Jack Kerouac: The Beat of Fantasy Baseball

This article was written by Jim Reisler

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 28, 2008)

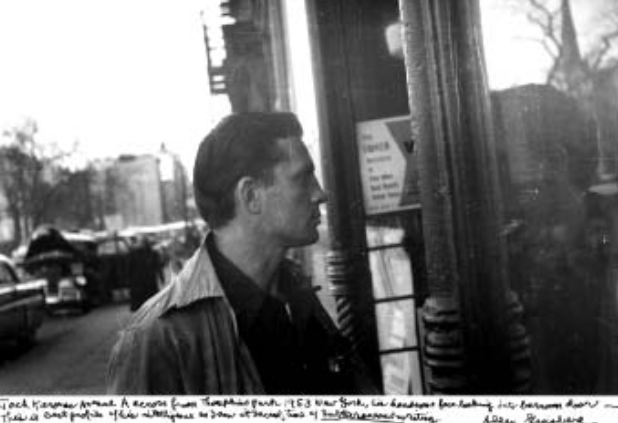

Before achieving fame as a leading literary voice of the Beat Generation, Jack Kerouac aspired to be a sportswriter and already as a teenager had created a highly detailed imaginary baseball universe. (COURTESY OF THE ALLEN GINSBERG ESTATE)

Buck Maxfield has the fastest, burningest, whistlingest speed-ball I’ve ever seen come down the aisle,” a sportswriter calling himself Jack Lewis wrote in 1937. “He’s a big, tough, raw-boned kid, and has what it takes to lift his big leg and burn it down.”

If you don’t recognize the names Maxfield or, for that matter, Lewis, worry not. Both are creations of the future literary icon Jack Kerouac (1922–69), who wrote those lines at age 15, when he dreamed of becoming a sportswriter with a baseball beat—a path markedly different from the one he took as the writer of that landmark book of youthful restlessness, On the Road, and as a leading voice of the Beat Generation in the 1950s.

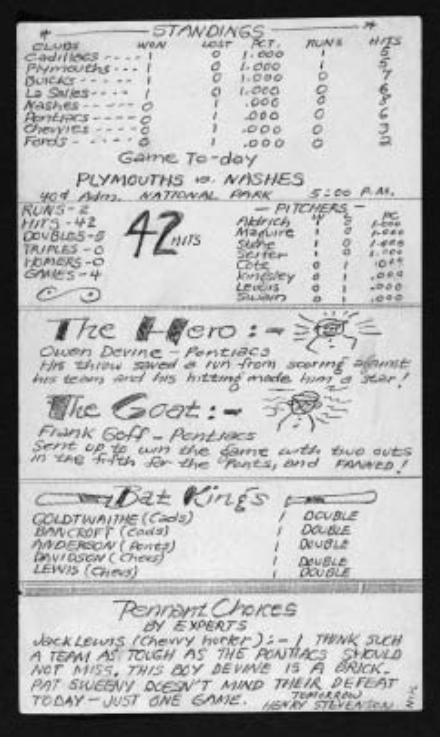

Buck and other fictional players, such as the base-stealer Pancho Villa and Pittsburgh slugger Frank “Pie” Tibbs—a takeoff on Pie Traynor, perhaps?—are all creations of Kerouac’s decades-long obsession with fantasy baseball. Years before anyone had ever heard of Strat-O-Matic or Rotisserie baseball, Kerouac’s New York Chevvies, Cleveland Studebakers, St. Louis LaSalles, and Pittsburgh Plymouths ruled his fantasy base- ball universe—revealing both the hidden passion of a great American writer and an artist in search ofa style.

The evidence is a series of approximately twenty of Kerouac’s fantasy-baseball artifacts, which constituted a healthy chunk of the exhibition Beatific Soul: Jack Kerouac on the Road at the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue. The exhibition, which was on view last fall through this spring (November 9, 2007, through March 16, 2008) to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of On the Road, consisted of items taken from the library’s Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, which includes the Jack Kerouac archive, purchased in 2001.

“Baseball Chatter” and More

Kerouac’s celebration of the American road is well known. His interest in fantasy baseball, which he played occasionally with fellow Beat writer Philip Whalen, is not. Kerouac’s ardor for the game emerges in the exhibition’s yellowed newspapers, Jack Lewis’s Baseball Chatter, which resemble period copies of The Sporting News, and cover the doings of the forty or so fantasy games each of Kerouac’s six or eight teams played most years. The baseball items include detailed team rosters, explanations of his increasingly complex, self-made fantasy games, and even a fictional correspondence with Tom Yawkey, who owned the Boston Red Sox. (Kerouac, a native of Lowell, Massachusetts, was a lifelong Sox fan.)

“We knew Jack Kerouac had a strong interest in baseball—he wrote short stories about it, and On the Road contains scenes about playing baseball—but we weren’t aware of the extent,” says Isaac Gewirtz, the exhibition curator and author of its companion volume. “The young Kerouac wanted to be a sportswriter. He has a punchy style and there are flashes of originality. With baseball, he is a writer trying to find his voice.”

Along with diaries, photos, and paintings of the Beats and amidst the exhibition’s iconic 120-foot On the Road manuscript scroll, on which Kerouac composed and typed a late draft of the novel in three weeks before amending it in typescripts, are penetrating glimpses into Kerouac’s emerging gift for vivid description. The teenage Kerouac typed the broadsheets on the back of racing forms taken from his father’s printing business in Lowell. Some examples, taken mostly from 1938:

Of another “Buck,” a fantasy player named Buck Barbara of the Philadelphia Pontiacs, Kerouac writes that “he almost drove Charley Fiskell, Boston’s hot corner man, into a shambled heap in the last game with his sizzling drives through the grass.”

Of Bob Chase, an accomplished pitcher for the Chevvies, Kerouac claims “to be puzzled by his habit of excessively praising” his opponents. “The other day, [Chase] was moaning about the Pittsburgh Plymouths, saying they were the vanguard of rifted humanity, and complaining that they should not be roaming free in this great land of ours,” Kerouac adds. “Yet today he defeated them by a one-sided score and smiled wanly.”

Speaking of the Chryslers, Kerouac writes that the team, “by some strange[r] reason than I can think, did not join the league this season,” with its former players spread to all directions.

Lefty Fayne, the old southpaw, is with the LaSalles, Robin King has retired to his farm in Iowa Mike. Kuzinecz, and old Sam Wyatt, also have retired. And Vic Bodwell, an old [St. Louis] Cad slugger, is playing golf. And so many more.

Frank “Pie” Tibbs’s hitting “has been absolutely flawless,” Kerouac writes in 1939. “He wields a long black bat, swinging from the portside, and swings in a wide, upward arc which spells distraction for every pitcher he has met this season so far.”

In Kerouac’s teenage fantasy-baseball world, teams took the names of cars, as in the Chevvies, Pontiacs, and Fords. In the 1950s and adulthood, he continued to cover this baseball universe in fictional newspapers, but he changed the teams’ names to colors, including the appropriately named New York Greens and Chicago Blues—because, Gewirtz surmises, “he probably thought they were less childish, more realistic names.” Taking most of his players’ names from listings in telephone books, Kerouac occasionally planted an inside man or two, as in Villa, the Pontiacs’ center fielder and, not surprisingly, the league’s fastest man.

In some cases Kerouac drafted friends and acquaintances into his league. Named as manager of Pittsburgh and later the Chicago Blues was one Seymour Wyse; the real Wyse was Kerouac’s high-school classmate at Horace Mann School in New York City, and the man credited with introducing the young writer to live jazz. Riding the bench for the 1953 Plymouths is Robert Giroux, Kerouac’s editor at Harcourt, Brace. Playing for the Washington Chryslers is Stanley Twardowicz, an abstract painter Kerouac admired; in the early 1960s the two men found themselves living near one another on Long Island and became friends.

In the late 1950s, Kerouac traded Villa to the Boston Fords, perhaps because by then he had appointed himself manager. Around the same time, an influx of Latino players entered the league, as Roberto Clemente, Orlando Cepeda, and others were making an impact in baseball’s real world. For some reason, Kerouac made the Philadelphia Pontiacs the prime repository of Latino talent, who included a Cuban shortstop named “El Negro” and utility man Jorge Orizaba, the name of the Mexico City street where Kerouac lived in the spring of 1956.

“Many a youth made up such baseball cards,” baseball reporter Stan Isaacs once wrote. “The charm of Kerouac’s cards was the imagination he brought to them, creating wondrous personalities, keeping records, writing stories about the action.” (COURTESY OF JOHN G. SAMPAS, LEGAL REPRESENTATIVE OF THE ESTATES OF JACK AND STELLA KEROUAC)

Stat Man

From talking to Kerouac’s relatives, Gewirtz estimates that Kerouac started playing fantasy baseball at around age nine. One reason it held his interest for so long, Gewirtz adds, was Kerouac’s lifelong fascination with lists and statistics.“You could write a whole book on Kerouac as a list maker,” Gewirtz says. “Every week, it seems, he was compiling a list, from favorite foods to things to do and his favorite books.” Said Kerouac to Whalen on his zeal for the fantasy game, “I’ve got an obsession with statistics.”

Critics might argue that, with his slangy and occasion- ally clichéd prose, Kerouac was satirizing the glib sportswriting style of the day. But Gewirtz thinks other- wise, maintaining that Kerouac’s writing reflects a genuine enthusiasm for sports and his teenage goal of becoming a sportswriter. A gifted athlete, Kerouac starred as a running back on the Lowell High School football team before attending Horace Mann for a year, where he played baseball—“not a particularly good hitter,” Gewirtz says of Kerouac, “but strong in the field”—and earning a football scholarship to Columbia. Soon after Kerouac’s playing days came to an abrupt end in his sophomore year in 1942, when he broke his tibia, feuded with Columbia coach Lou Little, and left school, he joined the Lowell Sun as a sportswriter.

Finally, Kerouac had the kind of job he had dreamed about as a teenager, but it was short-lived—he inexplicably bolted the position after a few months. He failed to show up for an interview with a local baseball coach one day. It turned out that he had skipped town. A day or so later he appeared with a construction crew building the Pentagon in Virginia. Still, he retained his love for fantasy baseball and sports, often catching big-league games in New York and listening to baseball games and boxing matches with fellow beat Neal Cassady, the inspiration for On the Road character Dean Moriarty. The two men also enjoyed throwing around a football.

As fantasy baseball has developed over time, so Kerouac constantly tinkered with his personal version of it. In the 1950s and ’60s, a rudimentary design—bats were matchsticks, and the ball was a marble—gradually gave way to a more complex, two-man system involving cards, complete with player-skill levels, ball/strike ratios, and game scenarios such as “infield tap” and “pop foul.” And, as Major League Baseball integrated, so did Kerouac’s fantasy league—but earlier, in 1943, the same year that Bill Veeck said he was blocked in his effort to buy the Phillies and integrate the team with stars from the Negro Leagues. Two years later, the Dodgers signed Jackie Robinson to a minor-league contract, and it was not until 1947 that he played in his first major-league game.

Gewirtz and his staff were able to piece together the broad evolution of Kerouac’s fantasy game from the writer’s unpublished memoir, Memory Babe, which details his interests as a teenager and how he played the game. In addition to reporting on his fantasy games, the adolescent Kerouac incorporated baseball into other early literary endeavors. “Freddy watched Lefty’s first. pitch come bouncing back to him,” he writes in one such novella, “hissing sibilantly as it cut towards him in wild capers.”

Digging Mel Allen

Meanwhile, Kerouac sprinkled periodic references to baseball throughout his writing. In a 1951 letter to Cassady, Kerouac writes that he had been “digging the World Series and the tones of the various announcers”— particularly the “old reliable, southern-accent” Mel Allen. “How I dig all this,” Kerouac writes. “My mind, wrapped in wild observation of everything, is drawn by the back-country announcer, back to the regular, brakeman things of life.”

In a 1959 magazine piece, Kerouac writes, “When Bobby Thomson hit that home run in 1951, I trembled with joy and couldn’t get over it for days and wrote poems about how it is possible for the human spirit to win after all!” (See Tom Harris’s interview with Bobby Thomson at page 70-72.)

Kerouac died on October 21, 1969, five days after the Mets won their first World Series, of an abdominal hemorrhage brought on by alcoholism; he was only 47 and living in St. Petersburg, Florida, with his third wife, Stella, and his mother. To the end, baseball was one of the few constants of an otherwise rambling, psychologically unsettled life.

In recent years, columnists and writers have begun to explore Kerouac’s interest in baseball. In 2002, Stan Isaacs, the former Newsday baseball reporter, penned a colorful piece for TheColumnists.com about a fantasy game he had played against Kerouac on a wintry afternoon in 1961, when the writer was living in Huntington, New York. “He conducted a running commentary about the players as the game proceeded,” Isaacs writes. In one case, Kerouac’s Chicago Blues staged a rally that started when shortstop Francis X. Cudley—“an Irishman from Boston who stood up at the plate very erect, like a Jesuit,” according to Kerouac—fumbled a grounder by Johnny Keggs.

Johnny Keggs? “An old guy; his neck is seared from the Arkansas sun,” Kerouac told Isaacs. Keggs’s brother Earl, a former player, “now is back in Texarkana, selling hardware,” Kerouac said. For the record, Isaacs’s Pittsburgh Browns were too much for the Blues, and they won easily, 9–2.

“Many a youth made up such baseball cards,” Isaacs writes. “The charm of Kerouac’s cards was the imagination he brought to them, creating wondrous personalities, keeping records, writing stories about the action.”

In 2003, the Lowell Spinners (Class A, New York– Pennsylvania League) produced an instant collectible— the Jack Kerouac bobblehead doll. Ordering one thou- sand of the dolls for a giveaway in a game against Williamsport, the Spinners inadvertently created a new hit Ebay item in the process. In a recent online sighting, Kerouac bobbleheads were going for about $100.

But nowhere are Kerouac’s passion for baseball, emerging writing style, and acute sense of humor more evident than in the ongoing fictional correspondence, in 1940, between Kerouac, purporting to represent the interests of the Detroit Tigers, and Tom Yawkey of the Red Sox, along with a character named Jack Dudworth of the Yankees.

In a letter to the Yankees, Kerouac proposes trading future Hall of Famers Hank Greenberg and Charlie Gehringer and three others for another legend, Joe DiMaggio. “Dear John,” Dudworth writes back. “I would not let go of DiMaggio for those stumblebums if you threw in city hall, the library, B&M carshop and the Ford MC of Dt [Motor Company of Detroit].”

That means Greenberg and Gehringer stayed with the Tigers, right?

JIM REISLER, a SABR member for more than twenty years, is the author of A Great Day in Cooperstown: The Improbable Birth of Baseball’s Hall of Fame (Carroll and Graf, 2006) and Babe Ruth: Launching the Legend (Macmillan, 2004).