Larry Fritsch, Card King: First Full-Time Dealer’s Legacy Continues After 53 Years

This article was written by Tom Alesia

This article was published in The National Pastime: Heart of the Midwest (2023)

In 1989, Larry Fritsch sat in a rural Wisconsin warehouse—big enough to fit a full-sized baseball field and filled with 35 million cards—searching for a player who best exemplified the hobby of cardcollecting.

In 1989, Larry Fritsch sat in a rural Wisconsin warehouse—big enough to fit a full-sized baseball field and filled with 35 million cards—searching for a player who best exemplified the hobby of cardcollecting.

Honus Wagner? Mickey Mantle? Hank Aaron?

“No, no,” said Fritsch, collector extraordinaire and pioneer of the baseball card business. Then his face lit up like he’d just hit a stand-up double. “Vic Raschi,” he proclaimed. Raschi enjoyed an impressive 10-year career in the 1940s and ’50s, playing on six World Series-winning teams with the New York Yankees. But there’s nothing particularly notable about Raschi cards, aside from sentimental value. Fritsch was the sentimental one. “A real stopper,” Fritsch beamed, noting that Raschi had died a few months earlier, in October 1988. “On my baseball card of him, he’s eternally young; he’s Vic Raschi in the ’50s.” Fritsch paused. “I guess the cards are another way of us trying to delay the inevitable.”

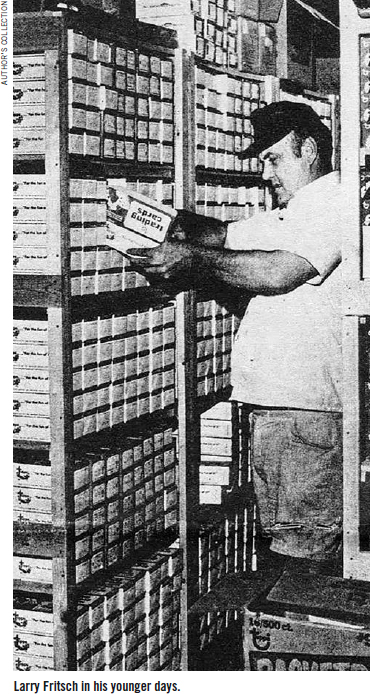

Fritsch was 52 when he made those comments. The Stevens Point, Wisconsin, resident lived another 19 years, always collecting, always selling, always promoting the hobby. He created his company, Larry Fritsch Cards, on May 1, 1970. It marked the first time someone worked full-time buying and selling baseball cards.

During the late 1960s, Larry suffered health problems related to stress. A graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point, where he studied history and political science, he held multiple part-time jobs. He spent 10 years as a train baggage handler. He did tax research for the Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau. He worked at a paper mill. And he collected cards. Always. “A doctor told him that he was doing too much and he needed to cut back,” said Larry’s grandson Jeremy. Then his doctor added some advice: Just do what makes you happy. “That,” Jeremy said, “was a no brainer for [Larry]: Sell baseball cards.”

Larry already had an elaborate collection and enough stock to support his wife and two children, then aged 11 and three. Collectors looked forward to receiving his nearly 200-page catalogues up to six times annually. Still, in 1974, Larry told the Milwaukee Journal that most of his customers were between ages 13 and 16. There was enough interest to maintain the business, but the early years were worrisome. “When we built the first [warehouse] addition in 1975, it cost $20,000. I thought, ‘Holy Christ, how are we going to pay for this?’” Larry said in 1989. “Now I buy a collection for twice that amount and don’t even think about it.”

Fritsch Cards remains a major player in the card hobby business. Late in Fritsch’s life, his son Jeff served as the company’s general manager and unsung visionary. Listed as the company’s warehouse manager at age 16, Jeff ran day-to-day operations for nearly 30 years, before his death in 2017 at age 58. Since then, Fritsch Cards’ majority owner and clean-up hitter (business-wise) is Jeremy Fritsch, Larry’s grandson and Jeff’s son. At 38, Jeremy has 13 years of experience working at Fritsch Cards. In August 2020, he engineered the $1.8 million sale of 12 unopened boxes of 1986-1987 Fleer basketball cards, featuring then-rookie Michael Jordan.

Today, Fritsch Cards operates with seven employees from the same monstrous warehouse on a 26-acre former farm. Larry started expanding it in 1975, after operating the business out of his basement, which also sits on the same property. “I believe there’s a ‘collecting gene.’ I believe that exists,” Jeremy said, sitting at his office, where photos of his grandfather and father hang over his shoulder. “[Larry] definitely passed that gene on to my dad and me.”

Larry’s legacy looms as large as a retractable roof. In 1989, Steve Ellingboe, executive editor of Sports Collectors Digest, called Larry’s collection “by far, the best baseball card collection in the world.” At the time, Fritsch Cards also sold more than 200,000 mail-order cards per week.

Larry bought directly from manufacturers and countless other collectors. He bought just about everything, including thousands of Jell-O boxes with baseball cards on the package. “My grandfather was buying in such quantity that we had 10 people, most of them stay- at-home moms, come in to get a case of cards, take them home, pull them from the wrapping, sort and organize them then bring them back,” said Jeremy. “There’s still stuff in the warehouse we come across that we didn’t know was back there.”

Larry, Jeremy said, was a “borderline hoarder.” His passion, and that of Jeremy’s father Jeff, prevented them from quickly unloading cases. Although many sealed boxes were opened to form complete sets, Larry and Jeff had enough stock to keep many cases untouched. And any unopened case became lucrative- worth far more than the 21,000 cards Fritsch currently has listed on eBay.

Larry was married to Mollie Hendrickson for 27 years, until 1985. After the divorce, Larry still gave her credit for supporting the card sales. “I think of thousands and thousands of hours put in here by my wife and myself,” Larry said in 1989. “This thing didn’t get here by accident.”

For more than three decades, Larry served as the face of the card business. Outlets ranging from Time magazine to talk show host Tom Snyder sought comments from him. Larry was also a familiar face at big card shows. “He was gruff,” Jeremy said. “That’s the exterior he had before he would let you in. It was his way. But once you got close to him or broke down that wall a bit he was kind and appreciative, especially of people who were collecting. He understood what they were going through to get complete sets put together or find that card that they wanted. It’s something he went through himself. He could empathize with that.”

Larry was a wily businessman with an encyclopedic knowledge of vintage baseball cards. He also had a nationwide network of scouts. He paid his “bird dogs” a commission when they discovered certain cards. The deals that Larry made with card companies were significant, but sometimes exaggerated, according to Jeremy. “I’ve heard people say there were full [train] boxcars sent to Stevens Point full of cards. Those are fun myths,” Jeremy said. “He had deals with Topps when they had excess product. But the truth is he bought large quantities because he wanted to sell full sets. He never wanted to run out of stuff. He wanted to say, ‘I have this in my collection,’ or, ‘I have this to sell.’”

Fritsch opened a Cooperstown baseball card museum in 1989. It featured a complete set of T206s from 1909, all in near-mint condition. The museum, which occupied the space of a former Ford dealership, lasted until 1992. Jeff didn’t like to fly, and Larry couldn’t provide enough on-site logistical support while living in Wisconsin. However, the museum made a distinct impression upon a pre-teen Jeremy. He recalled riding a bicycle through the museum when it was closed and stopping often to gaze. “Even then,” Jeremy said, “I thought, ‘This is cool. People come to see all this stuff and I’m around it all the time.’”

Not everything Larry and Jeff touched turned to gold. They bought cases of a football card series with candy canes in each pack. Over time, the candy canes melted and ruined many cards. And Fritsch Cards wasn’t immune to the manufacturers’ glut of products in the early 1990s. “In one of our warehouses,” Jeremy said, “you think you see a wall, but it’s just all the stuff stacked up—and it’s 10 to 12 cases deep packed with early ’90s cards! It’s hard to overstate how much we have.”

Fritsch Cards also created its own series, including cards featuring the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, the Negro Leagues, and players who made the major leagues but didn’t last long enough to have their own baseball card. Jeremy said Fritsch Cards, while maintaining a solid online presence, still publishes and mails more than 10,000 print catalogues twice annually. Because Larry’s wide interests extended to non-sport cards, Fritsch Cards is also planning an entire catalogue devoted to them. The cards range from politicians to entertainers, from the late 1800s to the 1960s.

The COVID-19 lockdowns provided an unexpected boost for Fritsch Cards and the card collecting hobby in general, as many people dove into or rediscovered their love of cards during 2020, but it ended plans for the company’s 50th anniversary celebration. “It went from doing something really big,” Jeremy said, “to having a generic cake from the bakery.”

Fritsch Cards still provides homespun service. With every purchase, whether it’s an unopened box from the 1970s or a $1 card off eBay, they add a simple handwritten note: “Enjoy your card!” This tradition extends back to Larry. “My grandfather also would write a little note about how a card was acquired,” Jeremy said, “or what it meant to him.”

The flashy card variations that are so sought-after today wouldn’t have impressed Larry. “He did say, ‘It was better in my day,’ when he opened something new,” Jeremy said with a laugh. “A color border never meant much to him.”

TOM ALESIA spent his youth at pre-lights Wrigley Field. A longtime entertainment and features newspaper writer/editor, he is author of obscure HOFer Dave Bancroft’s popular 2022 biography Beauty at Short. He won the National Music Journalism Award and wrote the acclaimed book Then Garth Became Elvis in 2021. Find his work at TomWriteTurns.com. A 35-time marathon finisher and a cancer survivor since 1998, he lives in Madison, Wisconsin, with his wife, Susan. They have a son, Mark.

Sources

Alesia, Tom, “Stevens Point collector is king of cards,” Wausau Daily Herald, January 29, 1989.

Jeremy Fritsch, one-on-one interview, February 25, 2023.

“The Sultan of Swap,” Milwaukee Journal, July 7, 1974.

“Larry Fritsch” Obituary, December, 2007. https://www.pisarskifuneralhome.com/guestbook/170319.