Jackie Robinson and the Kansas City Call

This article was written by William A. Young

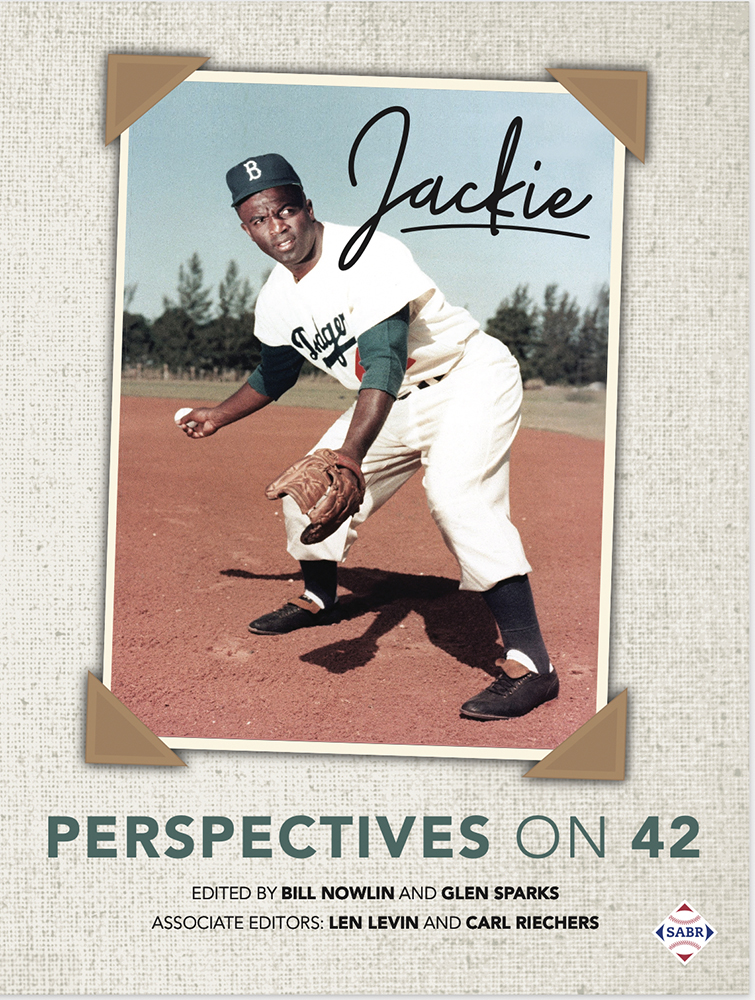

This article was published in Jackie Robinson: Perspectives on 42 (2021)

By the spring of 1945, Jackie Robinson was well known to readers of the Kansas City Call, the Black-owned and -operated weekly newspaper that had covered the Kansas City Monarchs thoroughly since the team’s origin in 1920. The Call had reported on Robinson’s exploits as a UCLA football star,1 and even his winning a ping-pong tournament while he was in the US Army stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas.2

By the spring of 1945, Jackie Robinson was well known to readers of the Kansas City Call, the Black-owned and -operated weekly newspaper that had covered the Kansas City Monarchs thoroughly since the team’s origin in 1920. The Call had reported on Robinson’s exploits as a UCLA football star,1 and even his winning a ping-pong tournament while he was in the US Army stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas.2

Robinson’s joining the Monarchs was reported in the March 2, 1945, edition of the Call, with the headline “Monarchs Add Jackie Robinson. All-American Footballer Joins Club.” The article read in full: “Leading the list of well-known players added to the Monarch roster for the coming season is none other than Jackie Robinson, nationally known letterman at the University of California at Los Angeles and former lieutenant in the army. Although Robinson is better known as an All-American football player out California way, his prowess as a baseball player is known by several clubs in both leagues. Robinson has recently received a medical discharge from the army and decided to cast his lot with the Monarchs. He is present coach at Sam Huston college in Austin, Texas. He will play in the infield in the Monarch lineup.”

Two weeks later, the Call had this to say about the rookie: “The ‘prize freshman’ at the Monarchs training camp [in Houston] will be Jackie Robinson, who most likely will not report until the first week of April. He has to finish up his responsibilities at Sam Houston [sic] college where he is a coach.”3

The first mention in the Call of Robinson playing in a Monarchs game described him as having “a big day afield and at bat” against the Black Barons in Birmingham on April 8. “In the game,” the Call continued, “he drove in the first pair of Monarch runs with a line drive to left center.” He had two hits in four plate appearances.4

The April 20, 1945, edition of the Call reported on the tryout of Robinson, Sam Jethroe, and Marvin Williams for the Boston Red Sox held on April 16. The team had been pressured by Boston Councilman Isadore Muchnick to grant the evaluation. Responding to the tryout, in her “Sportorial” column Call sports editor Willa Bea Harmon commented that “if baseball is any one thing, that thing is big business. Robinson’s name means big business if he can play ball.” Harmon also noted that “Robinson’s name is still magic in Sportdom, since he set such a great record at UCLA sometime back in football.” She also reminded Call readers that Monarchs manager Frank Duncan had already labeled the Monarchs rookie “a great one.”

Robinson’s next appearance in the Call was in the April 27, 1945, description of a game in New Orleans against the Indianapolis Clowns, a team about which Jackie undoubtedly had conflicted feelings. He recognized excellent athletes when he saw them, but the antics of the Clowns players likely offended him. According to the Call, Robinson hit an inside-the-park home run after the Clowns center fielder misplayed a fly, and was 2-for-3 in the game. It was one in a series of preseason exhibition games between the Monarchs and Clowns in which Robinson participated.

Also in the April 27 edition, Harmon sarcastically reported that all Robinson and the other players got for their efforts in what turned out to be a sham tryout with the Red Sox was “a little sweat, a train ride at the expense of the [Pittsburgh] Courier and a lot of mumbo-jumbo about how good they looked.”

On May 4, 1945, the Call ran its first picture of Robinson and quoted manager Duncan as saying the rookie was playing very well both defensively and offensively and that the Monarchs management considered Jackie one of the best rookies in recent years. With Jackie in the lineup, according to the Call, the Monarchs infield was a wall and their offense was strong. The record shows that Robinson was indeed contributing on the field, and at the box office as well.

At the Monarchs’ 1945 home and season opener on May 6, 1945, a record-breaking crowd of 13,314 saw Robinson go 1-for-4 in his first appearance at Kansas City’s Ruppert Stadium.5 On May 27 Robinson was perfect at the plate in both games of a doubleheader against the American Giants in Chicago. In the first game he walked three times and singled. In the second contest he doubled, singled, and tripled.6 The next week he was 2-for-5 when the Monarchs took on the Black Barons in Birmingham.7 On Monday night, June 11, 8,100 saw Robinson hit a 350-foot-homer and go 2-for-3 in a game against the Indianapolis Clowns.8

On Sunday, June 17, 16,000 enthusiastic fans greeted the Monarchs rookie at Yankee Stadium, where he singled and scored in a 3-1 win over the Philadelphia Stars. After 27 games, he was batting .345.9

The next Sunday, 20,000 were on hand at Griffith Stadium to see Jackie tie the park record with seven consecutive hits in a doubleheader with the Homestead Grays. On July 4 Robinson moved to first base when the regular first sacker, Lee Moody, was injured.10 On Sunday, July 8, he had two doubles in a game against Birmingham at Ruppert Stadium.11

At times Robinson struggled defensively. Before 30,000 at Briggs Stadium in Detroit on July 22, with Satchel Paige pitching, the Monarchs rookie’s error allowed the Memphis Red Sox to beat the Monarchs, 3-2.12

At an exhibition game against the Sherman Field Flyers of Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, on August 5, with Paige pitching, Robinson drove in two runs.13

Commenting on a Monarchs tour of the East in August 1945, the Call reported that “Jackie Robinson is still the rage everywhere he plays. He is one of the best infielders in the league as well as in Negro baseball. Jackie has keen spirit and is one of the best competitors. He enjoys every minute of every game and performs in a scintillating manner.” Duncan called him “a vital cog in the inner works,” adding, “He scoops up everything that comes his way and his bat has also been a big help to the club.”14

Noting that Robinson was tied with Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe for most home runs in the Negro American League with 5, the Call on August 10 also reported that the “jim-crow” railroad cars the Monarchs were forced to take in the South, were like “the heavily loaded Nazi slave trains which carried men and women to detention camps.” For Robinson, they were just one of many examples of the deplorable travel conditions in the Negro Leagues.

The Call did not report on the signing of Robinson by Branch Rickey for the Brooklyn Dodgers organization in New York on August 28, 1945. Robinson had been sworn to secrecy by Rickey and did not tell the Monarchs he had signed. However, Monarchs co-owners J.L. Wilkinson and Tom Baird knew their star rookie had left the team and traveled to New York without telling them the reason for the trip.

The circumstances of Robinson’s departure from the Monarchs after his meeting with Rickey are somewhat unclear. He apparently asked that he be allowed to leave the Monarchs and return to California on September 21. According to Robinson, J.L. Wilkinson’s son, Dick, chastised him for leaving the team to go to New York without permission and told him he would have to play out the 1945 Monarchs schedule or leave the team immediately. Robinson said he took offense and left the Monarchs.15

Without mentioning that encounter, the September 14, 1945, edition of the Call reported that Robinson would not play in games against the Indianapolis Clowns on September 18 and 19 because he had been suspended. However, in the next week’s edition the Call quoted J.L. Wilkinson as saying emphatically that Robinson had not been suspended from the Monarchs. “He was away from the team for a few days near the end of the season,” Wilkinson stated, “but he was still a member of the team until the end of the season.”

According to Wilkinson, Robinson had not played the last few games because of an injury. He had returned to his home in California. “What his future plans are is not known,” the Monarchs owner wanted it understood, “[b]ut the Monarch fans would be glad to see him again next season. … Jackie left the team with clean hands.”

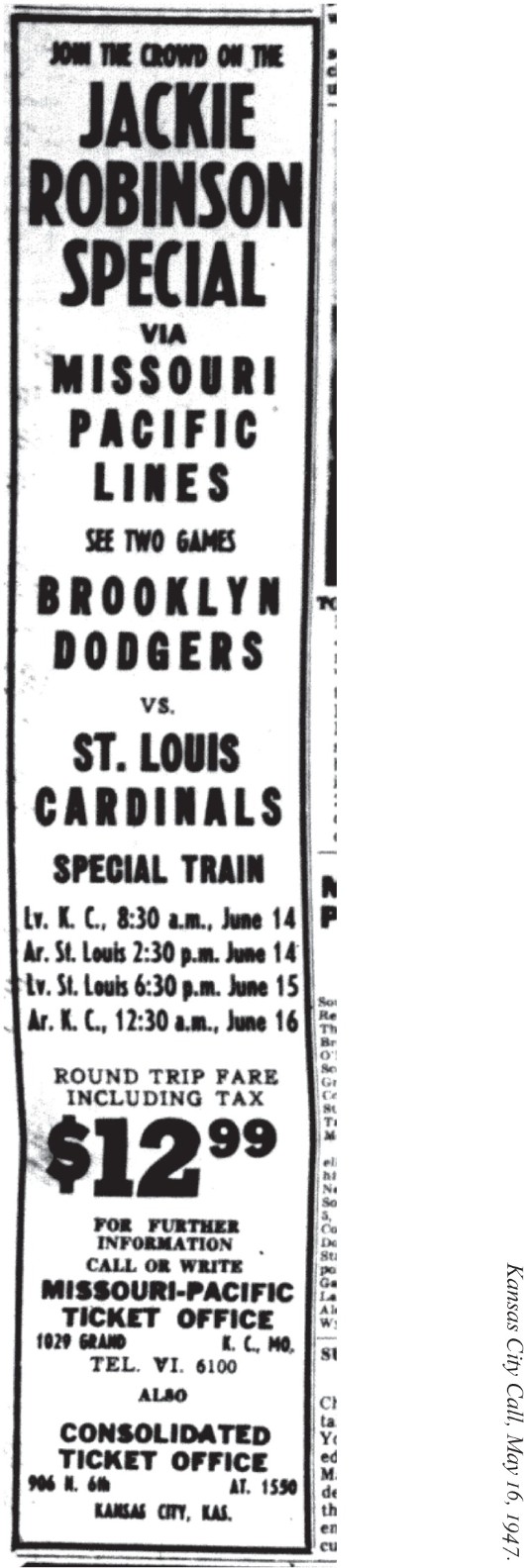

Branch Rickey’s prediction that black fans would flock to see him proved accurate. For an appearance of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ rookie in St. Louis for games against the Cardinals on June 14-15, 1947, Missouri Pacific Railroad organized a “Jackie Robinson Special” to take fans from Kansas City. Needless to say, many who made the trip were Monarchs supporters, whose enthusiasm was now focused more on the former Monarchs player than the team from which Branch Rickey had raided him. (KANSAS CITY CALL, MAY 16, 1947)

According to the October 12, 1945, edition of the Call, Robinson was playing in California for the Kansas City Royals of Los Angeles. A crowd of 9,000 had seen him score the winning run in a game against Butch Moran’s Coast League Stars on September 30 at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles. On October 5, before a standing-room-only crowd at Wrigley Field, the Royals beat the Bob Feller All-Stars, 4-2, with Robinson doubling twice and driving in a run.

When Jackie Robinson agreed on October 23, 1945, to play for the Montreal Royals, the Brooklyn affiliate in the International League, in the 1946 season, the Call noted in its October 26 edition that history was made at the signing, as Robinson “may be considered as the spearhead of Negro integration into baseball.” Branch Rickey Jr., who was present at the signing representing his father, described Robinson as “intelligent and college bred, and I think he can take it too.” In the same edition, the reactions of J.L. Wilkinson and Tom Baird to the signing of Robinson by the Dodgers organization were cited.

From the outset, the two Monarchs owners were publicly supportive, although they felt they had not been fairly treated by Rickey. Tom Baird was quoted as saying, “I am happy to know that Jackie Robinson has been signed to play in the big leagues. It is a well-deserved advancement for the Negro race. He has my best wishes for his success. The Monarchs management stands behind the idea of any man’s advancement. We have no [intent] to hold any player down. I do think, however, that we should have been consulted in the matter. That would have been the proper way, but we shall do nothing to impede Jackie’s progress. He played great ball for our team this season, fielding consistently and hitting .345. Of course, we would be happy to know that he would be with us again next season.”

Two days before, on the basis of an Associated Press report, the New York Times claimed Baird planned to lodge a formal complaint with Commissioner Happy Chandler, telling him: “We won’t take this lying down. Robinson signed a contract with us last year and I feel that he is our property.”16 What seems likely is that the more circumspect Wilkinson convinced his co-owner to change his tone. Wilkinson’s first public statement on Robinson’s signing clearly backed away from his partner’s contention that an appeal to Commissioner Chandler was in order. “Although I feel the Brooklyn club or the Montreal club owes us some kind of consideration for Robinson,” Wilkinson said, “we will not protest to Commissioner Chandler. I am very glad to see Jackie get this chance, and I’m sure he’ll make good. He’s a wonderful ballplayer. If and when he gets into the major leagues he will have a wonderful career.”17

In the October 26 Call article, Baird claimed, “I was misquoted by the Associated Press story, if there was an implication that we are going to start a fight to keep Robinson out of the league, or we’re going to cause him any trouble. We are glad of his advancement and hope more Negro players get the same opportunity. We are not in Negro baseball just to make money; we want to see the Negro race advance to full participation in American activities.”

Also in the October 26 edition of the Call, the reactions of others to the signing of Robinson were outlined. Monarchs secretary Dizzy Dismukes said he had faith in Jackie and believed he would make good on any ball team. Manager Frank Duncan said he supported the selection of Robinson. Walter White, secretary of the NAACP, said, “I am delighted that big league baseball has grown up to its name.” Fans along 18th Street in Kansas City were greeting each other by mentioning the advancement Robinson’s signing represented. The Call then quoted what Robinson had said at the signing: “Of course, I can’t begin to tell how happy I am to be the first of my race in organized baseball. I realize how much it means to me, to my race and to baseball. I can only say I’ll do my best to come through in every way.”

Call editor C.A. Franklin’s editorial on the Robinson signing appeared on November 2, 1945. “Negroes like Robinson who are products of the better colleges in the U.S. know how to get along with their mates,” Franklin commented. “They have no inferiority complex and therefore no chip-on-the-shoulder attitude. Negro players have already proven themselves capable in competition with white major leaguers that goes back to Rube Foster’s Chicago team playing the world champion Cubs.”

Then Franklin directed his comments to the African-American fans. “The Negro player’s success will depend,” he wrote, “on the Negro public. How will they deport themselves under the excitement of the game? Negro fans will have to maintain a brand of public conduct, not merely as good, but far better than the average. Otherwise, White fans would stay away and, forced to choose between old patrons and new, management would get rid of Negro players.”

“Some conduct by Negro fans did not pass muster,” Franklin wanted his readers to understand. He complained about “the chip-on-the-shoulder of those who push throughout the crowd on the street car, and by the thoughtless ones who make noise in the city as though they were all alone in the country.”

Also in the October 26, 1945, edition, the Call’s new sports editor, John L. Johnson, commended Wilkinson and Baird for their support of the signing of Robinson by Rickey, but had a caution. “There should be, however, a lesson in Robinson’s going for owners of Negro clubs,” Johnson wrote. “It is estimated that Negro baseball drew better than $2,000,000 through the turnstiles this year. This is not peanut money. There is considerable cost in training players until they become capable of playing jam-up baseball. If the owners of Negro baseball clubs are not organized sufficiently to prevent any Tom, Dick or Harry from plucking out of their team any desirable player they want, they should so organize, and the sooner the better. If a baseball magnate wants a player, let him pay the price. This is the American way. And any organization that can’t prevent the plucking of its club’s players is a shoddy one and should be reorganized … altogether.”

In his “Sport-Light” column on November 2, Johnson reacted to Branch Rickey’s claim that “Negro baseball is in the zone of a racket” and “I have not signed a player from what I regard as an organized league.” Johnson responded by asking readers, “Isn’t Negro baseball organized? Doesn’t it have rules and regulations to go by; hasn’t Negro baseball an organization with officials empowered to see that players and teams abide by their signed contracts?”

In the November 9, 1945, edition of the Call Johnson had a challenge for fans. He said that Jackie Robinson would likely face his first test with the Royals at spring training in Daytona Beach, Florida. Millions of American Negroes will be pulling for him as their “pathfinder, pioneering in organized baseball, making a way for future Negro ballplayers not yet toddling,” Johnson predicted. “But ‘pulling for him’ is not enough.”

“We should,” Johnson wanted fans to understand, “write letters of congratulations when we approve and letters of strong protest when we do not. Letter writing is second only to voting in advancing our people. Branch Rickey would appreciate thousands of letters approving his stand. He undoubtedly received many disapproving letters. Blues singers used to sing: ‘I can read your letters, but I can’t read your mind.’ … Letters have power. Letters will help Jackie Robinson.”

Of all the reactions to the signing of Robinson, the comment of one anonymous African-American fan, cited in the October 26, 1945, edition of the Call, perhaps said it best: “Yes, sir, democracy means much more to me today than it did yesterday!”

The Call devoted extensive ink to the 1946 season Robinson spent with the Royals. In the April 12 edition of the Call, John L. Johnson claimed that “(w)hatever the future holds for Jackie Robinson and Jim Wright [another African American player Branch Rickey signed], currently playing with the Montreal Royals, no one who admires courage, stamina and the will to win can help but applaud these boys for the job they have done and are doing – for the race and for democracy.”

In the April 26 edition of the Call, a banner headline stated that in Montreal’s opening game in the 1946 International League season, “Robinson’s Homer Helps Royals Top Jersey 14-1.” Johnson exulted that “(m)illions of persons in America heard with pleasure the news telling of Jackie Robinson’s thrilling debut in the league opener against the Jersey Giants.” Then Johnson prophetically predicted that “Robinson’s success in this interracial affair won not only for his team, but also won potential opportunity for many Negro boys who someday will find the route smoother by his performance.”

In virtually every one of its editions during the 1946 season, the Call covered Robinson’s performances in Montreal Royals games. For example, on June 7, 1946, the Call said Robinson was on his way to becoming the champion base stealer in the International League and was batting .347. However, the Call’s editors knew that Robinson’s successes had not magically opened the door for Blacks in other areas of American life. In the same edition, the failure of the Universities of Missouri and Oklahoma to admit African-American students was condemned.

In the midst of its coverage of Monarchs games against the Indianapolis Clowns in its July 26 edition, the Call noted that Robinson had homered in the first game of a doubleheader the Royals played against Syracuse and had four hits in the second game. It also reported that the Monarchs had established the Jackie Robinson Youth League in Kansas City and that Robinson was expected to be on hand to present the championship trophy at the end of the season.

In the August 9, 1946, edition of the Call, Robinson’s role as a “crowd magnet” for the Royals both at home and on the road was featured. In a three-game series at Baltimore, more than 68,000 were in attendance. The next week, the Call quoted Robinson’s Royals manager, Clay Hopper, a Southerner, praising Jackie for the way he “kept his head” during the “intense testing” he had faced and predicting that his prospects in baseball were “unlimited” because he had “the speed, the brains and the ability to play the game.”

In the Call’s September 20, 1946, edition, John Johnson heralded Robinson’s winning of the International League’s batting crown with a .349 average and 155 hits and claimed “(i)t is doubtful any other player could have done so well with the crushing odds that faced him.” In the October 11 edition, the Call’s report on the Montreal Royals winning of the Little World Series climaxed with the shout from the crowd after the clinching game: “We want Robinson!”

Despite his stunning performance in the 1946 season, Robinson was not immune from racial prejudice even among major-league players who knew how good he was. In his November 15 “Sport-Light” column, Call sports editor John L. Johnson quoted Cleveland Indians ace Bob Feller’s claim that no Negro ballplayers, not even Robinson, were of “big league timber.” Johnson responded: Feller has a right to “chomp his chinas” but “methinks that Bobbie’s got a little color phobia in his peepers.”

By the time Robinson joined Brooklyn for the 1947 season, the Call’s coverage of how Jackie was faring with the Dodgers overwhelmed the paper’s reporting on the Monarchs. The imbalance continued throughout the season. For example, an April 18 banner headline exulted, “Robinson Wins Friends Fast on Brooklyn Team.” His first game at Ebbets Field had drawn over 24,000 fans, many Black, the Call noted. In its June 13 edition, the Call gave a banner headline to Robinson’s “perfect day” (two singles, a double, and a triple) against the Cincinnati Reds, while a smaller headline read “Monarchs Drub Clowns.” Jackie’s first spat with an umpire drew comment in the July 4 edition of the Call, alongside the note that the Brooklyn rookie had hit in 18 games in a row and led the National League in steals. When Robinson wrenched his back and had to sit out a game, the September 12 Call took note. Alongside was an ad with Robinson’s endorsement of Homogenized Bond Bread.

When the Monarchs sold the contracts of Willard Brown and Hank Thompson to the St. Louis Browns, John Johnson in his August 1, 1947, “Sport-Light” column in the Call noted that the Monarchs were becoming known as “foremost Negro preparatory school for the major leagues.”

As the 1947 season drew to a close, there was relatively little mention of Monarchs games and players in the Call. The focus was on Robinson and the Dodgers reaching the World Series. For example, the October 3 edition proudly proclaimed that Jackie Robinson was “the first member of his race to play in a World Series game.”

The decline of interest in the Negro Leagues after Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers and the acquisition of other Black players was not unexpected and has been thoroughly documented. It is well illustrated by an ad in the Call on May 16, 1947, for a “Jackie Robinson Special” on June 14 that featured (for only $12.00) a train ride from Kansas City to St. Louis and back for two games between Robinson and the Brooklyn Dodgers and the St. Louis Cardinals.

WILLIAM A. YOUNG is professor emeritus of religious studies at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. He is the author of several books on the world’s religions and, in retirement, two books on the history of baseball: John Tortes “Chief” Meyers: A Baseball Biography (McFarland, 2012) and J.L. Wilkinson and the Kansas City Monarchs: Trailblazers in Black Baseball (McFarland, 2016). For the second book he received a SABR Research Award in 2018. He is a SABR member and resides, with his wife, Sue, in Columbia, Missouri.

Sources

In addition to the Call, portions of this essay are drawn from William A. Young, J.L. Wilkinson and the Kansas City Monarchs: Trailblazers in Black Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2016).

Notes

1 Kansas City Call, December 29, 1939; November 22, 1940; August 8, 1941; September 5, 1941; September 19, 1941.

2 Call, October 27, 1944.

3 Call, March 16, 1945.

4 Call, April 13, 1945.

5 Call, May 11, 1945.

6 Call, June 1, 1945.

7 Call, June 8, 1945.

8 Call, June 15, 1945.

9 Call, June 22, 1945.

10 Call, July 6, 1945.

11 Call, July 13, 1945.

12 Call, July 27, 1945.

13 Call, August 10, 1945.

14 Call, July 27, 1945.

15 Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), 128.

16 New York Times, October 24, 1945.

17 Cited in Janet Bruce, The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Black Baseball (Lawrence: University of Kansas, 1985), 112.