Introduction: Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis

This article was written by Gregory H. Wolf

This article was published in Sportsman’s Park essays

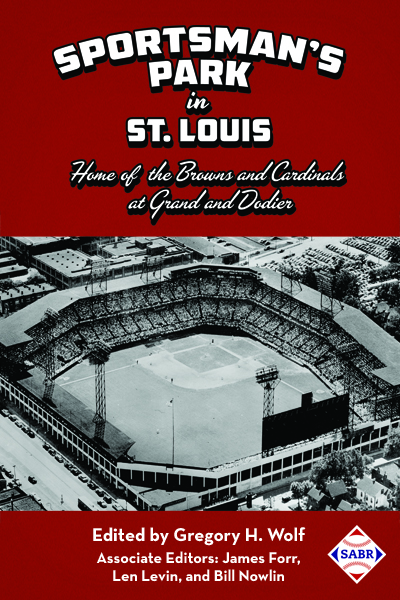

The intersection of Grand Avenue and Dodier Street on the north side of St. Louis is one of the fabled locations in baseball history. Amateurs began playing on a sandlot there as far back as the 1860s. In 1875, the first professional team in the Gateway City, the Brown Stockings of the National Association of Professional Baseball Players called Grand and Dodier its home, and played in a park with a rough wooden grandstand, the Grand Avenue Ball Grounds. That name was changed to Sportsman’s Park the following year when the Brown Stockings became a charter member of the newly founded National League. In the late nineteenth century, the future of baseball at Grand and Dodier was anything but certain. The Brown Stockings went bankrupt and folded after the 1877 season, and the park sat vacant for five years, until another incarnation of the Brown Stockings occupied Sportsman’s Park and dominated the American Association, a rival to the National League, winning four straight championships (1885-1888). After the AA disbanded following the 1891 season, Sportsman’s Park sat vacant again, this time for a decade until the Milwaukee Brewers, a charter member of the American League relocated to St. Louis as the Browns. And that when our story for this book begins … almost.

The intersection of Grand Avenue and Dodier Street on the north side of St. Louis is one of the fabled locations in baseball history. Amateurs began playing on a sandlot there as far back as the 1860s. In 1875, the first professional team in the Gateway City, the Brown Stockings of the National Association of Professional Baseball Players called Grand and Dodier its home, and played in a park with a rough wooden grandstand, the Grand Avenue Ball Grounds. That name was changed to Sportsman’s Park the following year when the Brown Stockings became a charter member of the newly founded National League. In the late nineteenth century, the future of baseball at Grand and Dodier was anything but certain. The Brown Stockings went bankrupt and folded after the 1877 season, and the park sat vacant for five years, until another incarnation of the Brown Stockings occupied Sportsman’s Park and dominated the American Association, a rival to the National League, winning four straight championships (1885-1888). After the AA disbanded following the 1891 season, Sportsman’s Park sat vacant again, this time for a decade until the Milwaukee Brewers, a charter member of the American League relocated to St. Louis as the Browns. And that when our story for this book begins … almost.

In the winter of 1908-1909 Sportsman’s Park was rebuilt and extensively remodeled and renovated. The wooden grandstand was replaced by a modern, doubled-decked steel and concrete one. It was a new dawn for ballparks in the US, as brand-new steel and concrete baseball cathedrals opened in Pittsburgh (Forbes Field) and Philadelphia (Shibe Park) in 1909, and 10 more followed in rapid succession between 1910 and 1915.

This volume focuses on the modern steel and concrete incarnation of Sportsman’s Park which served as the center of professional baseball in St. Louis until the Cardinals played their last game there, on May 8, 1966. The Browns, a perennial second-division team, were the sole occupants of Sportsman’s Park until 1920 when team (and ballpark) owner Phil Ball invited the Cardinals to leave their dilapidated wooden park, Robison Field, and play their games at Grand and Dodier. The rest, as some might say, is history. The Cardinals, a moribund club that had enjoyed only four winning seasons between 1900 and 1920, developed into one of the most successful teams in baseball. They captured 10 pennants and seven World Series championships between 1926 and 1964. After experiencing their longest stretch of success, in the 1920s, the Browns settled into their familiar second-division role for the remainder of their existence in St. Louis. In 1944 the Brownies won their only pennant, setting up a fairy-tale World Series with their tenants, the Cardinals. Wracked by financial problems and poor attendance, the Browns found their days in the Gateway City numbered by the time World War II was over. In 1953 Browns owner Bill Veeck sold Sportsman’s Park to August Busch, who ultimately renamed it Busch Stadium, though St. Louisians and baseball fans continued to call it Sportsman’s Park. At the end of the 1953 season, the Browns played their last game in “Busch Stadium,” were sold in the offseason, and relocated to Baltimore. St. Louis was once again a one-team town. Like other parks of the Golden Age, Sportsman’s Park showed its age by the late 1950s and early 1960s, as newer parks in Milwaukee, Los Angeles, and Minneapolis paved the way for a modern experience for fans. In May 1964, construction began on a new multipurpose sports facility in downtown St. Louis, signaling the gradual end of Sportsman’s Park. On May 8, 1966, the Redbirds played their last game there and inaugurated the new Busch Stadium four days later.

This book rekindles memories of the Sportsman’s Park through detailed summaries of 100 games played there from 1909 to 1966, and insightful feature essays about the history of the ballpark. The process of selecting games was agonizing, yet deliberate. Our goal was to present Sportsman’s Park as a locus of baseball history – for both the National and American Leagues. About two-thirds of the games are dedicated to the Cardinals, the other third to the Browns. Some of the game summaries chronicle historic firsts, such as the Browns’ (1909) and the Cardinals’ (1920) first games in the steel-and-concrete structure; the Browns’ first no-hitter, by little remembered Ernie Koob (1917) and the Redbirds’ first no-no, by popular Jesse Haines (1924); the first time a St. Louis player belted three home runs in a game (the Browns’ Ken Williams in 1922), and the first night game in the ballpark, played by the Browns in 1940. Other essays mark memorable games, such as the three All-Star Games played there (1940, 1948, and 1957) and the final games played by the Browns and Cardinals. Many essays recount great feats, like those of the Redbirds’ Dizzy Dean pitching a shutout on two days’ rest to win his 30th game of the season and capture the pennant for the Gas House Gang (1934), the Cardinals’ Roy Parmelee and the New York Giants’ Carl Hubbell battling for 17 innings (1936), and Stan “The Man” Musial belting five home runs in a doubleheader (1954).

Sportsman’s Park hosted 10 World Series, including the Trolley Car Series, an unlikely matchup between the Cardinals and the Browns. Included are all 35 World Series games hosted by Sportsman’s Park. Many of these games have etched themselves in baseball lore, from the Babe whacking three round-trippers against the Cardinals in Game Four of the 1926 fall classic to the Redbirds’ Game Seven victories over the Boston Red Sox in 1946 and the New Yankees in 1964, hammering the last nail in the dynasty that had ruled the AL for more than four decades.

Furthermore, the games not only just highlight the accomplishments and heroics of stars like Pete Alexander, Mort Cooper, Johnny Mize, and George Sisler, but also revive memories of forgotten or overlooked players like Bob Groom, Sig Jakucki, Jack Kramer, and Allan Sothoron of the Browns and Les Bell, Eddie Dyer, Wild Bill Hallahan, and George Munger of the Cardinals. Also included are memorable or historic performances by the Browns’ and Redbirds’ opponents, such as the Chicago White Sox’ Eddie Cicotte tossing the first no-hitter in Sportsman’s Park (1917) and the debut of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Jackie Robinson in the Gateway City (1947).

Ten feature essays round out the volume and provide context for the stadium’s history. Topics include the Milwaukee Brewers’ move to St. Louis to become the Browns in 1901 and the Browns’ relocation to Baltimore for the 1954 campaign, as well as beer magnate August Busch’s purchase of the Cardinals in 1953, and the subsequent renaming of Sportsman’s Park to Busch Stadium that same year. There are also thorough biographies of former Browns owners Robert Hedges and Phil Ball, and Sam Breadon of the Cardinals. An essay on the history of Sportsman’s Park and the statistics-oriented piece “By the Numbers” round out this extraordinary volume.

This book is the result of tireless work of many members of the Society for American Baseball Research. SABR members researched and wrote all of the essays in this volume. These uncompensated volunteers are united by their shared interest in baseball history and resolute commitment to preserving its history. Without their unwavering dedication this volume would not have been possible.

I am indebted to the associate editors and extend to them my sincerest appreciation. Bill Nowlin, the second reader; fact-checker James Forr; and copy editor Len Levin each read every word of all the essays and made numerous corrections to language, style, and content. Their attention to detail has been invaluable. It has been a pleasure to once again work on a book project with such professionals, with whom I corresponded practically every day, and typically more than once.

I thank all of the authors for their contributions, meticulous research, cooperation through the revising and editing process, and finally their patience. It was a long journey from the day the book was launched to its completion, and we’ve finally reached our destination. We did it! Please refer to list of contributors at the end of the book for more information.

This book would not have been possible without the generous support of the staff and Board of Directors of SABR, SABR Publications Director Cecilia Tan, and designer Gilly Rosenthol (Rosenthol Design). Special thanks to John Horne of the National Baseball Hall of Fame for supplying the overwhelming majority of photos.

We invite you to sit back, relax for a few minutes, and enjoy reading about the great games and the exciting history of Sportsman’s Park.

A lifelong Pirates fan, GREGORY H. WOLF was born in Pittsburgh, but now resides in the Chicagoland area with his wife, Margaret, and daughter, Gabriela. A professor of German studies and holder of the Dennis and Jean Bauman Endowed Chair in the Humanities at North Central College in Naperville, Illinois, he has edited seven books for SABR. He is currently working on projects about Crosley Field in Cincinnati, Wrigley Field and Comiskey Park in Chicago, and the 1982 Milwaukee Brewers. As of January 2017, he serves as co-director of SABR’s BioProject, which you can follow on Facebook and Twitter.