the Inter-State League. Wheeling, West Virginia, the eighth, justified the name. All the clubs were in a 275-by-80-mile area. Steubenville’s scheduled road games would have involved about 2,200 miles of travel.

Like many leagues of its time, the Inter-State began bravely, with well-attended games and intense local rivalries, then foundered amid turmoil and confusion, which led the acerbic reporter for the Shield to dub it the Interchangeable League.

“Will” Wagner appears in the Steubenville lineup for the first time on April 20, an exhibition victory over Holy Ghost College. He played right field, batted seventh, and went 2-for-5. (E. Vern Luse has backstopped my Steubenville, Akron, and Warren numbers by generously sharing his research into Inter-State and Iron & Oil League statistics.)

The regular Inter-State season opened at home on May 2 with a wild 29-11 win over Canton. Will was in left field, again batted seventh, and went 1-for-6, a homer in the fourth with a man aboard. He also got an outfield assist for nailing at the plate a runner trying to score from second on a single.

On May 4 he stole three bases against Canton, an individual effort not usually credited in game summaries, but available here because the paper published a play-by-play story.

On May 7, with the Kenton Babies in town, Will started in left and went 3-for-5, including a homer and a triple. He also struck out four in two shutout innings of relief — a short “row of post holes,” as scoreboard zeroes were sometimes called in 1895. Always a strong thrower, Wagner had done some impressive relief work in preseason exhibitions, and manager Moreland may have thought to make a hurler of him.

The following day, in a rain-shortened five-inning contest, Wagner pitched all the way. He gave up six runs and seven hits, including three home runs, but won easily as Steubenville teed off on Kenton pitching for 26 runs on 22 hits, two of them Wagner doubles.

Now considered a pitcher exclusively, Wagner sat out the next game and entered the one following in the sixth, with the Mansfield Kids already well ahead. He allowed two runs in two-plus innings.

Meanwhile, Moreland had telegraphed the league president, Howard H. Ziegler, requesting permission to transfer his club to Akron, pleading inadequate support by Steubenville. “Akron has the baseball fever in the most malignant form,” said the Ohio State Journal, “and has promised Moreland to receive his nine with open arms.” Belatedly, Steubenville began to raise money to keep the team in town and urged people in neighboring communities to come by streetcar and support the club.

President Ziegler, always mentioned scornfully by Mansfield’s Shield as a dilatory and do-nothing leader, acted promptly in this instance. He approved the move over the weekend and by Monday, May 13, the team represented Akron.

The first game in its new setting was a rousing 21–5 win over Findlay, whose location at the center of the state’s oil and gas producing region earned it the nickname “Oil Field Pirates.” Wagner, back in left field, had three RBIs with a homer and two doubles in six at-bats. “The Wagner brothers are little,” said the State Journal in a sidebar, “but the way they hit the ball is something awful.”

In fact, the more experienced Al was judged to be the more promising player. Batting cleanup in 13 games for Steubenville/Akron, he had 26 hits in 56 ABs for an overwhelming average of .464. He also scored 25 runs. Neither man, however, was physically small.

On the 17th, Will pitched a complete game at Canton’s Pastime Park, winning 14–7 and contributing three hits and a run. He allowed seven hits, including two doubles and a homer, walked four, hit two, and had a wild pitch. Not an artistic success. Even so, because of five Akron errors only one earned run was charged against him.

Akron’s final game was a 5–5 tie in the seventh when one of its players was called out attempting to steal third. A violent protest erupted, and when Moreland refused Canton’s request to remove an abusive player, the single umpire gave him five minutes to comply and then forfeited the game to Canton.

(Unaccountably, at-bats were not scored for this game. Since Wagner went hitless, and because of the rumpus probably did not bat in the seventh, I have arbitrarily given him three ABs.)

Following the game, Akron “went to pieces,” and its place in the league was awarded to Lima, OH, whose team, inevitably, was called the Beans. Canton immediately signed Al Wagner. Will was picked up by Mansfield. Claude Ritchey, the excellent shortstop, went to the Warren Wonders, where Honus would catch up with him again.

Honus was in the Mansfield lineup on May 20, batting second and listed as “J. Wagner.” Lacking a shortstop of Ritchey’s caliber, Mansfield’s manager, Frank O’Brien, gave the versatile Wagner his first try at the position.

He played through June 8, a total of 17 games for which box scores of 13 are available. The missing four involve games with the Twin Cities — Uhrichsville and Dennison, manufacturing towns adjoining each other on a bend of the Tuscarawas River — Cy Young country south of Canton. One game, at Mansfield on May 29, was skipped because the Shield did not publish on Memorial Day, and got only a paragraph in the issue of the 31st, which also had to report the holiday doubleheader. The other three — June 6, 7, and 8 at the Twin Cities, which meant the park at the fairgrounds, several blocks from beautiful downtown Uhrichsville — are forever lost. The Shield, like many small-town papers of the time, did not send a reporter on road trips, and there was no local coverage because the Uhrichsville Chronicle did not start publication in 1895 until after the baseball season: The summary under the line score for one of these three credits Wagner with a homer, so there is at least one AB, run, and RBI to add to his totals.

As it happened, Wagner did well when his team was thriving and tailed off when it slumped. While the Kids were winning five of the first six he played for them, his average was a fantastic .467. When they lost 10 of the next 11, he dwindled to .313. All told, he had a countable 24-four hits in a traceable 62 at-bats for a handsome .387 average. (It might even have been .403. In one game — again with the wretched Twins — the box gives him 1-for-5, but the summary credits him with a homer and a double. So, maybe he had 25 hits.)

In a 14-10 loss to Canton (and Brother Al), he had two home runs and three RBIs, then pitched relief in the sixth, evidently shutting down the Dueberites, as Canton was called, with one run in two innings plus. “Wagner Covered Himself with Glory,” said the Shield’s headline bank. And somewhat less kindly, for this could be a harshly critical paper: third baseman Jack Dunn “Loses His Head and His Stupid Playing Alone was sufficient [no cap] to Lose the Game.”

There is no indication of the distances to the outfield fences. One of Wagner’s homers was described as “a hot shot deep into center” and the other as an inside-the-park drive that the center fielder was slow getting to.

With the glove he did less well: 10 errors in eight games at short, one in two games in center, four in three games at third. This was called ‘’yellow’’ support in those days. The etymology is unknown, although it probably derives from the many pejorative uses of the word. Here it obviously means sloppy play that lets the side down.

Wagner was nothing if not willing. In one game at short he drifted into the center fielder’s territory for a fly and had to be called off. Another postgame note had the second baseman, Billy Otterson, a veteran who had played with the Brooklyn team in the old American Association, chewing him out for backing into the left fielder.

Against Canton on May24, he nearly put the Kids under all by himself. In the seventh, his “rotten fielding” allowed a batter to reach first. This so occupied the umpire’s attention that a Canton player, McGuirk — “McSquirt the robber,” the outraged Shield called him — “cut third base by at least twenty feet and the umpire allowed the score to count because ‘he didn’t see it.’”

The Kids went into the ninth leading 7-4 until two Wagnerian errors enabled Canton to tie it up.

“The agony of the rooters was painful, but it couldn’t be helped. Smith [Harry, a catcher who would be Honus’ teammate at Warren and for six years at Pittsburgh] was safe on Wagner’s [second] error and the rooters were ready to faint and were cussing Wagner in language which the pastors of Christian congregations do not use, but Smith was thrown out at second and the church members, who had been swearing like pirates, breathed easier.”

Mansfield rallied for nine runs in the 10th and won, 16–9. Wagner’s contribution was a walk.

With victory in hand, the Shield was more forgiving. “J. Wagner’s three errors yesterday,” it said, “were sheer awkwardness, but Wagner played a great all-around game and accepted chances outside of his territory which resulted in some of the errors marked against him.”

With 26 putouts, 43 assists, and 15 errors, Honus’ fielding average was a painful .821.

As May ended, the league’s perilous condition became obvious. Canton disbanded and Al Wagner and Harry Smith quickly jumped to Warren. The collapse put Mansfield in a bind. Well entrenched in last place with a record of 8-23, the club now faced an idle week through the loss of six scheduled games with the nonexistent Dueberites. The end came June 14. “LOCK THE GATES,” read the Shield’s one-column headline. “The Jig is Up with Mansfield for This Season.”

Al, looking out for little brother, wired John to join him at Warren. “Will come for sixty-five [dollars per month],” Honus wired back. “Send ticket.”

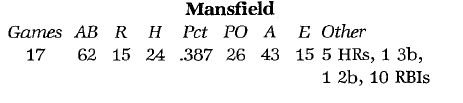

That was too steep for Warren, and Wagner moved on to the Adrian Demons of the Michigan State League — at $50 a month.

The long jump of an untraveled rube from Ohio to Michigan has a simple explanation. In 1949, Honus told Jim Long, then the Pirates’ PR man, that the Mansfield owner, “a man named Taylor,” said his brother ran a hardware store and a baseball team in Michigan and would have a spot for a hard-hitting youngster.

This time Wagner’s memory was on track. Mr. Taylor would have had to be William H., the father of Rolla L. Taylor of Adrian, who did, indeed, run a hardware store that was known throughout Lenawee County for its reliability. Moreover, Rolla was a prime mover in the consortium of Adrian businessmen who financed the Demons. He served as club secretary, managed the team, and selected as mascot his little son, Grandpa’s namesake.

William’s connection with baseball can be established only circumstantially today, but he was a member of a pioneer Ohio family, earned a captaincy in the Civil War, and between 1885 and 1895 was a partner in a Mansfield cracker factory which evidently was one of the regional bakeries amalgamated into the National Biscuit Company. He sounds distinguished and wealthy enough to have backed a small-town ball club.

Honus also told Long that, although he was a stripling with 29 games’ worth of professional experience, Adrian appointed him manager. Not so. Rolla ran the show.

The Michigan State League was a well-organized, well-run circuit of six clubs, located generally in the lower half of the State. Besides Adrian, which was also known as the Reformers, there were the Lansing Senators, Owosso Colts, Port Huron Marines, Battle Creek Adventists, and Kalamazoo Kazoos, Zooloos, or Celery Eaters, celery being a big local crop.

Adrian, the Maple City, performed at Lawrence Park and Wagner appeared in his first game there on June 20, playing second base and batting cleanup. In the first inning, the semi-weekly Michigan Messenger reported, Wagner “made the greatest slide for first probably ever made on the grounds, but in an effort to steal second his great slide failed to save him. He played on second base and did good work.”

It wasn’t all heroics, however. In his third game, he “took the stick with bases full and had an opportunity to distinguish himself, which he unfortunately did by striking out, and retiring the side.” He contributed a double and a triple later on, and Adrian beat Owosso in 10, 12-11.

Against Battle Creek the following day he came to bat with two on in the first and “almost lost the ball over between left and center fielders for a triple.” Not bad afield, either, according to the Daily Times: “Some of the ground stops he made were handsome plays in every respect.”

In a game against Port Huron, the best and worst of the young Wagner’s abilities were made evident. In the first he “made a beautiful stop” to retire the side with the bases full. In the third, again with bases full, a Marine drove the ball to right field, and a “wild throw of Wagner” — a relay, no doubt — allowed three Marines to score. Finally, in the eighth with three on, Port Huron “sent a red hot grounder to Wagner, who plays all over his field and half of the adjoining sections, [and who] made the best stop of the day and retired the side.”

All told, available stats give him 36 putouts, 46 assists, and 10 errors for .891.

For hitting, I am relying on Ray Nemec’s thoroughgoing research into the Michigan State League’s 1895 season, which he assembled some years ago. He credits Wagner with 27 hits in 70 ABs for .386. I have confirmed 14 of Wagner’s 16 games and am persuaded that the missing two would match Ray’s numbers.

An interesting aspect of Honus’ experience at Adrian was the presence of two excellent black players on the Demons’ roster, another piece of history authoritatively researched by Nemec. These were George H. Wilson, a 19-year-old righthander, and Vasco Graham, his catcher. Wilson appeared in 37 games — 30 complete — winning 29 and losing 4. He pitched 298 innings, allowed 289 hits and 173 runs. He struck out 280 and walked only 96. He hit .327 in 52 games as pitcher and occasional outfielder. Graham played in 67 and hit .324, with 19 doubles and 18 SB. I encountered one reference to them as Adrian’s “watermelon battery,” but the town’s, and the league’s, tolerance seems to have been exceptional and newspaper admiration of their talents genuine.

The Page Fence Giants (Bentley Historical Library)

The two were acquired from the Page Fence Giants, a highly successful team of black barnstormers organized by the legendary John W. “Bud” Fowler and sponsored by Adrian’s Page Woven Wire Fence Company. Fowler and many other players from the Page Fence Giants also played for the Demons, though not during Wagner’s few weeks. A measure of the Giants’ prowess can be gained from an account of an exhibition game between the Demons and the Giants 11 days before Wagner’s arrival. Watched by a crowd of 1,400, the Giants walloped the Demons, 20–10. Fowler, in right field, went 5 for 6. Sol White was at second base, got two hits, and took part in three double plays.

In later years, Honus laid his departure from Adrian to homesickness. There may have been more to it than that. During the exhibition with the Giants it was evident that some of the Demons were in a truculent mood. Referring to their haphazard play, the Messenger observed: “No club can play a good game unless harmony can prevail among them. When a set of men get to kicking about this and that, and seem dissatisfied, it is time they were called to a halt, and from all appearances the greater part of the team needed a calling down…. If Mr. [ J. T.] Derrick is manager of the club [he was not, but as pitcher and outfielder may have been field captain], the players under him should be made to obey….” Did this have something to do with the Demons’ reactions to getting shell-shocked by blacks?

In July, 12 days after Wagner’s departure, the Messenger reported: “Derrick was released this morning. There seems to have been a strong feeling among members of the club against him in some way, with the result that there was a greater or less lack [sic] of harmony in the organization. It is strongly hinted that Wagner left largely on account of that feeling.” What feeling? One could wish that the reporter wrote plainer, more felicitous English.

In a retrospective interview with manager Rolla Taylor in 1930, the Adrian Daily Telegram offered this paraphrase: “Wagner never ‘hitched’ so very well with the Adrian team. He didn’t like to play with Adrian’s colored battery. It was thought this had something to do with his quick departure.”

The trail ends there. Efforts to elaborate, or refute, the story through contemporary sources have been futile. I found no one in Adrian today aware of the history, let alone the personal circumstances. Perhaps it is less a comment on Honus than on the perniciousness and relentlessness of baseball’s color bar, which would soon be absolute and persist for more than half a century.

Joining Warren was like old home week for Honus. Five of his mates from the disbanded Steubenville club were in the lineup. Aside from Brother Al at third, there were Claude Ritchey at short; Dave “Toots” Barrett, a workhorse lefthander; Jakie Bullach (Bullock in Steubenville boxes), who could play second or the outfield; and outfielder-catcher Jimmy Cooper.

For all the talent, the Wonders were fifth in the Iron & Oil League, two games under .500, when Wagner arrived.

The I&O comprised six small cities in the northwestern corner of Pennsylvania, plus two refugees from the defunct Inter-State: the obscurantist Twin City Twins and Wheeling’s Mountaineers (or Stogies), whose factotum, also headed for the big leagues, was Edward G. Barrow. It had the usual dropouts and replacements, but seemed on the way to completing its split-season schedule.

Warren’s home field was Recreation Park, which the Pittsburg (no “h” in those days) Post called the finest in the league. In his first game there on July 11, Wagner had his one and only trial at first base. He batted fourth, following Al, and produced a double and a stolen base. The following day he was in right field and the day after that at short and batting second. He got four hits, including a home run, scored three, batted in three, and stole two bases. He had six assists afield and the Warren Evening Democrat told its readers: “John Wagner covers a great deal of ground at short.”

Of his first nine games, eight involved the same opponent representing two towns. Four were with Sharon (Pennsylvania), two of them played as exhibitions after the franchise folded and was transferred to the curious little town of Celoron (New York). Located, with its large neighbor, Jamestown, by Lake Chautauqua, Celoron was at the heart of the era’s famous “Chautauquas” — summertime tent meetings where huge crowds gathered for educational lectures, concerts, and revivalist sermons by evangelists. (A year later, a star attraction would be the ex-ballplayer, Bill Sunday.) Two of Warren’s four games with the no-nickname Celorons also were exhibitions as the league marked time before starting the split season’s second half. The ninth game, still another exhibition, was a loss at Warren, before a crowd of 1,000, to Connie Mack’s National League-leading Pittsburg Pirates.

As for Wagner’s performance, statistics are available for 17 games, half of those he played, including exhibitions. Several of the I&O League towns reported at-bats irregularly or not at all. This affects nine games in which he got 15 hits. For eight others, particularly those with Celoron, there is no coverage whatever. “The Jamestown people,” said the Warren Evening Democrat, “take a great deal more interest in balloon ascensions than they do in baseball.” This was an unseemly gripe, considering that the Democrat was among those that ignored at-bats.

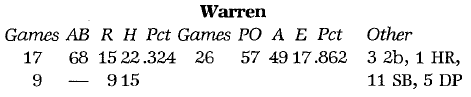

We know for sure that Honus went 22 for 68 in the 17 games, an average of .324. Fielding stats are complete for all 26 scored games: A not very impressive average of .862.

He played right field and third base, eventually taking over there from Al, who shifted to second. (“J. Wagner put up a good game at third … that seems to be a regular Wagner base.”)

Then, on Monday, July 29, the Democrat reported “while running to catch the train at Titusville, John Wagner fell and received a rather severe cut under his right arm. The muscles were not affected but it took several stitches to close up the wound…. It will probably necessitate his being out of the game for a week or so.” Actually, three. He rejoined the team for a game with the Franklin Braves and had a week of action before the league started to disintegrate. Three teams disbanded.

A 12-game winning streak in Wagner’s absence had moved the Wonders into the league lead, with the strong Wheeling organization some three games behind. When it was clear that the league could not continue, Warren agreed to play a seven-game series at Wheeling to decide the championship.

It was State Fair week at Wheeling, which guaranteed good crowds for the games, even though baseball was playing second fiddle to bike races and Buffalo Bill. One game was scheduled in the morning to avoid a conflict with Bill’s street parade of cowboys and Indians. Another was played at four in the afternoon, after the bike races.

Wheeling won four of the first six games, so that Warren’s victory in the seventh was technically an exhibition for another payday. Wheeling immediately claimed the championship. The Wonders, although hard pressed to ignore their agreement to a decisive series, could not help noting that their season’s record, including the seven at Wheeling, was 26 and 12 for .684, while the Stogies’ 27 and 16 was .630. Warren went on to lose two out of three to New Castle, languishing in third place, which thereupon had the temerity to proclaim itself the league champs. For what it’s worth, the A. G. Spalding Company, in its wisdom, sent a pennant to Wheeling.

Warren’s management wanted to keep the team going. It was only September 12, after all. But there was a small matter of paying the players, who had received nothing since the first of the month. A wrangling negotiation led nowhere and the players voted to go home. Last to leave were manager Bob Russell and the Wagner boys.

Whatever the statistical confusion of his season, John Peter Wagner was on his way. By August he was beginning to be known as “Hannes,” though not yet as a shortstop. Of the 67 games for which his position is known, only 10 were spent at short. He played 18 at third, 17 each at second and the outfield, one at first, and five on the mound.

If his fielding left something to be desired, it was not for lack of range or a strong throwing arm. And as a hitter, he already was awesome. He did not escape the notice of “Cousin Ed” Barrow, who would move on to Paterson (New Jersey) in 1896 and arrange to have Hannes with him.

Thereafter, it was Louisville, Pittsburgh, and the Hall of Fame.