Jackie Robinson’s 1947 Breakthrough Began in Havana

This article was written by César Brioso

This article was published in Jackie Robinson: Perspectives on 42 (2021)

Jackie Robinson playing in a spring training game vs. Havana Cubans. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Separated by fewer than three miles, the Hotel Los Angeles near la Habana Vieja (Old Havana) and the Hotel Nacional in the city’s Vedado district were worlds apart.

Sitting on a bluff overlooking El Malecón, Havana’s famed coastal roadway, the Nacional exuded opulence with its Andalusian-Moorish architecture, elegant bars and splendid swimming pool. And in March of 1947, the Havana landmark housed the Brooklyn Dodgers as they held spring training in Cuba. The Los Angeles was – in the words of Herbert Goren of the New York Sun – a “musty, third-rate hotel” that “looked like a movie version of a waterfront hostelry in Singapore.”1 That was where Jackie Robinson – along with Montreal Royals teammates Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, and Roy Partlow – was staying.

And Robinson was not happy.

“I thought,” Robinson protested, “we left Florida to train in Cuba to get away from Jim Crow.”2

As part of Branch Rickey’s grand plan for integrating major-league baseball, the Dodgers president had opted to move the organization’s spring-training headquarters from Daytona Beach to Havana. He wanted Robinson’s audition for breaking baseball’s color barrier to take place far from fields of Jim Crow Florida. And Havana seemed like the perfect choice.

Cuba’s professional winter league had been integrated since 1900, and the Dodgers were well familiar with the Cuban capital, having held spring training there in 1941 and 1942. Several days after arriving in Havana in 1947, players from the Dodgers and Royals attended the decisive game of the Cuban League season between Almendares and Havana at El Gran Stadium. After Robinson was introduced over the public-address system, “he took bows to the wild shouting of 38,000 jabbering fans,” wrote Baltimore Afro-American columnist Sam Lacy.3 Despite Cuba’s more tolerant racial climate, Robinson and the Royals’ three other African-American players found themselves in separate and unequal accommodations from the Dodgers.

“That damn hotel,” Newcombe said of the Los Angeles years later. “It was full of cockroaches. It was so hot, you couldn’t sleep.” Robinson “hated it with a passion, as did all of us,” Newcombe added. “Jackie was more outspoken about it, but he knew there wasn’t anything he could do about it. He was trying to get to the big club. He had to keep his cool and be quiet.”4

Lacy and Pittsburgh Courier columnist Wendell Smith were two members of the Black press who were embedded with Robinson during spring training, chronicling what they hoped would be his eventual ascension to the majors. Lacy described the Los Angeles as “a fleabag hotel where we slept on heavy spreads that we used for mattresses. The springs were coming up – pressing into our bodies – which shows you just the type of hotel we were in. That was where we had to stay during that period. … The conditions were actually miserable.”5

And Cuba’s relative racial tolerance wasn’t enough to prevent Newcombe from being removed from the lobby of the Nacional one day as he tried to meet with Rickey. “I had to get permission from the bellhop,” he said. “In fact, one [white] bellhop put me out of the lobby. I told him I had to see Mr. Rickey with the Dodgers. I was allowed to go to the house telephone and call Mr. Rickey to get permission to go up to his room to see him.”6

Newcombe, Robinson, Campanella, and Partlow were even segregated from their white teammates on the Royals, the Dodgers’ Triple-A affiliate. While the Dodgers stayed at the Nacional and trained at Havana’s El Gran Stadium, the Royals lived and trained at the Havana Military Academy, a fancy school for the sons of rich Cubans located about 15 miles outside the capital. Every day, Robinson and the other Black players had to be shuttled to that campus before returning to the Los Angeles after each day’s workouts.

Wanting to avoid even the possibility of any disruptive racial incidents in the Royals’ camp, Rickey chose to house Robinson, Campanella, Newcombe, and Partlow separately from the Royals.7 Rickey’s abundance of caution was probably unnecessary. After all, Robinson had spent the entire 1946 season at Montreal, where he led the league in batting with a .349 average.

Montreal was a progressive city, and Robinson normally encountered resistance only when the Royals traveled around the International League, most notably when a riot broke out during an August series in Baltimore as fans swarmed the field after a disputed play at home plate during one game.8

There would be no such problems in Cuba, especially at the Royals’ camp, where Robinson received a surprise visit one day from heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis. Robinson’s teammates, Black and White, looked on like giddy teenagers as Robinson and the Brown Bomber compared golf swings and talked about Robinson’s prospects for making the big club. Before leaving, Louis told Robinson: “See you opening day at Ebbets Field with the Dodgers.”9 The visit was a much-needed morale boost for Robinson, who had to deal with several issues during spring training that made his impending historic breakthrough into the majors appear unlikely:

- Minor foot surgery early in spring training.

- Learning a new position at first base.

- An injury late in camp.

- Resistance among Dodgers players.

- The periodic absence of Dodgers manager Leo Durocher.

Robinson missed only a few days after Dr. July Sanguily, a renowned Cuban physician who was one of the owners of the Almendares team in the Cuban League, removed an irritating callus on Robinson’s toe. His new position, however, caused more stress. Robinson had played shortstop with the Kansas City Monarchs before switching to second base with Montreal after Brooklyn signed him in 1945. The Dodgers were set at three-fourths of the infield with second baseman Eddie Stanky, shortstop Pee Wee Reese, and third baseman Spider Jorgensen. Ed Stevens and Howie Schultz had shared time at first base for Brooklyn in 1946. So Robinson’s most likely path to the majors would be through first base.

Robinson started learning the new position from Hall of Famer George Sisler, who was in camp as a coach. Handed a first baseman’s mitt, Robinson was asked how the new glove felt. “I honestly don’t know,” he responded. “I never had one on before.”10 But Robinson said he was willing to try another position switch: “I’ll play where they want me to play. I never played first, but I’ll try anything.”11 Privately, however, Robinson wasn’t nearly as open to the change. “He didn’t like it at all, but Rickey convinced him that this was his way of getting up to the majors,” Lacy recalled years later. “It was just a case where he had enough problems. He had enough things to be concerned about [than] to give him this additional concern of changing positions and possibly doing poorly.”12

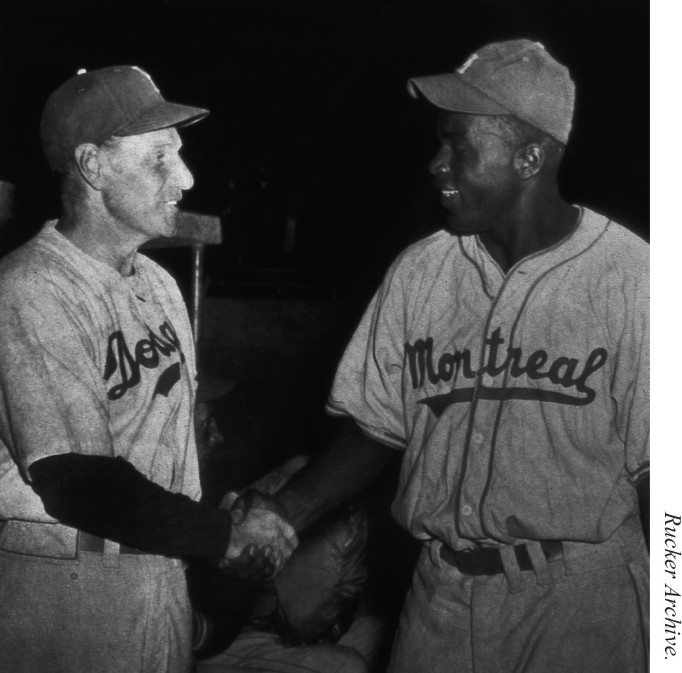

Brooklyn Dodgers manager Leo Durocher and Jackie Robinson at El Gran Stadium. (SABR-RUCKER ARCHIVE)

After opening spring training in Havana, the Dodgers and Royals took a 12-day side trip for games in Panama, against local teams and each other. Opposition to Robinson – in the form of a petition among certain, mostly Southern Dodgers players – came to light during that trip. Dodgers pitcher Kirby Higbe spilled the beans to the team’s traveling secretary, Harold Parrott while out one night at a Canal Zone watering hole. “Ol’ Hig just won’t do it,” a drunken Higbe told Parrott. “The ol’ man [Rickey] has been fair to Ol’ Hig. So Ol’ Hig ain’t going to join any petition to keep anybody off the club.”13

Parrott immediately informed Rickey and Durocher. Unable to sleep after hearing the news, Durocher rousted the players from their beds at the US Army barracks at Fort Gulick, where the team was quartered. Gathered for the impromptu meeting in a huge empty kitchen behind the mess hall, Durocher ripped into his players. “You know what you can do with that petition? You can wipe your ass with it. … I’m the manager of this ballclub, and I’m interested in one thing. Winning. I’ll play an elephant if he can do the job, and to make room for him, I’ll send my own brother home. … So I don’t want to see your petition, and I don’t want to hear anything more about it. The meeting is over; go back to bed.”14

Rickey had hoped the Dodgers players themselves would call for Robinson’s promotion to the majors once they had a chance to play against him, declaring in January: “The players could decide Robinson’s fate. It’s what I prefer – that the Dodgers players make their own decision after seeing him in action.”15 Instead the Dodgers president had to move quickly to quell a rebellion, summoning the mutineers individually to his room at the Hotel Tivoli. The most heated exchange came with catcher and Alabama native Bobby Bragan.

Rickey: “Not you nor anybody else is going to tell me who to play. It doesn’t make any difference whether a guy’s skin is purple, white, green, black, or blue, he is going to play if he’s going to do more than the other guy. Do you understand that?”

Bragan: “Yes, sir.”

Rickey: “Would you rather be traded, or would you rather play with him?”

Bragan: “I’d rather be traded.”

Rickey: “Are you going to play any differently because he’s here?”

Bragan: “No, I’m not.”16

Bragan wasn’t traded, finished his playing career with the Dodgers in 1948, and went on to manage integrated teams in the Cuban League. Playing with Robinson “was the greatest thing that ever happened to me,” Bragan said years later. “Those people, like myself, who might have been a little slow joining Robinson at the breakfast table, we were fighting to see who would eat with him. It was a real transition. He sold everybody.”17

Outfielder Dixie Walker, one of the purported ringleaders of the players revolt, wasn’t summoned to Rickey’s hotel in Panama. He had left the isthmus on March 18, flying to Miami to meet with his family on “personal business.”18 Walker’s confrontation with Rickey would wait until he rejoined the Dodgers after the team returned to Havana on March 22. The Georgia native did not react well. A few days after the meeting, Walker – popular among Dodgers fans and known as the People’s Choice – requested a trade in writing. Handwritten and dated March 26, 1947, Walker’s letter read:

“Dear Mr. Rickey, Recently, the thought has occurred to me that a change of ball clubs would benefit both the Brooklyn Dodgers and myself. Therefore, I would like to be traded as soon as a deal could be arranged. … For reasons I don’t care to go into, I feel my decision is best for all concerned.”19

Unlike Bragan, Walker eventually was granted his request, traded before the 1948 season to the Pittsburgh Pirates, where he finished his playing career after two seasons.

Durocher missed much of the post-petition fireworks, having left for California the morning after his late-night tirade to deal with legal issues surrounding his scandalous marriage to actress Laraine Day. (The divorce from her previous marriage was still pending when she and Durocher wed.) So Durocher didn’t get to see Robinson in action against the Dodgers in Panama. That trend continued even after the Dodgers and Royals returned to Havana to finish out spring training. When he wasn’t making himself the subject of gossip columns, Durocher found himself summoned to a hearing before Commissioner Happy Chandler over his ongoing feud with New York Yankees President Larry MacPhail. The two had sparred verbally over the Yankees’ offseason managerial opening with Durocher penning ghostwritten columns in the Brooklyn Eagle to take swipes at MacPhail.

But their mutual acrimony had come to a head during a game at Havana’s El Gran Stadium on March 8, when gamblers Memphis Engelberg and Connie Immerman were observed sitting in or next to MacPhail’s box – depending on the person telling the story. Durocher, who had been warned by Chandler to stay away from gamblers, and Rickey wondered out loud about MacPhail’s apparent guests. “Did you see those two men out there today, those two gamblers sitting in MacPhail’s box?” Rickey asked the team’s beat reporters.20 “Are there two sets of rules, one applying to the managers and one applying to the club owners?” Durocher said. “Where does MacPhail come off, flaunting his company with known gamblers right in front of the players’ faces? If I ever said hello to one of those guys, I’d be called before Commissioner Chandler and probably barred.”21

An enraged MacPhail denied that Engelberg and Immerman were his guests and filed a grievance with Chandler, arguing that comments made by Dodgers officials “constitute slander and libel” and “represent … conduct detrimental to baseball.” It didn’t help Durocher’s cause that his marriage was creating fallout back in New York, where the Catholic Youth Organization of Brooklyn denounced his conduct on and off the field as “undermining the moral and spiritual training of our young boys.”22

With all the swirling controversies, Durocher finally saw Robinson play for the first time on March 28 in Havana. Robinson, back in the lineup despite ongoing stomach problems, went 1-for-3, but booted two plays at first base that led to four of the Dodgers’ runs as Brooklyn beat the Royals, 5-2. The next day, Robinson played seven innings at first base and went 0-for-2, drew a walk, and stole second base on a pickoff play as Higbe blanked the Royals, 7-0.

In the March 29 edition of the Pittsburgh Courier, Wendell Smith, citing “an unimpeachable source,” reported that Robinson would be promoted to the Dodgers on April 10 and would play first base when the team opened the season on the 15th against the Boston Braves.23 But developments on the field appeared to contradict the certitude of Smith’s reporting. Robinson did not play in the March 30 game won by the Royals, 6-5, and then played second base in games on March 31, April 1, and April 3. Before the March 31 game, Rickey reversed course on the idea of letting the Dodgers players decide Robinson’s fate. “No player on this club will have anything to say about who plays or who does not play on it,” Rickey said. “I will decide who is on it and Durocher will decide who of those who are on it does the playing.”24

Another potential setback came during the game on April 5. Robinson was back at first base, but injured his right arm and back after getting bowled over by Dodgers catcher Bruce Edwards, who was sliding back to the bag. Robinson sat in the stands the next day as the Dodgers beat the Royals, 6-0, in the final exhibition game at El Gran Stadium. Having left Havana after what had been the most expensive spring-training camp in history, with a $50,000 price tag,25 the Dodgers began working their way up the US East Coast in a series of exhibition games before the regular-season opener at Ebbets Field.

What of the Royals’ Black players? Campanella was promoted to Montreal, Newcombe returned for another season at Class-B Nashua, and Partlow had already been released in March. All that remained was a decision on Robinson. The plan was for Durocher to publicly ask Rickey to elevate Robinson, but as the Dodgers brain trust met on April 9 in Rickey’s office on Montague Street in Brooklyn, a call came from the commissioner’s office notifying the Dodgers of Chandler’s decision in regard to MacPhail’s grievance. Aside from fining Parrott and the Dodgers, Chandler suspended Durocher for a year for conduct detrimental to baseball.26 The Dodgers manager would not be present when on April 10 – as Robinson played in his final exhibition game against the Dodgers – Rickey’s assistant Arthur Mann posted a terse release in the press box at Ebbets Field: “The Brooklyn Dodgers today purchased the contract of Jackie Roosevelt Robinson from the Montreal Royals. He will report immediately.”27

CÉSAR BRIOSO is a digital producer and former baseball editor for USA Today Sports. In more than 30 years as a sports journalist, he also has written for the Miami Herald and the South Florida Sun-Sentinel. He is author of Havana Hardball: Spring Training, Jackie Robinson and the Cuban League, and Last Seasons in Havana: The Castro Revolution and the End of Professional Baseball in Cuba, winner of the 2020 SABR Baseball Research Award.

Sources

This article is adapted from Havana Hardball: Spring Training, Jackie Robinson, and the Cuban League by César Brioso (Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida, 2015), updates by the author.

Notes

1 Herbert Goren, “Dodgers Split on Robinson,” The Sporting News, March 12, 1947: 17.

2 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 165.

3 Sam Lacy, “Looking ’Em Over,” Baltimore Afro-American, March 8, 1947: 12.

4 Author interview with Don Newcombe, January 1997.

5 Author interview with Sam Lacy, January 1997.

6 Author interview with Newcombe, January 1997.

7 Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment, 165.

8 Tygiel, 129.

9 Wendell Smith, “A Pair of Kings … of ‘Sock.’” Pittsburgh Courier, March 22, 1947: 14.

10 Tygiel, 168.

11 Goren.

12 Interview with Lacy.

13 Tygiel, 168.

14 Leo Durocher with Ed Linn, Nice Guys Finish Last (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975), 205.

15 Harold C. Burr, “Dodgers Players to Have Voice on Jackie’s Climb,” The Sporting News, January 22, 1947: 16.

16 Interview with Bobby Bragan, January 1997.

17 Interview with Bragan.

18 Roscoe McGowen, “Dodgers Play Tie with Royals, 1-1.” New York Times, March 18, 1947: 37.

19 Maury Allen and Susan Walker, Dixie Walker of the Dodgers: The People’s Choice (Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 2010), 3.

20 Red Barber, 1947: When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball (New York: Doubleday, 1982), 106-7.

21 Barber, 107-8.

22 Jack Lang, “CYO Raps Lip, Quits Knothole Club,” The Sporting News, March 12, 1947: 8.

23 Wendell Smith, “Jackie Robinson Will Play First Base for Brooklyn Dodgers.” Pittsburgh Courier, March 28, 1947: 1.

24 Roscoe McGowen, “Dodgers to Drop 10 Men by Sunday.” New York Times, April 1, 1947: 35.

25 Michael Gavin, “Jackie Robinson Gets Chance with Flatbush Troupe,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1947: 18.

26 Durocher, 257.

27 Louis Effrat, “Dodgers Purchase Robinson, First Negro in Modern Major League Baseball,” New York Times, April 11, 1947: 20.