If Gil Hodges Managed the Cubs and Leo Durocher the Mets in 1969, Whose “Miracle” Would it Have Been?

This article was written by Mort Zachter

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in Chicago (2015)

In 1969, the New York Mets became the first 1960s-era expansion team to win a World Series. En route to that championship, after overcoming a 9½ game mid-August Chicago Cubs lead, Gil Hodges managed his “Miracle Mets” to the National League East title over Leo Durocher’s Cubs. In Chicago, that season has been called the “Miracle Collapse.” 1

J.C. Martin, backup catcher for Hodges in 1968–69 and Durocher from 1970–72, inadvertently opened the door to revisionist history when he said, “Never once did I see Gil Hodges react in a way to cause panic. Never once! I don’t care what happened. We could pull the dumbest play in the world, but he’d never show panic. And he instilled that in his players…That was the big difference between the Mets and the Cubs. I found that out when I was traded to the Cubs just before the 1970 season. Leo was the type of manager to cause panic and confusion among his players…Gil would have won with the Cubs in ’69…the manager made the difference.” 2

Would the Cubs really have held on to win the Eastern Division had Hodges had been their manager? Analyzing their different managerial styles and how Hodges and Durocher utilized their rosters—especially in center field—shows that Martin may have a point.

One of the 1969 Cubs’ weak spots was in center field. Adolfo Phillips had filled the position from 1966–68. At first, Durocher had praised Phillips, a talented but sensitive player with power and speed. In 1967, his first full season in Chicago, Phillips played well, hitting 17 home runs and stealing 24 bases. His hitting, like that of many other players, slipped considerably in 1968, yet he was still an asset at a crucial position.

Phillips broke a bone in his right hand during spring training in 1969, however, and took more than a month to return. That was too long for Durocher, who publically embarrassed Phillips by saying, “He doesn’t want to play.” 3 By May, Durocher had benched Phillips and made rookie Don Young his starting center fielder. Young had batted .242 in Class A the previous season. 4

In June, Durocher deemed Phillips expendable and the Cubs traded him. At the time, the Cubs were 37–17; after the trade, they were 55–53. 5 From a managerial perspective, a key turning point of the season was Durocher’s knee-jerk reaction to Phillips’ slow return from injury. Contrast this with the support Hodges showed his center fielder, Tommie Agee.

In 1966, Agee clubbed 22 home runs, stole 44 bases, and won the American League Rookie of the Year award for the Chicago White Sox. But the following season he slumped and lost favor with his manager, Eddie Stanky. Hodges, an American League manager in 1966–67, had seen enough of Agee to know he was a gifted fielder. He felt he could handle Agee with a lighter touch than did Stanky, a disciple of Durocher who embarrassed Agee publicly.

“The first thing Hodges wanted to do when he became the manager was to acquire Tommie Agee,” Mets general manager Johnny Murphy said. “He wanted a guy to bat leadoff with speed [who] could hit for power. He also…needed a guy in center to run the ball down.” 6

On December 15, 1967, the Mets traded for the 25-year-old Agee. But in his first spring training at bat in March 1968, Bob Gibson beaned Agee with a high inside pitch. Gibson’s welcome-to-the-National-League pitch set the tone for Agee’s season; in the “Year of the Pitcher,” he hit .217 with only five home runs and 17 RBIs, striking out more than 100 times.

Hodges did everything he could to build Agee’s confidence. “He needs to relax a little,” Hodges told reporters, “He’s not alone. A number of other people around the league are in slumps, too.” 7 Years later, Mets outfielder Cleon Jones said, “Gil… took Tommie under his wing.” 8 While most players dreaded an invitation to the manager’s office, Agee felt comfortable enough with his new manager to discuss his personal problems. 9 And despite Hodges’ tendency to use his coaches as a buffer, he knew which of his players, like Agee, needed his support.

“Gil and Agee got very close,” Maury Allen wrote. “Agee would go into his office, close the door, and spill his guts with Gil…[who] was always willing to listen.” 10 In 1969, despite an average below .200 in early May, Agee finished the season at .271 with 26 home runs and 76 RBI and made two great catches in the crucial third game of the World Series.

In early July 1969, the Mets won five in a row on the road and returned home to play three games against the Cubs. Four days later, the Mets traveled to Chicago to play another three-game set. “There’s no question about it,” Hodges said, “the two series with the Cubs are bigger than any others….We need to take two out of three each time.” 11

They did, and the games revealed much about Durocher’s and Hodges’ differing approaches.

The first game, an afternoon tilt on July 8 before 55,000 fans at Shea Stadium, had World Series intensity and set the tone for the balance of the season. Jerry Koosman started against Ferguson Jenkins.

The Cubs led 3–1 in the bottom of the ninth, with Jenkins having had allowed just one hit. Ken Boswell hit a ball to shallow center field. Don Young misjudged the ball, which fell in for a double. With one out, Hodges sent Donn Clendenon up to pinch-hit. Clendenon hit a drive to deep left center. Young ran a long distance and caught the ball, but dropped it after crashing into the outfield wall. Cleon Jones then tied the game with a two-run double. After a walk and a groundout, Ed Kranepool came up with two outs and runners on second and third. Rather than pass the hitter purposely to set up a force play at any base, Durocher had Jenkins go at him. Kranepool poked a soft liner over the shortstop’s head, giving the Mets a shocking come-from-behind victory.

The Cubs lost the game and their composure, starting with their manager. In the Cubs locker room after the game, in front of his players and the press, Durocher laced into Young. “It’s tough to win when your center fielder can’t catch a fucking fly ball,” Durocher said. “Jenkins pitched his heart out. But when one man can’t catch a fly ball, it’s a disgrace. He stands there watching one, and then gives up on the other… My three-year-old could have caught those balls!” 12

The Cubs lost the game and their composure, starting with their manager. In the Cubs locker room after the game, in front of his players and the press, Durocher laced into Young. “It’s tough to win when your center fielder can’t catch a fucking fly ball,” Durocher said. “Jenkins pitched his heart out. But when one man can’t catch a fly ball, it’s a disgrace. He stands there watching one, and then gives up on the other… My three-year-old could have caught those balls!” 12

Adolfo Phillips might have caught them as well. Had Hodges managed the Cubs, would he have treated Phillips with encouragement and been rewarded, as he was with Agee’s breakout season? And if Durocher had managed Agee after his disastrous 1968 season, would Durocher have prematurely buried him as he did Phillips?

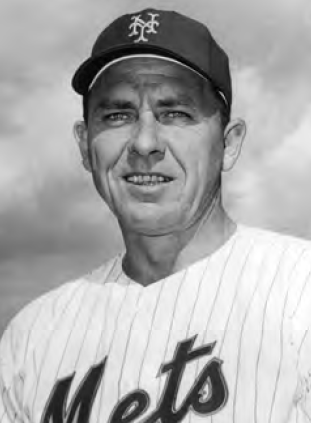

Mets center fielder Tommie Agee benefitted from Gil Hodges’ empathy and counsel.

Durocher came up short in other areas as well. On Saturday, July 26, during the third game of a weekend series at Wrigley Field against the Dodgers, Durocher complained he was ill and left the park before the game was over. The next day, Durocher, purportedly ill, failed even to show up. But Durocher was not sick. He had left the game early on Saturday to fly with his new wife on a chartered plane to Wisconsin for visiting day at his 12-year-old stepson’s sleep-away camp. 13 Durocher, caught off guard by the firestorm after he returned, blamed the local media—whom he consistently antagonized—for picking on him. Hodges was generally friendly with the media, especially veteran reporters like Arthur Daley and Dick Young, although the younger writers didn’t always appreciate him.

Despite taking days off for himself, Durocher insisted on playing his key regulars without rest throughout the hot Chicago summer at a time when every home game was played in the afternoon. “If a man had a slight injury or was just plain-tired, Leo didn’t want to hear about it,” Ferguson Jenkins said. “He just rubbed a man’s nose in the dirt and sent him back out there. You played until you dropped.” 14

That season, left fielder Billy Williams played 163 games; first baseman Ernie Banks 155; shortstop Don Kessinger 158; third baseman Ron Santo 160; and perhaps most shockingly, catcher Randy Hundley 151. 15 Most Cubs regulars slumped in September, when the Mets overtook them.

In contrast, Hodges platooned at first, second, third, and right. The only Mets to play 125 games that season were outfielders Tommie Agee and Cleon Jones. 16 This kept his infielders fresh for the stretch-run in September, when the Mets won ten straight games and the Cubs lost eight in a row. In addition, Hodges used his bullpen and five-man rotation to the fullest possible extent. No Mets pitcher threw more than 241 innings that season other than Tom Seaver (273 innings) 17 and nine pitchers won at least six games each. In contrast, two of the Cubs’ starting pitchers, Ferguson Jenkins and Bill Hands, each threw at least 300 innings 18 and only five Cubs pitchers won at least five games.

Had Hodges managed the Cubs, he probably would have used infielders Paul Popovich and Nate Oliver more often and not wasted a roster spot on Durocher’s personal favorite Gene Oliver, who spent most of the season on the active list but had just 29 plate appearances. Veteran pitcher Don Nottebart spent nearly all of 1969 with the Cubs and pitched only 18 innings. Nottebart later referred to the back end of Durocher’s bullpen as the “dead man brigade,” a concept that wouldn’t have existed on a Gil Hodges club.

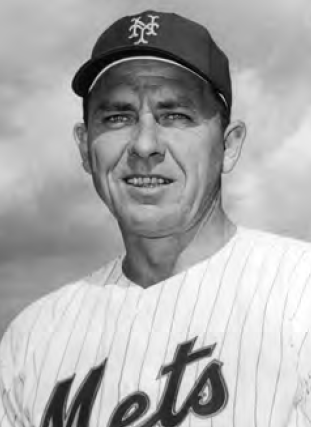

Talented but troubled Adolfo Phillips was one Cub that manager Leo Durocher had no idea how to motivate.

In his autobiography, Durocher wrote, “I never had a boss call me upstairs so that he could congratulate me for losing like a gentleman. ‘How you play the game’ is for college boys. When you’re playing for money, winning is the only thing that matters.” One way Durocher believed he would win was to have his pitchers throw at opposition batters, intending not just to back them off the plate but to hit them. But in a crucial Mets-Cubs game on September 8, 1969, Durocher was hoisted on his own petard.

That day, the Cubs—losers of four in a row and just 2½ ahead of the surging Mets—began a crucial two-game series at Shea. Jerry Koosman faced Bill Hands in the opener. Hoping to intimidate the Mets, Durocher ordered Hands to throw his first pitch of the game at Tommie Agee’s head. Agee hit the dirt, barely avoiding being knocked senseless. But Durocher’s strategy backfired. Koosman retaliated, hitting Cubs third baseman Ron Santo on the arm. Nobody on the Cubs bench moved.

In Agee’s next at-bat, he clubbed a two-run home run, and the Cubs were the ones who were backing away from the plate. Koosman struck out 13 for a 3–2 win. “Nobody told me to throw at Santo. Hodges didn’t say a word,” Koosman said. “It’s just something you learn. It’s how the game is played.” 19 The next day, Durocher pitched Ferguson Jenkins on short rest—he’d lasted just 2 1/3 innings three days before—and the Mets won, 7–1. Had Hodges been managing the Cubs, he never would have instructed Hands to throw at Agee. That was not how Hodges operated.

Despite spending most of their careers in the same city, Durocher and Hodges sang from very different hymnbooks. When he retired, Durocher had been thrown out of more games than any other manager except John McGraw. Hodges, in contrast, believed umpires were just men doing their jobs as best they could; showing them up accomplished nothing. And Hodges’ positive reputation proved crucial when he handed home-plate umpire Lou DiMuro a shoe-polish stained ball in Game Five of the 1969 World Series, claiming that Cleon Jones had been hit by a pitch. DiMuro reversed his call, awarding Jones first base in the turning point of the game.

Had Hodges managed the Cubs, and Durocher the Mets, that historic play would never have taken place. Chicago, instead, might have been doing the rejoicing.

A SABR member since 2006, MORT ZACHTER is the author of two books, “Dough: A Memoir” and “Gil Hodges: A Hall of Fame Life,” the second of which was published earlier this year by the University of Nebraska Press. He lives in Princeton, New Jersey and can be reached at mortzachter@gmail.com.

Notes

1 Doug Feldmann, Miracle Collapse: The 1969 Chicago Cubs (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006).

2 Stanley Cohen, A Magic Summer: The Amazing Story of the 1969 New York Mets (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2009), 246.

3 Glenn Stout, The Cubs: The Complete Story of Chicago Cubs Baseball (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2007), 270.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid. Phillips was batting only .224 at the time of the trade, but his on-base percentage was .424.

6 Richard Goldstein, “Tommy Agee, of Miracle Mets, Dies at 58,” New York Times, January 23, 2001.

7 Joseph Durso, “Mets Option Rohr and Keep Goossen,” New York Times, April 25, 1968.

8 Maury Allen, After the Miracle: The Amazin’ Mets Twenty Years Later, (New York: Franklin Watts, 1989), 186.

9 Maury Allen, telephone interview, December 19, 2006.

10 Allen, 188.

11 Joseph Durso, “Mets: Crossroads Ahead; Cubs Coming to Town,” New York Times, July 6, 1969.

12 Feldmann, 164. Generally, a more conservative manager, Hodges most likely would have walked Kranepool to create the force play at any base.

13 Rick Talley, The Cubs of ’69 (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1989), 78-79.

14 Ibid, 178.

15 Ibid, 336.

16 Cohen, 312.

17 Ibid.

18 Talley, 338.

19 Peter Golenbock, Amazin’: The Miraculous History of New York’s Most Beloved Baseball Team (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2002), 234.