Jackie Robinson and Civil Rights: From 1947 Until His Death

This article was written by Leslie Heaphy

This article was published in Jackie Robinson: Perspectives on 42 (2021)

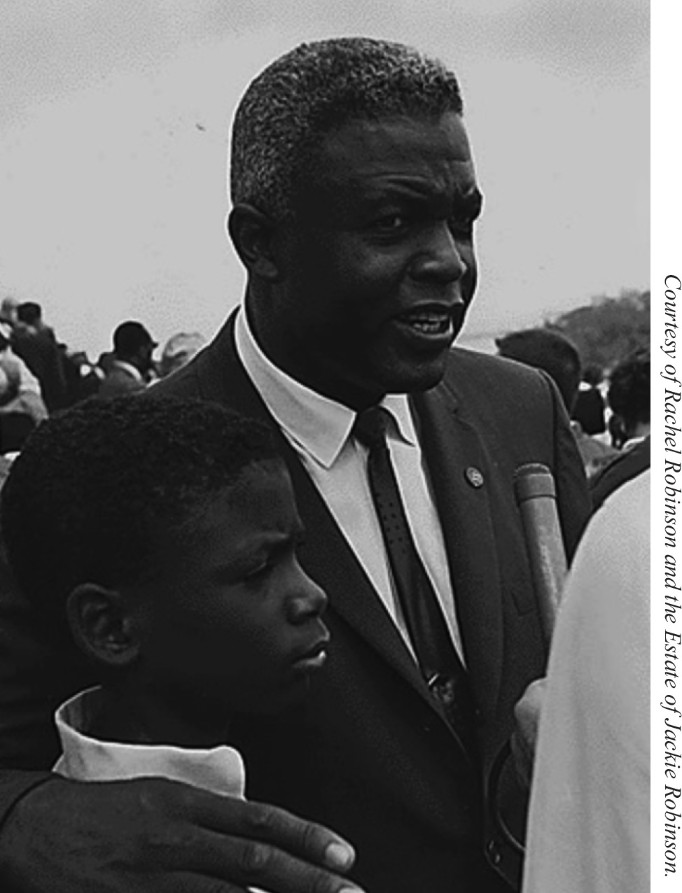

Jackie Robinson speaks to a reporter during the August 28, 1963, Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C.

“I know that you realize that in the tasks that lie ahead all freedom-loving Americans will want to share in achieving a society in which no man is penalized or favored solely because of his race, color, religion or national origin.” – Jackie Robinson1

Historians and sportswriters have presented various views of Jackie Robinson and his civil-rights efforts. Some have characterized him as simply following along, while others have argued that he was much more aggressive than he has been given credit for being. The story of Branch Rickey looking for a player willing to keep quiet and not react to fans’ taunts, insults, and more has contributed to the more passive view. So many books and articles have only examined his baseball achievements and not his off-the-field activities. In more recent years, Michael Long and others have started to explore Robinson’s career after he retired from the Dodgers. Looking at Robinson’s jobs, writings, and personal interactions provide a new look at his importance to the civil-rights movement while he played and after he retired. The picture created is more complicated than simply the passive or aggressive views suggested by others.

Robinson made his debut for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947, and made an immediate impact. Though hitless in the game, he reached on an error and scored the go-ahead run as the Dodgers beat the Boston Braves. Stepping onto the field that long-ago April day thrust Robinson into the spotlight and marked his name in the history books forever. His place was cemented not just as a ballplayer, but also in the history of civil rights. The experiment that Rickey and Robinson started proved to be a success and changed more than the face of baseball; it changed America. Robinson’s play affected the game and the fans in the stands.

Robinson’s success opened the door for others to follow. During his 10-year career, Robinson, rather than marching or protesting, let his play do most of his talking. When he retired after his last game on October 10, 1956, Robinson’s primary efforts shifted from the field to writing, speaking, marching, and working to bring about further changes that would give Blacks in America first-class citizenship. In a speech Robinson gave in June 1964, he acknowledged that he was fortunate enough in life to earn many advantages. But he also said that no Black person had made it in America until even the least privileged Black American had made it.

Every day Robinson took the field, he was making a stand for civil rights, for changing views about what Blacks were able to do. Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, and Ernie Banks are all examples of players whose careers were made possible in part because of Robinson’s career. Though everyone acknowledged that Robinson was not the best player in the Negro Leagues at the time, he was the right choice to integrate and push civil rights forward in America’s national pastime. Buck O’Neil said, “Yet when you look back, what people didn’t realize, and still don’t, was that we got the ball rolling on integration in our whole society.”2 Rickey signing Robinson happened before Brown v. Board of Education and Rosa Parks. Martin Luther King Jr. was still in college as were many other recognized leaders of the movement. Robinson’s position as the first to integrate the White majors in the twentieth century, coupled with his success on the field is only a part of his legacy. His baseball accomplishments made his post-baseball life possible. Robinson used his celebrity status to continue what he started in April 1947. He believed he had a responsibility to use his voice to stand up for change, to fight for rights for all. In his first column for the New York Amsterdam News, in January 1962, Robinson wrote about the obligation he felt to speak out because of who he was.3

Robinson was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee on July 18, 1949, because the committee wanted him to denounce Paul Robeson. He was called to speak out against Robeson for comments attributed to Robeson by the press during a trip to Paris. Robinson went but made some important statements about the voice and role of Black people in America. Robinson began by saying that even if Robeson made comments against the United States, no single Black could speak for all the millions living in America. Robinson declared that Blacks were angry before the Communist Party grew and would continue to be agitated until Jim Crow no longer existed in America. Unfortunately for Robeson, the committee did not really hear what Robinson was saying about American issues with race, but Robinson spoke out clearly on the inequalities that were a part of American history. A few years later, Robeson sent an open letter to Jackie encouraging him to continue speaking out against oppression and wrongs.4

Robinson seemed to live out what Robeson wanted him to do, speak and write against injustices. Robinson became vice president for a major retail industry, wrote for the New York Post and the New York Amsterdam News, served on the board for the NAACP, led fundraising efforts for various civil-rights efforts, and started his own company. He used each of these opportunities to call out racism by his actions and words. In addition, Robinson was also a prolific letter writer, sending hundreds of letters and telegrams to politicians, celebrities, business leaders, and community leaders, challenging them and praising them when he thought that was necessary. While we know today that Robinson used a ghostwriter for some of his columns, his voice is still loud and clear.

After retiring from baseball, Robinson took on the role of vice president for personnel at Chock Full O’ Nuts (1957-1963), becoming the first African American to hold such a position at a large American corporation. Much of his job involved listening to concerns and complaints from employees. For Robinson the job was a chance to encourage and promote Black workers as well as be a role model in the business world. While working for the coffee company, Robinson lent his name to a column appearing in the New York Post that was mostly ghostwritten. He found himself in an early controversy that cost the company some customers after he called out a group of citizens from the Glendale-Ridgewood area of Queens for their “bigotry.” The issue at question was overcrowding of schools. William Black, the head of Chock Full O’ Nuts, came out in support of Robinson, and the company actually gained more customers for that stance.5 He used his position in the company to also send letters to politicians such as President Eisenhower. A May 13, 1958, letter on the company letterhead chastised the president for urging Black Americans to be patient in the face of continued discrimination. These are examples of Robinson’s statements made on numerous occasions that he would not be silent in the face of things he believed to be wrong.6

Robinson also wrote to Richard Nixon in 1957 and thanked him for some of his public remarks, showing early support that would continue for the Republican politician from California. Robinson actually served for a few months in 1960 on Nixon’s election campaign. This support caused some to question Robinson’s commitment to civil rights, but Robinson felt Nixon had a longer record of support than other candidates had. His 1957 letter ended with the following admonition reminding Nixon that the work was far from done. Robinson wrote, “I know that you realize that in the tasks that lie ahead all freedom-loving Americans will want to share in achieving a society in which no man is penalized or favored solely because of his race, color, religion or national origin.”7 Later that same year, Robinson again praised Nixon for his actions aimed at improving the world, focusing on his current actions rather than his record.8

Believing that actions counted most, Robinson withdrew his support for Nixon in the 1968 presidential election. In a January 1969 letter to Nixon, Robinson explained why he and other Black Americans did not support his election. Robinson said, “I must respectfully say I am very much concerned over what I consider a lack of understanding in White America of the desires and ambitions of most Black Americans.” He went on to say that if changes were not made, the confrontations between the two races would get worse. Nixon responded by thanking Robinson for his letter but also asking for his help in healing divisions within the country.9

Robinson wrote continually to politicians and other civic leaders and urged them to do better or challenged them when he disagreed. His letters to John F. Kennedy are a perfect example of this approach. One of his letters to Senator Kennedy in 1959 asked whether Blacks should be happy with what had been accomplished or more focused on what issues still needed to be addressed throughout the country. A February 1961 letter stated, “While I am very happy over your obviously fine start as our President, my concern over Civil Rights and my vigorous opposition to your election is one of sincerity.”10 He hoped that his fears were wrong and that Kennedy would provide the right leadership. Later Kennedy gave a speech on civil rights, and Robinson praised him publicly for his words. Robinson sent Kennedy a telegram thanking him for being a strong leader. Kennedy’s 1963 speech called on America to finally fulfill its original promise to all its citizens. Robinson’s column was published just as news came out about the assassination of Medgar Evers, so he called on people to keep up the pressure, to not give in. He wanted Evers’ death to not have been in vain.11

Robert Kennedy also received much attention from Robinson. Robinson continually called upon the younger Kennedy to not just talk but to act in his role as US attorney general. The former ballplayer said Black America was tired of good words and needed to see real change. This is why he supported Nixon over Kennedy for president, believing Nixon to be the sincerer candidate. Robinson wrote to Robert Kennedy shortly after his brother sent protection for the Freedom Riders in 1961, praising such decisive action and hoping that it would continue.12

Letters and telegrams were also sent regularly to Hubert Humphrey, Barry Goldwater, Lyndon Johnson, and Nelson Rockefeller, calling on them to do more in their political roles. Robinson campaigned for Rockefeller when the New York Republican ran for president in 1964. At the same time, Robinson made clear his dislike of Barry Goldwater’s candidacy. Goldwater responded to some of Robinson’s public criticism in a letter that acknowledged that Robinson’s remarks held more importance than others because of his fame as a former Brooklyn Dodger. People listened to what Robinson wrote and said. Robinson responded to Goldwater’s invitation to meet to talk about civil rights, telling him he thought it was too late and that what Goldwater needed to do was share his views on civil rights publicly and not in private conversations.13

Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and NAACP president Roy Wilkins corresponded with Robinson as well as being frequent topics in some of his news columns. Robinson and King developed a strong friendship through shared goals and beliefs, while Malcolm X and Robinson disagreed on tactics that should be used to bring about change. Wilkins and Robinson had a relationship that waffled between support and criticism. Robinson joined the NAACP board in 1957 believing in their work, but resigned in 1963 after criticizing Wilkins’ leadership and lack of desire to recruit new and younger leaders to the cause.

When King gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963, Robinson and his children were there in support. King called Robinson “… a pilgrim that walked in the lonesome byways toward the high road of Freedom. He was a sit-inner before sit-ins, a freedom rider before freedom rides.”14 At a 1962 Southern Christian Leadership Conference dinner, Robinson praised King as a great man. Following his own words to others, Robinson also acted to help King with his name and his time. He and his wife, Rachel, hosted jazz concerts at their home in Connecticut to help raise bail money to be used for protesters arrested at marches. A June 1963 concert featured the music of Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Billy Taylor, and Dave Brubeck. These concerts eventually became an annual event with the proceeds going to the Jackie Robinson Foundation for scholarships. Upon his election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Robinson donated proceeds from a dinner to honor him to the SCLC voter registration drive. Robinson sent a telegram to President Johnson after Bloody Sunday asking for him to call for an end to the violence before it could get any worse. In October 1958 and April 1959, Robinson and King served together as honorary chairs for the Youth March for Integrated Schools, which was held in Washington.15

King did not escape criticism or challenges from Robinson. In 1960 King received a letter from Robinson questioning some fundraising practices and more importantly asking about supposed comments from SCLC leadership that criticized the NAACP. King assured Robinson in early June that was not something he permitted at any meetings where he was present. He also told Robinson, “I absolutely agree with you that we cannot afford any division at this time and we cannot afford any conflict. And I can assure you that as long as I am President of SCLC, it will not be a party to any development of disunity.”16 Robinson and King realized that any progress toward civil rights would happen more quickly with united voices from the African American community. This was often why so many groups invited Robinson to be present or asked if he would lend his name to their efforts.

In his role as fundraising chair for the NAACP Freedom Fund Campaign beginning in 1957, Robinson traveled all over the country. He visited local chapters to help them in their efforts to raise funds. In January alone, he made trips to nine cities. Robinson’s trips made such an impact that he was invited back to Boston to attend a dinner in his honor. The proceeds from the dinner, hosted by the New England Bowling Association, were donated to the Freedom Fund.17

Invites came regularly for Robinson to speak at all kinds of events, especially those concerning race-related issues. Robinson responded to as many as he could because he felt this was a responsibility that came with the fortune he had in his life. For example, in February 1958 he spoke in Mississippi at a rally for the state’s NAACP branches. The title of his talk was “Patience, Pride and Progress.” Robinson urged those attending to not lose hope but to keep pushing for change and to end discrimination. He gave speeches for a number of Elks organizations over the years, generally focusing on their efforts to give out scholarships to minority students and to help in efforts supporting school desegregation. Robinson also gave suggestions to groups for other speakers who he thought would help them in their civil-rights efforts. One of those suggestions was boxer Floyd Patterson after Patteron took a stand against segregated seating at his fights in Florida.18

Robinson’s work and support of the NAACP was extensive. Not only did he serve on the board and chair various campaigns, he corresponded regularly with Executive Secretary Roy Wilkins. Robinson treated Wilkins as he did all other leaders, both in praise and challenge when he felt the right effort was not happening. When Robinson took a stand over a White restaurant group in Harlem in 1962, Wilkins and the NAACP came out in support of Robinson’s stance. Robinson condemned the anti-Semitic words of a small group of Black protestors chanting outside the steakhouse. Wilkins agreed with Robinson’s column in the New York Amsterdam News and said progress is led by those who treat everyone fairly and not just those like them. Later in 1967 Robinson wrote letters criticizing Wilkins’ leadership of the NAACP, stating he was unhappy with the lack of progress and asking for new membership to move the organization forward. Robinson again said, “I don’t intend to remain silent when I see things I believe to be wrong.”19

While Robinson wrote extensively to public leaders, he also contributed two regular newspaper columns to the New York Post and the Amsterdam News. He was listed as the editor for Our Sports for its five issues in 1953. Robinson was certainly not the writer of many of his columns, but his name was attached and he would not have lent his voice to topics he did not agree with. Alfred Duckett was the likely ghostwriter of his Post columns in 1959 and 1960. Robinson was let go from the Post and had a column in the Amsterdam News from 1962 to 1968. Researcher Raymond McCaffrey studied all 330 News columns that Robinson wrote. He determined that 285 were unique to the Amsterdam News, making them an important resource to understanding Robinson’s full importance to civil rights. Of the articles, 310 dealt specifically with civil rights and 68 with sports and civil rights.20

Robinson used his columns to speak on a range of issues. Sometimes the columns were personal and reflected on his playing days, but most dealt with issues of the day. In 1959, for example, he spoke out about the prejudice within the Boston Red Sox organization. He related how he, Sam Jethroe, and Marvin Williams were invited to a tryout in 1945 and nothing ever came of it. Another 1960 Post article called out a Sports Illustrated writer for an article titled “The Private World of the Negro Ballplayer.” Robinson wrote, “In many respects I found this article unbelievable, insulting and degrading, both to Negro ballplayers and to the intelligence of Sports Illustrated’s readers.”21 Robinson believed the writer was contributing, as many did, to stereotypes about African American athletes. The writer talked about Black ballplayers living in their own world and having their own language, one that no White player could enter. His point was that they had something of their own and did not need the majors, which was not true.22

Speaking about the lack of a Black manager in the major leagues, Robinson challenged Bill Veeck after he became part-owner of the Chicago White Sox. Veeck laid out in an article what he saw as the different characteristics needed for a Black manager to make it. Robinson took Veeck to task for giving in to society and not pushing to hire a Black manager. He wrote, “What is important, however, is the fact that a man like Bill Veeck should find it necessary to retreat from the hard-won standard in baseball today that a man’s abilities are what count, not his color or his ‘temperament’ when it comes to considering a man for management responsibility.”23

As to his possible election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962, Robinson made it clear that he would not beg. He did not want to be elected simply because he was the first Black in the majors but also should not be denied because he spoke out for his own rights and those of others who had no voice. After his election, Robinson wrote about what his selection meant, and said, “These men elected me in spite of the fact that they knew and know now that Jackie Robinson would always say and do only the things in which he believed.”24 A 1963 Amsterdam News column built on this idea as he praised former teammate Roy Campanella for speaking out against discrimination but showed disappointment that Willie Mays and Maury Wills were not more vocal. Again, Robinson felt they all had a duty to use their voices to right wrongs against those to whom no one listened.

Robinson did not limit his columns to chastising baseball for not doing enough. A number of his stories challenged the discriminatory practices of the PGA. When Charlie Sifford was finally allowed to play in PGA tournaments in 1960, he credited Robinson’s columns for helping to get his application accepted. Sifford’s acceptance did not immediately open membership at all clubs to African Americans, just as Robinson’s play with the Dodgers did not throw open the doors of the majors.25

Robinson also wrote about current leaders from Truman to Nixon, apartheid in South Africa, sitins, Black power, the Vietnam War and much more. Robinson supported the US presence in Vietnam and disagreed with King on this issue. He was not a fan of Malcolm X and his calls for all-Black movements and the division he believed was caused by the more militant actions of the Black Muslims and Black Panthers. Robinson believed Malcom X and his followers needed to take responsibility for creating an atmosphere that pushed for division and even, at times, violence. At the same time. Robinson also supported Cassius Clay’s turn to Islam, saying that was the beauty and right of the individual in America. Instead of supporting Malcolm X, Robinson seemed to favor the ideas of Adam Clayton Powell, who described Black Power as people taking charge of their own futures and not relying on others.26

To help create a future for Black Americans that did not rely on White America, Robinson also created a number of businesses. He started his own construction company and bank to give Blacks a position of strength to push for further change. Economic independence would give the Black community a stronger voice. This is why Robinson encouraged people to boycott businesses that did not employ African Americans in their advertisements. He was building off earlier campaigns supported by Newark Eagles owner Effa Manley and others, to not buy where you could not work. In 1970 Robinson and partners created the Jackie Robinson Construction Corporation. Even more significantly, Robinson co-founded the Freedom National Bank in Harlem in 1964. The bank survived until 1990, when it finally closed its doors. From the moment the bank was founded, it struggled against both the White banking industry and even the Black community. The hurdles and expectations were a difficult balancing act, but Robinson believed the good the bank could do outweighed the struggles. After Robinson’s death in 1972, his widow, Rachel, took over the Construction Corporation and continued to build low-income housing. Then, with their children, she created the Jackie Robinson Foundation to continue his legacy by providing educational support to hundreds of students so they could continue their education and build their self-reliance.27

Robinson received a wide array of awards during his lifetime and after his death. Two in particular stand out in recognizing his influence on civil rights in America. In 1956 Robinson became the first athlete to receive the Spingarn Medal, given by the NAACP since 1914. Robinson believed the award showed that his work and efforts transcended the baseball diamond. The second award was the NAACP Annual Merit Award, presented in 1947 to honor his work in integrating baseball.28

Jack Roosevelt Robinson contributed greatly to the civil-rights movement, both on and off the baseball diamond. Much has been written about his integration of America’s national pastime, but far less attention has been paid to his various contributions after he retired. Robinson used his name and position to write to leaders and challenge them to be better. He wrote columns to reach a larger audience and helped raise money for many different causes. He spoke out whenever he saw something he felt was wrong and encouraged others to do the same. Robinson lived with the belief that the work would not finish until every person was treated equally and fairly. One of Robinson’s most often repeated quotes is “A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.”29 Those words truly express what he believed and how he tried to live his life. A final statement from a 1967 Robinson column captures his view of civil-rights activity. “It is the duty and responsibility of each and every one of us to refuse to accept the faintest sign or token of prejudice. It does not matter whether it is directed against us or against others. Racial prejudice is not only a vicious disease, it is contagious.”30

LESLIE HEAPHY is an associate professor of history at Kent State University at Stark. She is the author and/or editor of a number of books, book chapters, and articles on the Negro Leagues, women’s baseball, and the New York Mets. She is currently serving as SABR’s vice president and as a board member for the IWBC (International Women’s Baseball Center).

Notes

1 Letter to Richard Nixon, March 19, 1957, in Michael G. Long, ed., First Class Citizenship: The Civil Rights Letters of Jackie Robinson (New York: Times Books, 2007), 27.

2 Larry Hogan, Shades of Glory, The Negro Leagues and the Story of African American Baseball (Washington: National Geographic, 2006), 377.

3 Raymond McCafrey, “From Baseball Icon to Crusading Columnist,” Journalism History 46:3, 185-207.

4 Eric Nusbaum, “The Story Behind Jackie Robinson’s Moving Testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee, https://time.com/5808543/jackie-robinson-huac/, March 24, 2020; “Negroes Won’t Fight Soviets, Robeson Says,” Washington Post, April 21, 1949: 3; Peter Dreier, “Half a Century before Colin Kaepernick, Jackie Robinson Said, ‘I Cannot Stand and Sing the Anthem,’” The Nation, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/huac-jackie-robinson-paul-robeson/, July 18, 2019; H. Heft, “Jackie Robinson Chides Robeson,” Washington Post, July 19, 1949: 2.

5 Todd Brauckmiller Jr., “Jackie Robinson: An Unexpected Hero of Business and Civil Rights,” STMU History Media, St. Mary’s University of San Antonio, stmuhistorymedia.org/Jackie-robinson.

6 Letter from Jackie Robinson to President Dwight D. Eisenhower; White House Central Files Box 731; File: OF-142-A-3; Dwight D. Eisenhower Library; National Archives and Records Administration, https://www.archives.gov/historical-docs/todays-doc/index.html?dod-date=513.

7 Letter from Jackie Robinson to Richard Nixon, March 4, 1957, BA MSS 102 Series IV Box 1 Folder 5, Jackie Robinson Papers 1934-2001, Library of Congress, copy from Jackie Robinson Papers, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

8 Long, First-Class Citizenship, 38.

9 Long, First-Class Citizenship, 290-292.

10 Long, First-Class Citizenship, 125.

11 Long, First-Class Citizenship, 171-172.

12 Long, First-Class Citizenship, 126, 129.

13 Long, First-Class Citizenship, 198-199.

14 Mike Bertha, “Martin Luther King Jr. and Jackie Robinson: Friends and Civil Rights Icons,” https://www.mlb.com/cut4/mlk-jr-and-jack-ie-robinson-were-good-friends-c162102154, January 18, 2016.

15 Martin B. Cassidy, “Beyond the Dream: Remembering King’s Visit to Stamford,” https://www.stamfordadvocate.com/news/article/Beyond-the-dream-Remembering-King-s-visit-to-4795988.php, September 7, 2013.

16 Letter from Martin Luther King Jr. to Jackie Robinson, June 19, 1960, MLKP-MBU, Martin Luther King Jr. Papers, 1954-1968, Boston University.

17 Tour lists, BA MSS 102 Series IV Box 1 Folder 1, Jackie Robinson Papers 1934-2001, Library of Congress, copy from JR Papers, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

18 Letter to Robinson, January 22, 1958, and Letter to Roy Wilkins, March 15, 1961.

19 Letter from Robinson to Roy Wilkins, February 15, 1967, and Robinson correspondence and columns, BA MSS 102 Series IV Box 1 Folder 3, Jackie Robinson Papers 1934-2001, Library of Congress, copy from JR Papers, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

20 McCafrey.

21 Michael G. Long, ed., Beyond Home Plate: Jackie Robinson on Life after Baseball (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2013), 17.

22 “The Private World of the Negro Ball Player,” Sports Illustrated, March 21, 1960, https://vault.si.com/vault/1960/03/21/the-private-world-of-the-negro-ballplayer.

23 Long, Beyond Home Plate, 21.

24 Long, Beyond Home Plate, 25.

25 Long, Beyond Home Plate, 36-41.

26 Long, Beyond Home Plate, 86-97; Jackie Robinson, “Egg-Throwing and Dr. King,” New York Amsterdam News, July 13, 1963: 11.

27 “Freedom National Bank in Harlem Prepares to Open,” New York Times, December 19, 1964: 37; Roger Wilkins, “Rachel Robinson: the Survivor,” https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/library/magazine/millennium/m5/album-robinson.html; Reggie Wade, “Jackie Robinson Was the ‘Jackie Robinson’ of Banking in Harlem,” https://finance.yahoo.com/news/jackie-robinson-was-the-jackie-robinson-of-banking-in-har-lem-192114397.html, February 20, 2019; “As Black-owned Harlem Bank Dies, So Does a Symbol,” Baltimore Sun, November 14, 1990, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1990-11-14-1990318052-story.html.

28 H.L. Moon, “News from NAACP, Jackie Robinson Named 41st Spingarn Medalist” (New York, June 14, 1956), Reproduced from the Collections of the Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

29 Quotes, https://www.jackierobinson.com/quotes/.

30 New York Amsterdam News, January 28, 1967: 15.