Jackie Robinson’s Television Appearances

This article was written by Zac Petrillo

This article was published in Not an Easy Tale to Tell: Jackie Robinson on the Page, Stage, and Screen (2022)

“Television is not only just what the doctor ordered for Negro performers; television subtly has supplied ten-league boots to the Negro in his fight to win what the Constitution of this country guarantees as his birthright.” — Ed Sullivan1

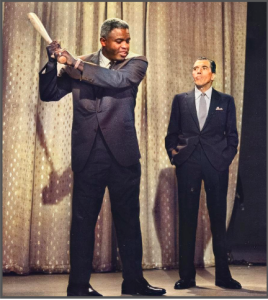

Jackie Robinson appears on The Ed Sullivan Show on May 20, 1962. (Courtesy of Ed Sullivan Estate)

On the November 20, 1969 episode of CBS’s What’s My Line? Jackie Robinson was the surprise guest. One of the panelists, Soupy Sales, excitedly recounted that he watched Robinson play football for the UCLA Bruins way back in 1944. It’s one of the “big thrills of [Soupy’s] life and [he] gets a big kick out of telling people.” Robinson debunks Soupy’s story by saying softly, “Should I contradict him?” Robinson goes on, “I would like to have been in school in 1944,” but Robinson played in the Bruins backfield in 1939.

The moment is gently comical, touching ideas of nostalgia and the trickery of memory.2 More than anything it speaks to a fact of American life from the late 1940s through the early 1970s: Everyone believed they knew Jackie Robinson. His presence was ubiquitous because a generation grew up with him, not only in the news or on the baseball field, but on their television screens, out of uniform, giving batting tips in primetime, discussing beating the odds on talk shows, schmoozing with Hollywood stars at high-profile dinners, and even appearing in bit parts on scripted series.

Spurred by the public unveiling of television at New York’s World Fair, the first broadcast of a baseball game was Princeton versus Columbia on May 17, 1939. Three months later, about 400 television sets in New York could watch Red Barber call the first televised major-league baseball games, a doubleheader between the Brooklyn Dodgers and St. Louis Cardinals on W2XBS (the station that became WNBC-TV).3 It was nearly another decade before the league could take full advantage of the small screen.

World War II stymied consumer development because electronic companies focused their resources on assisting with the war effort. Television programming as viewers came to know it didn’t proliferate American culture until roughly 1947 with such nationally syndicated shows as Mary Kay and Johnny, Puppet Television Theater (Howdy Doody), and Meet the Press. That same year, Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in what was then known as major-league baseball.

The timing proved serendipitous as the first live World Series broadcast was Game One in 1947, which pitted Robinson’s Brooklyn Dodgers against the New York Yankees. “Sunlight and shadows obscured NBC cameras’ view,”4 making the game hardly watchable, but the series still garnered nearly four million estimated viewers between Philadelphia, Washington, New York City, and Schenectady. People huddled around “7-inch and 10-inch screens”5 at tavern gatherings that were responsible for double the audience of home viewership.6 Over the next three years, television ownership exploded to approximately six million homes and as more sets entered the living rooms of average Americans, so too did Robinson.

Robinson’s first major television appearance was on Milton Berle’s NBC variety show, Texaco Star Theater, on September 27, 1949. He was amongst other celebrity guests such as W.C. Fields, Bela Lugosi, and, most notably, tap dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. The sketches, including Berle and Bill Robinson performing “Take Me Out to the Ballgame,” are light and baseball-themed, in line with Berle’s comedic stylings transferred from radio a year earlier.

Less than two weeks later, the Dodgers lost to the Yankees in the World Series for the second time in three seasons. That offseason Jackie Robinson was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player. Shortly after, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson died. Ed Sullivan, the columnist turned popular television host whom Jackie Robinson came to know well, arranged and paid for the funeral. Robinson attended in the company of Milton Berle and fellow television personalities such as actors Jimmy Durante and Danny Kaye. Babe Ruth may have been baseball’s first major star, delivered to the public via national headlines, newsreels, and radio, but Robinson was, in just his third season, the sport’s first star to come directly into households via the small screen.

To supplement his baseball income in the offseason of 1949, Robinson took a job selling television sets at Sunset Appliance Store in Rego Park, Queens. Joseph Rudnick, the store’s owner, commented, “He’s a natural salesman, with a natural modesty that appeals to buyers.”7 But Robinson himself, perhaps proving Rudnick’s point, said, “If a customer is going to buy a set, he’s going to buy it… You can’t twist his arm.” The New Yorker reported that Robinson’s family owned a 16-inch television on which their only child (at the time) Jackie, Jr. liked to watch Howdy Doody, Mr. I. Magination, and Farmer Gray.8

In 1950, Robinson starred as himself alongside Ruby Dee in the film The Jackie Robinson Story. To promote the movie, Robinson made a May 20, 1950 guest spot on Dumont Television Network’s Cavalcade of Stars. The skit begins with Billy, a boy who uses a wheelchair, reading Life magazine with Robinson on the cover. His dad enters bearing birthday gifts, trying to cheer Billy up with the promise of a party where celebrity guests will attend. It’s not until his dad mentions that he will invite Robinson that Billy nearly jumps from his chair, exclaiming, “Jackie Robinson!” Before sinking, “Aw, he wouldn’t come.”9

After a series of failed attempts to sneak into Ebbets Field, Billy’s dad, defeated, tells a concession stand worker that his kid is sick and wishes to meet Robinson. Another small boy overhears. The dad leaves to inform Billy their party will only be them. There’s a knock at the door. Suddenly, the real Robinson is in their living room with the small boy. “I hope you don’t mind our intruding, but my son told me that you wanted to see me,” Robinson says. He hands Billy a glove, but Billy says, “Where will I play baseball… in my dreams?” Jackie replies, “That’s a good place to start…” before telling the story of how he started as a small Black boy amongst older White kids, so good that they couldn’t help but give him a chance. Here is an example of Robinson stepping out from the television and literally into a fan’s living room. The plot doubles in on itself, providing a glimpse into how television allowed fans, who previously only admired ballplayers at a distance, to now feel they knew them intimately.

Throughout the 1950s, Robinson remained a fixture on primetime shows. He appeared with his Dodgers teammates on such programs as Edward R. Murrow’s See It Now and, for his first of multiple appearances, on The Ed Sullivan Show. He was also a solo mainstay on programs like The Ken Murray Show, The Tonight Show hosted by Steve Allen, and On Your Way.

On November 23, 1953, Robinson appeared on a CBS program called Dinner with the President; live coverage of a dinner marking the B’nai B’rith Anti-Defamation League’s 40th anniversary. Prominent guests included senators, supreme court justices, Hollywood performers, and, most tellingly, television broadcasting luminaries David Sarnoff, Leonard Goldenson, and William Paley (heads of NBC, ABC, and CBS, respectively). While ostensibly meant to celebrate breakthroughs in freedom, the entire show was a coronation of television as a medium, as evidenced by a prolonged performance at the show’s center by television’s biggest stars, Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball.

As with most of his early appearances, Robinson’s time on screen was brief and innocuous, meant primarily to spotlight his courage amongst a racially-understanding crowd. While extolling the advancements in American civil liberties, Rex Harrison, one of the event’s emcees, states there was “a lynching a week forty years ago,” but while “there’s still mob violence… in 1952 and in 1953, there has not been a single lynching in the United States.” As politicians and television’s newly-minted elite applauded progress, the fight was far from over, as Jackie no doubt knew. By 1956 another three Black people were lynched in America.10

Following the 1956 season, the Dodgers agreed to trade Robinson to the New York Giants. Rather than accept the trade, Robinson announced to Look magazine that he was retiring to pursue other ventures. “At my age a man doesn’t have much future in baseball and very little security,” Robinson said.11 By that time the general public’s acceptance of the civil rights movement was being tested as the Brown v. Board of Education decision, the murder of Emmett Till, and the Montgomery bus boycott made racial inequality national news and polarized public opinion, shaking the perceived postwar status quo by forcing all Americans to confront uncomfortable truths.

On January 9, 1957, just a day after the Look article hit newsstands, Robinson appeared on CBS’s I’ve Got a Secret. In a rare departure from his normal experiences as a media guest, he was met with something other than warmth. The show’s host, Garry Moore, brings Robinson out amidst a laundry list of his athletic accomplishments (“broad jump champion”; “shot a 71 in golf”), but the conversation turns to his decision to leave baseball and become the Vice President of Personnel at Chock full o’Nuts. Robinson says, “I’m very, very proud to be associated with the organization.” Instead of having a panel of four people ask Robinson questions, Moore announces, “We decided to have a panel of 700, those in our studio audience.” Robinson’s eyes race left and right, uneasy at what might come next.12

Jackie immediately faces questions about whether he will miss baseball and why he quit the Giants even after saying he would play for them. For the first time in his television life, Robinson responds with frustration, firmly explaining that he had a “moral obligation to Look Magazine” for the exclusive story of his post-baseball employment. Next, a man asks if the trade to the Giants was why Robinson retired. Robinson, his voice rising, confirms, “It had absolutely nothing to do with my decision.” Moore tries to defuse the moment by assuring, “Well, that answers that question once and for all.” Still, the next audience member asks the same question: “Did the fact you were traded to the Giants have any bearing on your retirement?”13

As a cloud of discomfort hung over the rest of the show, Robinson graciously answered more questions about baseball. No matter how hard Robinson tried to direct the discussion to his plan to pursue a business career, it seemed the sheen of goodwill surrounding him had worn and fans had less room for adulation if he wasn’t fitting their narrative.

For most of his adult life, Robinson’s political stances aligned with the ideals of America’s popular imagination. He was a supporter of Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower, as evidenced by his appearance at the 1953 dinner. In the 1960 Presidential election, he strongly supported Eisenhower’s Vice President, Richard Nixon. “Robinson had done everything that could be asked of him as an American Hero,”14 but as the country shifted and the 1960s got underway, Robinson’s politics transformed. He traveled to burned churches, spoke in support of the NAACP, and marched on Washington. He supported Nixon because he didn’t feel John F. Kennedy was strong on civil rights. By the end of the decade, Robinson saw a different Nixon and did not support his run for office in 1968.

On May 20, 1962, Robinson, now squarely in the new phase of his public life, made what became his most well-known appearance, this time to offer “batting tips” to young ballplayers on The Ed Sullivan Show. By that point, Sullivan and Robinson had developed a close personal friendship, even cochairing events such as a dinner honoring world heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson at the Commodore Hotel in 1960.15 Before Sullivan hit it huge as the longest-running variety show host on television, he wrote a column during Robinson’s rookie season that began: “Listen, kids” and celebrated Robinson “because he knocked Ignorance out of the park, tagged out Prejudice and trapped the pop-fly of Custom….”16

Robinson had joined his teammates on Sullivan in 1956. He was also spotted in the crowd on another episode, taking a bow during the host’s customary celebrity audience-member introductions. In 1962, Jackie had just been inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame and been named UCLA’s Alumnus of the Year. “We’ve got your model here,” Sullivan tells Jackie, handing him a baseball bat. “My model… this is Willie Mays,” Robinson responds to the laughter of the audience. And then, in another bit of Robinson’s on-screen celebrity commenting on his real-world persona, Sullivan says, “Jackie, that’s show business.”17

Later, as Robinson encourages kids not to imitate professionals, to be themselves, and keep their eyes on the ball, he compares common batting mistakes to the same mistakes people make in golf. To which Sullivan playfully quips, “He’s played with me, so he knows what I do.”18

In 1966, Robinson starred in a minor role on an episode of ABC Stage 67. Titled “The People Trap,” the science fiction story is set 100 years in the future (2067), when the United States is overpopulated, and land is scarce. He was one of many stars with bit parts in the show; others included Cesar Romero and Charlie Ruggles.

Two television appearances late in Robinson’s life exemplify the complexities of his personality. First, in 1970, Robinson appeared on Sesame Street to recite the alphabet. It’s pure Jackie. A careful charm in the precise enunciation of each letter. It’s the Jackie that America thought they knew for over 20 years, the one they wanted to know, one that could make us comfortable with our differences and draw children into needing to learn.

In contrast, his final guest interview was on The Dick Cavett Show on January 26, 1972, less than a year after his oldest son died in a car accident at 24 years old. After a discussion about Jackie’s experiences turning the other cheek in baseball, the kind that had almost become stock for Robinson over two decades, the topic went to Robinson’s efforts to improve Black construction businesses and then to Jackie, Jr.’s drug use and untimely death.

“We were quite proud that our son, in spite of a very serious heroin problem, overcame it,” Robinson explains. “His automobile accident had absolutely nothing to do with drugs.” Even during an uncharacteristically solemn moment, Robinson, a demeanor weathered by years of struggle and tragedy, tries to focus on positive change for the future. “It [drugs] is, to me, the worst problem that we have in this country today,” Robinson continues. “Even worse than the race problem.”19

Roughly nine months after Dick Cavett, Jackie Robinson died at 53 years old. Towards the end of his life, he said, “I guess I had more of an effect on other people’s kids than I had on my own.”20

Robinson not only broke the color barrier in major-league baseball but paved the way for integrating the military and public schools. He energized Americans to support the Civil Rights Act of 1965 and even promoted change within corporate America by becoming the first Black executive of a major company. This was largely because Americans had a relatable and rooting interest in a Black person doing something everyone loved: playing baseball. Even more so, Robinson’s legacy endured because people got to see him as a flesh and blood human via the new medium of television. It was the perfect convergence of a moment. Jackie Robinson arrived along with a vessel by which America could experience him.

***

To research television history is to, at some point, land on YouTube. The space has become an invaluable archival resource thanks mainly to personal copies of early programs digitized for public consumption. As much as the videos are a treasure trove, the adjacent comment sections can be a cesspool of disparaging, hostile, if not downright vile opinions designed only to offend. One learns to keep their eyes up and never drift into the rabbit hole below.

It’s encouraging that the comments on videos containing Jackie Robinson are an alternate universe from why you avert your eyes. Rather than the worst of humanity giddy to tear down an American hero, there are endless expressions of respect:

“The heroism and sacrifice of this prince of a man cannot be overstated.”21

“One of the greatest amerericans [sic] who ever lived”22

“Jackie could’ve been the best politician ever! But I think being one of the best athletes in history will do!!”23

These comments give us a reaction to Robinson, not 70-plus years removed from his Dodgers debut but in real-time. Robinson’s television appearances, most often short and far from subversive, provide the viewer with the way his presence changed the way the average American saw by changing how they saw.

Zac Petrillo has a BA from Hunter College and an MFA from Chapman University’s Dodge College of Film and Media Arts. He has created multiple short films and produced shows for Comedy Central and TruTV. In 2016, he was instrumental in the launch of Vice Media’s 24/7 cable network, Vice TV. As a member of the Society for American Baseball Research, he focuses his work on post-1980s baseball and the cross-section between the game and the media industry. He is currently the Director of Post Production at A+E Networks and teaches television studies at Marymount Manhattan College.

Notes

1 Ed Sullivan, “Can TV Crack America’s Color Line?” Ebony, June 1951: 58-65.

2 Rob Edelman, “‘What’s My Line?’ and Baseball,” Baseball Research Journal, Society for American Baseball Research, Fall 2014.

3 Roscoe McGowen, “First Day for the Small Screen,” New York Times, August 26, 1939

4 Frank Fitzpatrick, “In ‘47, a different ball game,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 20, 2012: D1

5 Frank Fitzpatrick.

6 Joe Csida, “3,962,336 Saw Series on TV,” Billboard, October 18, 1947: 4.

7 John Graham and Rex Lardner, “Success,” New Yorker, January 1, 1950.

8 John Graham and Rex Lardner.

9 “Misc episode of ‘Cavalcade of Stars’, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/Cavalcade, August 17, 2008.

10 University of Missouri-Kansas City, School of Law, Lynching: By Year and Race, http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/shipp/lynchingyear.html

11 James F. Lynch, “Jackie Robinson Quits Baseball; Trade is Voided,” New York Times, January 6, 1957: 1.

12 rrgomes, “Joe E. Brown and Jackie Robinson on “I’ve Got a Secret” (January 9, 1957) – Part 3 of 3, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7i0uqS4xWyM, August 15, 2011.

13 Joe E. Brown and Jackie Robinson on “I’ve Got a Secret” (January 9, 1957) – Part 3 of 3.

14 Sridhar Pappu, “An ill and unhappy Jackie Robinson turned on Nixon in 1968,” The Undefeated, November 17, 2017.

15 UPI, “Today’s Sports Parade,” Hugo Daily News (Hugo, Oklahoma), July 17, 1960: 5.

16 Ed Sullivan, “Little Old New York,” Daily News (New York), September 17, 1947: 59.

17 The Ed Sullivan Show, “Jackie Robinson “Batting Tips” on The Ed Sullivan Show, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hgIWwGXlgag, July 23, 2020.

18 “Jackie Robinson “Batting Tips” on The Ed Sullivan Show”

19 Pianopappy, “Jackie Robinson interviewed on the Dick Cavett Show,” Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YCr0RAzf8ds, April 17, 2018.

20 “An ill and unhappy Jackie Robinson turned on Nixon in 1968.”

21 Frank Russo, “Whats My Line Jackie Robinson,” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mvsSxxPoAHU, September 10, 2010.

22 LittleJerryFan92, “Sesame Street – Jackie Robinson Recites the Alphabet,” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KKSKQc9DmI4, June 3, 2007.

23 “Joe E. Brown and Jackie Robinson on “I’ve Got a Secret” (January 9, 1957) – Part 3 of 3.