‘I Will Catch the Bleeping Ball’: Roberto Clemente’s Defensive Skills

This article was written by Michael Marsh

This article was published in ¡Arriba! The Heroic Life of Roberto Clemente (2022)

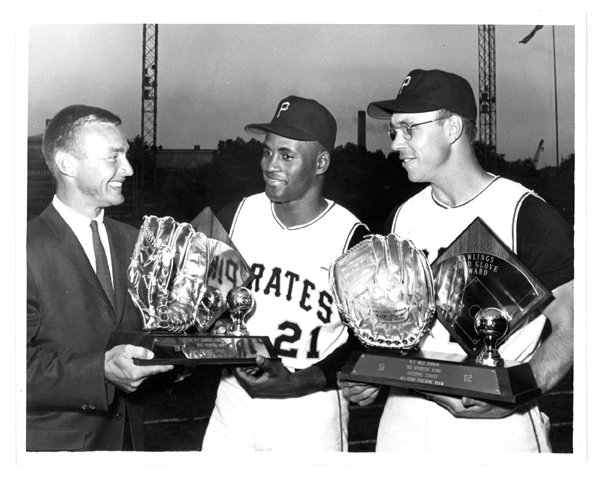

Roberto Clemente and Bill Virdon receiving Gold Gloves in 1962 from Rawlings employee Guy Palso. (Courtesy of The Clemente Museum.)

Roberto Clemente had gained many admirers of his defense as a right fielder for the Pittsburgh Pirates since his major-league debut in 1955. Clemente’s strong right arm and an array of running catches, basket catches, sliding catches, and leaping catches amazed fans, teammates, and rivals. During the twilight of his career, however, Clemente surprised even longtime observers with one of the greatest catches in major-league history.

On the night of June 15, 1971, Clemente patrolled right field at Houston’s Astrodome. Pirates pitcher Steve Blass held a 1-0 lead with one out in the bottom of the eighth inning. The Astros’ Joe Morgan, a fast runner, stood at first base. Houston’s Cesar Cedeno hit a line drive to short right field. Clemente slid and made the catch inches from the field to record the second out. Morgan stayed at first base.

The next batter, Bob Watson, nearly gave the Astros the lead. Watson drove a Blass pitch toward the right-field corner. Clemente knew the Astrodome had a unique rule: If the ball struck the wall above the home run line, Watson would get credit for a two-run home run.

Clemente bolted toward the wall. According to an article by Charley Feeney in The Sporting News, “Clemente, going full speed, raced toward the wall and, in one sudden move, makes a twisting leap for a one-handed grab, back to the plate, just before the ball would have hit above the yellow line on the wall, which is home run territory. When Clemente came down, his body hit the wall. He suffered a bruised left ankle and his left elbow also was swollen. Blood spilled from a gash on the left knee. Clemente slumped on both knees, back to the infield. The Houston fans stood up and cheered.”1

Astros manager Harry Walker had managed the Pirates between 1965 and 1967. Walker said Clemente’s catch was the best he had seen. “He never slowed up,” Walker said. “I don’t see how he could keep the ball in his glove.”2

The Pirates won 3-0. After the game, Clemente told reporters: “I don’t even think I could get the ball, but I had to try and I jump.”3

Clemente did more than try during his 18 seasons. He became part of a quartet of outstanding right fielders in Pirates history, along with Paul Waner, Kiki Cuyler, and Dave Parker, and he earned a place among the greatest right fielders in major-league history. He won 12 Gold Gloves, sharing the record for the most such awards by outfielders with Willie Mays. Among right fielders who have played in the major leagues since 1901, Clemente ranks second in putouts with 4,459 and second in assists with 255. He participated in 40 double plays as a right fielder.

Many runners tested Clemente’s arm and lost. Clemente record 266 assists as an outfielder. He led the National League in outfield assists five times. In 15 games, he recorded two outfield assists. He threw out runners at first base 22 times. Decades after Clemente’s death in 1972, an article in Inside Sports magazine rated his arm the best in baseball history.4

Clemente’s quest for fielding supremacy began in his hometown of Carolina, Puerto Rico.

According to Clemente biographer David Maraniss, Clemente’s mother, Luisa, passed on her strength to him. Maraniss wrote: “Luisa was a dignified woman, correct and literate, reading her Bible, always finely dressed, and not bulky, but she had muscular shoulders and arms with which she could lift the carcass of a freshly slaughtered cow from a wheelbarrow and butcher it into cuts of beef. (A powerful right arm was something she passed along to her youngest son. When people later asked about his awe-inspiring throws from right field, he would say, You should see my mother. At age eighty, she could still fling a baseball from the mound to home plate.)”5

Luisa Clemente recalled that her son began to prepare for a baseball career at an early age. “‘I can remember when he was five years old. He used to buy rubber balls every time he had a chance.’ Roberto constantly carried rubber balls in his hands; he squeezed them tightly, strengthening his hands and fingers. Roberto loved to bounce balls off the ceilings and walls of the family’s large, five-bedroom home.”6

During his preteen years, he befriended Monte Irvin. Irvin played outfield for the San Juan Senadores during winter baseball seasons on the island in the mid-1940s. Clemente admired Irvin’s batting style and throwing arm.7

Clemente further developed his skills during his teenage years. At 14, he played shortstop for a youth team. Clemente threw well, but the coach of the team thought Clemente was too slow for the infield and put him and his arm in the outfield. At Julio C. Vizarrondo High School, Clemente excelled in baseball and track and field. He especially liked the javelin. Clemente’s expertise in throwing the javelin aided him in playing baseball. “He may not have known it at the time, but the footwork, release, and general dynamics employed in throwing the javelin coincided with the skills needed to throw a baseball properly. The more that Clemente threw the javelin, the better and stronger his throwing from the outfield became.”8

Clemente’s efforts paid off in 1952, after he turned 17 years old. Clemente joined 71 other attendees at a tryout at the Santurce Cangrejeros’s stadium. Brooklyn Dodgers scout Al Campanis watched the hopefuls. Clemente made two strong throws, including one that flew nearly 400 feet.9 His batting and fielding impressed Campanis. The Dodgers eventually signed Clemente, who played for the team’s Montreal affiliate in 1954. Brooklyn lost him to the Pirates in a supplemental draft after the season.

During the following winter, Clemente played for Santurce in the Puerto Rico winter league. Herman Franks managed the team. Clemente played left field.10 Willie Mays played center. Bob Thurman played right field. Luis Olmo was a reserve outfielder. Clemente started using the basket catch during the season, encouraged by Franks and Olmo. “I miss fly ball many time ‘cause I try to catch too high,” Clemente told United Press reporter John Carroll a few years later. “It make it more easy for me to throw too, after I make the catch.” Mays had used the basket catch before Clemente, but Clemente denied that he imitated Mays.11

Clemente joined the Pirates in 1955. He paid dividends for the team quickly while on defense. On May 4 Pirates pitcher Bob Friend held a 5-3 lead over the visiting Milwaukee Braves with two outs in the ninth inning. The Braves’ Hank Aaron singled to right field, driving in a run and cutting the deficit to one run. Andy Pafko advanced to third. Clemente fielded the ball, but his wild throw allowed Aaron to move up to second. Next Friend pitched to George Crowe. Crowe blasted a ball to deep right field. Clemente jumped in front of the fence and caught the ball above it. He had taken a home run from Crowe to end the game.12

Clemente spent some time in center field, but Pirates manager Fred Haney made right field his primary position. Another Clemente biographer, Bruce Markusen, stated the reason: “Although Clemente played center field adequately, he seemed more comfortable in right. More importantly, his supreme throwing ability mandated a move to right field, a position that required a strong arm to deter runners from advancing too frequently from first to third base.”13

Markusen wrote that Clemente liked tracking balls in the spacious right field at Forbes Field and learned how to play caroms off the walls, which had wire screening and concrete that produced unpredictable bounces.14

Clemente employed three effective tactics in right field. He often picked up balls barehanded in order to execute a throw more quickly.15 He learned how to make sliding catches. Markusen wrote: “As Clemente slid with his legs extended, he grabbed the ball with his glove, and then almost immediately jumped to his feet and flung the ball toward the infield. By executing this genuinely athletic play, Clemente often prevented runners from stretching base hits into doubles or triples.”16 Finally, Clemente occasionally threw behind runners who had strayed too far after they rounded first base and thus recorded assists.17

Pittsburgh fans enjoyed Clemente’s play in the outfield. Markusen wrote: “With runners on base, any ball hit to right field became a source of anticipation for fans, who wondered if Clemente might unleash one of his patented powerful throws. Drives to the gap and bloopers to short right field often resulted in a furious chase by Clemente, who repeatedly ran out from underneath his poor-fitting cap. Even on routine plays, Clemente entertained fans with his delightfully unorthodox basket catch.”18

One fan, Henry Peter Gribbin, detailed his memories of Clemente. “Watching Clemente was indeed a treat for baseball fans,” Gribbin wrote, “when he was in Forbes Field’s right field, he developed his own special style of play, which was scrutinized by countless youngsters, including myself. After watching him, I had visions of making basket catches below the knees, of racing to the ball hit to right and then firing a strike to the first baseman, hoping to nail a runner who made too wide a turn.”19

Clemente expressed supreme confidence in his abilities. “I’m a better outfielder than anyone you can name,” he said. “I can go get a ball like Mays and I have a better arm.”20

During the 1960 regular season, Clemente had 19 assists. He had spectacular plays on successive nights. On August 4 the Pirates defeated the visiting Dodgers 4-1. Clemente played a ball off the right-field wall and threw John Roseboro out at second base to end the game. After the game, Pittsburgh Press sportswriter Les Biederman called Clemente better at playing the bounces than Waner. “With all due apologies to Paul Waner, who had first claim on the right-field wall, Roberto Clemente plays that sector better than any outfielder who ever went out there,” Biederman wrote.21

On the following day, Clemente made a catch similar to the one he would make in 1971 at the Astrodome. On August 5, 1960, the Pirates hosted the San Francisco Giants. Pirates pitcher Vinegar Bend Mizell held a 1-0 lead in the seventh inning. Mays stepped to the plate for the Giants and slammed a liner down the right-field line. “I must catch it.… I must catch it,” Clemente told himself.22 Clemente hit the right-center-field wall while he caught the ball. He fell to the ground with a bloody gash under his chin and knee bruises. The Pirates’ doctor closed the gash with five stitches.23 The Pirates won 1-0.

Danny Murtaugh, the Pirates manager, said it was the best catch he ever saw.24 The catch was included in the book Going, Going … Caught! Baseball’s Great Outfield Catches as Described by Those Who Saw Them, 1887-1964.25

Clemente’s defense helped the Pirates upset the New York Yankees in the World Series that year. After the Pirates took a 3-2 lead in the Series, a reporter for the Associated Press wrote that Clemente’s defense had boosted the Pirates. “Yet here was the player whose bullet throwing arm had stopped the Yankees from taking an extra base on hits to his territory, a feat that contributed mightily to Pittsburgh’s three victories.”26

Clemente notched another achievement in 1961. He won his first Gold Glove Award after he recorded a career-high 27 assists, 26 in right field. He supplanted Aaron, who had won the award the previous three years. That season, Aaron started 80 of 154 games in center field. Biederman wrote: “When Hank Aaron moved from right field to center for the Braves, Roberto Clemente moved front and center as the No. 1 right fielder. Clemente also has always felt miffed because Aaron was always voted the Rawlings Golden [sic] Glove as the best right fielder. Now he has full sway there.”27

A sample of Clemente’s fielding plays during the ensuing years demonstrate his prowess.

June 18, 1962: Cincinnati defeated host Pittsburgh 4-2. During the game, Clemente threw out Don Zimmer when the latter slid past second base.28

June 19, 1962: Cincinnati defeated host Pittsburgh 2-1. Clemente threw out Don Blasingame at first base when Blasingame tried to get back to the base after making a wide turn.29

August 27, 1965: Pittsburgh beat Houston 10-9 in 11 innings. As the Pirates’ infielders charged to the plate in the eighth inning, Houston’s Bob Lillis bunted near second base. Clemente, who had moved to shallow right field, ran into the infield, fielded the bunt and threw out Walt Bond at third base.30

September 6, 1965: Clemente helped Pittsburgh sweep Cincinnati 3-1 and 4-2. In the second game, he threw out Tony Perez trying to advance from first to third on Tommy Helms’s single in the sixth inning.31

September 1, 1966: Clemente threw out Jim Barbieri, who was running from third base, at home plate on a bases-loaded hit by Willie Davis in the top of the 10th inning. Los Angeles beat host Pittsburgh 4-3 in 10 innings.32

July 8, 1967: The Pirates defeated the visiting Reds 6-1. The Reds’ Lee May led off the top of the seventh inning with a triple off Tommie Sisk. After Sisk struck out Jim Coker, Jake Woods hit a pop fly to right field. Clemente pretended to prepare to catch the ball, freezing May at third base. Instead, Clemente let the ball fall in front of him, then threw out May at home plate.33

April 13, 1968: The visiting Pirates led San Francisco 2-0 in the bottom of the seventh inning at Candlestick Park. Clemente threw out Mays in the seventh inning as the latter tried to advance from first to third on Willie McCovey’s single. The Pirates eventually won 2-1.34

September 20, 1969: Pirates pitcher Bob Moose no-hit the host New York Mets 4-0. The Mets nearly broke up the no-hitter with two out in the sixth inning. Mets third baseman Wayne Garrett hit a fly to deep right field. Clemente went back to the fence and leaped to catch the ball.35

July 24, 1970: Pittsburgh beat Houston 11-0 during Roberto Clemente Night at the recently opened Three Rivers Stadium. Clemente dived to catch Joe Morgan’s line drive in the third inning and slid to catch Denis Menke’s fly ball in the seventh.36

Both Clemente’s opponents and teammates praised his defense.

Perez recounted Clemente’s 1965 throw against him years later. “I was on first base,” Perez said. “He was playing right field. I see he’s playing deep and [Tommy Helms] hit a bloop with one out. And I tried to get to third because he hit a bloop over the second baseman’s head. I say I think I’m not even watching the third base coach. I say I’ve got to make it to third and I turn around and I say it’s going to be easy. I’m running, I’m watching the third base coach Reggie Otero. Reggie said ‘Slide! Slide!’ I said, ‘Slide?’ I think you’re not supposed to slide.’ Before I slide, the guy got the ball and was waiting for me and I was out and I can’t believe it. How he threw me out when he was playing deep, the ball was hit soft and I look at Reggie like that [Perez looked up], like asking ‘How?’ and he said, ‘Come on kid, get out of here. It’s Roberto Clemente out there.’ I said ‘Oh man.’ I feel so bad about it. But it was great. I think that’s when I knew Robert Clemente had a great arm.”37

Ernie Banks compared Clemente to Willie Hoppe, the legendary carom billiards player: “Roberto, who plays a shallow right field, has been known to throw out batters at first base on drives hit on the ground. It’s practically impossible to go from first to third on singles into his territory. He plays those caroms off the slanting wall in right field like a Willie Hoppe. A runner on third is seldom sent home on a short fly to our friend.”38

Former Pirates pitcher Steve Blass said: “When Clemente was out in right field, there was nothing more a pitcher could want. I used to kid the guys by saying, ‘Bobby’s playing and there is peace in right field.’ I figured if the ball was hit to right and stayed in the ballpark, I had a chance. Some way, if it was humanly possible, and sometimes when it wasn’t, he would get there. If they had a rally going, I knew he might make an impossible catch and double off a runner and the rally would die. With him, it was like having four outfielders.”39

Two of Clemente’s longtime teammates, second baseman Bill Mazeroski and left fielder Willie Stargell, had watched him for 17 and 11 seasons respectively. They provided in-depth analysis about Clemente’s abilities.

Mazeroski said: “The fans may not realize it, but part of Clemente’s skill at running fly balls down comes from an unusual knowledge. Baseball is more of a mental game than it often is credited with being, and players like Clemente aren’t mechanical in their approach to it. For instance, he doesn’t just play the hitter, he plays the hitter with the pitch. The majority of outfielders go right to a spot thinking of something like: ‘Play this guy to pull just off the left side of the mound.’ And there they stay. But say there are two strikes on a hitter, Clemente knows he won’t be probably trying to pull as much, that he’s more apt to punch the ball; so he adjusts his position.”40

Stargell said: “First of all, he would make sure that he had good balance in throwing. Everything was [thrown] across the seams. And he knew how to throw the ball so that it could land in a certain spot and take one perfect hop to the infielder or the catcher so that it doesn’t handcuff him.” Stargell also mentioned a drill Clemente used to increase his accuracy. He placed a garbage can at third base. The opening faced him. Someone would hit a ball to him. Clemente fielded the ball and threw it into the can with one hop.41

Clemente’s annual assist totals declined from 1961. He never recorded as many as 20 again. Biederman defended him after the 1964 season. He wrote: “Roberto Clemente was charged with ten errors in right field but as one who saw Clemente in every inning, this correspondent believes Bobby is many times the victim of a scoring rule. Possibly half of Clemente’s ten errors came when his lightning throws from the outfield hit a runner as he slid into a base. Clemente, who often led the league in assists, only had 13 in 1964. The runners simply don’t take the chance on his fine arm anymore.”42

Later in his career, physical ailments affected Clemente. Among other issues, he suffered from a bad back, bone chips in his elbow, and shoulder soreness.43 He played only 108 games in 1970.

The following season, Clemente rebounded by playing in 132 games during the regular season. During the postseason, he helped spur the Pirates.

The Pirates upset the San Francisco Giants three games to one in the National League Championship series that season. Clemente’s defense helped preserve the Pirates’ 9-4 win in the second game. Pittsburgh led 4-2 in the sixth inning. San Francisco had loaded the bases. Mays batted with two outs. He hit a line drive that nearly fell between center field and right field. Clemente, who had moved to his right just before the blast, caught the ball to end the threat.44

Clemente also shined on defense while the Pirates beat the Baltimore Orioles in seven games to claim victory in the 1971 World Series. Clemente made two outstanding throws, one in Game Two and one in Game Six.

In Game Two, Clemente caught Frank Robinson’s fly ball near the right-field line, then spun and threw a strike to Richie Hebner at third base. Clemente nearly caught Merv Rettenmund, who had tagged from second base. The host Orioles won 11-3.

Clemente talked about his arm after the game. “Ask the other players,” he said. “They remember a few years ago when my arm was really strong. No one can compare with my arm when it feels right. I’m not bragging. That is a fact.”45

In Game Six, the teams were tied, 2-2, in the bottom of the ninth inning. The Orioles’ Mark Belanger stood at first base. Teammate Don Buford hit a ball that bounced off the right-field wall. Clemente fielded the ball at the warning track, turned clockwise, and threw to catcher Manny Sanguillen. The ball arrived with one bounce. Belanger held at third base. The throw helped preserve the tie, but the Orioles won 3-2 in 10 innings.

Despite Clemente’s fielding exploits, he had some problems. During his rookie season, he disliked playing in Ebbets Field and the Polo Grounds because he couldn’t figure out how the ball bounced off the walls at those fields.46 In 1959 Clemente made 13 errors in 104 games in right field and recorded only 10 assists. Maraniss explained, “Most of Clemente’s errors were on wild throws, often to third base. Some fans with seats in the third base boxes brought gloves to games with the specific hope of catching an errant heave from Roberto.”47 Clemente finished his career with a relatively low .973 fielding percentage and finished third all time with 131 errors in right field, in 2,433 games.

Yet, Clemente rose to the occasion throughout his career. His play on Watson’s June 1971 drive exemplified that quality.

After the game, Clemente discussed his catch with Nellie King, a former Pirates pitcher who broadcast the team’s games at the time. King recalled: “I’m sitting with him on the bus going back to the hotel, and I said, ‘Roberto, I’ve seen a lot of good catches, but that’s the greatest I’ve ever seen you make.’ And he said, ‘Nellie, I want to tell you something. If the ball is in the park and the game is on the line, I will catch the bleeping ball.’ That’s what he said.”48

MICHAEL MARSH is a freelance writer based in Chicago. A former staff writer for the Chicago Reader, he has also covered high-school sports for the Chicago Sun-Times and Chicago Tribune.

Sources

The author wishes to thank Bill Nowlin and the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the following books, periodicals, and websites:

Articles

“Runs Continue to Elude Astros,” Odessa (Texas) American, June 16, 1971: 18.

Biederman, Les. “Roberto’s Rifle Wing Amazes Fans, Shoots Down Cardinals,” The Sporting News, July 1, 1967: 15.

Hano, Arnold. “Roberto Clemente – Baseball’s Brightest Superstar,” Boys’ Life, March 1968, 24-25, 54; Vol. 58, No. 3.

Prato, Lou. “Why the Pirates Love the New Roberto Clemente,” Sport, August 1967: 34-37, 81-82.

https://pittsburghquarterly.com/articles/roberto-clemente-in-retrospect/.

Preston, J.G. “Dave Parker’s Remarkable 26 Assists in 1977 … and Roberto Clemente’s 27 in 1961,” https://prestonjg.wordpress.com/2015/08/08/dave-parkers-remarkable-26-assists-in-1977/.

Websites

https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Roberto_Clemente

Notes

1 Charley Feeney, “Greatest Catch? This One by Roberto Will Do,” The Sporting News, July 3, 1971: 7.

2 Bruce Markusen, Roberto Clemente: The Great One (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, Inc., 1998), 222.

3 Darrell Mack, “Roberto Draws Dome Cheers,” Cleveland News-Herald, June 16, 1971: 21.

4 Dennis Tuttle, “The Arms Race,” Inside Sports, August 1997: 30-37.

5 David Maraniss, Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), 20.

6 Markusen, 4.

7 Markusen, 5.

8 Markusen, 8.

9 Markusen, 9.

10 Markusen, 36.

11 John Carroll, “Clemente Credits Willie Mays’ ‘Basket Catch’ for ‘No Drops, Monongahela (Pennsylvania) Daily Republican, May 7, 1957: 2.

12 “Pirates Stun Milwaukee Braves, 5-4 To Cop 4th Straight Victory,” Somerset (Pennsylvania) Daily American, May 5, 1955: 7.

13 Markusen, 44

14 Markusen, 44.

15 Markusen, 77.

16 Markusen, 191.

17 Markusen, 77.

18 Markusen, 65.

19 Henry Peter Gribbin, “Watching Roberto Clemente Was Always a Consummate Treat,” Pittsburgh Senior News, July 28, 2016.

20 “Clemente Is Cassius Clay of Baseball,” Chicago Tribune, April 21, 1964.

21 Lester J. Biederman, “Hodges Lights Fuse, Dodgers Then Blow Top at Umpires,” Pittsburgh Press, August 5, 1960: 25.

22 Phil Musick, Who Was Roberto?: A Biography of Roberto Clemente, (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co., 1974), 147.

23 Lester J. Biederman, “Pirates Win ‘Finest Game,’” Pittsburgh Press, August 6, 1960: 6.

24 Maraniss, 95.

25 Jason Aronoff, Going, Going … Caught! Baseball’s Great Outfield Catches as Described by Those Who Saw Them, 1887-1964 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 235.

26 Maraniss, 123.

27 Les Biederman, “Corsairs Look to Patch Up Holes in Leaking Flagship,” The Sporting News, June 7, 1961: 13.

28 Les Biederman, “Brosnan’s 2 Books Sell,” Pittsburgh Press, June 20, 1962: 51.

29 Biederman, “Brosnan’s 2 Books Sell.”

30 Les Biederman, “Pirates Save Victory Streak with Six Run Rally in Ninth,” The Sporting News, September 11, 1965: 6; Markusen, 142.

31 Earl Lawson, “National League Race Tightens,” Cincinnati Post and Times-Star, September 7, 1965: 13.

32 “Pirates Miss Chance as Last Rally Fails,” Latrobe (Pennsylvania) Bulletin, September 2, 1966: 12.

33 Jim Ferguson, “Bucs Bounce Arrigo in 6-1 Waltz,” Dayton Daily News, July 9, 1967: 1D; Arnold Hano, “Roberto Clemente – Baseball’s Brightest Superstar,” Boys’ Life, March 1968: 24-25, 54.

34 “Pirates’ McBean Baffles Giants, 2-1,” Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Sunday News, April 14, 1968: 40.

35 Phil Pepe, “Moose 0-Hitter Mortifies Mets, 6-0,” New York Daily News, September 21, 1969: 112.

36 “Clemente Shines on His Night,” Pittsburgh Press, July 25, 1970: 6.

37 Tony Perez interview. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZkPf_ziVXwE.

38 Ernie Banks, “Clemente the Toughest in Banks’ Opinion,” Chicago Tribune, July 6, 1969: B1, B2.

39 Steve Blass, as told to Phil Musick, “A Teammate Remembers Roberto Clemente,” Sport, April 1973: 58, 90-92.

40 Bill Mazeroski, as told to Phil Musick, “My 16 Years with Roberto Clemente,” Sport, November 1971: 61, 63, 110, 111.

41 Markusen, 75-76.

42 Les Biederman, “Buccos Aren’t Bragging Over Their No. 1 Butterfinger Niche,” The Sporting News, November 14, 1964: 18.

43 Markusen, 255; C.R. Ways, “‘Nobody Does Anything Better Than Me in Baseball,’ Says Roberto Clemente,” New York Times, April 9, 1972: VI 39.

44 Bill Christine, “Robby Snaps Out of It Just in Time,” Pittsburgh Press, October 4, 1971: 38.

45 Maraniss, 248.

46 Les Biederman, “Clemente, Early Buc Ace, Says He’s Better in Summer,” The Sporting News, June 29, 1955: 26.

47 Maraniss, 90.

48 Markusen, 222.