In-Season Exhibition Games During World War II

This article was written by Walter LeConte

This article was published in Essays from Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II (2015)

When the United States entered World War II on December 7, 1941, one question among the many to be answered was: What will baseball’s place in American society be during wartime? Thanks to a letter written by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in January 1942, baseball’s role became clear. In that communication, known as the ”Green Light Letter,” the president, responding to an earlier handwritten letter by Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, encouraged the playing of baseball in spite of wartime circumstances.1 Roosevelt’s personal sentiments seemed to imply that regularly scheduled baseball games would give the country some semblance of normalcy and provide relaxation and entertainment to the populace, which affirmed its importance in the American way of life.2

When the commander-in-chief’s message became known to Americans, it enabled new baseball opportunities to present themselves. This was especially true with regard to scheduled in-season exhibition games (or ISEGs), not only between major-league nines but also between military teams and the big leaguers. These exhibitions carried an extra importance because service squads had many active-duty soldiers in baseball uniforms. Attendees would get the unique benefit of watching soldiers perform against major-league opposition.

In the United States during World War II, there was a dramatic rise in patriotism. Exhibitions played, especially military versus the pros, served an important role in demonstrating national solidarity. For example, fans were able to contribute to the war effort through such means as the purchase of war bonds. In this way, the heroism of thousands of veterans who defended the country overseas could be celebrated and supported. On numerous occasions, soldiers in large numbers were guests at these exhibition contests.

President Roosevelt seemed to be a catalyst for ISEGs to be scheduled. These games have been around since the origin of major-league baseball. In fact, pro teams have played in-season exhibitions against service clubs since 1918 and heroes, such as soldiers of World War I, were honored through such contests.

Prior to the Second World War there were few games played between major-league teams and military nines. The first such contests were played one year after the United States entered the First World War, on May 5, 1918. On that date, three ISEGs were played, one each by the Brooklyn Dodgers, the New York Giants, and the Philadelphia Athletics.3 The remainder of 1918 saw four additional exhibitions and the year ended with a total of seven. In the 1920s there were five games. One of those contests featured Babe Ruth. On September 3, 1922, the Sultan of Swat hit three consecutive home runs against the Third Corps Army Area team to lead the Yankees to a 12-3 victory. The game was played at Oriole Park in Baltimore, Ruth’s place of birth.4 There were nine in-season exhibitions with military teams in the 1930s. In the next decade, no ISEGs involving military teams occurred in 1940 and two in 1941.

With the emergence of the US involvement in World War II, there was an explosion of ISEGs, many involving active-duty military squads that challenged major leaguers and created a truly unique experience for baseball fans for at least four more years. The very first ISEG played in the World War II era between a military and a major-league squad during the championship season occurred on May 4, 1942, in Great Lakes, Illinois, home of the Bluejackets coached by Mickey Cochrane. The opponents were the Chicago Cubs. The pros took a two-run lead in the first frame then the gobs (nickname for sailors at that time) scored one in the bottom of the first and two in the second to take a 3-2 lead. The score remained the same until Chicago tallied two runs in the fifth, closing out the game with two more runs in the ninth for a 6-3 win. There was a scarcity of hits in the contest, each side with six. Only two players had two hits, one on each team. The contest was played before an audience of 8,000 sailors. The Cubs used 17 men, while Great Lakes used 10. There would be a total of 178 exhibitions played involving military teams and watched by tens of thousands, the last coming on August 27, 1945. That final exhibition occurred about one week before September 2, the official end of World War II.

During Cochrane’s 1942-44 tenure with the Bluejackets, he coached several major leaguers including Frank Baumholtz, Joe Grace, Johnny Lucadello, Benny McCoy, and Frankie Pytlak. His Bluejacket clubs were one of the most successful service clubs against the big leaguers.5 It was also the team that played the most games against the pros, with 31 ISEGs played and an overall record of 13 wins and 18 losses. The Mitchel Field Flyers on Long Island played the second most exhibitions, losing all 10 games of their games to the big leaguers.

From 1942 to 1945 there were many accounts of major leaguers who visited military hospitals and spent time with soldiers who were being treated there. In addition, there was usually an exhibition contest on tap for the enjoyment of the troops. On June 7, 1944, at the Valley Forge General Hospital in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, the Valley Forge Hospital club was pitted against the Philadelphia Athletics. The A’s pounded the hospital nine for 15 safeties, led by George Kell with three singles. The big leaguers won 10-2 and the three Philly hurlers allowed just two hits. A Philadelphia pitcher named Simmons, who never appeared in the majors, hit a homer. The Valley Forge team fielded 16 players, the A’s used 13 in the nine-inning ballgame. A crowd of about 1,000 were entertained.6

Major leaguers demonstrated support for American troops in a game at Framingham, Massachusetts, on August 28, 1944. The Boston Braves faced a team from the Army’s Cushing General Hospital and gained a 13-5 victory in the seven-inning contest. For the Braves, Buck Etchison led the way with four hits, among them a 400-foot triple. For the day, there were a total of 27 hits, 15 by the Braves. About 2,000 wounded veterans and fans witnessed the game.7

St. Albans Naval Hospital in Queens, New York, hosted a nine-inning contest on April 30, 1945. The Brooklyn Dodgers, who were not far from their home grounds, faced the team from St. Albans. The Brooklyn players visited with the men, toured the sick bay, and signed autographs. The site was called the Sherwood Oval and was about one mile from the hospital. The local Red Cross provided about 750 wounded soldiers a ride to the game and goodies like peanuts, popcorn, and soda were dispensed to the troops. The naval team, coached by Al Campanis, was tied going into the Dodger ninth when the Bums put up a two-spot to win the exhibition, 8-6, despite eight errors.8

Numerous ISEGs were featured players from different major-league teams that faced non-major-leaguers. A good example of this occurred at Yankee Stadium on July 28, 1943. After Cleveland whipped the Yankees in the first game, 11-6, the Chapel Hill (North Carolina) Navy Pre-Flight School nine, known as the Cloudbusters, played a combined squad of New York Yankees and Cleveland Indians, cleverly named the Yank-Lands. In the contest, witnessed by a crowd of 27,281, the Cloudbusters blasted the Yank-Lands by a score of 11-5. Among the 10 participants for the Cloudbusters, seven were major leaguers on active duty. They were Lt. Buddy Hassett (1B), Lt. Al Sabo (C), Ensign Joe Cusick (C), and Cadets Buddy Gremp (3B), Johnny Pesky (SS), Johnny Sain (P), and Ted Williams (RF). Sain tossed a complete game. The remaining Cloudbusters were Dusty Cooke (RF), Harry Craft (CF), and Ed Moriarty (2B). The Yank-Land club was managed by none other than Babe Ruth, who batted for pitcher, Ray Poat, in the sixth and was walked by Johnny Sain. Ruth hobbled on his injured ankle to second on a hit and was replaced by a pinch-runner, Tuck Stainback, who eventually scored.9

On August 26, 1943, at the Polo Grounds, Camp Cumberland of Pennsylvania, a military club, was defeated 5-2 by the War Bond All-Stars before 40,000 fans. In order to attend this nine-inning game, one had to wait in a line that was 10 blocks long to purchase War Bonds and thus gain a ticket. The All-Stars comprised members of the three New York teams, the Dodgers, Giants, and Yankees, and were managed by Leo “The Lip” Durocher. The Cumberland nine was managed by Major Hank Gowdy, the former Boston Brave who had been the first ballplayer to enlist in military service in World War I. Members of the All-Stars were selected by a War Bond League popularity vote. In all, 26 members of the All-Star squad participated and 17 players for Camp Cumberland appeared in the contest, with Captain Hank Greenberg among the members of this squad.10

Prior to this ISEG, a galaxy of All-Stars from the past, many in their vintage uniforms, took the field for a time, which permitted Walter Johnson a chance to pitch to Babe Ruth. After he fouled off some pitches, The Babe obliged the fans by hitting a home run into the upper right-field stands. Connie Mack managed the All-Stars. The infield was George Sisler at first, Eddie Collins at second, Honus Wagner at short, and Frankie Frisch at third. The outfield was Duffy Lewis in left, Tris Speaker in center, and Red Murray in right. Roger Bresnahan was the catcher and Bill Klem, the 37-year National League umpire, took his place behind the plate. It is uncertain how many frames this old-timer’s event lasted and it seemed to be arranged just to have Walter Johnson pitch to the Babe, who knocked one out.

A most interesting ISEG was played on June 26, 1944, in which the three New York clubs faced each other in the same game on a Monday night at the Polo Grounds in Manhattan. No military teams were involved but the admission charge went to the war effort. A crowd estimated at 50,000 was there not only to see a unique contest but also, more importantly, to contribute to a War Bonds drive. War Bonds were issued by the United States government as debt securities to finance the war effort. Posters advertising these bonds could be found nationwide in an emotional appeal for citizens to purchase them as a sign of patriotism.11 Bleacher seats were a pricey $25, reserved seats were $100, and box seats were $1,000. The income from the admissions alone was $5,500,000– a phenomenal amount for that time.12 The contest was the brainchild of Stanley Oshan of the War Finance Committee.

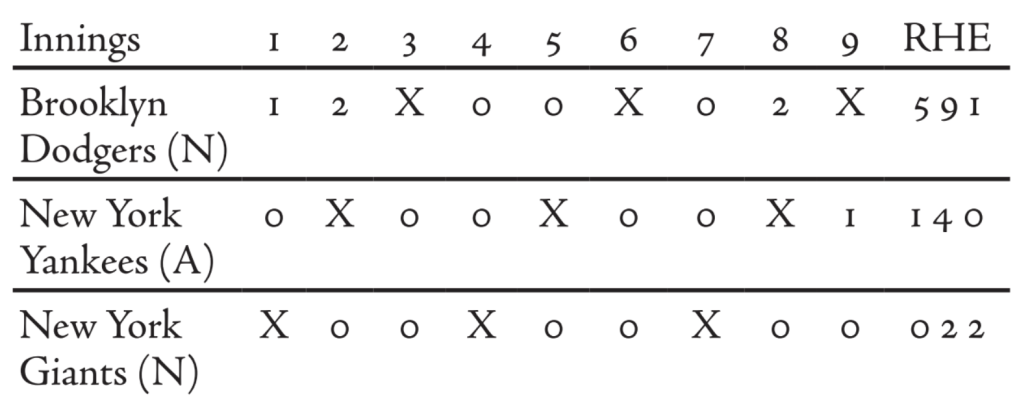

To determine the logistics of how three teams could play each other in the same game, a mathematics professor at Columbia University, Paul A. Smith, used a slide rule to “chart” the exhibition. Each of the three clubs,,the Dodgers, the Yankees, and the Giants, engaged in a game which was defined several ways: three-cornered, tri-cornered, triangular, three-way, and three-dimensional. Whatever it may be called, it certainly was one for the ages. Each of the three teams fielded and batted six times (see line score) with the Dodgers finishing on top with five runs. There were no home runs and no pitcher win or loss was awarded. Of the 15 total hits, two were doubles and one a triple. A total of 39 players participated in this wild contest and none had more than one hit or one run. In the second frame, the Dodgers took a 3-0 lead that they never relinquished. This unique affair took just 2 hours and 5 minutes even with all of the movement of the players to and from the field. This game time is truly amazing. It was broadcast live in New York on WINS radio –unfortunately the audio of the broadcast did not survive.13

The line score:

On July 20, 1943, the Yankees overwhelmed the Mitchel Field team of Long Island, New York, by a count of 31-6 for the most runs ever in an ISEG by major leaguers versus a military club. The Bronx Bombers lived up to their name with 66 total bases, on 14 singles, five doubles, six triples, and six home runs. New York’s Roy Weatherly hit for the cycle. Joe McCarthy’s nine also posted 31 hits and a 12-run eighth inning. This contest, in which 37 runs were tallied, was completed in 2 hours and 17 minutes, with a run scoring about every three minutes and 45 seconds. Mitchel Field scored four runs in the bottom of the ninth.14

Only once has a military nine scored 20-plus runs against a big-league foe in an ISEG. This occurred on June 5, 1944, when the undefeated Sampson Naval Training Center whipped the Boston Red Sox, 20-7. This was Sampson’s first encounter with major leaguers that season; the Sampson team was on a nine-game winning skein. The naval team racked up 25 hits and scored 10 runs in the eighth, the final inning of the contest as the Red Sox had to catch a train. Johnny Vander Meer started for the Sampson club.15

In 1944 four pro teams (the Cleveland Indians, New York Giants, Boston Red Sox, and Boston Braves) each played two ISEGs on the same day versus two different service nines! The common opponents for each of the four big-league clubs were Camp Thomas and Camp Endicott, both Seabee bases. All games were played on adjacent fields at Davisville, Rhode Island, the site of the Naval Construction Battalion and home to the Navy’s Seabees.16

On May 9 the Indians defeated Camp Thomas in the first game, 7-1. In the second game, Camp Endicott was held scoreless by Cleveland, which scored but one run.17 On June 16 the Giants beat both Camp Thomas and Camp Endicott by the scores of 7-3 and 4-1.18 Then the Red Sox paid a visit to both Seabee bases on June 27, coming out on top twice, 3-1 and 5-2.19 The last of these contests was played on July 12. On that date, the Boston Braves beat the Camp Thomas club in the first game, 7-1. In the second game versus Camp Endicott, Braves hurler Ben Cardoni tossed a three-hit shutout, 1-0.20 Seven of the eight contests were seven-inning affairs; the final was eight frames. The bigs went on to sweep the military clubs, eight games to none.

The very last ISEG between a service squad and major leaguers in the World War II era occurred at New London, Connecticut, on August 27, 1945 (about a week before the official end of the Second World War). The exhibition pitted the host Coast Guard Bears against the Boston Red Sox. The Red Sox won the nine-inning contest, 12-8, pounding out 16 safeties. The hero was Boston pitcher Emmett “Pinky” O’Neill, who tossed a complete game and blasted a pair of two-run homers off Coast Guard hurler Bob Thompson. The Red Sox hit the Bears with a five-spot in the fourth frame and two three-run innings in the sixth and seventh frames, sending Thompson to the showers. Red Sox pitcher O’Neill played in his last of three seasons with the Red Sox in 1945.21 The Red Sox concluded the 1942-1945 wartime ISEG era with 21 such games, the most of any major-league club, with a record of 15-6, a .714 winning clip. The Philadelphia Athletics had 18 victories, followed by the Boston Braves and Chicago Cubs with 17 apiece. The Detroit Tigers played the fewest exhibitions, four, followed by the Pittsburgh Pirates with five appearances. Each of the 16 big-league clubs of that time played at least one ISEG versus armed-forces nines.

The pros played and defeated tough service teams of all branches along the way, teams with nicknames such as the Bluejackets, Plainsmen, Eagles, Flyers, All-Stars, Bombers, Comets, Wings, Cadets, Commodores, Seabees, Leathernecks, and Cloudbusters. Many of the team names incorporated military terms such as barracks, ordnance, Quonset, signal corps, cadets, battalion, air base, and sub base.

During the World War II years, ISEGs became an integral part of baseball. A grand total of 326 in-season games were played from 1942 through 1945, an average 81 per year. Of the 326, a total of 178 or about 55 percent were played between major leaguers and military clubs. There were 20 ISEGs played in 1942; 68 in 1943; 54 in 1944; and 36 in 1945. That total includes four games with combined major-league squads. Those four exhibitions with combined teams involved the Yankees/Indians; Dodgers, Yankees and Giants; White Sox and Senators; and Braves and Reds. The final mark for the pros was 124 wins, 50 losses, and 4 ties. That’s a winning percentage of .713, which translates to 116 victories in a 162-game season. The major leaguers scored 1,241 runs, or nearly 7 per contest, while the service nines scored 694 or about 4 per contest.

After August 26, 1945, there was a drastic drop-off of in-season exhibition games between service squads and major leaguers. In fact, only one was played in 1946. Between August 27, 1945, and the end of the 2013 season, there have been only 38 ISEGs with military teams. The most frequent military opponent during that time was the Army Cadets of the US Military Academy at West Point with 22 appearances in the 38 exhibitions played. Sadly, the only ISEG allowed now is the annual All-Star Game.

The letter President Roosevelt sent to Baseball Commissioner Landis in early January 1942 declared his view of the importance of baseball in wartime as a vital part of the American way of life. Throughout the war years, countless thousands of soldiers on active duty, men and women of every service branch, and baseball fans of all ages, were entertained by ISEGs, as were veterans, many of whom had significant war injuries. These exhibition games fortified the idea that baseball was indeed the national pastime and helped the nation to heal, perhaps in some small part, through its time of national crisis.

- For a comprehensive look at In-Season Exhibition Games, see: https://retrosheet.org/Research/LeConteW/ISEG.pdf

WALTER LeCONTE has been an avid baseball researcher for about 40 of his 65 years and has focused mostly on the New York Yankees. Walter has authored two Yankees books, The Ultimate New York Yankees Record Book and The Yankee Encyclopedia (coauthored with Mark Gallagher). He has recently researched in-season exhibition games, or ISEGS, for short. In fact, he has discovered more than 5,000 of them, dating back to 1871. He has been dubbed “the ISEG King” by his wife, Kathy. A native New Orleanian and Air Force veteran, he has been an ongoing member of the Society for American Baseball Research since the early 1980s and is a regular volunteer for Retrosheet. He resides in Lee’s Summit, Missouri, with his wife and his special feline friends.

Notes

1 “President Franklin Roosevelt Green Light Letter – Baseball Can Be Played During the War,” Baseball-Almanac.com.

2 “When FDR Said Play Ball,” Prologue Magazine, Spring 2002.

3 “Exhibition Games,” Syracuse Herald, May 6, 1918.

4 “Three in a Row For Ruth,” New York Times, September 4, 1922.

5 Irving Vaughan, “Cubs Find a Pal Tough, but Beat Great Lakes,” Chicago Tribune, May 5, 1942.

6 “Athletics Defeat Valley Forge Nine in Exhibition, 10-2,” Daily Republican (Phoenixville, Pennsylvania), June 8, 1944.

7 “Braves Drub Cushing, 13-5, at Framingham,” Boston Globe, August 29, 1944.

8 “Dodgers Set Back St. Albans in 9th,” New York Times, May 1, 1945.

9 James P. Dawson. “27,281 See Cloudbusters Top Babe Ruth’s Team after Yanks Lose to Indians,” New York Times, July 29, 1943.

10 John Drebinger, “40,000 War Bond Buyers Thrill to Baseball Spectacle and Variety,” New York Times, August 27, 1943.

11 John Drebinger, “50,000 fans see Dodgers Triumph: Flock Tallies Five Runs to One for Yankees, None for Giants in Bond Game,” New York Times, June 27, 1944.

12 “Old-Time Dodgers to Aid Bond Game,” New York Times, June 14, 1944.

13 “3-Cornered Baseball Game Yields $56,000,000 in Fifth Bond Drive,” New York Times, June 27, 1944.

14 “Yankees Triumph by 31-6,” New York Times, July 21, 1943.

15 “The Red Sox Got Their Last 4 Runs in 8th Off Hal White. Game was Called at End of 8th to Allow Red Sox to Catch a Train,” Boston Globe, June 6, 1944.

16 “Seabees History,” Seabees Museum.com.

17 “Exhibition Baseball,” New York Times, May 10, 1944.

18 “Giants Defeat Seabees,” New York Times, June 17, 1944.

19 “Schoolboy Battery Helps Sox Take Twinbill at R.I. Camp,” Boston Globe, June 28, 1944.

20 “Braves Achieve Double Victory at R.I. Camps,” Boston Globe, July 13, 1944.

21 “Bosox Crush Coast Guard Bears, 12-8,” Troy (New York) Record, August 28, 1945.