Kenichi Zenimura, ‘The Father of Japanese American Baseball,’ and the 1924, 1927, and 1937 Goodwill Tours

This article was written by Bill Staples Jr.

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

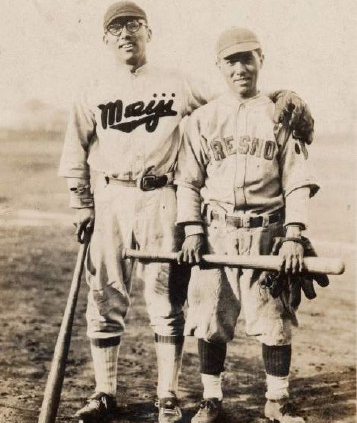

Kenichi Zenimura (right) with his cousin Tasumi Zenimura (left) in 1928. (Rob Fitts Collection)

Few baseball fans know the story of early twentieth-century Nikkei (Japanese American) baseball. Despite this lack of awareness, the Nikkei impact is still visible in today’s game. It’s subtle, though, visible only to the well-informed. The legacy is not a retired uniform number displayed inside a major-league ballpark, but the names on the back of the uniforms. In 2022 those names are Akiyama, Darvish, Kikuchi, Maeda, Ohtani, Sawamura, and Suzuki—and in 2025, it will almost certainly include Ichiro on a plaque in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.1

The national pastime has unofficially become the international pastime, and this is the enduring legacy of Nikkei baseball and the work of pioneers like Kenichi Zenimura (1900-1968).2

During the years 1923 to 1930, no major-league team barnstormed in Japan.3 The highest-caliber competition from the United States during this time came in the form of Nikkei and Negro League teams like Zenimura’s Fresno Athletic Club (FAC) and the Philadelphia Royal Giants. During this major-league void, Nikkei and Negro Leaguers helped elevate the level of play in Japan and set the stage for the 1931 and 1934 tour of stars like Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth, and the start of the professional Japanese Baseball League in 1936.

In 1962 Zenimura was crowned the “Dean of Nisei Baseball” by veteran Fresno Bee sports reporter Tom Meehan.4 Shortly after Zeni’s death in 1968, the same sentiment was echoed by Bee reporter Ed Orman.5 Approximately 25 years later, baseball historian Kerry Yo Nakagawa refined that tribute for a new audience, calling Zenimura “The Father of Japanese American Baseball.”6 Nakagawa and others believe that Zeni deserves this title for his unparalleled career and collective impact as a player, manager, and global ambassador.

PREWAR GOODWILL AMBASSADOR

Between 1905 and 1940, roughly one out of four (26.5 percent) tours across the Pacific featured a Nikkei team visiting Japan.7 When examining the tours between 1923 and 1940, Zenimura’s impressive impact becomes apparent. Of the 53 tours during this period, Zenimura was involved, to some degree, with 17 (32 percent) of those efforts.8 When he himself was not traveling, Zeni supported or influenced 14 different tours by other Nikkei teams, visiting Japanese ballclubs, Negro League teams, and major-league all-stars.9

The following is an in-depth look at Zenimura’s three major tours—1924, 1927, and 1937—in which he participated directly, allowing him to shine in his homeland of Japan.

THE 1924 TOUR

The seeds for Zenimura’s 1924 tour were planted on Independence Day in 1923 when the Fresno Athletic Club battled the Seattle Asahi for the National Nikkei Baseball Championship. The Asahi had earned the respect of the baseball world by winning the majority of their games during tours to Japan between 1915 and 1923.10 In a best-of-three series, the FAC defeated the Asahi to become the undisputed Nikkei baseball champions. With the victory, Fresno also won the right to tour Japan the following year.11

In preparation for the tour, the FAC scheduled games against high-caliber competition, including the Pacific Coast League Salt Lake City Bees, who conducted spring training in Fresno. In a three-game series, the FAC surprised the Bees with a 6-4 victory in game one, marking the first time a Nikkei team defeated a PCL ballclub.12 The series also marked the presence of Frank “Lefty” O’Doul. Newly signed from San Francisco, O’Doul did not compete in the loss, but his powerful bat helped the Bees take games 2 and 3.13

More important than O’Doul’s on-field performance was the historical significance of his involvement. The gregarious southpaw would later be enshrined in the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame for his life’s work as a celebrated ambassador of US-Japan baseball relations.14 Most likely, this 1924 encounter marks O’Doul’s first interaction with ballplayers of Japanese ancestry.

On September 2, 1924, the FAC boarded the SS President Pierce for Japan.15 Six weeks later they stepped inside Koshien Stadium to play their first opponent, Daimai. The FAC recorded a shutout 5-0 victory behind the arm of Kenso “The Boy Wonder” Nushida. Fresno pitchers did not allow a run until their third game, on October 14, a 4-3 loss in a rematch with Daimai.16

During their 46-day stay in Japan (October 11 to November 26), the Fresno team traveled approximately 1,300 miles (about 2,100 kilometers), covering nine cities—starting in Osaka, with stops in smaller locales between Hiroshima, Tokyo, and Yokohama. They played 27 games, finishing with a 20-7 record and an overall .741 winning percentage.17

After watching the Fresno captain compete on the field, a reporter with the Japan Times wrote, “Zenimura is one of the smartest and most colorful players the writer had ever seen. He was the terror of the diamond, a man who played every position in baseball. He was tricky, shrewd and positive poison to every opponent.”18

In Tokyo, Zeni penned his thoughts on the Japan tour experience in a letter to the Fresno Morning Republican, which was published on December 5. It read:

Tokyo, Japan

November 16, 1924

Mr. T.P. Spink

Sports Editor,

The Republican.

Dear Sir: –

The Fresno team is doing a [sic] good work in Japan and so far our record stands 18 victories and 5 lost. In today’s game we played against Keio and defeated them by the score of 8-to-4. We gave the last four runs in the last of the ninth after two men gone.

In Japan it doesn’t pay to win a game in a far margin. If we do then there won’t be any crowd coming to the next game, saying that we are too strong for this Japan team and so on. We had many examples in Osaka.

Beat Diamonds

One day we played against the pro team of Osaka which is known as Diamonds and in our first game we defeated them by a score of ll-2. In this game quite a many fans [sic] came to see the outcome but on the following day with the same teams there was hardly any people in the stand[s]. For this reason, it is hard for the visiting team to play a game in Japan.

Another thing disadvantaging us is the way these Tokyo umpires calls [sic] on decisions against us. … I can’t figure the way these umpires make a bad decision when ever the play is close. We had enough of the raw decisions in Tokyo, but what can we do in Japan!!!

Meet Champions

Tomorrow we are playing against Waseda, the intercollegiate champions of Japan. We hope to beat them badly and by the time this letter reaches you, you will be able to get the result.

On the way to the States I am figuring of stopping over to Honolulu and spend my Christmas and New Year’s there. About five of the players are going to do the same and eleven of the remaining players will be in Fresno by 13th of December 1924.

As soon as the team reaches to Fresno we would like to play a three game series with the Fresno Tigers.

Yours truly,

K. ZENIMURA

(Captain).19

The Waseda contest mentioned in the letter resulted in a 3-2 loss for Fresno. FAC lost the game, but won the respect of the opposing manager, Chujun Tobita. He praised the visiting team’s baseball skills, saying they were “amazing” in their demonstration of technique and power.20

***

Zenimura’s next goodwill tour would not occur for another 16 months (April 1927); however during this period the FAC competed against the all-Black semipro Los Angeles White Sox, a strong West Coast African American club, forming a connection that eventually made a huge impact on US-Japan baseball relations.

On September 6, 1925, the FAC traveled to White Sox Park in Los Angeles to play a doubleheader, the first against the “Diamond Japs,” the visiting Daimai Club from Japan, and then an afternoon contest with the Los Angeles White Sox, led by manager Lon Goodwin.21 Behind the pitching of Nushida, the FAC defeated the White Sox, 5-4.22

The following year, the FAC and White Sox scheduled a rematch, a doubleheader in Fresno over the Fourth of July weekend. The FAC won both games, 9-4 and 4-3.23 This series created the opportunity for Zenimura and Goodwin to discuss plans for parallel tours of Japan the following year. On December 21, approximately five months after their two-game series in Fresno, the Nippu Jiji reported that Goodwin’s Los Angeles White Sox had received an invitation to tour Japan from officials in Fukuoka City, one of the locations where the FAC competed during the 1924 tour.24

The Fresno Athletic Club on their 1927 Asian tour (Courtesy of Bill Staples Jr. and the Nisei Baseball Research Project)

THE 1927 TOUR

In early 1927 the FAC announced plans for a second tour of Asia. The schedule called for 40 games in Japan, China, and Korea, and a stop in Honolulu on the way home.25 The Tokyo press reported the arrival of Zenimura’s team in April:

The Fresno Japanese baseball team augmented by three American players reached Japan a few days ago and will make their first public appearance in Tokyo at the Meiji Shrine Field Tuesday afternoon when they lineup against the fast Meiji University nine. The visitors had a couple of nice workouts already and are raring to go. They are rapidly recovering from their long trip across the Ocean and should provide plenty of opposition against the local teams. One of their proudest records is that of defeating the Royal Giants who are now in Japan and cleaning up on the Japanese nine.

The Fresno team carries with them seventeen members including half a dozen pitchers so they are well supplied with plenty of reserve players in case of emergency. Hunt and Hendsch are two of their leading hurlers while Simons, the other American entry[,] will carry the bulk of the catching burden.

Manager Zenimura will probably handle the shortpatch himself and he needs no introduction to the Japanese sporting public for he made his initial bow a few years ago when the Fresno squad made their first trip here.26

The FAC received generous press coverage during their tour. Fans were provided with detailed information to get to know the Fresno pastimers:

Ken Zenimura, manager and shortstop[,] is the mainstay of the Fresno team. He has steered the team for the past several years through 4 successful seasons. Upon graduation from Mills High School in Honolulu in 1919, where he was captain, he went over to the mainland to join the Fresno Club and continue his higher education. While in Honolulu he was captain of the Asahi Ball Club. This is his second trip to Japan.

Captain Fred Yoshikawa, catcher, played for four years on the McKinley High School team in Honolulu. He captained the team through a series of games with Mills High which was headed by Manager Zenimura. He is a graduate of the Technical College of Kansas. This is his second trip to Japan.

Harvey Iwata, the left fielder, is a graduate of Fresno High, and is now making a special study of agricultural science. He was captain of the Fresno High team that won the Pacific Coast Championship in 1920. This is his second trip to Japan.

Ty Miyahara, third baseman, proud of the fact that he was received at the White House by President Coolidge last year. He made his first trip to Japan with the Honolulu Asahi team (in 1920). He also made a trip with the Fresno team in 1924. He studied at Center College, at Danville, Kentucky, where he played Center Varsity as a third baseman. At present he is a student at Columbia University.

Anthony Kunitomo, second baseman, joined the Fresno Club last year. He is attending Regis College at Denver, where he also played second baseman on the Varsity team. He has made his college team for the past three years.

Michael Nakano, first baseman, is attending college in Alameda, California. He was considered the best first baseman in the Japanese baseball league in 1926 on the coast.

John Nakagawa, centerfielder, is known in the states and here in Japan as the Japanese “Babe Ruth.” He pitched and played outfield for Fresno High, finishing there in 1926. This is his second trip to Japan.

Tandy Mimura, third baseman, is still in high school, attending Dinuba High. He made the highest batting average on his high school team last season.

Ken Furubayashi, outfielder, made his first trip to Japan in 1924. He pitched on his high school team Orosi High. On his last trip to Japan he was a Fresno pitcher but is now in the outfield, owing to his heavy hitting.

Samuel Yamasaki is the team’s leading batter and a third baseman, playing the same position now on the Fresno High School team. He will finish high school next year and he is the youngest member of the aggregation.

Richard Kawasaki pitched for both Los Angeles High School and a Japanese team in that city. He joined Fresno in 1926 as a member of the pitching staff.

James Hirokawa is on his second trip to Japan with Fresno, playing second base also for the Fresno State College.

Thomas Mamiya finished McKinley High School and has now joined Fresno to take up higher education in the states. He pitched for his high school and for the Asahi team and has the reputation of being the best Japanese pitcher in Hawaii.27

It’s worth noting that the three Caucasian ringers, Eldridge Hunt, Charlie Hendsch, and Jud Simons, are not detailed in the press.

The FAC won its first five games in Japan: two games against Keio, both by the score of 6-2, featuring future Japanese Hall of Famer Shinji Hamazaki; two games against Meiji, 10-5 and 6-0, against Hall of Famer Fujio Nakazawa; and a thrilling 10-inning, 3-2 victory over Hosei University.28

On April 20 the FAC and Lon Goodwin’s ballclub, now called the Philadelphia Royal Giants, met head-to-head in the newly constructed Meiji Jingu Stadium in Tokyo. Captain Zenimura shared his eagerness and excitement to play the upcoming game with Goodwin’s club with reporters.

The Fresno players, who have defeated the invading Royal Giants in America in baseball, will have the opportunity of demonstrating their superiority over the same nine when they cross bats in their first game in Japan on Friday afternoon at the Meiji Shrine [Jingu] Field. This match ought to attract a huge attendance as both teams have shown great strength in their contests against the local nines.29

According to Japanese baseball historian Kyoko Yoshida, Zenimura’s comments about previously defeating the Royal Giants caused quite a stir with several players, especially Biz Mackey, Rap Dixon, and Andy Cooper. They openly expressed their disappointment with the FAC, wondering why the Fresno players would lie to the media about previously beating them.30 More than 90 years later, we now see the historical misunderstanding that unfolded between Zenimura and the Negro Leaguers.

Based on his comments to the press, it appears that Zenimura was under the impression that the Negro League team he was scheduled to play in Tokyo was the same L.A. White Sox squad he had help defeat three times priorto the 1927 tour. Zeni was not aware that the Royal Giants team that boarded the ship in April was actually taken from two different rosters: Cooper, Dixon, Frank Duncan, O’Neal Pullen, and Mackey from Goodwin’s 1926-27 Royal Giants California Winter League team and select members of Goodwin’s 1926 semipro L.A. White Sox.

While the misunderstanding was unfortunate, it worked in favor of the Royal Giants. Biz Mackey channeled his anger into his bat, and more than 10,000 baseball fans at Meiji Jingu Stadium saw the future Hall of Famer singlehandedly defeat Fresno, 9-1.31 “Mackey, the star shortstop of his team, was the heaviest slugger of the day, getting three safeties on four official trips to the diamond, one being a four- ply wallop, and the other two, a three sacker and a double.” He was a single shy of hitting for the cycle.32

His historic home run, the first ever hit at Meiji Jingu Stadium, whistled through the air and landed in the center-field bleachers.33 The ball then rolled out of sight some hundred feet into a clump of trees.34

According to reports, the game was much closer than reflected by the final score. It was still anyone’s ballgame after the sixth inning, with a 2-0 score, but the Royal Giants “blew the lid off’ the game by scoring four runs in the seventh and then adding three more runs in the eighth. The FAC was able to get on the score board in the ninth inning thanks to a double by Jud Simons and an RBI single off future Hall of Famer Andy Cooper by pinch-hitter Sam Yamasaki.35

After the game it was reported that the Fresno Japanese would have a chance to “wreak their sweet revenge upon the boastful Colored nine” in a follow-up game scheduled for Friday.36 But the game was rained out and never rescheduled. For most players on both teams, they would have to wait until they returned to the United States for a rematch when the FAC battled the “Hilldale Royal Giants” (the CWL Philadelphia Royal Giants roster playing under a slightly modified team name) in March 1928 in Fresno.37

After the rained-out contest, each team went its separate way to play the best semipro, industrial, and college teams in Japan, China, Korea, and Hawaii. Both squads completed their respective tours with impressive winning records. The FAC finished with a 40-8-2 record, a solid .800 winning percentage. Playing against the same competition, the Philadelphia Royal Giants finished with a 35-2-1 record, an amazing .921 winning percentage.38

Perhaps more important than the wins and losses was the positive cross-cultural impact made by the tours. The Japanese players and fans were enamored with the Royal Giants, and the feeling was mutual. In Japan, both the Nikkei and Negro players found sanctuary from the racism they faced back in America. In the end, both teams were recognized by their Japanese hosts as true sportsmen and gracious ambassadors for the United States during the tour.39

After their games near Tokyo in April and May, the FAC team barnstormed a series of games in June in Hiroshima prefecture, Shikoku island, Hokkaido, Chosen (the Japanese name for Korea), and Manchuria (northeast China).40 In early August Zenimura and his men left Japan for an 11-game series on the Hawaiian islands. Highlights from Hawaii include

- A 4-2 victory over the All-Hawaiians, the undisputed leaders of the Hawaii league, at Honolulu Stadium, in which Zenimura stole home for the first run of the game.

- A 5-4 victory over the Honolulu Asahi. Kawasaki belted a home run, while Nakagawa closed the game to defeat future Japan Hall of Famer pitcher Bozo Wakabayashi.

- In a 10-4 victory over the Maui All-Japanese at Wailuku, Iwata went 3-for-4 with a home run, triple, single, and sacrifice. Defensively he recorded four putouts and one assist, and kept a home run from clearing the fence with his bare hand, holding the runner to a double.

After the last out of the final contest was logged on the Islands, the FAC boasted a 42-6-2 record in 50 games during their six-month tour.41

On September 6, Zenimura and his FAC teammates departed Honolulu and set sail for America on the passenger ship Taiyo Maru. Not on the return ship with the team were the three Caucasian ringers, Hunt, Hendsch, and Simons. The trio had returned home early in June, as they objected to the living conditions during the tour, wanted more money for their efforts once they saw the large crowds flocking to the games, and overall were unhappy during their time in Japan.42

The Fresno Bee announced the FAC’s return home on September 8. After spending half of 1927 touring across the Pacific, many of the team members opted to stay in San Francisco for some rest and relaxation. Captain Zenimura announced “that many offers for games again in the Orient were received by the club, and another trip probably will be made next year.”43

***

After the 1927 tour, another event involving Zenimura occurred that would greatly impact US-Japan baseball relations.

On October 29, 1927, Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig arrived in Fresno as part of their West Coast tour. Four Japanese Americans were selected to compete with Gehrig’s team: Zenimura, Iwata, Nakagawa, and Yoshikawa.44 Ruth wowed the fans with a mammoth home run, but it was not enough to overcome a 10-run deficit. The Bustin’ Babes lost 13-3 to the Larrupin’ Lous.45 After the game, Fresno-based photographer Frank Kamiyama captured a photo of Ruth and Gehrig towering over the four Nikkei players, in what would become one of the most visually striking and memorable photos in baseball history.

In addition to the game, a dinner was held at the Hotel Fresno to honor the two Yankees stars. During the event, it appears that Ruth and Zenimura discussed a tour to Asia and that the Babe asked him for assistance in arranging a tour to Japan.46

Several weeks after this historic encounter, Zenimura sent letters written on the back of copies of the Kamiyama photo to his Japanese contacts. They responded. “I got a call from Japan to see if I could get Ruth to go to the Island and play for a $40,000 guarantee,” said Zenimura. “I contacted Ruth and he said he would go for $60,000. It was too much but a few years later he went and made a big hit.”47

In 2017 a copy of one of Zenimura’s letters sent in November 1927 was discovered by Dr. Masaki Yoshikatsu, curator of the Hankyu Culture Foundation in Osaka. Zenimura’s message was buried in the archives as part of a photo collection donated by the family of Masaru Kataoka, former executive with Daimai (Osaka Mainichi newspaper). Kataoka was also once a member of the Nihon Undo Kyokai (Shibaura Association), Japan’s first pro team, which disbanded after the 1923 Tokyo earthquake, and reorganized as the Takarazuka Athletic Club.48 In 1921 the Nihon Undo Kyokai loaned him to the Sherman Indians team during their tour of Japan.

The back of the photo contained the following hand-written message from Zenimura (now known as the “Kataoka Letter”):

This picture was taken at Fresno when Babe Ruth and Gehrig of the New York Yankees visited us on October 29th. We played against them and made a wide reputation for our team.

Babe Ruth is interested to visit Japan and has asked me to try and line up things in Japan so that he may be able to come to Japan with our team. I wrote to the Meiji University asking them to what extent they can offer to have Babe Ruth in Japan. I believe that it will draw to have Babe Ruth in Japan.

I am sending this picture to you so that you may have this picture in your leading page. It’s my remembrance to you. Kindly extend my best wishes to all of your players. Hoping to meet you again in Japan.

I am yours truly,

K. Zenimura

The discovery of the Kataoka Letter documenting Zenimura’s efforts to negotiate a tour for Babe Ruth to Japan corroborates Zeni’s 1962 Fresno Bee interview, and further solidifies his role as an important ambassador of US-Japanese baseball relations.

THE 1937 TOUR

Harry Kono, Alameda florist, baseball enthusiast, and close friend of Zenimura’s, made a name for himself in 1936 serving as a scout for Dai Tokyo of the fledgling Japanese Baseball League, when he signed pitcher James Bonner, the first African American to play in Japan.49

On February 12, 1937, the Hayward Daily Review announced that Kono was making the final plans to take a ballclub to Japan. The team had already received financial guarantees from Tokyo managers and sailing was set for March.50 Eight Fresno players were included in the Kono Alameda All-Star team, which departed in March on the Chichibu Maru from San Francisco, bound for Honolulu to begin a 42-game schedule.51 The 20 men on the roster included: Harry Kono, manager; Ken Zenimura, business manager and coach/player (second base, catcher); Kenso Nushida, assistant coach; pitchers Shig Tokumoto, Masa Yano, Paul Allison, and Marion Alleruzo; and position players Noboru Takagi, Wilson Ishida, Norman Riggs, Ty Shirachi, Charles Davis, Tut Iwahashi, Frank Mirikitani, Charles Hiramatsu, Kiyo Nogami, Ky Miyamoto, A1 Sadamune, and Frank Yamada.52

With plenty of time to pass on the 18-day journey from California to Japan, Zenimura wrote the following letter, dated March 17, 1937, to Fresno Bee sports editor Ed Orman:

Tomorrow we will arrive in the Land of the Rising Sun—Japan. It is reported that on the same day as our arrival, Prince Chichibu is sailing for Seattle and later will pass through Canada en route to attend the coronation in England. The entire battle fleet will guard the ship on which Prince Chichibu is sailing and I can imagine that the sendoff will be a great one. We are lucky to be on hand to witness the sight from the Yokohama Bay on Chichibu Maru.

I cannot write about Japan yet so I will drop you a line to let the Fresno fans know about Honolulu. The ship was delayed in reaching the islands due to a heavy storm that lasted for two days. Instead of arriving around 8 A.M. we finally reached port atll:30 A.M. When the ship made headway toward the pier, the famous Hawaiian Band played “California, Here I Come” and many other popular songs. The sports editors of various papers met us and placed leis of flowers around our necks, meaning Welcome to the Paradise.

After taking several pictures of the team we were all invited for a short sightseeing trip. Jimmy Hirokawa, one-time Fresno State baseball player who played with the college in 1922 and 1923, was there and arranged for five automobiles for the players to drive on the sightseeing trip. …

We came back to the ship and dressed in baseball uniforms and rushed to the park to play against the Asahi. For four innings we played a swell game, but after Kunihisa scored by stealing home the players became excited and blew up. Our team made eight errors during six innings, The final score was 10-to-0. It was a good workout for the players. We will win most of our games in Japan. If I should fail in Tokyo, I will be taking the next ship back to the states.

Paul Allison and Marion Alleruzo both are enjoying the voyage but I expect to see them make good in Japan. Both are working out every morning and they seem to be in shape. I probably will start Alleruzo in the first game in Japan. In Honolulu I signed another pitcher, Ed Suzuki, the best Japanese pitcher in the islands. This boy no doubt will win most of the games with his speed. I made a quick decision to take the pitcher and I believe that I made a wise move.

This morning I received a wire from Manila stating they want us to play eight games there. The Warner & Barnes Company, Ltd., is trying to promote the games. I have written to them stating my terms. If they are suitable I probably will divide the team into two squads and take twelve players to Manila.

I will let you know later about this. If we do go we probably will play one game in Shanghai and another in Hong Kong in China before arriving in Manila. I will ask Paul Allison to write to you about his ideas on the voyage and if he does kindly publish it in your paper. I will write to you from Yokohama, giving you the results of the four games we play there.

Thanks for the space given us in your sports page. Please extend our best regards to all the American baseball fans in Fresno.

Sincerely yours, KEN ZENIMURA

Coach, Kono All-Stars53

The Kono Alameda All-Stars returned home on July 15, after notching a 41-20-1 record in Asia. Game results were not published; however, what we lack in quantitative details is made up with a wealth of qualitative information shared by Zenimura after the tour. An article published by the Fresno Bee in Ed Orman’s Sport Thinks column captures Zeni’s rich experiences, insight, and perspectives on baseball in Japan in 1937:

Kenny Zenimura, Fresno’s leading Japanese exponent of the great American national pastime of baseball, is back home after a sojourn in his native land, and the popular little baseball man has a bag full of interesting tales about Japan.

Being sports minded, Kenny paid more attention to things athletic in the land of the rising sun, and particularly his sport—baseball. The Nipponese, believes Zenimura, have improved in baseball proficiency at least 100 percent within the last decade. It was in 1927 that Zenimura took a squad of ball players, American and Japanese, to Japan for a barnstorming trip. Baseball then was just beginning to sprout wings in that country, but today it is vastly different.

“Baseball has blossomed into THE sport in Japan now and the Japanese can play ball which compares favorably with the brand played in America,” related Zenimura. “I was agreeably surprised. Ten years ago the Japanese did not know the scientific points of playing. Today they know as much as we do in this country, or just about, at the least. Where they used to be weak hitters, the Japanese now can hit them hard and far. I saw many home runs inside of parks with fences some 420 feet from the plate.”

Zenny, now a West Fresno automobile dealer, noted the new generation of Japanese people is larger in stature and for that reason the young ball players get more power at the plate. Always noted as fancy and fast fielders and base runners, the Japanese now are only coming into their own as distance hitters.54

Although Zenimura was engaged as coach for the tour, when he reached Japan he was surprised to discover that he was “barred on the diamond on the pretense of being a professional” and it was a month before he could help out his squad. As result, the team lost many games during his absence from the field.55

Wasting no time in Japan, when pushed to the sidelines Zenimura was also engaged as a scout for teams playing in a professional league around Tokyo and for a Honolulu team. His international baseball contacts encouraged him to send talented California ballplayers to Hawaii and Japan.56

In fact, four players stayed behind to play professional baseball in Asia: Tut Iwahashi and Shiro Kawakami signed with the Dairen Gitsugyo team in Manchuria; while Kiyo Nagami and Frank “Den” Yamada joined Hankyu Shokugyo in the fledgling Japanese Professional Baseball League.57

***

Upon returning home from the 1937 tour, Zenimura immediately shifted focus to plans to take a team to Tokyo for an amateur baseball competition associated with the 1940 Olympic Games. He reserved more than 60 rooms in a Tokyo hotel to accommodate his travel party.58 The Games were canceled in July 1938 due to the war between China and Japan.59 The news was a disappointment to Zenimura, the first of many leading up to one of the darkest chapters in US history -the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Just as he had done before the war, while behind barbed wire at Gila River, Arizona—one of 10 camps constructed by the US government to incarcerate approximately 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry between 1942 and 1945—Zenimura used the game of baseball to break down barriers, bond communities, and bring joy to the lives of others. After the war, he continued to play, manage, scout, and help others coordinate tours to Hawaii and Japan.60 Zeni continued to scout and connect talent with Japanese teams. His two sons, Kenshi and Kenso, were among the first Americans to play for the Hiroshima Carp, in 1953.61 Zeni also arranged for outfielder Satoshi “Fibber” Hirayama, a California native and multisport athlete to play in Japan, where he went on to enjoy a 10-year all-star career (1955-1964) with Hiroshima. When Zenimura died in 1968, Fibber delivered his eulogy. “The reason I was able to go to Japan and have a great career was because of Mr. Zenimura’s faith in me,” Hirayama later remarked.62

***

During his lifetime, Zenimura played a major role in helping to construct “Baseball’s Bridge Across the Pacific.” The ballplayers who cross that bridge—in both directions—are indebted to him and other Nikkei baseball pioneers who worked tirelessly to build it. In fact, Zenimura’s lifelong friend and tour counterpart in Japan, Takizo “Frank” Matsumoto, was inducted into the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame in 2016 for similar work on that side of the Pacific.63

With this in mind, multiple requests have been made to officials in Cooperstown asking for Nikkei baseball and “The Father of Japanese American Baseball” to be properly honored in the National Baseball Hall of Fame with a permanent presence equal to what is currently in place for other historically marginalized ballplayers (i.e. Negro Leaguers, Latinos, and women).64 Since the early 2000s, these requests have fallen on deaf ears.

In 2018, the Baseball Writers Association of America enthusiastically accepted Zenimura’s nomination for inclusion on the highly anticipated Early Baseball Era ballot. They responded, “[B]e assured Mr. Zenimura will be given appropriate consideration.”65 Despite Zeni’s meeting all the criteria for Early Baseball Era consideration and his impressive resume as a global baseball ambassador, the committee members assembled by the Hall of Fame failed to give his nomination “appropriate consideration.”66 In fact, despite the enthusiastic assurance from the BBWAA, Zenimura’s nomination was not even discussed.67

Instead, the only aspect of Zenimura’s legacy embraced by the Hall of Fame today is his handmade wooden home plate from the wartime incarceration camp at Gila River, Arizona.68

When the wooden object was initially included in the Hall of Fame’s traveling exhibit “Baseball as America” in 2002, it was considered a “riveting” artifact that helped “tell the honest story of baseball.”69 Who knows, perhaps it still does? But maybe it also teaches us that baseball’s “honest story” is still evolving.

For example, with the alarming increase in anti-Asian attitudes and hate crimes stemming from the COVID pandemic, the Hall of Fame’s decision to only display an artifact created by a Japanese American incarcerated behind barbed wire now smacks of tokenism, and is indicative of the systemic racism that still exists in baseball’s power structure today. Zenimura’s home plate, devoid of the larger story and legacy of Nikkei baseball, has now become a symbolic reminder of the ongoing marginalization of people of Asian ancestry in the United States—and of the work that remains to achieve true diversity, equity, and inclusion in America—and in baseball.70

Perhaps this too is part of Kenichi Zenimura’s legacy. Only time will tell.

BILL STAPLES JR. of Chandler, Arizona, a SABR member since 2006, has a passion for researching and telling the untold stories of the “international pastime.” His areas of expertise include Japanese-American and Negro Leagues baseball history as a context for exploring the themes of civil rights, cross-cultural relations, and globalization. He is a board member of the Nisei Baseball Research Project and the Japanese American Citizens League-Arizona Chapter, chairman of the SABR Asian Baseball Committee, and research contributor to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. Staples is the author of Kenichi Zenimura, Japanese American Baseball Pioneer (McFarland, 2011), and co-authored Gentle Black Giants: A History of Negro Leaguers in Japan (NBRP Press, 2019) with Japanese baseball historian Kazuo Sayama. He has contributed to numerous articles and news stories for global media including MLB.com, Sports Illustrated, NPR, the Japan Times, Kyodo News, TV Asahi, and NHK. His other SABR publications include articles in Baltimore Baseball (2021), One-Hit Wonders (2021), and No-Hitters (2017). He received the SABR Baseball Research Award in 2012 for the Zenimura biography and in 2020 for the article “Early Baseball Encounters in the West: The Yeddo Royal Japanese Troupe Play Ball in America, 1872.” Learn more at zenimura.com.

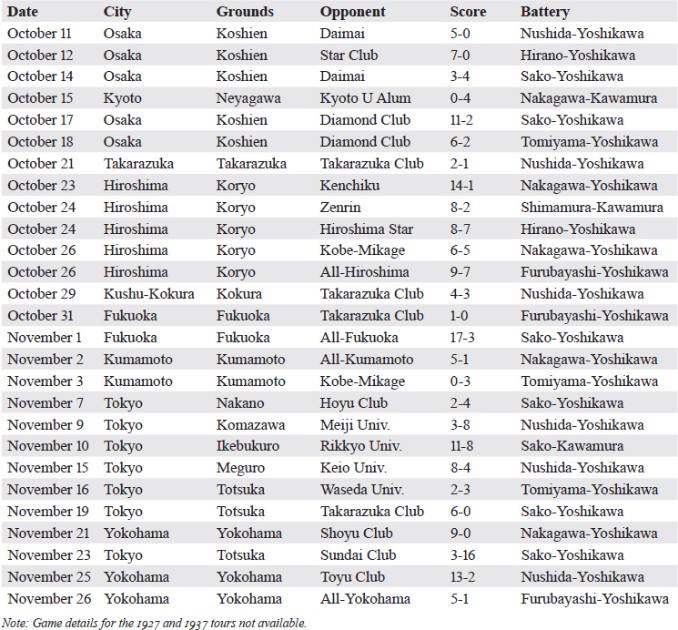

1924 FRESNO ATHLETIC CLUB GAMES IN JAPAN

During their 27-game tour of Japan in late 1924, Zenimura’s Fresno Athletic Club finished with a 20-7 record (.741 winning percentage).

NOTES

1 “Future Eligibles, 2025,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, www.baseballhall.org/hall-0f-famers/future-eligibles#2025-eligibles.

2 Bill Staples Jr., Kenichi Zenimura, Japanese American Baseball Pioneer (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2011), 3-7.

3 In 1928 Ty Cobb toured Japan a couple of months after his retirement with Bob Skawkey and Fred Hoffmann, but not as part of an organized team. “Ty Cobb Will Tour Japan for Baseball,” Arizona Daily Star (Tucson), October 10, 1928: 4.

4 Tom Meehan, “Fresno’s Ken Zenimura, Dean of Nisei Baseball in US, Recalls Colorful Past,” Fresno Bee, May 20, 1962: 8-S.

5 Ed Orman, “Zenimura, Dean of the Diamond,” Fresno Bee, August 2, 1970: 3-B.

6 Jeff Davis, “A Slice of Japanese Americana,” Fresno , May 3, 1996: D1.

7 Kazuo Sayama and Bill Staples Jr., Gentle Black Giants: A History of Negro Leaguers in Japan (Fresno, California: Nisei Baseball Research Project Press, 2019), 176-180.

8 “Playing and Talking about Baseball Across the Pacific,” Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/webcast-8949, 39:40 mark.

9 “Playing and Talking about Baseball Across the Pacific.”

10 “Japanese Clubs to Play Series Here for Title,” Fresno , July 3, 1923: 4.

11 “Fresno Japanese Win Championship from Seattle Club,” Fresno Bee, July 5, 1923: 12.

12 F.H. Vore, “Japanese Win from Bees 6 to 4,” Fresno , March 10, 1924: 4.

13 W.S. Tyler, “Bees Wallop Japanese 15-2,” Fresno Bee, March 31, 1924: 4.

14 Brian McKenna, “Lefty O’Doul,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/lefty-odoul/.

15 Associated Press, “Fresno Japs Will Invade the Orient” Los Angeles Times, July 18, 1924: 11.

16 “Nippon Ball Tour of Fresno Highly Successful,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, December 11, 1924: 12.

17 “Nippon Ball Tour of Fresno Highly Successful.”

18 Meehan.

19 “F.A.C. Team Wins in Japan,” Fresno Morning Republican, December 5, 1924: 19.

20 Kerry Yo Nakagawa, Through a Diamond: 100 Years American Baseball (San Francisco: Rudi Publishing, 2001), 18-19.

21 “Star Jap Nine to Play Series Here,” Los Angeles Times, September 6, 1925: 1a, 8.

22 “Fresno, 5; White Sox, 4,” Los Angeles Times, September 7, 1925: 13.

23 “Fresno All-Stars Win Again from L.A. Team, 4 to Fresno Bee, July 6, 1926: 10.

24 “Negro Baseball Team to Japan,” Nippu Jiji, December 21, 1926: 10.

25 “Japanese Ball Club to Invade Orient Again,” Fresno Bee, January4, 1927: 10.

26 “Fresno Japanese Nine to Play Meiji in 1st Game,” Japan Times, April 5, 1927: 8.

27 “Fresno Combine Arrives to Play Local Tossers,” unknown Honolulu paper, August 2, 1927, from the Harvey Iwata 1927 Tour Scrapbook, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

28 Harvey Iwata 1927 Tour Scrapbook, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

29 “Fresno Japanese Plays Basketball 1st Game April 20,” Japan Times, April 15, 1927: 8.

30 Email correspondence with Kyoko Yoshida, 2007.

31 “Royal Giants Swamp Fresno Japanese 9-1,” Times, April 22, 1927: 8.

32 “Royal Giants Swamp Fresno Japanese 9-1.”

33 “Royal Giants Swamp Fresno Japanese 9-1.”

34 “Royal Giants Swamp Fresno Japanese 9-1.”

35 “Royal Giants Swamp Fresno Japanese 9-1.”

36 “Royal Giants Swamp Fresno Japanese 9-1.”

37 Frank Irwin, “Hubbard Leads Giant Team in Busy Session,” Fresno Morning Republican, March 19, 1928: 7.

38 Stephen Ellsesser, “Black Giants Were Treated Like Royalty,” MLB.com, February 23, 2007.

39 “Royal Giants Won 26, Tied One on Their Japanese Tour,” Chicago Defender, June 25, 1927: 9.

40 From the Harvey Iwata 1927 Tour Scrapbook, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

41 Jane Leavy, The Big Fella: Babe Ruth and the World He Created (New York: Harper, 2018), 400.

42 >”Firemen Ready to Meet Calpets This Afternoon,” Fresno Bee, June 12, 1927: D1.

43 “Fresno Baseball Club Back from Orient,” Fresno Bee, September 8, 1927: 12.

44 “Plans Progress for Ruth-Gehrig Game in Fresno,” Fresno Bee, October 18, 1927: 15.

45 Ed W. Orman, “Fans Pack Park to Watch Ruth Gehrig Perform,” Fresno Bee, October 29, 1927: 7; Ed W. Orman, “Babe Ruth Hits Homer to Thrill Crowd of 5,000,” Fresno Bee, October 30, 1927: 1D.

46 Kataoka letter, shared with the author by Masaki Yoshikatsu, curator of the Hankyu Culture Foundation, Osaka, Japan, 2018.

47 Meehan.

48 Kataoka letter.

49 Ralph Pearce, James Bonner Biography entry, Gentle Black Giants: A History of Negro Leaguers in Japan, 211-219.

50 “Local Pitcher to Make Japan Tour,” Hayward (California) Daily Review, February 12, 1937: 3.

51 “Fresno Players Will Sail for Japan Tonight,” Fresno Bee, March 2, 1937: 3B.

52 “Fresno Players Will Sail for Japan Tonight.”

53 “Zenimura Writes About Trip of Baseball Club,” Fresno Bee, April 6, 1937: 2-3-B.

54 Ed W. Orman, “Sport Thinks,” Fresno Bee, August 11, 1937: 2-B.

55 Orman, “Sport Thinks.”

56 Orman, “Sport Thinks.”

57 Nakagawa, 65.

58 Orman, “Sport Thinks.”

59 John Findling et al., Encyclopedia of the Modern Olympic Movement (Santa Barbara, California: GreenwoodPublishing Group, 2004), 120.

60 Meehan.

61 “Zenimura Boys to Play with Japan Team,” Honolulu Advertiser, June 14, 1953: Sec 3, 10.

62 Documentary: Diamonds in the Rough: Zeni and the Legacy of Japanese- American Baseball (Chip Taylor Communications, 2004), 22.

63 Takizo Matsumoto entry, Baseball-Reference.com, https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Takizo_Matsumoto.

64 Gregory Lamb, “Backstory: The Players in the Shadows.” Christian Science Monitor, June 29, 2006, www.csm0nit0r.c0m/2006/0629/p20s01-alsp.html.

65 Email correspondence with BBWAA leadership, October 2018.

66 Shanthi Sepe-Chepuru, “Negro Leagues Players Up for Hall Review.” MLB.com, October 23, 2021, www.mlb.com/news/hall-of-fame-considering-negro-leagues-players-for-induction.

67 Email correspondence with voting members of the Early Era Committee, December 2021.

68 Alex Coffey, “A Field of Dreams in the Arizona Desert.” National Baseball Hall of Fame, https://baseballhall.org/discover/a-field-of-dreams-in-the-arizona-desert.

69 Josh Getlin, “Trade Centre Balls among Exhibit,” Edmonton (Alberta) Journal, April 1, 2002: D2.

70 Email correspondence with Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) leadership, April 22, 2021.

71 Asahi Sports, No. 32-34, 1924, 1 Japan (compiled and shared by Kyoko Yoshida); and “Nippon Ball Tour of Fresno Club Highly Successful,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, December 11, 1924: 12.