Jackie Robinson and Baseball Owners

This article was written by Andy McCue

This article was published in Jackie Robinson: Perspectives on 42 (2021)

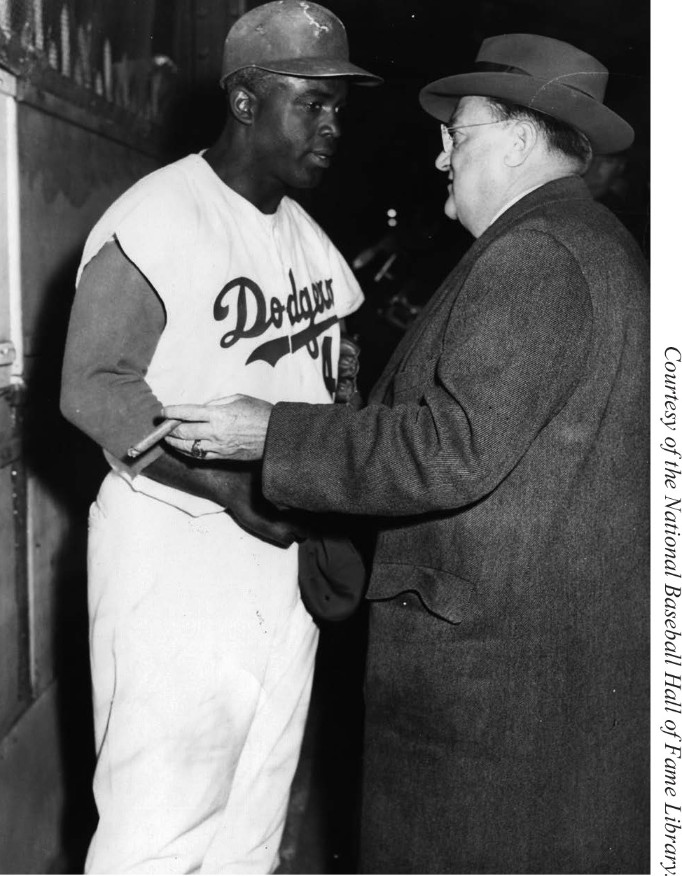

Jackie Robinson and Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley in 1956. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Jack Roosevelt Robinson was not a man to be owned.

Yet, professional baseball’s rules ensured that he would have contractual relations with the owners of the team he played for. And his position as team leader and cultural flashpoint ensured that the relations would be more than purely contractual.

The two owners of Robinson’s team, the Brooklyn Dodgers, were very different men and Robinson had very different relationships with them. One was a mentor and supporter. The other clashed repeatedly with Robinson when Jackie strayed beyond the role of complacent athlete.

Branch Rickey was a vastly complicated man – an innovator, an intellectual in a visceral game, a moralist who knew how to navigate the gray areas of life and baseball’s rules. One of those gray areas was the sport’s attitude toward allowing African-American players into Organized Baseball. Commissioners, such as Kenesaw M. Landis, said it was very possible. The reality was that it did not happen until Rickey’s moral streak and his desire to find the best players and win came together.

The Rickey-Robinson relationship began on a warm day in August 1945. Rickey’s scouts had assured him of the player’s baseball skills. Now Rickey wanted to see if Robinson had the courage and self-control to handle what the first Black player would endure. After three hours of probing, personal questions, and role-playing confrontations, Robinson left the office with the promise of a contract with the Dodgers’ top minor-league club – the Montreal Royals.

Rickey’s support would be steady over the next five years. He helped stifle a clubhouse revolt before Robinson was promoted to the Dodgers in 1947. He stood with him in racist confrontations with the Philadelphia Phillies and St. Louis Cardinals. He insisted Robinson would play in Southern exhibition games, notably in Atlanta in 1949. That season, he freed Robinson from a promise made in that August 1945 meeting. Robinson would no longer have to turn the other cheek.

Robinson’s loyalty to Rickey was strong. “I found myself admiring him, glad to be around him, and ready to do whatever he wanted me to do,” he said in a 1948 autobiography.1

But Branch Rickey also had his patronizing side, a character trait not limited to his relations with African-Americans. In February of 1947, anticipating Robinson’s promotion, he arranged a dinner with prominent Blacks, many of them professionals, at a YMCA in Brooklyn.2 “The one enemy most likely to ruin that success – is the Negro people themselves,” he chided his audience. “You’ll strut. You’ll wear badges. You’ll hold Jackie Robinson Days … and Jackie Robinson Nights. You’ll get drunk. You’ll fight. You’ll be arrested. You’ll wine and dine the player until he is fat and futile. You’ll symbolize his importance into a national comedy.” As Rickey’s assistant Arthur Mann, who was present, wrote, “It was a sharp slap against every Negro face in the room.”3

In 1947, when Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck signed Larry Doby to be the first Black player in the American League, Rickey counseled Veeck to “control the boy.”4 Rickey felt controlling Robinson’s, or Doby’s, reaction to the inevitable racist incidents was necessary to integration’s success. It was at the root of Rickey’s efforts in his first interview with Robinson to take the temperature of his ability to control his temper.

Following Rickey’s advice was not always easy for Robinson. In his rookie season he that was mercilessly race-baited by Philadelphia Phillies manager Ben Chapman. When a backlash ensued, Chapman sought to defuse the situation by asking Robinson to take a picture together. “Having my picture taken with this man was one of the most difficult things I had to make myself do,” Robinson said.5

Regrets also sprouted after Rickey pressured Robinson to testify at a 1949 hearing of the House Un-American Activities Committee. The hearing sprang from singer Paul Robeson’s statement that African-Americans would not go to war to defend a country which had “oppressed us for generations against a country which in one generation has raised our people to the full dignity of mankind.”6 In his testimony, Robinson declined to criticize Robeson directly, but did argue that Blacks would support the US. In later years, he tempered his testimony, saying he stood by it but was much more sympathetic to Robeson and his position.7

These incidents had little impact on the pair’s relationship. “After I left the game, after I had nothing left to offer Mr. Rickey in his business life, he continued to remain close to me, to be concerned about how I was doing,” Robinson said.8 Rickey appeared, and appeared pleased, at Robinson’s induction into baseball’s Hall of Fame.9 “I happen to think Mr. Rickey is a great man with a big heart as well as a big mind. … I shall always speak out with the utmost praise for this man.”10

And that was part of the problem between Robinson and Walter O’Malley. O’Malley and Rickey had been partners owning the Dodgers since 1944. As such, O’Malley could have vetoed the Robinson signing, and did not. In 1950 it became clear that O’Malley and the other partners were not willing to extend Rickey’s generous contract as president and general manager. Rickey decided he had to get out and triggered a clause in their partnership that gave O’Malley the first right to buy him out. O’Malley’s offer was low, and Rickey found an outside buyer whom O’Malley was forced to match – at a much higher level than he wanted. O’Malley was left with control of the team and a resentment at how much it had cost.11 In the early 1950s, Dodgers employees who used Rickey’s name were fined a dollar.12

“I never had any real troubles with the Dodger management until Mr. Rickey left; after that trouble of one kind or another became routine,” Robinson said. “O’Malley had a burning dislike for Rickey people, and I certainly was one.”13

The day-to-day problems revolved around O’Malley’s desire for ballplayers to avoid controversy. Robinson regularly called attention to segregated hotels on Dodgers road trips. To O’Malley, this was the undesirable “causing a scene.”14 When Robinson was notified of a fine for umpire-baiting that he considered unjust, he approached O’Malley, who offered to help if Robinson didn’t say anything to reporters. But Robinson was sitting with a reporter when another Dodgers official approached their table and started discussing the incident. The reporter soon printed the story of the dispute and O’Malley assumed Robinson had violated his promise.15 Roger Kahn reported that O’Malley called Robinson a “shameless publicity seeker.”16

In the end, O’Malley would accuse Robinson of being a “prima donna” for missing spring-training exhibition games because of minor injuries.17 Rae Robinson, Jackie’s wife, exploded at that. “Bringing Jack into Organized Baseball was not the greatest thing Mr. Rickey did for him. In my opinion, it was this: Having brought Jack in, he stuck by him to the very end. He understood Jack. He never listened to the ugly little rumors like those you have mentioned to us today. If there was something wrong, he would go to Jack and ask him about it. He would talk to Jack and they would get to the heart of it like men with a mutual respect for the abilities and feelings of each other.18

In the end, Robinson believed, “O’Malley’s attitude toward me was viciously antagonistic.”19 And, he added, “I was not O’Malley’s kind of Negro.”20

Despite Robinson’s perception, O’Malley was not constantly opposed. He extended the desire to avoid controversy to his own actions. There was a public flap when a woman on a television show asked Robinson if he thought the Yankees, who had no Black players, discriminated. Robinson said yes and O’Malley defended his right to say so.21 When Ford Frick singled out Robinson in the midst of a Giants-Dodgers bean-ball war. O’Malley again publicly rose to Robinson’s defense.22

The contractual relationship ended in further recriminations. After the 1956 season, Robinson decided it was time to retire. He had been approached by the Chock Full o’ Nuts coffee chain and on December 10 agreed to be a vice president. But he was bound by a previous contract with Look magazine, which had bought exclusive rights to the story of his retirement for $50,000. Look, a weekly, couldn’t publish the story until January 8. That delay seemed fine until Buzzie Bavasi, the club’s general manager, called two days after the Chock Full o’ Nuts contract to tell Robinson he’d been traded to the Giants. Because of the Look contract, Robinson felt he couldn’t alert Bavasi to his retirement. The trade story generated anguish among many Dodgers fans. Bavasi and O’Malley were roundly criticized even though the latter had been on a two-month around-the-world cruise until a few days before Bavasi made the trade.

Still feeling bound by the Look contract, Robinson made the appropriate remarks about his anticipation about joining the Giants and let the Dodgers executives take the heat. On January 5, 1957, Look began advertising their story. Then the critical spotlight shifted to Robinson for his refusal to be up-front. Bavasi and Robinson had some cutting remarks to make about each other.23 As for O’Malley, it remained a relationship “of conflict and mutual distrust.”24

When the Urban League of Los Angeles gave O’Malley a plaque honoring his “enlightened leadership” in integration, Robinson called it “preposterous” and gave full credit to Rickey.25 When the NAACP’s Pasadena chapter honored Robinson in 1959, O’Malley pointedly did not attend.26

Robinson’s attitude mellowed somewhat over the years, mostly because Rachel Robinson developed a strong relationship with both O’Malley and his wife.27 In 1964 he told Los Angeles Times columnist Sid Ziff, “It was because of my love and admiration for (Rickey) that I had my difficulty with Mr. O’Malley. That is the only thing that caused the resentment. I’m glad our relations have been ironed out.”28

Despite this resolution, some of the feelings clearly remained. Robinson’s public reconciliation with the Dodgers would have to wait until 1972, when a dying Robinson joined Sandy Koufax and Roy Campanella as the Dodgers retired their uniform numbers, the first time the team had given that honor.29 Significantly, it was not Walter O’Malley, but his son, Peter, who reached out to both Jackie and Rachel and convinced them of the organization’s commitment to racial equality and to repairing their relationship with Robinson.30

ANDY MCCUE is the author of Mover and Shaker: Walter O’Malley, the Dodgers and Baseball’s Westward Expansion, winner of the Seymour Medal as the best book of baseball history or biography for 2014. He is a former president of SABR and a winner of the Bob Davids Award. His next book, Mis-Management 101: Integration, Expansion, and the Growing Irrelevance of the American League, is due out in 2022.

Notes

1 Jackie Robinson, as told to Wendell Smith. Jackie Robinson: My Own Story (New York: Avon Publishers, 1948), 26.

2 Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 416-7.

3 Arthur Mann, The Jackie Robinson Story (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1951), 162-3.

4 Jackie Robinson (Charles Dexter, ed.), Baseball Has Done It (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1964), 58.

5 Jackie Robinson, as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had it Made (New York: G.P. Putnam’s, 1972), 75.

6 Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), 211-6.

7 Robinson and Duckett, 98.

8 Robinson and Duckett, 269.

9 Robinson and Duckett, 270.

10 Carl T. Rowan with Jackie Robinson, Wait Till Next Year: The Life Story of Jackie Robinson (New York: Random House, 1960), 259.

11 Andy McCue, Mover and Shaker: Walter O’Malley, the Dodgers and Baseball’s Westward Expansion (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014), 74-83.

12 McCue, 85.

13 Rowan with Robinson, 256, 259.

14 Sam Lacy, Fighting for Fairness: The Life Story of Hall of Fame Sportswriter Sam Lacy (Centreville, Maryland: Tidewater Publishing, 1998), 121.

15 Rowan with Robinson, 259-60; Robinson and Duckett, 128-9.

16 Los Angeles Times, January 8, 1997.

17 Rowan with Robinson, 257.

18 Robinson and Duckett, 112.

19 Robinson and Duckett, 105.

20 Rowan with Robinson, 261.

21 The Sporting News, December 10, 1952: 3.

22 The Sporting News, May 9, 1951: 2; New York Times, May 2, 3, 1951.

23 McCue, 94-5.

24 Rowan with Robinson, 255.

25 Newark Star-Ledger, May 9, 1958.

26 Los Angeles Times, December 14, 1959.

27 Robinson and Dexter, 160.

28 Los Angeles Times, March 22, 1964.

29 Los Angeles Times, June 5, 1972.

30 The Sporting News, July 1, 1972: 24; The Sporting News’s March 31, 1997, Jackie Robinson Fiftieth Anniversary commemorative section: 2.