Land of the Free, Home of the Brave: Mudcat Grant’s Odyssey to Sing the National Anthem

This article was written by Dan VanDeMortel

This article was published in The National Pastime: Steel City Stories (Pittsburgh, 2018)

When San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick refused to stand for the national anthem during a 2016 preseason game to protest police violence against black people in America, all hell broke loose. Voices of praise and condemnation rained down. Passion often trumped reason. The “conversation” remains heated, while complicated criminal justice problems remain unsolved.

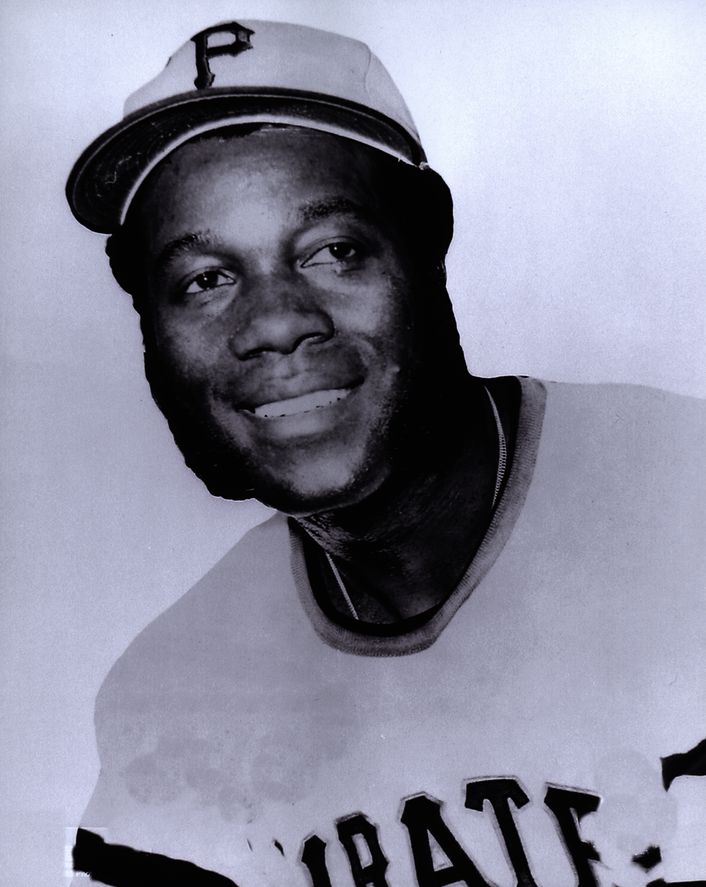

Is there a way for collectively honoring a song that symbolizes Home while Home leaves some citizens vulnerable with little political or legal recourse? Football and basketball players, owners, and fans have struggled to find that balance. Meanwhile, baseball remains cloaked in timidity, virtually silent in words and deeds on the field and off.1 Its fans are thus left to a difficult search through history for any semblance of a clue or role model. Yet relevant history does exist: October 4, 1970, at newly opened Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh, when, moments before the Pirates hosted the Cincinnati Reds in National League Championship Series Game Two, black Pirates relief pitcher James “Mudcat” Grant — sporting muttonchop sideburns and an immaculate white pin-striped suit — took the microphone to sing the anthem.

Is there a way for collectively honoring a song that symbolizes Home while Home leaves some citizens vulnerable with little political or legal recourse? Football and basketball players, owners, and fans have struggled to find that balance. Meanwhile, baseball remains cloaked in timidity, virtually silent in words and deeds on the field and off.1 Its fans are thus left to a difficult search through history for any semblance of a clue or role model. Yet relevant history does exist: October 4, 1970, at newly opened Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh, when, moments before the Pirates hosted the Cincinnati Reds in National League Championship Series Game Two, black Pirates relief pitcher James “Mudcat” Grant — sporting muttonchop sideburns and an immaculate white pin-striped suit — took the microphone to sing the anthem.

Why was Grant singing the anthem? And how is that relevant today? The answers offer insight into a unique blend of accomplishment in both baseball and singing, both while navigating our country’s civil rights struggles.

Grant was born in 1935 in Lacoochee, Florida, a rural lumber-mill town north of Tampa. Just two when his father died, James and his five siblings were raised by their mother, who worked at a citrus canning factory and as a domestic worker. Excelling at sports, James eventually competed with a semipro team, which stationed him at third base. He earned an athletic scholarship to Florida A&M University but soon left due to family financial hardships. Baseball fortuitously offered rescue in 1954, when bird-dog scout Fred Merkle, having previously watched Grant in high school, invited him to a Daytona Beach tryout with the Cleveland Indians. Once there, Grant’s black skin and ragged uniform prompted a fellow invitee to haze him with the nickname “Mudcat,” claiming he was as ugly as a Mississippi catfish. The nickname stuck; a “brand” was born. Impressed with his live arm, and seeing his potential as a pitcher, the Tribe signed “Mudcat” days later.

In essence, a happy ending. But, harsher truths abounded, challenging Grant’s Baptist upbringing. His family’s dilapidated shack lacked electricity, hot water, and toilets. He studied from shabby schoolbooks, disdainfully discarded from white schools, by kerosene lamp or firelight. His mother once collapsed from exhaustion, falling on the stove and burning her face and arms. To help, the teenage Grant lied about his age to gain work in the lumber mill.

Even worse, segregation provided constant intimidation and danger. The family had a trapdoor in the floor, a refuge for when marauding white bands invaded, shooting into houses during what Grant described as “n*****-shooting time.”2 He was verbally and physically harassed by local authorities, and whites pelted him with rocks when he ventured outside “colored” areas. A childhood friend was killed for violating racial protocol.3 As Grant recalled, “As a black person, if you tried to think about the worst thing that could happen to you, it could happen that day. And something worse could happen to you the next day. . . . These became almost everyday things. . . . We were terrorized for 300 years. But we didn’t call it terror.”4

Two women kept Grant focused. His mother, a church choir director, instilled a religious belief that he could succeed, that he had “come into the world for many missions.”5 She helped forge the endurance needed to handle racism and encouraged him to release anger in an unharmful way. Inspiration also came from teacher Vera Lucas Goodwin, a woman of culture and music in barren circumstances. She found in Grant a talented spirit: a “bathtub singer” since his mother taught him at five. Grant eagerly devoured her knowledge and recordings of Johann Strauss, Eddy Arnold, John Lee Hooker, and others she passed along.6

Grant graduated to the Indians in 1958, where he became the American League’s only black starting pitcher. “You were always aware of the fact that you were black because there were stares, there were people that took your money at the counter [who] didn’t want to touch your hand,” he wrote, adding, “Pain always showed up, every day, in terms of something that happened.”7

1960 offered two dramatic opportunities to deal with the pain. On September 5, his Detroit hotel phone rang in the morning. An aide for presidential candidate John F. Kennedy said Kennedy wanted to meet him for breakfast. Grant hung up, figuring the call a prank. Minutes later, though, Kennedy’s aides appeared at his door, and soon he was having breakfast with the Massachusetts senator. They talked for an hour, covering baseball and Kennedy’s admiration for him and the sport’s black pioneers. But Grant also kept it real, covering his upbringing, both good and ill. Their conversation springboarded Grant to a future White House meeting, where Grant asked for and received aid for Lacoochee.

Eleven days later in Cleveland, opportunity took a darker turn. Egged on by bullpen teammates and frustrated by obstructed efforts to integrate Southern lunch counters, Grant’s tolerance boiled over as he sang along with the anthem. As the song reached its ascending conclusion, Grant ad-libbed, “And this land is not so free, ’cause I can’t even go to Mississipp-ee,” or words to that effect.8 Pitching coach and Texas resident Ted Wilks overheard. “If you don’t like our country, why in the hell don’t you get out,” he thundered. “Well, I can get out of the country,” Grant replied. “All I have to do is go to Texas. That’s worse than Russia.” Wilks lit the match: “Well, if we catch your black n***** ass in Texas, we’re going to hang you from the nearest tree.”9 Grant threw a punch that dropped Wilks to the ground. Pushing and shoving ensued until teammates separated them. Angered and unable to think clearly, Grant fled the park without alerting manager Jimmy Dykes, for which he was suspended for the rest of the season.

Some accounts indicate Wilks apologized. “Are you kidding me?” Grant recently scoffed. “He was a racist. . . . There was no way he was going to apologize because [racism] was too strong back in those days.”10 To the team’s credit, it quickly reassigned Wilks to the minor leagues and kept Grant on.11 But letters filled his mailbox, some complimentary, many not. He burned all but one he considered “funny” from a war veteran: “Dear black SOB, you got a lot of nerve,” it read. “After all we’ve done for you. . . . We ought to ship all you N****** and Jews back to Africa.”12 Grant expected other players to follow his protest, but no one did.

Over time, unlike Kaepernick, Grant’s career thrived, especially after he completed Army duty in 1962. He developed a sinker, “Comet Ball,” “fast curve,” “Hop and a Jumper,” and a discussed-but-never-thrown “Cloud Ball that got a little wet from the air”/“razzafratz”/“soapball” spitball.13 Everything climaxed in 1965, after he was traded to the Minnesota Twins and became the first black American Leaguer to lead the league in wins, shutouts, and winning percentage.

Another career also blossomed: entertainment. Using presentation skills forged at baseball community-relations events, Grant pursued a singing career, debuting in 1962 at a benefit banquet. That led to more appearances, solo and with assorted groups, where he pleased fans with autographed pictures and handouts of his poem “Life,” which compared life to baseball.14

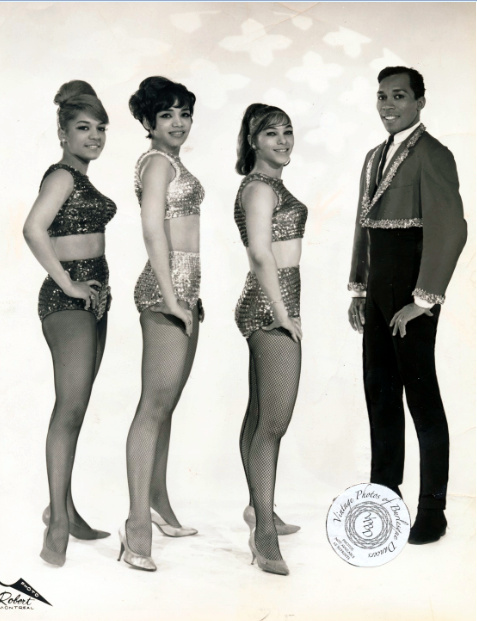

His baseball success in 1965 rocketed Grant’s music act to the big leagues, highlighted by appearances on Johnny Carson’s and Mike Douglas’s television shows.15 Influenced by Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie, and others, Grant formed Mudcat and the Kittens. The group focused on blues, with touches of R&B, jazz, pop, soul, gospel, and pure showbiz. Grant contributed fame, a melodious baritone voice, sartorial perfection that could make a tuxedo cat smile, a dancer’s grace, and an ability to read an audience like nobody’s business. The Kittens brought groove. A choreographer, drummer, guitar player, and bass player joined a group of sexily clad female “Kittens” — all accomplished church singers with curves and harmony.

His baseball success in 1965 rocketed Grant’s music act to the big leagues, highlighted by appearances on Johnny Carson’s and Mike Douglas’s television shows.15 Influenced by Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie, and others, Grant formed Mudcat and the Kittens. The group focused on blues, with touches of R&B, jazz, pop, soul, gospel, and pure showbiz. Grant contributed fame, a melodious baritone voice, sartorial perfection that could make a tuxedo cat smile, a dancer’s grace, and an ability to read an audience like nobody’s business. The Kittens brought groove. A choreographer, drummer, guitar player, and bass player joined a group of sexily clad female “Kittens” — all accomplished church singers with curves and harmony.

The group’s work ethic was pure baseball. “It was like baseball: The more you practiced the better you got at it. You had to rehearse or it would be like going on the field with nine players who had never played with each other,” Grant explained.16 Attending sessions of and receiving feedback from legends such as Marvin Gaye and Gladys Knight and the Pips, the band honed its craft until magic happened: “the time of night when everybody had a few drinks and thought maybe we were Sinatra!”17 With or without Kittens, Grant performed nationwide, in Canada, Europe, and the Caribbean, and three times joined fellow baseball players on goodwill tours of Vietnam.

As the 1960s wore on, though, Grant continued to confront racial impediments. His skin limited endorsement possibilities open to baseball’s white stars. Gradually embroiled in the Twins’ increasing racial divisions and embittered by acrimonious contract negotiations, Grant was traded after the 1967 season. “My mind was so perverted. I was crawling with hate,” he later reflected.18 For two years, he drifted from team to team, relegated to the bullpen while struggling with age and injuries. He flirted with racial danger by attending civil rights rallies and sneaking encounters with a white Austrian woman, which did not fly well with white team owners.19 His singing career, although busy, no longer commanded the national spotlight. Meanwhile, the country also struggled. His acquaintances and idols Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy were assassinated. And American strife went global at the 1968 Olympics when two black track medalists raised gloved fists in a Black Power salute as the U.S. national anthem played during the medals ceremony.

Landing with the Oakland A’s in 1970 resuscitated Grant, who became a relief specialist, racking up 80 appearances, 24 saves, and a 1.82 ERA for the season with Oakland and, late in the year, Pittsburgh.20 Performance-wise, as one of the two players chosen to represent the A’s, he sang the anthem soul style and played in a March 28 exhibition all-star game at Dodger Stadium to benefit King-related causes.21 Days later, A’s owner Charlie Finley, who was open to any promotional event, appointed Grant to sing the anthem, in uniform, on Opening Day, the first time a participating player had been so honored in any regular-season game.22

When the A’s pennant hopes dwindled in August, they traded Grant to the contending Pirates.23 Although he was upset with another address change, once he focused forward, he sang a different tune, fitting in like a glove, or more like a musical ambassador. “In the clubhouse they always wanted me to perform. I went ahead and did that, at no charge,” he quipped.24 On the road, Grant escorted teammates, including Roberto Clemente and Manny Sanguillen, to landmarks such as the Apollo Theater in New York, where baseball was revered. The musicians “would get taking pictures with the Pirates and before you know it, you’ve got 10 to 15 people that want their pictures taken with my teammates. You’d have more people watching the ballplayers than the performers!”25 And for extra laughs, Grant roomed with star pitcher Dock Ellis.26

Grant helped the Bucs win the NL’s Eastern Division, but his late arrival prohibited playoff participation.27 Game Two brought a chance to shine when General Manager Joe L. Brown asked him to sing the anthem. Grant immediately accepted, troubled past notwithstanding. “I would never have sung it publicly in a protest circumstance where it would be used for anything other than the anthem,” he said years later.28 His nationally televised semi-rock rendition — backed by organ, trap drum, and trombone — before 39,317 fans marked the first time a participating team’s player sang the anthem before a playoff game.29 Inexcusably, the only notable “analysis” of this milestone came in the form of a Tampa Tribune columnist writing that Wilks, by not forgiving or forgetting Grant’s 1960 rendition of the anthem, “helped Grant learn a lesson.30 That’s fake news.

Grant helped the Bucs win the NL’s Eastern Division, but his late arrival prohibited playoff participation.27 Game Two brought a chance to shine when General Manager Joe L. Brown asked him to sing the anthem. Grant immediately accepted, troubled past notwithstanding. “I would never have sung it publicly in a protest circumstance where it would be used for anything other than the anthem,” he said years later.28 His nationally televised semi-rock rendition — backed by organ, trap drum, and trombone — before 39,317 fans marked the first time a participating team’s player sang the anthem before a playoff game.29 Inexcusably, the only notable “analysis” of this milestone came in the form of a Tampa Tribune columnist writing that Wilks, by not forgiving or forgetting Grant’s 1960 rendition of the anthem, “helped Grant learn a lesson.30 That’s fake news.

1971 brought the debut of mentor Marvin Gaye’s classic “What’s Going On” album, which lamented “trigger happy policing,” among other societal problems. Grant remained a popular Pirate, entertaining a Pirates Wives team-packaged event in Pittsburgh and a teen-night crowd in St. Louis before a game. But his pitching slipped, so in August he was ping-ponged back to the A’s. “Baseball is a business. Maybe I’m just another one of its saleable items,” he said with resignation.31

Recording three saves and a win, Grant pushed the A’s to the League Championship Series. When Oakland returned home for Game Three after losing the first two to the Orioles in Baltimore, Finley once more selected Grant to sing the national anthem, which he did before 33,176 fans. His “slow, Billy Eckstine” voice could not prevent another loss, however, freeing him for the Kittens and the running of Mudcat Incorporated, a cosmetic company specializing in, appropriately, Mud for Cats complexion cream.32

The A’s released Grant the following spring. His efforts to return to the majors failed. “Baseball players are like streetcars: They just come and go,” Grant once remarked, and his career was quickly gone.33

Grant soon broke up the Kittens to focus on solo gigs. Since his retirement as a player, he has held various positions inside and outside baseball and has sung the anthem repeatedly, including at Frank Robinson’s color barrier-breaking managerial debut in 1975. In 2007, he authored The Black Aces — a profile of baseball’s black 20-game winners — and was honored with black leaders at the White House, where President George W. Bush commended his “courage, character, and perseverance.”34 Free of past anger, his mission remains true: “Feel the pulse of your community and see what you can do to alleviate some of the problems that have been tagging us for a long time.”35

When asked recently about Kaepernick’s protest, which he supports, Grant said, “Racism gnaws at your guts. You either want to say something or you don’t want to say anything. And one morning you wake up and say, ‘I gotta say something.’ But some people will understand it and some people won’t. But you sure are going to catch hell because some people don’t want to hear it.”36 Making such a choice in the public eye is indeed difficult, with Grant the closest embodiment baseball has to straddling the line where sports, social justice, speaking out, and patriotism intersect.

DAN VanDeMORTEL became a Giants fan in Upstate New York and moved to San Francisco to follow the team more closely. He has written extensively on Northern Ireland political and legal affairs, and his Giants-related writing has appeared in San Francisco’s “Nob Hill Gazette” and SABR’s “The National Pastime.” An investigation into the shooting of a fan at the Polo Grounds will appear in a Polo Grounds anthology to be published in 2018. He is currently researching and writing articles on the 1971 Giants and their time period. Feedback is welcome at giants1971@yahoo.com.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to James “Mudcat” Grant for granting an interview to discuss his singing and baseball career. A tip of the cap goes to the Hall of Fame staff for research assistance and to Ken Manyin, Ryan McEwan, and Kyla Gibboney for helpful editing. Truly missed while working on this article was the presence of Greg Erion (1947–2017), longtime SABR author, editor, organizer, and mentor extraordinaire.

Notes

1 Few baseball players have commented on Kaepernick’s protest, let alone publicly supported it. On September 23, 2017, in Oakland, A’s rookie catcher Bruce Maxwell kneeled while the anthem played. He was not joined or followed in that action by any baseball player. The dearth of blacks across the sport — on the field, in the stands, and in management and ownership — plays a tremendous role in creating a culture of avoidance. As socially conscious Tampa Bay Rays reliever Chris Archer, who is black, observed: “Just from the feedback that I’ve gotten from my teammates I don’t think it would be the best thing to do for me at this time.” Daniel Russell, “Chris Archer: Baseball Players Face ‘Harsher Criticism’ for Protesting,” SBNation.com, September 25, 2017; Alvin Chang, “This is Why Baseball Is so White,” Vox, October 24, 2017. https://www.vox.com/2016/10/27/13416798/cubs-dodgers-baseball-white-diverse.

2 John Florio and Ousie Shapiro, One Nation Under Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 3.

3 The “crime” for which he was tied to railroad tracks and killed: carrying groceries from the lumber mill store to the front door, not the back door, of a white woman’s house.

4 Billy Staples and Rich Herschalag, Before the Glory (Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications, 2007), 193.

5 Jim “Mudcat” Grant, The Black Aces (Farmingdale, NY: Aventine Press, 2007), 11.

6 Goodwin even arranged a 1949 gig for James and a local choir to sing on Tampa television.

7 Grant, The Black Aces, 210.

8 Steve Jacobson, Carrying Jackie’s Torch (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2007), 57.

9 Grant, The Black Aces, 219.

10 James Grant, telephone interview, January 31, 2018.

11 The black press at the time reported that in 1947 Wilks, then a St. Louis Cardinals pitcher, tried to organize a boycott to prevent having to play against Jackie Robinson and the Brooklyn Dodgers, and regularly threw at the heads of black batters. Sam Lacy, “‘Just Didn’t Jump High Enough,’ Says Thomas,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 20, 1960. https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2205&dat=19600920&id=RWZGAAAAIBAJ&sjid=guUMAAAAIBAJ&pg=992,5140986&hl=en.

12 Steve Jacobson, “[Illegible] Due, but Does Grant?” Newsday, October 19, 1965.

13 Grant, telephone interview; Frank Deford, “Coochee Coos Another Tune,” Sports Illustrated, April 8, 1968, https://www.si.com/vault/1968/04/08/614231/coochee-coos-another-tune; Jay Johnstone and Rick Talley, Over the Edge (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1987), 80; Grant, The Black Aces, 212. Despite reports to the contrary, Grant denies throwing a spitball.

14 Grant, “Life,” Baseball Almanac, March 2002. http://www.baseball-almanac.com/poetry/po_mud.shtml.

15 Grant even hosted a Minneapolis variety television program in 1965, The Jim Grant Show, viewable via the Walter J. Brown Media Archives & Peabody Awards Collection, http://dbs.galib.uga.edu/cgi-bin/parc.cgi?userid=galileo&query=id%3A1965_65008_ent_1-2&_cc=1.

16 Grant, telephone interview.

17 Grant.

18 Deford, “Coochee Coos Another Tune.”

19 Grant met this woman, Gertrude, in 1957, and for a time they were romantically involved. Cleveland management balked at the situation, so they broke things off but stayed in touch discreetly over the years, trying their best to circumvent disfavor from subsequent ownerships. By 1975, when Grant and Gertrude were both divorced from prior partners, they married. They remain together and live in Los Angeles.

20 Grant’s 80 appearances were the sixth highest in baseball history at the time.

21 “East-West All Stars to Play Benefit Game,” The Sporting News, February 21, 1970; Dwight Chapin, “King Game Great — Even for Losers,” Los Angeles Times, March 29, 1970. Grant sang in a white suit before 31,694 fans. The exhibition featured some of baseball’s best players — black and white — and was held to raise funds to benefit King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference and a memorial center planned for Atlanta. Each major-league team sent two representatives, who were divided into East and West All-Star squads. The Joe DiMaggio-managed East emerged with a 5–1 victory over Roy Campanella’s West. Grant pitched one inning, giving up four hits and three runs.

22 Pat Harmon, “Mudcat and His Kittens,” Cincinnati Post, October 7, 1970. Grant performed while surrounded by a mascot mule, clowns, gold bases, a Dixieland band, and mounted patrols. After checking comparable rates for other entertainers who had performed the anthem, Grant calculated and sent Finley a bill for $300. The notoriously cheap Finley refused to pay for quite some time, arguing that he thought Grant would perform this distinctive act for free. Grant held firm until Finley paid. “If he’d just bought me a steak dinner at the time I sang, I’d have called it even. But, the longer I waited, the better my price got,” Grant said.

23 “Hi, There, Waiver Boy!” The Sporting News, October 10, 1970; “Let’s Outlaw Those Late-Season Waiver Deals,” Baseball Sports Stars, 1971. Grant was traded for a player to be named later: young outfielder Angel Mangual. The 1970 trading deadline was June 15. A loophole allowed players such as Grant to be traded if they cleared the $20,000 waiver price from every team, which was practically a certainty given his high salary (about $50,000–$60,000). And even if a waiver claim had been filed, the waiver offer would likely have been revoked. Once clear, clubs could then trade the player(s) in question at “undisclosed” prices, although likely far above the waiver stipend. Waiver-related deals such as this elicited howls from some that teams were attempting to buy a pennant.

24 Grant, telephone interview.

25 Grant.

26 Ellis, who combined pitching prowess with a free spirt attitude and a rarely used edit button when discussing race or anything else, earlier in 1970 had thrown a no-hitter while on LSD.

27 Grant pitched in eight games for the Pirates, going 2–1 with a 2.25 ERA in 12 innings.

28 Grant, telephone interview.

29 Dean A. Sullivan, ed., Late Innings (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 267. The identification of Grant’s 1970 “firsts” — singing the anthem at a regular-season game and at Game Two of the NLCS — is based on personal research and correspondence with Matt Rothenberg, manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, based on available records.

30 Frank Klein, “Making His Point,” Tampa Times, October 5, 1970. In 2015, voluminous coverage and commentary surrounded Serena Williams’s decision to end a 14-year boycott and return to the Indian Wells tennis tournament after she’d experienced racial taunts and criticism there in 2001. How would Grant’s anthem performance have been reported in the modern media? An intriguing question.

31 Milton Richman, “Mudcat Getting Dizzy,” Berkeley Daily Gazette, August 18, 1971; Russell Schneider, “Home Sweet Home is Mudcat’s Theme as Indian Hopeful,” The Sporting News, March 11, 1972. The Pirates went on to win the 1971 World Series. Grant would have received an approximately $18,000 share if he had stayed with the team.

32 Jack Smith, “Reggie: O’s Great,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 6, 1971; Richman, “Mudcat Getting Dizzy”; Grant, telephone interview. Mud for Cats, alas, is not currently available at Sephora or via an old jar on eBay. “Oh, that goes waaaaay back,” Grant guffawed when recently reminded of a cream he had not thought about in years. “You got one of the jars of that stuff, man? I thought that was going to take off, but it never did!”

33 Deford, “Coochee Coos Another Tune.”

34 George W. Bush, “Remarks at a Celebration of African American History Month,” The American Presidency Project, February 12, 2007, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=24522.

35 Mark Sheldon, “Grant a Walking History Lesson,” MLB.com. Accessed at http://www.fergiejenkinsfoundation.org/13black_aces_files/mudcat.htm.

36 Grant, telephone interview; Matt Baker, “Lacoochee’s Mudcat Grant on His 1960s Anthem Moment: ‘Those Were Trying Times,’” Tampa Bay Times, October 13, 2017. http://www.tampabay.com/sports/baseball/rays/lacoochees-mudcat-grant-on-his-1960s-anthem-moment-those-were-trying-times/2340934?curator=SportsREDEF.