Jerry Sullivan: Forty-Six Years Before Eddie Gaedel

This article was written by Dennis Snelling

This article was published in The National Pastime: A Bird’s-Eye View of Baltimore (2020)

The city of Baltimore has hosted a number of historic baseball events. Although this story barely qualifies as such, it is nevertheless an interesting aside involving Jerry Sullivan, a 32-year-old, 3-foot-11 stage actor who appeared in an Eastern League game in Baltimore in 1905. Forty-six years later, the St. Louis Browns famously inserted 3-foot-7 Eddie Gaedel into a major league contest as a pinch-hitter. However, unlike Gaedel, Sullivan wielded a regulation bat. Not only that, he singled and scored a run. (There is no evidence Sullivan’s feat inspired Bill Veeck’s stunt of hiring Gaedel, or that Veeck even knew about it.)

The game in which Sullivan participated has been documented previously — with varying degrees of accuracy — standing in stark contrast to the meager facts previously published about his life. The events that conspired to bring Jeremiah David Sullivan to home plate in Baltimore began with his birth on August 12, 1873, in Low, Québec, a logging town founded by Irish immigrants.1 Jerry’s name honored his twenty-year-old brother, who drowned two months before Jerry’s birth while driving logs downriver.2

Jerry’s head and torso developed normally during infancy but his extremities did not, and doctors informed the family that their son would never reach four feet in height. Often ridiculed at school, Jerry later revealed he had learned to entertain in the classroom — his defining moment a second-grade assignment requiring the presentation of a humorous verse to classmates. Jerry was astonished when his recitation elicited laughter and approval, and he claimed to have returned to his seat “a bit wobbly.”3

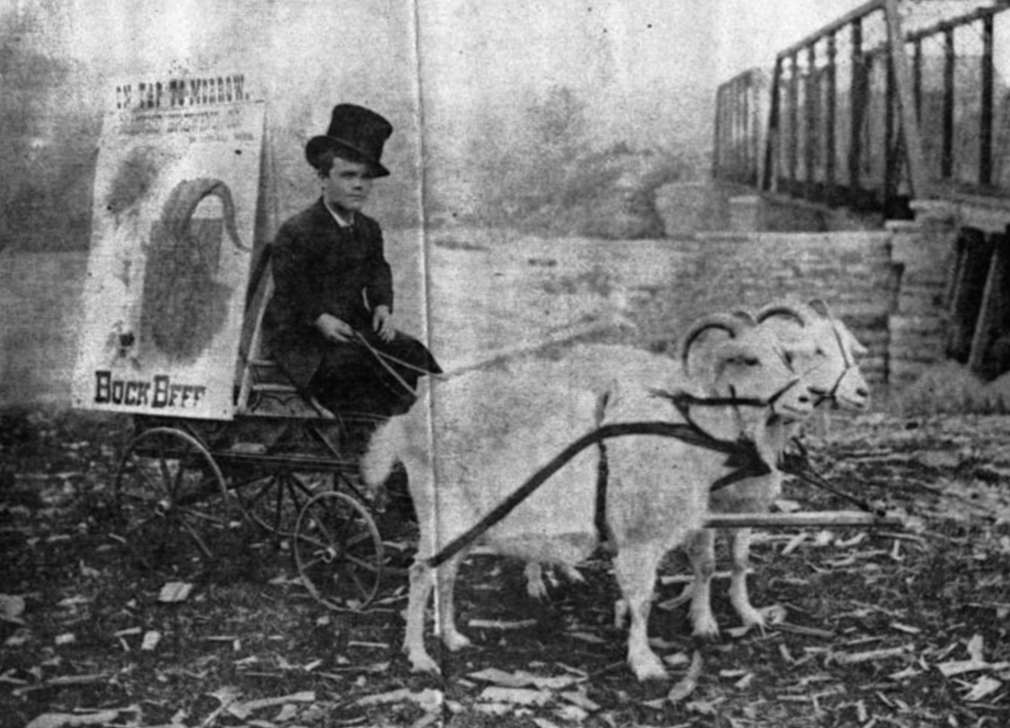

Jerry moved soon after that with his family to Wausau, Wisconsin, where physical limitations, both real and perceived, ended his schooling and limited his career options.4 He began capitalizing on his ability to generate laughs. The local newspaper published a photograph of a teenage Jerry driving a tiny wagon pulled by a pair of goats. The wagon carried a large placard for the Mathie Brewing Company, promoting their bock beer, a strong German ale traditionally consumed by Wisconsinites each spring.5 Buoyed by the promotion’s success, Jerry left home to become an acrobat and contortionist with the Robinson Family Circus, and with a traveling medicine show hawking a “cure-all” elixir sold by Hamlin’s Wizard Oil Company.6

Jerry Sullivan, age 17, promoting the Mathie Brewing Company’s bock beer.

Jerry Sullivan, age 17, promoting the Mathie Brewing Company’s bock beer.

During his travels throughout the US and Canada for Wizard Oil, Jerry occasionally exploited his athletic ability and comic timing in local baseball games. As early as 1892, a town team in Carroll, Iowa, drafted him to play against a female baseball squad from Denver. Sullivan stole the show, hitting a double while serving as the team’s catcher. Judging his performance behind the plate “wonderful,” an anonymous journalist proclaimed, “Little Jerry is a curiosity and to see him play ball is worth all the cost to attend the entire performance.”7

When the Wizard Oil troupe visited Missoula, Montana, Jerry offered to umpire a rematch between Missoula’s town team and that of nearby Anaconda.8 Missoula achieved its revenge, a 26-2 win, with Sullivan praised as “the best umpire that has officiated the grounds this season and was a whole circus in himself.”9 The Anacondans were so impressed they invited him to join them the next week as a player. “He can catch, throw and hit with the best of them,” it was said after that contest, “and he is no slouch on the bases.”10

In 1899, Jerry made the vaudeville circuit and demonstrated his impressive athleticism with a popular tumbling act, mixing in some comedy wrestling along the way.11 His talent caught the attention of Gus Hill, a nationally renowned entertainer thanks to his amazing ability as a juggler of Indian clubs. Looking to expand his horizons, Hill was dipping his toes into the business end of vaudeville by forming a repertory company he dubbed the “Royal Lilliputians.”12 Jerry eagerly signed on; his signature moment involved steering a miniature fire engine pulled across the stage by a goat — an echo of his first taste of fame for Mathie Brewing. Hill then cast Sullivan in McFadden’s Row of Flats, a farce based on the comic strip The Yellow Kid, and in his national touring company of Simple Simon Simple. In Simple Simon Simple he played a featured character named Mose, who made his entrance by popping out of a laundry basket in which he had hidden, a startling introduction that always surprised and delighted audiences.13

Jerry Sullivan also found love, marrying Helen “Nellie” Bates, a chorus girl in the Simon production, at City Hall in New York City the day before St. Valentine’s Day 1901. Nellie’s father, who had discouraged her show-business ambitions, was less than thrilled at the turn of events. When interviewed at his home in St. Louis he remarked, “About a week ago I heard my daughter was going to marry this dwarf. I was surprised, as any father would be, at such news. But…she is old enough to know her own business, and I did not attempt to prevent it.”14

Nellie — who had adopted the stage name Helen von Deleur — said of her new spouse, “I saw him before I went on the stage two years ago and I fell in love with him at once. Then I got into the business and came into the same company last September and he fell in love with me.” When asked about the height difference — Nellie was 5-foot-4 — she laughed, “He’s mighty little for a husband, but I think it will be nice to have a husband I may pick up and shake when I feel like it.”15

More than a decade later, the Sullivans were among several stage couples profiled in a New York Press article and Nellie had grown weary of the inevitable questions, tersely responding, “One day we found out we were loving one another. Then we got married. Is there anything more to say about it?”16

Jerry Sullivan crisscrossed the country continuously for the next several years. While in Baltimore for Simple Simon Simple in September 1905, he crossed paths with Buffalo Bisons manager George Stallings, the man who would lead Boston’s “Miracle Braves” to a World Series title nine years later. The night before Buffalo was to play the Baltimore Orioles in a doubleheader, the notoriously superstitious Stallings spied Sullivan in a hotel lobby. He likely considered Sullivan a totem — in that era it was thought young African-American males, hunchbacks, and those with dwarfism proffered good luck. A hunchbacked little person was even better. Many sports teams employed them as human talismans.

Sullivan’s experience entertaining baseball fans further aroused Stallings’s interest and he invited the diminutive actor to the ballpark the next day to sit on the Bison bench. Buffalo was running out the string, giving Stallings some license, while Baltimore was only two games behind first-place Jersey City in the standings.

A delighted Stallings greeted Sullivan at the ballpark, and had his new pal take part in pregame practice. As the first game was about to begin, Jerry was escorted to the coaching lines by Bisons pitcher Rube Kisinger, mostly for the comic effect of seeing Kisinger, one of the team’s largest players, juxtaposed with a confidently striding Sullivan standing an inch short of four feet in height. Jerry “coached” for a couple of innings, entertaining the crowd as the Orioles jumped out to a 10-2 lead.17

After Buffalo’s Frank McManus singled in the ninth inning, Stallings summoned a pinch-hitter for pitcher Stan Yerkes. It was normal to see a substitute in that situation — what caught everyone off-guard was his identity. It was Jerry Sullivan, carrying a bat nearly as large as he was.18

The umpire formally announced Jerry’s entrance and the actor strutted to the plate while Baltimore pitcher Fred Burchell struggled to contain his laughter.19 After Burchell’s first pitch sailed high, he aimed the next one a little lower and Sullivan shocked everyone by swinging, looping the ball into left field as McManus ran to second.

Burchell attempted to pick-off the pint-sized baserunner. Sullivan scurried back safely, ducking between first baseman Tim Jordan’s legs and sitting down on the bag. Burchell made several more pick-off attempts but Sullivan was wise and remained safely within reach of first base.

Turning his attention to the batter, Burchell surrendered a single to Jake Gettman, scoring McManus while Sullivan scampered to second, putting an exclamation point on his accomplishment by hopping affirmatively onto the base with both feet. Burchell then threw a pitch over the catcher’s head and Sullivan scooted to third to great applause. Frank LaPorte, who a week later would make his major league debut with the New York Highlanders (now Yankees), lined out yet another single — adrenaline flowing, Sullivan played to the crowd in completing his circuit around the bases, punctuating his tally with an elaborately unnecessary slide into home plate.20 Buffalo ultimately scored four runs in the inning, but it was not enough and the Bisons lost, 10-6.

Despite his 1.000 batting average, Sullivan returned to stage work. Six weeks after his baseball diversion he appeared in Simple Simon Simple at Broadway’s West End Theatre, thereby briefly reaching the “big leagues” in his chosen profession.21 He continued traveling the country in Simon, which proved especially popular in the South, and in McFadden’s Flats, spending forty-nine weeks on the road.22

During the summer of 1907, Sullivan braved a deadly heat wave in Philadelphia to attend the National Elks Convention. Awarded the title of “Littlest Elk,” he earned a cash prize and the honor of participating in a massive parade through the city streets, accompanied of course by the “Tallest Elk.”23

Around this time, 22-year-old Bud Fisher created a comic strip that would alter Sullivan’s life. It debuted in the San Francisco Chronicle sports pages on November 15, 1907, as A. Mutt, featuring a character Fisher had created for a previous project.24 A few months later, “Jeff” made his first appearance as the diminutive sidekick to the long, gawky Mutt, and the two confronted a series of continual misfortunes, first connected to bad luck at the racetrack and later involving all manner of ill-fated get-rich-quick schemes.25

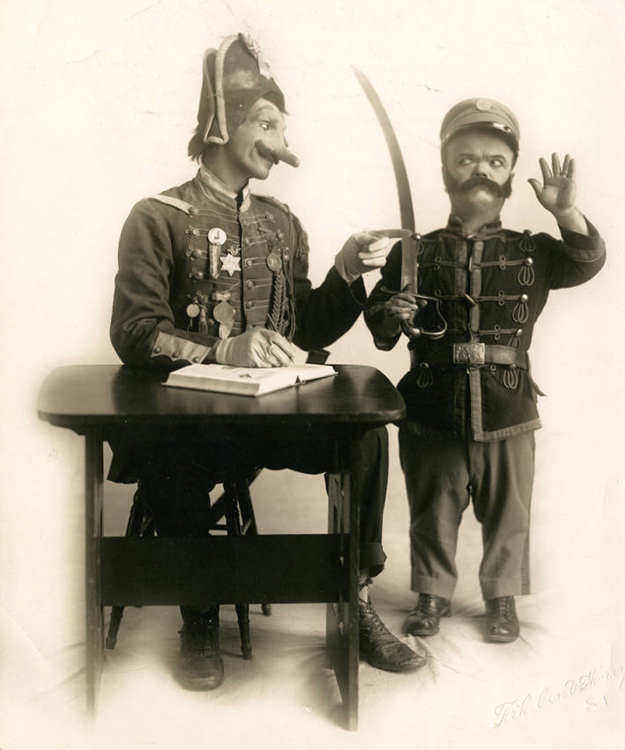

Jerry Sullivan in “Mutt and Jeff”

Jerry Sullivan in “Mutt and Jeff”

Retitled Mutt and Jeff, King Features syndicated the strip nationwide. Gus Hill secured the rights to stage the characters in a series of musical extravaganzas — with up to six companies on the road simultaneously — and Jerry Sullivan spent the next two decades as “Jeff,” performing all over North America. Bud Fisher would earn five thousand dollars a week from his creation, of which he had wisely retained ownership.26

Sullivan would earn much less than that. The life of a traveling vaudevillian produced notoriety, but little else. It was a vagabond existence, with most actors required to cover their own expenses.

He appeared in a few motion pictures — unfortunately among the thousands of early silent films lost over the years. When The Court Jester played in his hometown, the newspaper crowed, “Come and See Jerry Sullivan, a Wausau Boy.”27 A review in Moving Picture World said of Sullivan, “In this film the dwarf who made such a favorable impression in the fairy story The Little Old Men of the Woods plays a prominent part, and he does it, if anything, better than he performed his earlier task.”28 While conceding the “immortality” that film offered an actor, Sullivan, pontificating while puffing on a cigar, asserted his strong preference for the theater. “No matter what stage of perfection motion pictures reach,” he insisted to a reporter, “a play by living people will always be the principal source of amusement.”29

A final baseball reference for Sullivan appears in 1915, a three-inning pick-up game between two show business teams in New York. A recounting of the event calls him “the best player” and noted, “…his versatility has brought him much fame.”30

As the above quotation implies, one would be hard-pressed to locate a negative review of Jerry Sullivan. Hundreds of newspapers praised him, often as a local favorite making a return visit. During a wildly popular two-week run, the San Francisco Call declared, “Besides being a class A ‘funny’ man, Sullivan is a contortionist and athlete of no mean ability.”31 His fans in Texas considered him the obvious successor to the legendary Tom Thumb.32 More than two hundred Elks enthusiastically welcomed him to Roseburg, Oregon in 1916, with a parade through the streets of the town in which he had briefly lived.33

Nine-year-old Eloise Buch, hospitalized in Baltimore in March 1914 with a life-threatening illness, was perhaps Jerry’s biggest fan. After she requested to see “Jeff” in person, Sullivan twice visited her and was astonished to discover she had committed many of his lines to memory.34

Jerry was also a prankster. Since his head and torso were normal size, one of his favorite tricks involved walking into a restaurant and requesting a booster seat. While the server was off on his mission, Jerry would take a regular seat at the table and watch with amusement when the waiter returned and searched for him in vain.35

Sullivan continued playing “Jeff” through the mid-1920s. However, the advent of sound in motion pictures resulted in a precipitous decline in vaudeville’s popularity, and Jerry’s fortunes took a sadly parallel track. He briefly returned to circus life in 1929, before joining two other little people for shows at Wonderland on Coney Island.36 Jobs scarce, Jerry began frequenting the bar at the Circus Room of the Cumberland Hotel in New York, to ill effect.37

He moved into the Luna Villa, a three-story residential hotel on Coney Island, near the amusement parks where he could occasionally find odd roles, including a sideshow in which he was billed as “Jerry the Dwarf.”38 In September 1937, Sullivan was placed under arrest after drunkenly standing on a street corner and heckling a dozen members of the American Legion, shouting at them, “You’re all phonies. You’ve never been across the seas. I could lick you.”39 The Legionnaires laughed it off, but when a police officer advised Jerry to “mind his own business or he might get hurt,” Sullivan challenged the officer, culminating in a visit to the drunk tank.40 Hauled before a judge the next morning, Sullivan gave the magistrate a military salute. Admitting having been drunk he insisted, “I’m all right now.” The judge asked, “Will you be a good boy from now on?” The 64-year-old replied in the affirmative and received a suspended sentence. His career as an entertainer went unmentioned.41

In December 1940, Sullivan attended the funeral of five-hundred-pound “Jolly Irene,” a former Barnum & Bailey sideshow performer with whom he had appeared at Coney Island.42 The marriage with Nellie was certainly all but over by this time; the Census that year listed Jerry as married, but living alone.43

Sullivan then disappears. He likely died before 1953; his brother William passed away that year and Jerry was not listed among the surviving siblings.44 Sadly, Jerry Sullivan’s fascinating life and considerable talents as an acrobat and comic have been almost completely forgotten — except for the day in Baltimore when he swung a baseball bat.

DENNIS SNELLING is a three-time Casey Award finalist for Best Baseball Book of the Year, including for “The Greatest Minor League: A History of the Pacific Coast League,” and “Lefty O’Doul: Baseball’s Forgotten Ambassador,” which was runner-up for the award in 2017. He was a 2015 Seymour Medal finalist for “Johnny Evers: A Baseball Life.” Snelling is an active member of the Dusty Baker & Lefty O’Doul SABR chapters in Northern California, and is an Associate Superintendent for a school district in Roseville, California.

Sources

All photos are in the public domain.

Ancestry.com

California State Library

Duluth Public Library

Familysearch.com

Genealogy Bank.com

Google Books

Internet Archive

Newspapers.com

San Francisco Public Library

Notes

1 World War I Draft Registration Card, Jeremiah David Sullivan, September 11, 1918.

2 “John Kelly & Mary Douglas Family History,” provided by Dot Fischer, November 7, 2018.

3 Jackson (MS) Daily News, November 8, 1912, 6.

4 United States Census, 1940.

5 Janin Friend, “A Forgotten Easter Tradition,” Wausau Daily Herald, March 31, 1983, 24.

6 Green Bay Press Gazette, March 21, 1893, 3. Hamlin’s Wizard Oil was a “cure-all” tonic patented by a magician. As was the case with such elixirs, it consisted mostly of alcohol. Performers sang from wagons, eventually gaining popularity such that they performed in local opera houses and other stage venues, adding specialty acts such as Jerry Sullivan.

7 Carroll (IA) Sentinel, October 15, 1892, 3.

8 Daily Missoulian, June 16, 1895, 1; June 22, 1895, 2.

9 Anaconda Standard, June 17, 1895, 6.

10 Anaconda Standard, June 24, 1895, 3.

11 St. Paul Globe, December 7, 1899, 6.

12 Buffalo Enquirer, July 20, 1900, 5.

13 Daily Illinois State Register, November 5, 1900, 6.

14 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 22, 1901, 8. The attitude of Nellie’s father was influenced by his wife’s abandonment of the family a year earlier to pursue acting studies in Brooklyn, resulting in a divorce that made headlines in St. Louis. (St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 11, 1899, 1; November 12, 1899, 8; December 7, 1899, 10).

15 St. Louis Republic, February 22, 1901, 1.

16 New York Press, December 8, 1912, 6.

17 Buffalo Enquirer, September 21, 1905, 10.

18 Baltimore Sun, September 19, 1905, 8, Buffalo Courier, September 19, 1905, 9.

19 Buffalo Courier, September 19, 1905, 9; Buffalo Morning Express, September 19, 1905, 9.

20 Baltimore Sun, September 19, 1905, 8; Buffalo Courier, September 19, 1905, 9; Buffalo Enquirer, September 21, 1905, 10.

21 New York Times, October 29, 1905, 3.

22 Montgomery (AL) Advertiser, November 24, 1906, 10; Billboard, August 17, 1907, 33.

23 Philadelphia Inquirer, July 15, 1907, 5; July 18, 1907, 4. Jerry also performed at the Lit Brothers department store, with several other entertainers. (Philadelphia Inquirer, July 14, 1907, 5.)

24 San Francisco Chronicle, November 15, 1907, 8; November 16, 1907, 5; November 17, 1907, 17.

25 San Francisco Chronicle, March 27, 1908, 8.

26 The Economist, December 22, 2012; Don Markstein’s Toonpedia, toonpedia.com/muttjeff.htm, accessed February 4, 2020.

27 Wausau Daily Herald, May 4, 1910, 8.

28 Moving Picture World, March 12, 1910, Volume 6, Number 10, 384.

29 Baltimore Sun, March 9, 1914, 4.

30 New York Evening World, June 28, 1915, 14.

31 San Francisco Call, February 10, 1913, 4.

32 Houston Post, October 8, 1916, 41.

33 Roseburg Review, March 15, 1916, 1 & 6.

34 Baltimore Sun, March 14, 1914, 12 & 16. Eloise recovered, eventually becoming a public health nurse. (York Dispatch, July 30, 1981, 42.)

35 Asheville Citizen, September 11, 1907, 6.

36 Billboard, July 27, 1929, 80.

37 Billboard, February 9, 1935, 65.

38 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 1, 1940, A13.

39 Camden (NJ) Courier-Post, September 24, 1937, 5.

40 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 24, 1937, 6; New York Daily News, September 24, 1937, 10. Wire services distributed the story nationally.

41 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 24, 1937, 6.

42 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 1, 1940, A13.

43 United States Census, 1940.

44 Duluth Tribune, December 5, 1953 5.