Jackie Robinson and the 1946 International League MVP Award

This article was written by C. Paul Rogers III

This article was published in When Minor League Baseball Almost Went Bust: 1946-1963

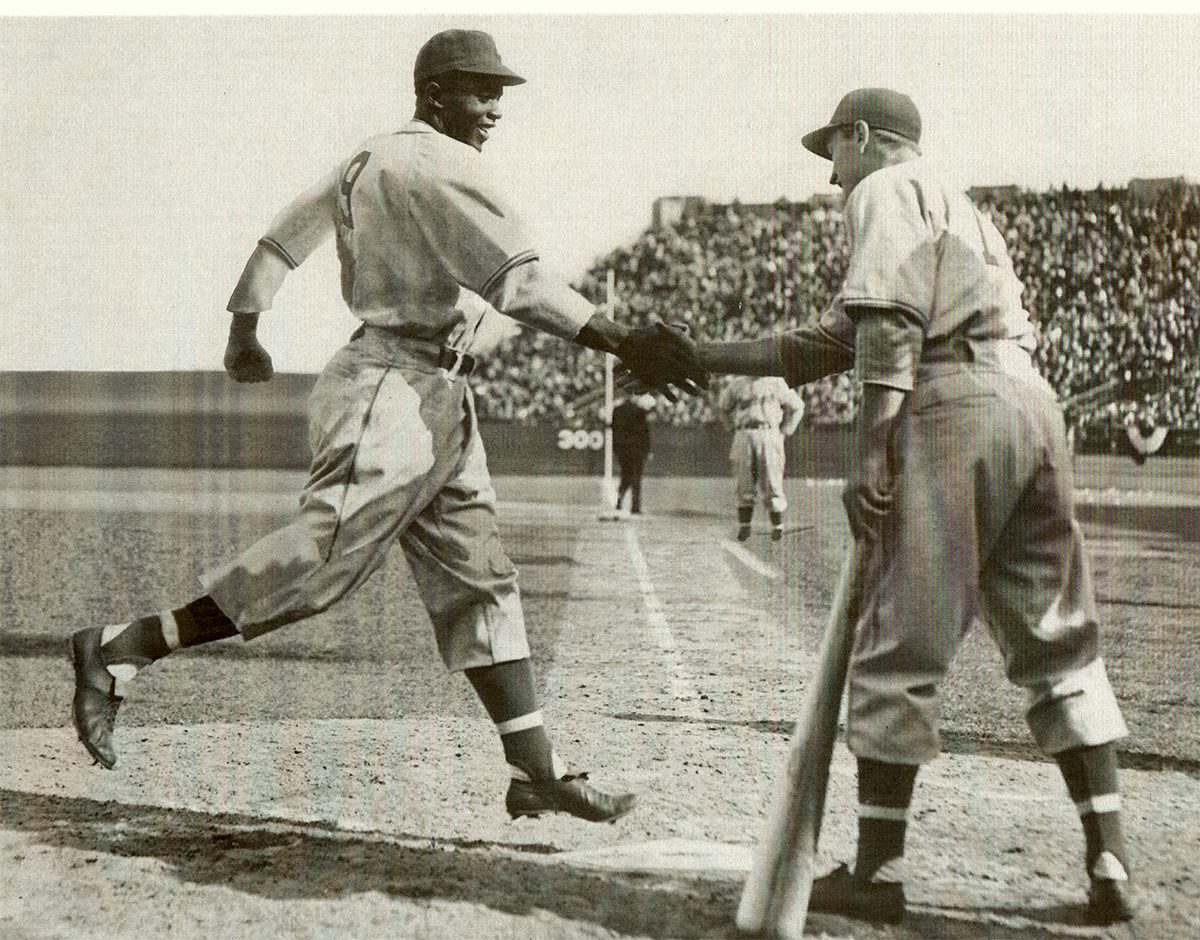

George Shuba greets Jackie Robinson at home plate on April 18, 1946. (Courtesy of Greg Gulas, Carrie Anderson, Mike Shuba)

The 1946 Montreal Royals of the International League have received much attention over the years because Jackie Robinson broke Organized Baseball’s historic and shameful color line by playing second base for the Royals.1 But little consideration has been given to that season’s MVP race, and the fact that Robinson did not win it, even though he had a truly exceptional season for one of the best minor-league teams in baseball history. Indeed, Robinson had such a tremendous season that several writers have incorrectly reported that Jackie did win the league Most Valuable Player Award.2

Those 1946 Royals were a juggernaut, winning 100 of 154 games and sweeping to the International League pennant by 18½ games. They dominated the league playoffs by defeating the fourth-place Newark Bears four games to two in the semifinals before dispatching the second-place Syracuse Chiefs in five games for the league championship. The Royals then defeated the Louisville Colonels, champions of the American Association, in six games to win the Little World Series.

The 27-year-old Jackie Robinson led the Royals, as he batted .349 to lead the league in batting average. Robinson’s slash line was .349/.468/.462/.930 but of course little attention was paid to anything but batting average and, to a lesser extent, slugging average in those days. His 113 runs scored tied for tops in the league and his fielding was superb as he led the league in fielding percentage for second basemen. He stole 40 bases, second in the league only to his teammate, the speedster Marv Rackley. Robinson hit .357 in the league playoffs, “fielding his position spectacular-ly.”3 In the Little World Series against the Louisville Colonels, he remained a force, batting .333 despite constant and virulent racial abuse in Louisville for the three games played there.4

But Robinson did not win the MVP Award or even finish second. The actual results for the league’s MVP voting appear, in hindsight, surprising.5 In the International League Baseball Writers Association voting, Robinson finished in fifth place, behind Eddie Robinson, the slugging first baseman for the Baltimore Orioles; Bobby Brown, the bonus-baby shortstop for the Newark Bears; Jackie’s Montreal teammate Tommy Tatum; and Eddie Joost of Rochester.6 The Sporting News also named Eddie Robinson the league MVP, followed by Brown in second place and Jackie Robinson third.7

THE MVP VOTING

Eddie Robinson was certainly a worthy MVP; he batted .318, smashed 34 home runs, and led the league with 121 RBIs in 143 games.8 Bobby Brown, dubbed the “Golden Boy” by the press,9 also had an impressive season in his first year in professional baseball, batting .341, second in the league behind Jackie Robinson, and tying for the most hits in the circuit with 174.10 Jackie’s Montreal teammate Tommy Tatum who finished third in the writers’ voting, batted .319 and was a jack-of-all-trades who played six different positions for the Royals.11

The obvious question is: How could Jackie Robinson have finished third and fifth in the voting for the two International League MVP Awards given his performance in 1946, which one writer has asserted was “perhaps the best single season of any player ever in the International League”?12 In the voting by the writers, Eddie Robinson was the runaway winner with 250 points. Second-place Brown had 135 points, followed closely by Tatum with 127 points, Joost with 120 points, and Jackie Robinson, in fifth place with 89 points.13 Thus, according to the writers, Robinson was not even the most valuable player on his own team.

The voting for The Sporting News version of the MVP was conducted by its eight league correspondents, one for each International League entry.14 That voting was tighter, with Eddie Robinson finishing on top with 51 votes, including three first-place votes, three seconds, and one third. Bobby Brown’s runner-up total was 42 points, including one first-place vote, while Jackie Robinson finished with 30 points and two first-place votes.15

Although Branch Rickey’s signing of Jackie Robinson and his season with the Royals have been well-documented,16 the paths to the International League and beyond of the other MVP candidates have not and provide interesting context to the 1946 MVP race. While Tatum’s subsequent big-league career was limited, both Eddie Robinson and Bobby Brown, who was in medical school at Tulane, had substantial major-league careers. Their routes to the International League, however, and then on to the major leagues differed significantly.

EDDIE ROBINSON

Eddie Robinson, from Paris, Texas, was 25 years old in 1946 and returning from three years of service in the Navy. While stationed in Hawaii he had undergone surgery to remove a bone tumor in his leg. The Navy surgeon, however, inadvertently damaged the peroneal nerve, which controls one’s ability to lift one’s foot. The damaged nerve threatened Robinson’s baseball career and necessitated a second operation by a specialist in Bethesda, Maryland, to repair the damage and enable the nerve to grow back.

Robinson had appeared in eight games for the Cleveland Indians at the end of the 1942 season before joining the military and upon his discharge from the Navy reported to the Indians’ 1946 spring training in Clearwater, Florida. When he reported he still had a brace on his leg and was not sure that his damaged leg would allow him to play. But the nerve had regenerated and grown over the previous six months, alleviating his drop foot and enabling him to discard the brace on the first day.17

After his long layoff from baseball, Robinson did not hit much during spring training, prompting the Indians to award the first-base job to Les Fleming and send Eddie to Baltimore so that he could play every day. But more hardship awaited Eddie when the season began. His daughter Robby Ann, who was born in late 1943, became seriously ill and was hospitalized at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore with an inoperable brain tumor. She lapsed into a coma while in intensive care and died before her third birthday. Eddie was understandably grief-stricken and missed several games before returning to the Orioles lineup.18

One of the highlights of Robinson’s 1946 season came against the Newark Bears in a game in Baltimore. The Orioles played their games in Baltimore Stadium, which was a football stadium, since Oriole Park, the team’s baseball park, had burned down during the 1944 season.19 The baseball field was configured like the Los Angeles Coliseum later was when the Dodgers moved to the West Coast, with a high fence at a very short left field and no fence at all in right, just the other end of the football field. Thus, the only way to hit a home run to straightaway right field was to run around the bases while the ball was in play.

As Bobby Brown remembered years later, Eddie Robinson hit a ball about 40 feet over the head of Bears right fielder Hal Douglas. The ball rolled all the way to the steps of a temporary clubhouse in deep, deep right field. Robinson was always a slow runner, made even slower due to his damaged leg, but he circled the bases and was sitting in the dugout by the time Douglas retrieved the ball.20

Led by Robinson and Howie Moss, who hit 38 homers and drove in 112 runs,21 the Orioles finished in a tie for third place in 1946 with an 80-73 record, 19 games behind Montreal, before losing to the second-place Syracuse Chiefs in six games in the first round of the playoffs.22

Robinson became the regular first baseman for the Cleveland Indians in 1947 until mid-August, when he fouled a pitch by Allie Reynolds off his ankle and fractured a bone, sidelining him for the season.23 But he was back at first for the Indians’ magical run to the pennant and World Series championship in 1948, batting .300 in the Series.

Robinson went on to play 13 big-league seasons with seven American League teams, making four All-Star teams, and playing in another World Series with the 1955 New York Yankees.24 After his playing career, he successfully made the transition to the front office, eventually serving as general manager of the Atlanta Braves and of the Texas Rangers.

BOBBY BROWN

The 21-year-old Bobby Brown also had a unique path to the International League, straight from the Tulane Medical School, where, as he put it, he was “the best hitter in his medical school class.”25 He had begun his collegiate career at Stanford but enlisted in the Navy’s wartime V12 program as a pre-med student when he turned 18. During his freshman year at Stanford, he hit .405 for the varsity26 and caught the eye of Ty Cobb, who sometimes attended Stanford games. When Brown was called to active duty on July 1, 1943, the Navy sent him to UCLA to finish his pre-med studies. Brown played on the UCLA Bruins baseball team, where Jackie Robinson had starred a few years earlier, during his year there and batted close to .500.

With his pre-med studies complete, the Navy sent Brown to Tulane for medical school. There, seemingly against all odds, he managed to play for Tulane’s baseball team during his first year in med school, again batting over .450.27 Thus, due to the vagaries caused by World War II, Brown played and starred for three universities in three years.28 He was later elected to the Sports Halls of Fame for all three schools.

With the war over, Brown was discharged from the Navy in January 1946. The Yankees then outbid several other teams and signed him to a record $52,000 bonus that spring while he was in his second year of medical school. The Tulane administration, after much deliberation, agreed to allow Brown to continue in medical school even after he signed a professional baseball contract.29

After signing, Brown reported to Yankees spring training in St. Petersburg, Florida, where the manager was Joe McCarthy. The 1946 camp was a very large one with all the war veteran players returning to baseball. Brown played exceptionally well, with one highlight a grand slam against the Norfolk minor-league outfit.

Near the end of camp, Yankees general manager George Weiss told Brown that he was going to start the season with the Binghamton (New York) Triplets of the Double-A Eastern League. Brown balked, however, and said he wanted to start at a higher classification and that he would not report to the Triplets. Weiss relented and said, “Okay, we will send you to Newark.”30

Brown knew that breaking in directly with the Yankees infield would be difficult, since they had Phil Rizzuto at shortstop, George Stirnweiss, who had won the 1945 American League batting title, at second, and Billy Johnson, who was returning from the service after a strong rookie year in 1943, at third base. Brown also had worked out in the Newark ballpark when he was 14 years old and living in New Jersey, and so was familiar with the surroundings.

Brown appeared in 148 games, all but a handful at shortstop, for the 1946 Bears while no other player played in more than 117 games for Newark. At the end of the International League campaign, the Yankees sent a late-season call for Brown, along with Yogi Berra, pitcher Vic Raschi, and outfielder Frank Colman. With New York, Brown batted .333 in eight games and 29 plate appearances.31 His minor-league days, like those of the two Robinsons, were at an end.

Brown continued to both attend medical school and play for the Yankees until he graduated in April 1950. He typically was not able to go to spring training and in at least two seasons showed up from Tulane on Opening Day. He showed his ability to come through in the clutch in the four World Series he played in with the Yankees, batting a cumulative .439 in 41 at-bats with five doubles, three triples, and nine runs batted in.

After the Korean Conflict broke out in 1950, the military began seeking doctors from the old V12 program who had gone to medical school during World War II but had not been deployed. Early in 1952, the now Dr. Brown was told that he had to reenlist as a medical officer or that he would be drafted as a private. He chose the Army, which required a two-year commitment, and on July 1, 1952, he reported to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, thus ending his season with the Yankees prematurely.

Brown was then deployed to Korea and arrived there on October 1, 1952, the day his Yankees opened the World Series against the Brooklyn Dodgers. He served in a MASH unit and with a field artillery battalion for 10 months before being transferred to the US military hospital in Tokyo for the rest of his deployment.32

Dr. Brown was honorably discharged in April 1954, having missed more than half of the 1952 and all of the 1953 seasons. He had an internal medicine residency lined up to begin July 1, 1954, at Stanford but was able to play for the Yankees for a couple of months, appearing in 29 games. Then on June 30, Brown played his last major-league game, manning third base and going 2-for-4 against Willard Nixon in a 6-1 Yankees loss to the Boston Red Sox in Fenway Park.33 After the game he boarded a red-eye flight to San Francisco so he could begin his residency on July 1.34 At 29 years of age, Brown walked away from baseball to pursue his medical career.

After his three-year residency program at Stanford, Brown returned to Tulane for a one-year cardiology fellowship. He then practiced cardiology for 25 years in Fort Worth before major-league baseball came calling again; he was named president of the American League, an office he filled from 1984 to 1994.35 Later Dr. Brown’s only regret would be that as a player he was not able to go to spring training and give baseball his undivided attention for a few years. But he had no regrets about becoming a doctor and practicing medicine.36

TOMMY TATUM

As mentioned, Tommy Tatum, who finished third in the writers’ voting for MVP, had a stellar year for Montreal in 1946. After growing up in Oklahoma City, he broke into professional baseball in 1938 at 18 and had an eight-game cup of coffee with the Dodgers in 1941. In 1946 he was coming off three years in the US Army Signal Corps and, at 26, had one of the best seasons of his 15-year playing career. In addition to his .319 batting average, he stole 28 bases and made the International League All-Star team. Tatum made the Dodgers roster out of spring training in 1947 but ran into a very crowded Brooklyn outfield. After appearing in just six games for the Dodgers, mostly as a pinch-hitter, he was sold to the Cincinnati Reds on May 13. With the Reds he hit .273 in 69 games in his major-league swan song before returning to the minor leagues. He served as player-manager for the Oklahoma City Indians in the Texas League from 1951 through 1955 before retiring from baseball.

In his brief time with the 1947 Dodgers, Tatum did have a moment important for the annals of baseball history. On April 18 he had his only start for Brooklyn, batting third between Jackie Robinson, who was second in the lineup, and Dixie Walker against the New York Giants in the Polo Grounds. In the top of the third inning, Robinson led off with a home run to deep left field off Dave Koslo and was greeted with outstretched arms at home plate by Tatum. A photo taken at that moment captured the racial integration of the major leagues and was published in newspapers throughout the country. 37

JACKIE ROBINSON

In his first year with the Brooklyn Dodgers, 1947, Jackie Robinson faced a torrent of racism and vitriol.38 He somehow persevered as he batted .297 while playing first base, another new position, helping lead Brooklyn to the pennant. He went on to a storied 10year Hall of Fame career for the Dodgers, who won six pennants and one World Series championship during his tenure.

Robinson’s difficult rookie year with the Dodgers has rightfully received much attention.39 However, Robinson’s first major challenge, with his wife, Rachel, by his side, was to survive a month of spring training in 1946 with the Montreal Royals in the Jim Crow South.40 The Royals were supposed to train in Sanford, Florida, but were forced to move their camp to Daytona Beach, near the parent Dodgers, because of threatened mob violence in Sanford.41 The Royals also had to cancel games in Jacksonville, where the local authorities padlocked the field,42 and Deland because of local segregation laws forbidding Whites from playing against Blacks.43

Robinson and fellow African American Johnny Wright were also subject to constant racial abuse when the Royals did play spring-training games. Robinson, who had relatively little baseball-playing experience,44 struggled hitting against the curveball. He was also troubled by a sore arm,45 necessitating a shift from shortstop, his former position, to second base.46

He also faced challenges from the opposition, such as the time in an exhibition game against Indianapolis when veteran pitcher Paul Derringer knocked Robinson down not once, but twice. Robinson then smashed the next pitch past third for a hit. Later in the game, Derringer again threw at Robinson’s head. This time Robinson retaliated by smashing a triple to deep left field.47

Robinson’s less-than-stellar spring training created some skepticism in Montreal about the impact he would have on the playing field. Some believed that the much more experienced Johnny Wright was the more likely of the two to eventually crack the Brooklyn Dodgers lineup.48

It didn’t take long for Robinson to dispel that doubt as he had a spectacular debut on April 18 against the Jersey City Giants in their Roosevelt Stadium. After grounding out to shortstop in his first at-bat, Robinson came up again in the third inning with two men on base and nobody out. He smashed the first pitch from Jersey City’s Warren Sandel over the left-field fence for a three-run home run.49 He finished a memorable first game with four hits, two on bunts, three RBIs, and two stolen bases. For the day he also scored four runs, two improbably on balks he induced when dancing off third base.50 The Royals won 14-1 to start the season with a bang. By the time of the Royals’ home opener two weeks later, Robinson was hitting .362 with no sign of slowing down.

The season was not without its travails, however. Robinson missed some games in June with a leg issue. Later in the summer when he slumped and grew visibly tired and listless, a doctor ordered him to take 10 days off to relax and recharge his batteries. He did spend four days away from the team and the respite did indeed help get him back on track.51

For the most part, Robinson was treated well by the fans at home and away. The Montreal fans loved him, but he did encounter some racial taunting during his first trip to Baltimore.52 Also, Syracuse Chiefs fans and players hurled invective at him early in the season.53

The worst treatment, however, occurred in Louisville in the Little World Series, which pitted the champions of the International League against the champions of the American Association, the Louisville Colonels. The first three games of the series were in Louisville and the verbal barrage from the fans there was abusive and constant. Robinson was only 1-for-10 as Louisville won two of the three games.

When the series moved to Montreal, the Royals fans showed their displeasure with the way Louisville had treated Robinson and, starting with leadoff man Johnny Welaj, booed every move a Colonels player made.54 Once before hometown fans, Robinson quickly regained his form, driving in the winning run in the 10th inning of game four with a two-out line single to left. In the fifth game, he doubled, tripled, and had a key bunt single to drive in the decisive run, while in the final game he had two more hits and made several key plays in the field as the Royals beat Louisville 2-0 to wrap up the series.55

Robinson was 7-for-14 in the three games in Montreal and afterward was carried around the field by the jubilant fans, who chanted in French “[H]e has earned his stripes.”56 When he left the ballpark in his street clothes to rush to the airport to fly to Detroit, where he was to begin a barnstorming tour, he was again mobbed by thousands of fans, leading to the famous line about a White mob chasing a Black man out of love and not hatred.57

Robinson would describe the people of Montreal generally as being “warm and wonderful” to Rachel and himself. In fact, the citizenry was so attentive to them as a couple that he felt they had little privacy. But he would remember his time in Montreal with real fondness.58

Although Robinson was under intense scrutiny when he broke into the National League in 1947 with the Dodgers, he also played under tremendous pressure in 1946 with Montreal. It is difficult to underestimate the attention he drew. Robin Roberts, who was pitching in the semipro Northern League in Vermont that summer, remembered driving up to Montreal on an offday with a couple of teammates just to watch Robinson play. He came away very impressed; Robinson went 3-for-4 with a steal of home and played errorless ball at second base.59

Although Jackie Robinson did not win the International League MVP in 1946, he was named the National League Rookie of the Year the next year when he broke major-league baseball’s unofficial color ban. In 1949 the 30-year-old Robinson led the National League in hitting with a .342 average and was named Most Valuable Player by the baseball writers, outdistancing Stan Musial 264 points to 226.60

AN ANALYSIS OF THE VOTING

The question remains, however, whether the voting for the 1946 International League Most Valuable Player Awards was racially biased. Viewed in hindsight over three-quarters of a century later, it is difficult to know for certain, but one cannot help but be suspicious.

Although it is unclear if the voting was based only on the regular season and not the playoffs,61 either way Jackie Robinson’s performance was exceptional. At a minimum, Robinson was the best player on the best team in the league, indeed on one of the best teams in minor-league history. But Eddie Robinson and Bobby Brown also had outstanding years for first-division ballclubs. Certainly, actual MVP Eddie Robinson had the best combination of power and average, resulting in a .983 OPS, second to Montreal’s Lew Riggs, who appeared in only 90 games, and considerably better than Jackie’s OPS of .930. Of the statistics that were considered paramount at the time, Eddie’s 123 runs batted in, which led the league by a wide margin, coupled with his 34 home runs, certainly would have attracted widespread attention. His .578 slugging percentage, well above Jackie’s .462, also led the league and would have been considered a major plus factor. Thus, Eddie was most deserving of the MVP.

Bobby Brown, who finished second in the MVP voting with 135 points to Jackie Robinson’s 89-point total, had in many ways similar statistics to Jackie. Brown was second in hitting at .341 to Jackie’s .349 and neither hit many home runs.62 Robinson’s .930 OPS was higher than Brown’s .870. Both were very difficult to strike out; Robinson fanned 27 times in 553 plate appearances while Brown was even tougher, with only 19 punchouts in 597 times at the plate.63 And most impressively, both were playing their first seasons in Organized Baseball.

It is also worth noting that Jackie Robinson did not mention the International League MVP Award in either of his two autobiographies.64 Perhaps there is no reason that he should have, given that he did not win. However, he might well have mentioned it if he felt that he had been the victim of racial prejudice.65 He was certainly not shy about later alluding to the racial injustices that confronted him.

The fact, however, that Jackie finished fifth in the voting by the sportswriters, well behind Eddie Joost, strongly smacks of discrimination. The 30-year-old Joost, who spent 17 years in the big leagues, had a fine year as the shortstop for the seventh-place Rochester Red Wings, with 19 home runs and 101 runs batted in. He batted a pedestrian .276, however—73 points below Robinson—and did not come close to leading the league in any category. Yet he polled 120 points in the voting by the writers, well ahead of Jackie Robinson’s 89-point total.

CONCLUSION

Thus, there is certainly circumstantial evidence of bias in that long-ago MVP voting. If we just look at the first-place votes in the writers’ poll, Eddie Robinson received 16 of them, followed by Tommy Tatum with 10. Jackie Robinson garnered seven top votes while Jack Wallaesa of Toronto had the other.66 While the author could not locate the votes of the individual sportswriters, it is likely that some left Jackie off their ballots entirely, considering that even with seven first-place votes, his 89-point total was far behind the four in front of him.

Both Jackie and Eddie Robinson overcame significant obstacles to get to the International League and endured a great deal of hardship in 1946, albeit of a very different nature. Whether the absence of prejudice in the MVP voting would have swapped them and made Jackie the winner is unlikely given Eddie’s power numbers and .318 batting average. But it would certainly have made for a closer race and would have bumped Jackie Robinson well up from fifth place. How far up, we will never know.

C. PAUL ROGERS III is co-author or co-editor of several baseball books including The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant Race (Temple University Press, 1996) with boyhood hero Robin Roberts and Lucky Me: My 65 Years in Baseball (SMU Press, 2011) with Eddie Robinson. Paul is president of the Ernie Banks-Bobby Bragan DFW Chapter of SABR and a frequent contributor to the SABR BioProject, but his real job is as a law professor at the SMU Dedman School of Law, where he served as dean for nine years. He has also served as SMU’s faculty athletic representative for 37 years and counting.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article was edited by David Siegel and fact-checked by Laura Peebles.

NOTES

1 Jack Anderson, “A Great Leap Forward: Jackie Robinsson and the View from Montreal,” https://sabr.org/journal/article/a-great-leap-forward-jackie-robinson-and-the-view-from-montreal/.

2 Scott Simon, Jackie Robinson and the Integration of Baseball (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2002), 97; David Falkner, Great Time Coming: The Life of Jackie Robinson from Baseball to Birmingham (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 138; Tommy Holmes, Dodger Daze and Knights (New York: David McKay Company, Inc., 1953), 200.

3 “Robinson’s Bidding for Berths in Baseball Majors Next Spring,” Eau Claire (Wisconsin) Leader-Telegram, October 23, 1946: 10.

4 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 141-42; Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), 156-157; Maury Allen, Jackie Robinson: A Life Remembered (New York: Franklin Watts, 1987), 83.

5 According to one historian, at the time some believed Jackie Robinson should have received the MVP Award. Bill O’Neal, The International League: A Baseball History 1884-1991 (Austin, Texas: Eakin Press, 1992), 141.

6 “Robinson Most Valuable in International Loop,” Elmira (New York) StarGazette, October 17, 1946: 27.

7 “Robinson Third Oriole Honored in as Many Years,” The Sporting News, October 16, 1946: 13.

8 Eddie Robinson was the third Baltimore Oriole in a row to win the International League MVP, following Howie Moss in 1944 and Sherm Lollar in 1945. The streak was broken in 1947 when Hank Sauer of Syracuse won the award.

9 Tom Meany, The Magnificent Yankees (New York: A.S Barnes & Company, 1952), 153; Arthur Daley, “Baseball’s Golden Boy: Bobby Brown Keeps his Medical Career in Mind as He Hits Away for the Yanks,” Sportfolio Magazine, October 1948: 49.

10 Danny Murtaugh, future manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates World Series winner in 1960, also had 174 hits for the Rochester Red Wings.

11 “Eddie Robinson International League V-Man, Montreal Star, October 5, 1946: 24.

12 Simon, 97.

13 “Robinson of Baltimore Named Most Valuable Man,” North Bay (Ontario) Nugget, October 5, 1946:21.

14 “Robinson Third Oriole Honored in as Many Years,” The Sporting News, October 16, 1946: 13. It is quite likely that those eight scribes also voted in the writers’ balloting.

15 Montreal’s Tatum and Baltimore’s John Podgajny also received single first-place votes. Larry Berra of Newark, not yet referred to as Yogi by the baseball world, was far down the list with six total points. The Sporting News, October 16, 1946: 13. Berra had hit .314 in 77 games before his late season call-up to the Yankees.

16 Tygiel; Rampersad; Falkner.

17 Eddie Robinson with C. Paul Rogers III, Lucky Me — My Sixty-Five Years in Baseball (Dallas: SMU Press, 2011), 31-35.

18 Robinson with Rogers, 28-29.

19 O’Neal, 142.

20 Robinson with Rogers, xv.

21 After failed trials with the Indians and Cincinnati Reds late in 1946, the right-handed Moss returned to Baltimore for the 1947 season and took full advantage of the short-left field porch, smacking 53 homers to again lead the league. In all, “Howitzer Howie” led the International League in home runs four times, the only person in the history of the league to do so. O’Neal, 243. But in 76 major-league plate appearances over parts of three seasons, Moss failed to hit a home run, recorded no extra-base hits, and drove in only a single run.

22 The Orioles actually finished the regular season tied with the Newark Bears for third place, one game behind the second-place Chiefs. Baltimore then defeated Newark in a one-game playoff for third place, with the loser having to face first-place Montreal in the first round of the league playoffs.

23 Robinson with Rogers, 42.

24 Within months of his retirement as a player in 1957, Robinson’s foot-drop issue recurred, an issue he dealt with the rest of his life. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Eddie-Robinson/.

25 William Clifford Roberts, MD, “Robert William (“Bobby”) Brown, MD, Cardiologist, Major League Baseball Player (New York Yankee) and American League President: A Conversation with the Editor,” American Journal of Cardiology (2008): 725.

26 Daley, 54.

27 According to Dr. Brown, if Tulane had an away game, typically against a service team, the Tulane team bus would wait for him outside his afternoon lab or class, and then leave. For home games, the Tulane coach would tell the opposition that “we can’t start the game until the shortstop arrives and he is in med school.” C. Paul Rogers III, “Wartime Baseball, Medicine, and the New York Yankees: A Conversation with Dr. Bobby Brown,” Elysian Fields Quarterly (vol. 16, no. 3, 1999): 62-63.

28 “Wartime Baseball, Medicine, and the New York Yankees: A Conversation with Dr. Bobby Brown,” Elysian Fields Quarterly (vol. 16, no. 3, 1999): 60-61.

29 Roberts, 725.

30 Roberts, 726.

31 In contrast, Yogi Berra batted .364 in 23 plate appearances.

32 Roberts, 733-734.

33 Eddie Robinson was Brown’s teammate with the Yankees in 1954 and appeared as a pinch-hitter in Brown’s last game.

34 Dr. Brown reported to the San Francisco County Hospital (which was part of the Stanford residency program) around noon on July I. According to Brown, “They said report July I. They didn’t say what time.” Rogers, 73.

35 Dr. Brown took a six-month hiatus from his practice in 1974 to serve as interim president of the Texas Rangers after Brad Corbett bought the team. Rogers, 74.

36 Rogers, 75.

37 https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Tommy-Tatum/.

38 Robin Roberts and C. Paul Rogers III, The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), 48-52.

39 Red Barber, 1947 — When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball (New York: Doubleday & Co., 1982).

40 Chris Lamb, Blackout: The Untold Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Spring Training (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004),

41 Lamb, 83-90; William Brown, Baseball’s Fabulous Montreal Royals (Montreal: Robert Davies Publishing, 1996), 97.

42 Jackie Robinson as told to Wendell Smith, Jackie Robinson — My Own Story (New York: Greenberg Publishers, 1948), 79; Lamb, 135-136.

43 Kostya Kennedy, True—The Four Seasons of Jackie Robinson (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2022), 22.; Lamb, 140-141.

44 Robinson had played relatively few games at Pasadena Junior College and UCLA, where baseball was perhaps his fourth best sport while in college, had played 34 games with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League in 1945 and barnstormed in Venezuela briefly after that season. James W. Johnson, The Black Brums: The Remarkable Lives of UCLA’s Jackie Robinson, Woody Strode, Tom Bradley, Kenny Washington, and Ray Bartlett (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 56, 60, 103.

45 Lamb, 94-95.

46 Teammate Lou Rochelli, whose was also in line for the second base job, helped Robinson transition to second and taught him how to turn the double play, a gesture Robinson never forgot. Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made: An Autobiography (New York: Putnam, 1972), 44.

47 Kennedy, 17; Brown, 99.

48 This was especially true because the Dodgers were short on pitching but had Pee Wee Reese at shortstop and Eddie Stanky at second base, both front-line major leaguers. Kennedy, 29-30.

49 In two significant actions of acceptance, manager Clay Hopper, who was from Mississippi and was coaching third, slapped Robinson on the back as he crossed third base and the next batter, George Shuba, shook Robinson’s hand as he crossed the plate. Brown, 101-102; Kennedy, 32. George “Shotgun” Shuba, as told to Greg Gulas, My Memories as a Brooklyn Dodger (Youngstown, Ohio: City Printing Company, 2007), 32-34.

50 Kennedy, 32-33.

51 Robinson as told to Smith, Jackie Robinson — My Own Story, 105.

52 Robinson, I Never Had It Made, 46.

53 Robinson as told to Smith, Jackie Robinson — My Own Story, 106; Robinson, I Never Had It Made, 49.

54 Kennedy, 57.

55 Mark J. Steiner, “Jackie Robinson: History Made at the 1946 Junior World Series.” https://sabr.org/journal/article/jackie-robinson-history-made-at-the-1946-junior-world-series/

56 Tygiel, 143.

57 Brown, 111-112; Anderson; Steiner.

58 Robinson, I Never Had it Made, 47.

59 Roberts and Rogers, 48. Of course, Roberts would later become the ace of the Philadelphia Phillies and face Jackie Robinson many times in the National League, including his defeat of the Dodgers on the last day of the season in 1950 to clinch the pennant for the Whiz Kids.

60 Robinson received 12 of 24 first-place votes while Musial received 5.

61 The results of the sportswriters’ poll was announced at the sixth game of the Little World Series between Montreal and Louisville, after the International League playoffs had concluded. “Oriole’ First Sacker Voted Most Valuable,” Sault Star (Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, Canada), October 5, 1946: 13.

62 Brown hit five home runs while Robinson hit only three, including the three-run shot on Opening Day. But both were among the league leaders in doubles with 27 and 25 respectively.

63 Eddie Robinson was also very difficult to strike out, especially considering he was a power hitter. In 1946 he struck out only 47 times in 607 plate appearances.

64 Robinson, I Never Had It Made, Robinson as told to Smith, Jackie Robinson —My Own Story.

65 Rachel Robinson also did not allude to the 1946 MVP voting in her memoir about her life with Jackie. Rachel Robinson with Lee Daniels, Jackie Robinson — An Intimate Portrait (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1996).

66 The first-place vote for Wallaesa was indeed puzzling as he split the season between Toronto and the Philadelphia Athletics, batting .253 in 63 games for the sixth-place Maple Leafs.