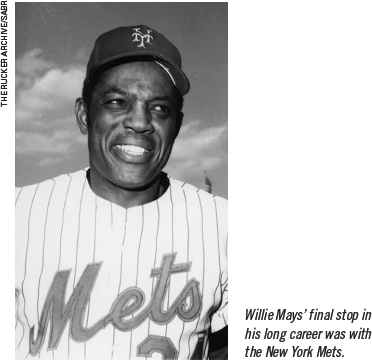

‘It’s Like Coming Back to Paradise’: Willie Mays and the Mets

This article was written by David Krell

This article was published in Spring 2022 Baseball Research Journal

Mother’s Day, 1972. Willie Mays had just smacked his 647th home run. For the 35,505 fans braving the rain at Shea Stadium on Mother’s Day in 1972, it signaled that, for a brief moment, the aging Mays could still delight fans. The 5-4 victory for the home team over the San Francisco Giants was Mays’s first game in a New York Mets uniform.

Mets owner Joan Payson and her counterpart in the City by the Bay, Horace Stoneham, concocted the deal to let Mays fill out the rest of his playing days in the city that gave him his major-league start and maintained its adoration; Stoneham got Mets pitcher Charlie Williams and a reported $100,000 bounty in exchange for the icon.1

But returning to New York had already been a goal for the Say Hey Kid, now 41 years old and a member of the Giants squad since 1951.

Former manager Herman Franks revealed, “It was two years ago that Willie and I talked about his playing out the string in New York. So, we have done some thinking about it together. The Mets’ deal is a good one for him, because, knowing the kind of man Willie is and how he thinks, is to know how unhappy he’d be away from baseball.”2

Though Mays was at the end of his playing career, donning a uniform for a New York team again brought excitement, anticipation, and nostalgia to the city’s National League fans. Those of certain ages—from their mid-20s upward—remembered the glory days of the Alabama native who graced outfields, pounded pitching, and emerged as a team leader in the NL. When the Mets began in 1962, they had inherited fans of the Dodgers and Giants, who had left for California after the 1957 season.

Mays coming to the Mets created nostalgia that pacified the team’s fan base, who had not only endured national tragedies in recent years—assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Bobby Kennedy, and Martin Luther King, Jr.—but also epic challenges that had tested the resolve of New Yorkers throughout the five boroughs. Strikes by transit workers, garbage workers, and teachers threatened the daily business of America’s largest city. New York’s financial status declined towards bankruptcy. Plus, the dissolution of exemplary newspapers reduced options for daily learning of the city’s goings-on.

On top of these pressures, Mets fans were in mourning in 1972. Mays’s link to 1950s baseball in New York—often referred to as the “Golden Age of Baseball”— provided an emotional balm of sorts, arriving a little more than a month after the passing of skipper Gil Hodges, who had led the Mets to their first World Series victory in 1969. A mixture of disappointment, grief, and anger had pervaded Mets Nation when Hodges died from a heart attack two days shy of his 48th birthday in early April; Yogi Berra, a Mets coach since 1965, took over as manager.

Hodges was a fixture on the gloried Brooklyn Dodgers teams of the late 1940s and 1950s. Same with Berra and the New York Yankees. From 1947 to 1957, the city was represented 10 of 11 times in the World Series.3

San Franciscans’ memories were steeped in the team’s formidability during Mays’s tenure: when MLB initiated the ’72 schedule, San Francisco hadn’t endured a losing season since the team arrived in 1958. Mays et al. began 1972 with the status of being NL West champions.

After the Giants edged out the Dodgers by one game to win the NL West in 1971, Pittsburgh took the NL flag and beat Baltimore in seven games in the World Series. Mays had ended the season indicating his stamina, skills, and instincts were still potent—if not overpowering as in days of yore—to NL pitchers: the two-time Most Valuable Player played in 136 games in ’71, leading the senior circuit in walks (112) and on-base average (.425).

But optimism for San Francisco’s ’72 prospects waned quicker than the winds shifted at Candlestick Park—the team was 8-16 at the time of the Mays trade. Mays, too, had a downslide, with a batting average of .184 over 19 games when he left for New York.

It mattered not to Payson, who had a fondness for the center fielder dating back to her tenure as a former minority owner of the Giants before the team abandoned subway trains for cable cars. Fueled by sentiment rather than necessity—the Mets were 13-6 at the time of the trade—signing her favorite player recalled the newest entry in America’s movie lexicon from the recently released epic The Godfather: “I’ll make him an offer he can’t refuse.”

Though Mays might have been a sentimental choice for Payson, there was a similar tether as strong as Samson between him and Stoneham: Mets chairman Donald Grant acknowledged this but also noted the opportunity for the Giants owner to show generosity towards his iconic player. “The club isn’t drawing and its [sic ] down in the standings. He can say ‘I’ve done the greatest favor I can do for Willie. I’m sending him home where he wants to be. I’m sending him to the Mets.’”4

Mays confirmed Grant’s description. “When you come back to New York, it’s like coming back to paradise,” said the four-time major-league leader in slugging percentage at the press conference announcing the trade.5

Despite his ’72 stats to date, Mays had confidence in his value. Or so he claimed. “It’s a wonderful feeling and I’m very thankful I can come back to New York,” said the slugger. “I don’t think I’m just on display here. There’s no doubt in my mind that I can help the Mets if I’m used in the right way.”6

And so, he did.

The Mets vaulted to a 4-0 lead in the bottom of the first when Rusty Staub hit a no-out grand slam after Sam McDowell walked Mays, Bud Harrelson, and Tommie Agee. The San Francisco lefty settled and struck out Cleon Jones, Jim Fregosi, and Ted Martinez.

McDowell’s cohorts tied the game in the top of the fifth. Ray Sadecki walked Fran Healy; Giants skipper Charlie Fox sent Bernie Williams to pinch hit for McDowell. Fox’s decision proved wise when Williams tripled and scored Healy. Chris Speier doubled home Williams; Tito Fuentes homered—one of his seven dingers for the year.

Mays led off the bottom of the fifth with a homer off reliever Don Carrithers. His solo bash gave the Mets a slim but sufficient one-run lead that sustained the victory. Although the veteran must have been feeling sentimental with New Yorkers cheering his round tripper, there was a palpable wistfulness: “It’s a strange feeling to be batting against the club I played with for 20 years. You look up and see ‘Giants’ written on their shirts, and feel you should be out there.”7

Mays’s performance was a joyous occasion, but Mets fans knew that it was an anomaly. The slugger’s skills were fading. Ken Samuelson recalled positive energy contrasting sad facts in Peter Golenbock’s oral history Amazin’: The Miraculous History of New York’s Most Beloved Baseball Team: “Even though we were getting Willie Mays, we realized we really weren’t getting the Willie Mays. The season before Willie had begun to slow down, and so the idea [of him] was probably more than the reality. But I was real excited. It was just the idea of him coming back and having such a magical player in our lineup.”8

Greg Prince—author of several Mets books and co-founder of the Faith and Fear in Flushing web site— was a nine-year-old in Long Beach, New York, when he learned about the Giants legend coming to Queens. “I found out from reading an article in the New York Post, which my father read,” says Prince. “It was shocking because Willie Mays was the best living ballplayer at the time. The Mets were in first place. After the Mother’s Day game, it seemed like everything was working out.”9

The victory on May 14 was the third victory in an 11-game winning streak; the Mets went 21-7 in May and finished the 1972 season in third place with an 83-73 record. The Pirates were dominant, though, winning the NL East with a 96 wins and 59 losses.

Mays played in 69 games for the Mets in 1972, batting .267 with eight home runs. His average dropped to .211 in 1973. Mays smacked six homers and played in 66 games. After nearly winning the World Series in 1973—New York lost to Oakland in seven games—the 42-year-old Mays retired.10

But the nostalgia at seeing #24 back in a New York uniform was not felt universally in the Mets clubhouse. In his 1975 book The Miracle at Coogan’s Bluff, Thomas Kiernan cited the frustration of an unnamed Mays teammate at the end of the ’72 season: “If he walks, say, then gets sacrificed to second—if the next hitter doesn’t get a hit and give Willie a chance to score, he gets booed. It’s all Willie Mays, and that’s not the way it should be. I wish to hell he’d hang ’em up. He had his day in the sun here, now he should go out gracefully and let us be a baseball team again.”11 Thomas Wolfe was wrong. You can go home again. But some of the new residents might not be as welcoming as the old ones.

DAVID KRELL is the chair of the Northern New Jersey Chapter of SABR. He joined SABR in 2012. David is the author of 1962: Baseball and America in the Time of JFK and Our Bums: The Brooklyn Dodgers in History, Memory and Popular Culture. He also edited the anthologies The New York Mets in Popular Culture and The New York Yankees in Popular Culture.

Notes

1. Joseph Durso, “Mays Back in Town and Mets Have Him,” The New York Times, May 12, 1972, 33.

2. “With Friend Like Franks, Mays Needn’t Worry,” Daily News (New York), May 14, 1972, 123.

3. The Yankees won seven titles. The Dodgers and Giants each won once.

4. United Press International, “Mets Await Visit Today from Stoneham,” Daily News (New York), May 9, 1972, 16.

5. Steve Cady, “‘Like Coming Back to Paradise,’ Says Mays—And Fans Agree,” The New York Times, May 12, 1972, 35.

6. Durso, “Mays Back in Town and Mets Have Him”.

7. Joseph Durso, “Mets Win on Mays’s Homer, 5-4,” The New York Times, May 15, 1972, 47.

8. Peter Golenbock, Amazin’: The Miraculous History of New York’s Most Beloved Baseball Team (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2002), 289. Emphasis in the original.

9. Greg Prince, telephone interview with writer, January 26, 2020.

10. Babe Ruth began his major league career with the Red Sox and returned to Boston for his final season, playing in 28 games for the Braves in 1935. Hank Aaron delighted Wisconsinites by closing out his career in Milwaukee. He started with the Milwaukee Braves in 1954 and stayed with the organization through 1974. But the Braves had moved to Atlanta in 1966, leaving Milwaukee without a major league team until the Seattle Pilots moved after their inaugural season and became the Brewers in 1970. Aaron had a two-year tenure: 1975-76. His sentiments matched Mays’s: “I am thrilled to come back to the city where I started my baseball career and I am happy that the Atlanta Braves saw fit to work so closely with me to meet my request.” “Brewers Bring Hank Back to Milwaukee,” Wisconsin State Journal, November 3, 1974, 25.

11. Thomas Kiernan, The Miracle at Coogan’s Bluff(New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1975), 161-62.