How the Boston Braves Became the Bees

This article was written by Bob Brady

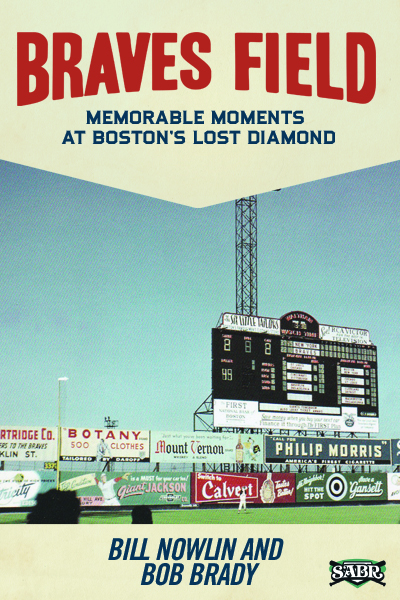

This article was published in Braves Field essays (2015)

Judge Emil Fuchs’ 12 seasons of stewardship over the Boston Braves concluded in 1935 after a valiant but futile last-gasp attempt to achieve solvency by luring an aged and ailing Babe Ruth back to Boston. At the direction of the National League, the team undertook a corporate reorganization at the end of the year. The Boston National League Baseball Company terminated its existence in favor of the newly organized Boston National Sports, Incorporated. Judge Fuchs’ principal financial backer, Charles F. Adams, was precluded from converting his substantial financial advances to the ballclub into a front-office position or even become an active shareholder in the new entity because Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis objected to Adams’s ownership of the Suffolk Downs horse racing track.

Judge Emil Fuchs’ 12 seasons of stewardship over the Boston Braves concluded in 1935 after a valiant but futile last-gasp attempt to achieve solvency by luring an aged and ailing Babe Ruth back to Boston. At the direction of the National League, the team undertook a corporate reorganization at the end of the year. The Boston National League Baseball Company terminated its existence in favor of the newly organized Boston National Sports, Incorporated. Judge Fuchs’ principal financial backer, Charles F. Adams, was precluded from converting his substantial financial advances to the ballclub into a front-office position or even become an active shareholder in the new entity because Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis objected to Adams’s ownership of the Suffolk Downs horse racing track.

At Adams’s behest, 66-year-old J.A. (James Aloysius) Robert “Bob” Quinn returned to the Hub from an executive post with the Brooklyn Dodgers to direct the destiny of the city’s National League entry. No stranger to Boston, Quinn had been the leader of a syndicate that bought the Red Sox from Harry Frazee in 1924 and operated the team until it sold out to Tom Yawkey in 1933. During his tenure, the cash-starved Quinn once considered selling Fenway Park and having the Red Sox become a tenant at Braves Field.

With a limited budget, Quinn’s challenge of restoring the Braves to a competitive footing in Boston with the neighboring Red Sox was made extremely difficult given Tom Yawkey’s willingness to deploy his vast wealth toward bettering the American League franchise seemingly regardless of cost.

Quinn decided to start from scratch and consigned the “Braves” nickname to the scrapheap, along with such associated epithets as Tribe, Wigwam, Tepee, Warriors, etc. He never cared for the name Braves, possibly because of its linkage to former owner James Gaffney and his association with New York’s Tammany Hall political machine. The team’s recent poor performance under that title further warranted a rebranding in his opinion to symbolically signal a new beginning. Seeking to stimulate some positive publicity, Quinn opted to solicit potential nicknames from the fans.

The proposed transformation met with only tepid resistance from a fan base that had rooted for the National League franchise as the Braves since 1912, when then new club president James E. Gaffney opted for a team characterization that reflected his ties to Tammany Hall. That political machine had derived its name from a Native American chief, Tamanend, of a clan within the Delaware Valley Lenni-Lenape Nation.

Senior circuit followers had become accustomed to periodic name changes dating back to the club’s charter membership in the National League in 1876. Starting out with nicknames linked to their apparel during the years 1876-82 (Red Stockings, Reds, or Red Caps), the team assumed a more local “flavor” when it was referred to as the Beaneaters from 1883-1906. Changes in ownership brought about the shorter-lived Doves (after the Dovey brothers, John and George; 1907-10) and Rustlers (after William H. Russell; 1911). Gaffney’s ascendency established an identity that was also reflected for the first time in team history as a logo on the players’ uniforms. An Indian in full headdress appeared on jersey sleeves and chests during his regime.

Quinn and company quickly launched a contest among club followers and the general public. A committee of regional sportswriters was charged with picking the winning replacement name. As an inducement, prizes would be awarded to lucky entrants who made the panel’s final cut. Quinn hoped for an outcome that would deliver a title associated with Boston or Massachusetts.

The contest exceeded expectations. The club’s office staff spent three weeks opening and sorting mail. Some 13,000 individuals throughout the United States expressed their preferences. Many sent in multiple choices, including one prolific entrant whose letter listed 73 potential candidates, none of which were ultimately chosen. Some 1,327 distinct monikers emerged from the mountain of correspondence. The pool of choices covered titles starting with every letter of the alphabet except “X.” Entries with a negative association to the disastrous past were quickly rejected (e.g., the Bankrupts, the Basements, etc.). As had been expected, hundreds offered Pilgrims, Beacons, Puritans, Minute Men, Sacred Cods, Bunker Hills, and other titles related to the history of the area. Also among the mix were such strange submissions as Aspirins, Comics, Pill Boxes, Hamburgers, Lemons, Zulus, and Zippers. Whittling down the list to a more manageable seven candidates, the jury of 25 sportswriters and one cartoonist deliberated for two hours in a room at the Copley Plaza Hotel. The group’s spokesman, senior journalist James “Uncle Jim” O’Leary of the Boston Globe, was charged with announcing the results. Receiving over half the ballots, the Bees led the pack with 14 votes. Following as also-rans were the Blue Birds (4 votes), Beacons (3 votes), and Colonials (2 votes). In the back of the pack, with only a solo vote each were the Bulldogs, Blues, and Bulls.

Allegations immediately arose that the newspapermen were motivated towards the winning submission because its brevity provided an ideal fit for headlines and that the title easily lent itself to wordplay and cartooning. In fact, it didn’t take long for the latter to commence. In announcing the name change, The Sporting News couldn’t resist the headline, “Boston Club Given Honey of a Name.” The publication extended its wishes that the newly christened team would experience a flow of honey at the turnstiles.1

In addition to his official designation of ballclub president, Bob Quinn soon became referred to as the King Bee and his manager, Bill McKechnie, as the Bee Keeper. Sports pages later would describe times when the Bees “swarmed” the field, “stung” their opponents and were “swatted” by adversaries. Famed scribe and club historian Harold Kaese summarized his feelings about the superficiality of this affair involving a perennial second-division ballclub by restating a well-known Shakespearean quote. “What’s in a name? That which we call a skunk cabbage by another name would smell as foul.”2

Thirteen fans had submitted the Bees nickname in the contest. A random drawing was conducted to award prizes. O’Leary drew the grand-prize winner’s name out of a hat. Arthur J. Rockwood, a sheet-metal worker from East Weymouth, Massachusetts, and the father of nine, received two season tickets for all Bees home games during the 1936 season. Eleven others were given pairs of tickets to the club’s home opener. To compensate the 13th fan, an out-of-towner from Chicago, a pair of passes to the first Bees-Cubs tilt of the season at Wrigley Field was sent his way.

When reporters expressed an intent to describe the former Wigwam as the Beehive, Quinn railed that they could call it whatever they wished but the ballpark would be formally titled National League Park.3

Reflecting Quinn’s preference, the entomological nickname was absent on tickets, programs and roster booklets. In its place appeared a bland “Boston National League” reference. However, Quinn’s edict seemed to soften as the years passed as the Boston Bees title found its way onto the cover of the 1938 spring-training roster booklet and a golden beehive and “Home of the Bees” slogan was placed on official stationery of the late 1930s.

Quinn was true to his word, with one minor alteration. The title of the ballpark, prominently displayed on the administration building above the field’s front entrances, received a new paint job. Gone was “Braves Field” and in its place appeared “National League Baseball Field,” and not “Park” as Quinn had earlier remarked. While the ballpark was referred to colloquially by some as “The Hive,” many stubbornly stuck to “Braves Field” when describing the Gaffney Street diamond. Following Quinn’s edict, the center entrance trolleys (a/k/a “cattle cars”) that delivered and picked up patrons at the ballpark replaced the Braves Field designation on the streetcars’ destination sign scrolls to now read “National League Park.”

Subtle changes occurred within the park’s confines. The Horace Partridge Company replaced the past use of “Braves” on its outfield wall advertisement to now read “Athletic Outfitters To The Bees.” Lifebuoy Soap followed suit and proclaimed that the Bees used their product to “stop ‘B.O.,’” which often drew the sarcastic retort that the team still stunk. Fans peering out into center field were urged to “Follow The Bees” on WAAB, a Boston radio station heading up a regional radio network from its studio at the nearby Hotel Buckminster in Kenmore Square.

The Boston Bees lasted until their “extermination” on April 29, 1941. On that date, the team’s ownership, influenced by the addition to its ranks of the “Three Little Steam Shovels” — Lou Perini, Guido Rugo, and Joseph Maney, voted to bring back the Braves designation and return the ballpark’s title to Braves Field, restoring the “Wigwam” nickname.

BOB BRADY joined SABR in 1991 and is the current president of the Boston Braves Historical Association. As the editor of the Association’s quarterly newsletter since 1992, he’s had the privilege of memorializing the passings of the “Greatest Generation” members of the Braves Family. He owns a small piece of the Norwich, Connecticut-based Connecticut Tigers of the New York-Penn League, a Class-A short-season affiliate of the Detroit Tigers. Bob has contributed biographies and supporting pieces to a number of SABR publications as well as occasionally lending a hand in the editing process.

Sources

A version of this story first appeared in Brady, Bob, The Bees of Boston: Baseball At The Hive 1936-1940 (Boston: Boston Braves Historical Association Press, 2012). That account was based upon contemporary local newspaper articles as well as from The Sporting News; Kaese, Harold, The Boston Braves (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1948), the Harry M. Stevens photographic archives, and the files of the Boston Braves Historical Association.

Notes

1 The Sporting News, February 6, 1936, 1.

2 Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves 1871-1953 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2004, first published 1948 by G.P. Putnam’s Sons), 235.

3 Bob Brady, The Bees of Boston: Baseball At The Hive 1936-1940 (Braintree: Boston Braves Historical Association Press, 2012), 2.