It’s a Different Game: Aluminum Bat Performance vs. Wood Bat Performance

This article was written by Bill Thurston

This article was published in 2003 Baseball Research Journal

Jeff Bagwell, Mike Bordick, Pie Traynor, Carlton Fisk, Mickey Cochrane, Tino Martinez, Eric Milton, Mark Mulder, Frank Thomas, and Mo Vaughn all have something in common. They are just a few who competed in the Cape Cod League, the premier amateur baseball program in the nation since 1885. In 2002 there were over 180 former Cape Cod League players on major league rosters, including American League Cy Young winner Barry Zito, AL Rookie of the Year Eric Hinske, and All-Stars Nomar Garciaparra, Todd Helton, and Lance Berkman.

In 1967, Thurman Munson led the league in hitting and was named the Cape’s Most Valuable Player. A few other well-known MVPs over the years include Nat Showalter (better known as “Buck”), Steve Balboni, Ron Darling, Terry Steinbach, Greg Vaughn, Jason Varitek, and Darin Erstad. The award for the league’s batting champion is named in Munson’s honor, and among the recent winners are Bobby Kielty (1998), Lance Berkman (1996), Josh Paul (1995), and Lou Merloni (1992). The league established a Hall of Fame in 2000, and members include Mike Flanagan, Chuck Knoblauch, and Robin Ventura.

The nonprofit league was reorganized in 1963 with help from the NCAA and remains an NCAA approved summer league, one of a growing number around the country, most of which use wooden bats. In 2003, the teams included the Bourne Braves, Brewster Whitecaps, Cotuit Kettleers, Falmouth Commodores, Harwich Mariners, Hyannis Mets, Orleans Cardinals, Wareham Gatemen, and Yarmouth-Dennis Red Sox.

The league is important to professional scouts because it doesn’t allow the use of aluminum bats, though metal was used from 1975 to 1985. But the league returned to wood in 1986, and it has not looked back. The opportunity for collegiate players to prove they can make the switch from aluminum to wood makes the league more attractive and one reason it is much sought after by the best college prospects.

For the past six years I have been analyzing wood bat performance in the league compared to the high tech aluminum bats used during the players’ collegiate season. What follows is the results of that study. The parameters are: (1) only Division I hitters and pitchers were included; (2) hitters needed a minimum of 70 at bats in the Cape Cod League to be included; (3) pitchers needed a minimum of 25 innings pitched. This means only regular players were considered.

In 2002, there were a total of 94 Division I hitters and 74 Division I pitchers who met the criteria. NCAA spring statistics (aluminum bat) of the players were compared to their summer Cape Cod League statistics (wood bats). Thus, the comparison is for the same players during the same year. While the level of players, both hitters and pitchers, is better in the Cape Cod League, the major variable is the bat.

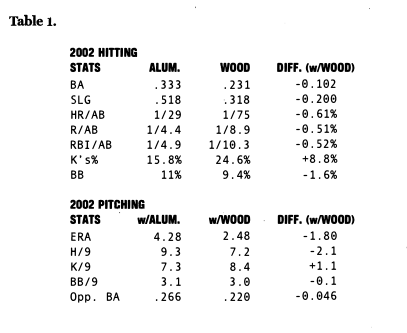

The difference in offensive performance in 2002 from the aluminum to the wood bat is dramatic. Using 94 Division I hitters, comparisons were made in the following offensive categories:

From this statistical analysis, it is unquestionably evident that during actual game use, aluminum bats dramatically outperform wood bats.

Furthermore, one has to question the reliability of the results of various lab tests comparing the performance of wood and aluminum. In the case of the Baum Hitting Machine Test used by the NCAA for the BESR standard, the test was compromised by comparing a heavier wood bat to a lighter aluminum bat. On a machine that has fixed-swing speed, both bats, regardless of weight, are swung at an identical speed; therefore, the more mass, the higher exit speed. Of course, a batter cannot swing a heavier unbalanced bat as fast or with as much control as with a lighter, better-balanced bat. Also, the Baum test standard was raised so that many of the 2000 aluminum bats could pass the test.

According to Professor James Sherwood (the test administrator), scaling the weight of the aluminum bat from 29.8 to 34 ounces could theoretically result in a ball exit speed of 113.25 mph, a difference of +16.37 mph with a comparable wood bat. Plus, metal bats have a total sweet spot much larger than wood (thus the ball is hit faster and more frequently). The sweet spot is the area on the bat that produces the maximum exit speed and causes the least amount of bat vibration.

I believe another factor with the Baum bat test that prevents the results from correlating to actual performance in the field is that the swing and pitch speeds are set so low that the resulting collision force of 132 mph does not trigger the trampoline effect in aluminum bats. The collegiate game is played at speeds of 160-180 mph.

Until the MOI (moment of inertia) of aluminum bats is mandated to match that of the various length of pro wood bats, the performance, and more important batted-ball exit speed, will never be like wood. It is obvious, even with the recent changes in aluminum bat standards by the NCAA, there continue to be major differences in bat performance on the playing field. The present MOI standard for aluminum bats is not comparable to the normal MOI of wood bats.

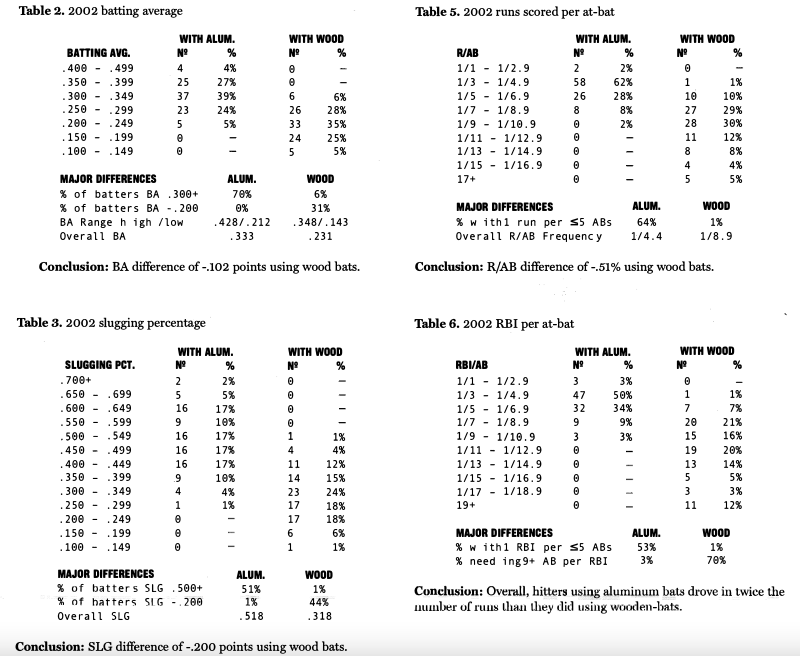

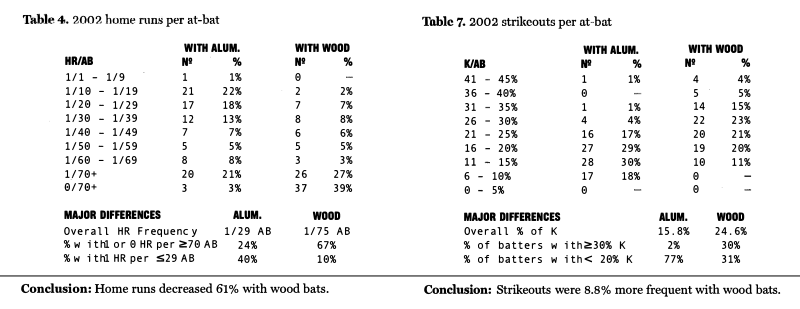

The following charts 2-7 compare the same 2002 players in their Division I games versus their performance in the Cape Cod League. This demonstrates the dramatic difference in actual games between aluminum and wood bat performance during the 2002 season only.

(Click images to enlarge)

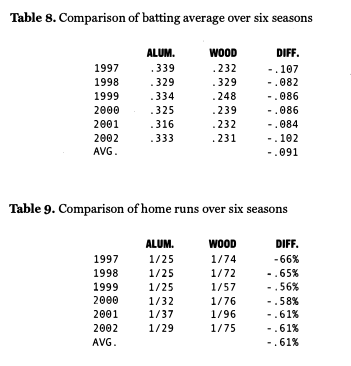

SIX-YEAR COMPARATIVE STUDY

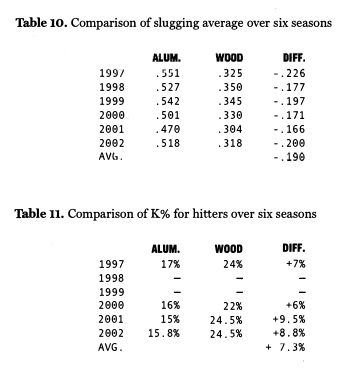

Using the same criteria for Division I hitters and pitchers who played in the summer Cape Cod League for the past six seasons, the bat performance difference between aluminum and wood bats is consistent and dramatic. Same player, same year, the major variable, the bat.

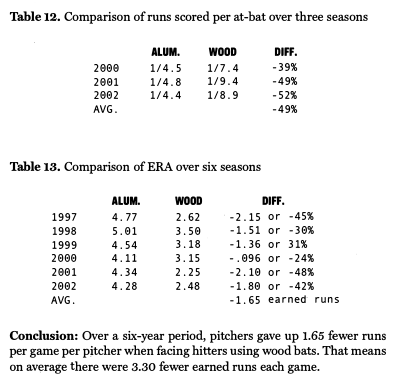

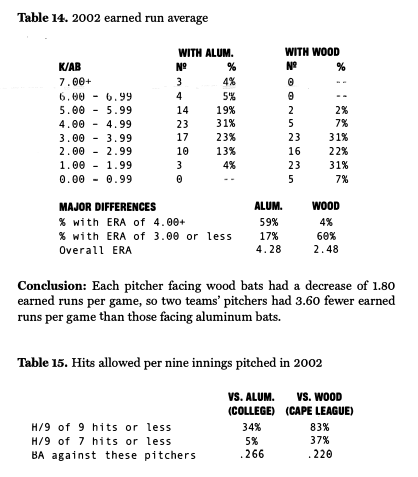

PITCHING

Of the Division I pitchers, 74 pitched a minimum of 25 innings in the Cape Cod League during the 2002 season.

Also, hitters using aluminum bats hit twice as many home runs against these pitchers as when they used wood bats. Remember, the college offensive lineups are not nearly as talented as the hitters playing in the Cape Cod League.

RISK OF INJURY FROM BATTED BALLS

While this study focused on the different performance levels between aluminum and wood bats, another major problem that needs to be addressed is the increased risk of injuries from batted balls off the high-performance aluminum bats. It is well-documented from lab tests, field tests, and various studies that the ball is hit with greater velocity – and hit faster, more frequently – with an aluminum bat. There are many reasons for this:

- Factors of increased batted-ball exit speed.

- Greater swing speed. A hitter can swing a lighter, better-balanced bat faster than a heavier or end-heavy bat.

- The trampoline and hoop effect of n thin, hollow tube versus a solid wood bat.

- The balance point (MOI) of an aluminum bat is closer to the handle, allowing greater head-of-the-bat speed and better bat control. Note: In a test completed at Amherst College in November 2002, six hitters had 90 recorded hits off a tee (stationary ball) with both wood bats (2) and aluminum (2) bats. The average increase in batted-ball exit speed was 5.9 mph when using aluminum bats. This is a major and significant increase because, with pitched-ball speed and the trampoline effect added, the batted-ball exit speed off aluminum will dramatically increase over that of wood.

- The ball comes off an aluminum bat faster and faster more frequently.

- The diameter of the bat is larger and stays larger, longer, down the length of the bat.

- Sherwood states that the sweet spot is four times larger than in a normal wood bat.

- The bat is better balanced. A hitter can control the swing better, start the swing Inter, and track the pitch longer (good contact more frequently leads to higher batting averages).

- Over a six-year period, hitters struck out 7.3% more often when using wood bats. With strikeouts, pitchers avoid the risk of being struck and injured by a batted ball.

- The Cape Cod League study demonstrates how differently the game is played using wood. Over a six-year period:

Batting averages decreased by .091 points.

• Slugging percentage decreased by .190 points.

• Home runs decreased by 61 %.

• Earned run average decreased by 1.65 per pitcher, and 3.30 per game. - Players are now bigger and stronger than years ago and hit the ball harder and faster when they make good contact. Fielders do not have as much time to field the batted ball or to defend themselves.

- If a player is struck by a batted ball hit with greater velocity, chances are there will be a more severe injury.

If experienced major league pitchers are being struck by line drives off wood bats, then we should not be using bats that outperform wood. Amateur pitchers are less experienced than pro pitchers and often are not aware of the danger. They don’t anticipate and react properly.

Against aluminum bats, most pitchers cannot effectively pitch inside with the fastball; they have to pitch away more often. There are more balls hit up the middle (toward the pitcher) on outside pitches than on inside pitches. Again, this factor increases the risk of injury.

By 1998, the NCAA Umpire Improvement Program Committee was so concerned about the safety of their field (base) umpires that they instituted an umpire position change. They moved the field umpires back, farther away from home plate to give them more time to react to batted balls.

MAJOR QUESTIONS

Why don’t various lab test results correlate to bat performance in the field, in games, or even during batting practice? Could all of these injuries we have experienced since the mid-’90s through 2002 have occurred with balls hit off wood bats? Maybe, but we will never know. Chances are that they would have occurred less frequently with wood bats: The pitchers would have more time to react, since off wood the ball is not hit as fast or hit hard as frequently.

I believe that based on the statistical evidence of this study, and statistics developed over the past six years, my conclusions are convincing. The collegiate game played with the present high-performance aluminum bats is not remotely close to the traditional game played with wood bats. For the safety of the players, to bring the game back in balance, and to restore the integrity of the game, I hope that in the near future that true wood performance standards are put in place at all levels of amateur baseball.

BILL THURSTON has served as the head baseball coach at Amherst College for 39 years. He was the NCAA Baseball Rules Editor from 1985 to 2000, head coach for the Australian National team in 1984-85, and pitching coach for the USA team in 1986. He is a pitching consultant for the American Sports Medicine Institute in Birmingham, AL.