I Met Jackie Robinson’s First Major-League Manager

This article was written by Wayne Soini

This article was published in Jackie Robinson: Perspectives on 42 (2021)

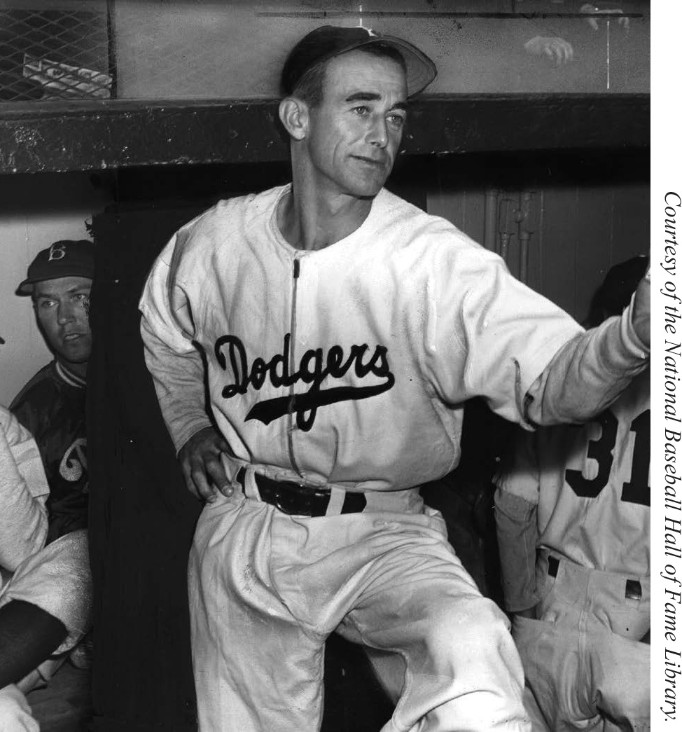

Clyde Sukeforth as Dodgers manager, 1947. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

I met Clyde Sukeforth three times altogether.

On the first occasion, Howard V. Doyle, an old Mainer, friend, and former boss who knew I’d be interested, invited me to join him on a trip to Waldoboro, Maine, specifically to meet Clyde, with whom he’d been on a first-name basis for decades. The story is that Howard had made part of his living from sports during the Depression. Also known back then as Dizzy Doyle, he formed a semipro basketball team to round a circuit of small towns in Maine. They played games against local teams for paid admissions, which were split differently depending on which team won; that guaranteed a hard-fought contest worth seeing. He was also good as a pitcher in semipro baseball. Such a man naturally found much in common with Clyde, a catcher with the Cincinnati Reds. They kept in touch after Howard moved to Massachusetts, where he had a long, even legendary career as a union leader, while Clyde worked for a succession of major-league teams when he was not hunting or fishing in Maine.

I met Clyde in about 1985 or ’86. Then as now, Waldoboro was a small town on Route 1, population about 5,000. When Howard stopped at a diner for directions, I noticed that the natives asked him questions before giving any answers. They were protective of their baseball hero’s privacy. Only after you passed the test as being somebody Clyde would likely welcome did you receive more than, “Yes, he lives here in Waldoboro somewhere, over down toward the shore.” Howard had the answers and the Maine accent to pass their tests.

(At the diner, I recall how we ate a quick meal, after which I selected one of the peanut-butter-frosted vanilla cupcakes under a glass case that just melted in your mouth. As we left, I asked for six of them in a box to go. There were only seven left.

(“I can’t sell you six, sir,” the hostess said. “Then, others would come here and be disappointed.” I settled for three in a stiff white bag to go.)

Clyde’s modest but neat and comfortably furnished home turned out to be located not very far from the diner. He welcomed us, quickly brought us inside, offered refreshments, and had us sit on a sofa in his spacious living room. On the wall was a framed Saturday Evening Post cover by Norman Rockwell.1 When we met, Clyde was in his mid-80s but still active and spry, a short and compact man, neither plump nor scrawny, of a sturdy build. He took a seat in an armchair beside us and chatted in succinct sentences and occasional dry humor.

By the way, it was not obvious to me that he was blind in one eye, although he had suffered such a devastating injury in a hunting accident in the 1930s. Clyde, who had batted .354 with the Reds in 1929 (84 hits in 84 games played), thereby lost most of his value as a player. (Only the manpower shortage at the end of World War II brought him back into play in earnest, over 18 games in the spring of 1945, during which he batted .294.)2 He had baseball value, however, as he had off-the-field talents that surfaced. It was as a scout and even (in two games) as manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers that Clyde had made his most lasting marks.

He talked about those days with us. First, Clyde said he thought that he was assigned to be a scout because of his years as a catcher.

“A catcher sees players closer up than anybody else. And we are not looking for the better points, we are looking for a batter’s weaknesses.”

Even with one good eye, his trained eye was of use to Branch Rickey.

“Jackie Robinson was just burning up the charts after the war,” Clyde said, a good degree of excitement still in his voice. As he described it, Branch Rickey sent him west to observe Robinson, then a star with the Kansas City Monarchs. Rickey instructed him to “pay particular attention to his arm” but, as Clyde summarized for us that day, not otherwise making his intentions explicit. Clyde said he saw a gifted player and after the game spoke with Jackie, telling him that he was there at Branch Rickey’s request and asking Jackie to come to Brooklyn.

“Why does he want to see me? Why is he interested?” Clyde said, reprising the emphatic and very persistent curiosity that Jackie showed, without Clyde’s being able to satisfy it.

Without more than that to say specifically, Clyde managed to get Jackie to agree to join him on a trip by train back to New York. (I think in fact this actually took a couple of efforts or talks, but Clyde did not address this point with us.) At some point, questions surfaced again and Clyde said Jackie said, “I have some questions.”

“I’m sure you do,” Clyde recalled saying (he smiled in reliving the moment), “and Mr. Rickey will have a lot of questions for you.”

This last remark suggested to me that Clyde had been better briefed by Branch Rickey than he let on to Robinson. However, by his account he maintained confidentiality about the topics of any future grilling in Brooklyn (as did take place). With this deflection of Jackie’s intense curiosity, Clyde had reached the climax and the end of his account. I think it was in that moment that Clyde experienced his greatest pride, persuading Jackie Robinson to trek to Brooklyn without revealing any more than he did – that “Mr. Rickey will have a lot of questions for” him. As soon as Clyde reached the door of the Montague Street meeting – of which he was the last living witness at this point – he stopped reminiscing and said, precisely, “And the rest you know.”

(Parenthetically, I do not remember whether Clyde promised me to write up a sketch of his role in the selection of Ralph Branca to pitch in what led to Bobby Thomson’s “shot heard round the world” home run of 1951. If not, then at home I promptly wrote him requesting such a note. Either way, Clyde obliged. He sent me a two-page handwritten note on small-sized stationery that explained what he did. I’ve given that to a nephew who collects baseball memorabilia, but I remember he commented in beginning the letter, “I hope this is the last time I have to give an account of this,” or some wording very close to that. He was sensitive about the event, not as to himself but in behalf of Ralph Branca, who he told us in his living room he thought had been unfairly criticized or maligned thereafter.)

A year or two later, Howard drove up to see Clyde again, one fine summer day, and I was gladly with him. I don’t recall if we were expected, or just dropped by. In any case, it was a short visit of a few minutes. We met outdoors, in Clyde’s front yard, and then walked around in back of his home, where his property limit was a tidal cove in which he kept an outboard motorboat.

During this meeting, I don’t think we discussed baseball at all. I remember Howard asking Clyde if neighbors complained, when he said that he usually rode out at high tides in the early morning, just at dawn, 5:30 or 6 A.M.

“I received no complaint,” Clyde said, standing at a sort of proud attention, “but I felt entitled to them.”

Howard told to me later that this passed as humor in Maine.

The final occasion I saw Clyde, he was well into his 90s. The local library of Waldoboro had arranged for a Clyde Sukeforth Day. When Howard and I arrived, Clyde was already seated in a sunny room surrounded by uniformed Boy Scouts and their leader, who interviewed Clyde on his career. Clyde mentioned having weighed finishing college (Georgetown University) or getting more into sports. His explanation was interesting. As he enjoyed athletic competition and liked the idea of time off during the hunting season that pursuing baseball would allow him, he became a player. When the leader quizzed Clyde about his brief manager stint – he replaced Leo Durocher at the beginning of the 1947 season, when that controversial Dodgers manager was suddenly suspended by Baseball Commissioner Happy Chandler – Clyde deflected celebrating his moment in the sun lightly with good humor.

With Clyde at the stern, the Dodgers won both games (against the Boston Braves) in Ebbets Field.

It is in the record books. His record was 1.000 as a manager, as the Scout leader put it.

“No manager has ever done better,” the leader said.

“None have done better,” Clyde agreed, while drily adding, “Some have done more, but none have done better.”

His heavy emphasis on the word “more” brought out the big laugh of the day.

In his living room and later in the library on his Day, Clyde chose to show a modest perspective. He had not only scouted Jackie Robinson. Historically, he took part in erasing baseball’s color line as a manager. Clyde was entitled to bring it out loud and clear but he didn’t. He left off each opportunity when I was present without boasting that on Opening Day of the 1947 season, April 15, 1947, as the acting manager of the Dodgers, he was the one who wrote “Jackie Robinson” into the batting order, making that game Jackie Robinson’s first game in the major leagues. Others have done more. But none have done better, indeed.

WAYNE SOINI co-authored Judge Fuchs and the Boston Braves, 1923-35 with Robert S. Fuchs, (McFarland & Co., 1998). He also contributed to the recent SABR book The Babe (SABR, 2019). Soini is a longtime member of and occasional speaker at meetings of the Boston Braves Historical Association. McFarland has accepted, for publication in 2021, Soini’s biography of Boston-born radio legend Norman Corwin, entitled Norman Corwin: His Early Life and Radio Career, 1910-1950. Soini, who holds a master’s degree in history from the University of Massachusetts Boston and a Juris Doctor from Suffolk University, recently retired after working over 30 years for labor unions.

Notes

1 Saturday Evening Post, April 23, 1949 cover. It is known by several titles, “Tough Call,” “Game Called on Account of Rain, Bottom of the Sixth Inning,” and “The Three Umpires.” The Brooklyn manager arguing in the background is plainly Clyde. Rockwell visited Ebbets Field during the 1948 season, along with a photographer. Clyde was not the manager in 1948 or 1949, but Rockwell was likely aware of Clyde’s history. If so, transparently, he wanted to memorialize as manager the man who had been the team’s temporary manager on the day Jackie Robinson began to play in the major leagues, Opening Day 1947. Rockwell used his artist’s license to elevate Clyde on a rainy day and perhaps, very subtly, to evoke baseball’s earlier moment in the sun.

2 In 486 major-league games over 10 seasons, Sukeforth hit for a .264 batting average (with a .319 on-base percentage). In the 399 games in which he caught, he committed 33 errors in 1,264 chances for a .974 fielding percentage.