Lieutenant Jackie Robinson, Morale Officer, United States Army

This article was written by J.M. Casper

This article was published in Jackie Robinson: Perspectives on 42 (2021)

Jackie Robinson, United States Army. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

The course of history can flip on a dime, the course of one’s life often defined by a series of watershed flash-points. Some we control; others are thrust upon us.

On December 7, 1941, Jackie Robinson was two days into his journey from a sleepy American naval port in Honolulu called Pearl Harbor. As a flume of smoke bellowed in the distance, the Second World War had come to America and found Jackie Robinson. Almost.

Jackie Robinson’s World War II experience tells us a lot about the man Branch Rickey chose to wear the aspirations of an entire race on his broad shoulders. Jack Roosevelt Robinson brought his unique leadership qualities to the service where he displayed an aversion to intolerance and willingness to confront it. Robinson’s experience in the military portends his ability to rouse change. He was at the center of a battle on two fronts, the fight to win a war, and the fight for first-class citizenship. The racism he encountered in the service displayed, prepared, and ushered Jackie Robinson to Brooklyn for a larger calling.

Uncle Sam called upon Robinson for his ability to galvanize morale; Jim Crow then thwarted the notion. Instead, Robinson etched his name into the American storybook as the protagonist in Rickey’s audacious beta test in equal opportunity.

Robinson was a national sensation on the football field at UCLA as part of the Gold Dust Trio at UCLA and wanted to follow in his brother Mack’s footsteps on the track before war canceled the 1940 Olympics. The top scorer on the basketball team played a little baseball too. Exhausted, Robinson hit .097.

Said Robinson in his 1972 autobiography: “I was convinced that no amount of education would help a black man get a job. … I was living in an academic and athletic dream world.”1

The trepidation that led him to leave UCLA was well-founded.2

In August 1941, Robinson starred in the College All-Star game and scored a touchdown against the NFL champion Chicago Bears in front of 98,200 fans at Soldier Field. Fay Young of the Chicago Defender couldn’t help but see connection between the gridiron and the prospect of impending war:

The game ought to make the United States Army and Navy wake up. Every time a Negro is qualified to join a particular branch of service there is a cry that Negro and whites can’t do this or that together. … [T]he Bears played against Robinson and marveled at his ability.3

He found himself in Hawaii because the only offer he could find was to play semipro football in Honolulu on Wednesdays and Saturdays for a $100 stipend and a job, blocks from Pearl Harbor. An ankle injury may have saved his life.4

“I arranged for ship passage and left Honolulu on December 5, 1941,” recalled Robinson, “two days before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. The day of the bombing we were on the ship playing poker, and we saw the members of the crew painting all the ship windows black. The captain summoned everyone on deck. He told us that Pearl Harbor had been bombed and that our country had declared war on Japan.”5

He first bristled when the captain told everyone to put on a life jacket. Then reality set in. His hands trembled in disbelief. A lone target for Japanese bombers, the Lurline juked and jived on the vast waters of the Pacific with the desperation of a running back. Relieved, Jackie Robinson stepped ashore in California.6

“When we arrived home,” remembered Robinson, “I knew realistically that I wouldn’t be there long. Being drafted was an immediate possibility, and like all men in those days I was willing to do my part.”7

On April 3, 1942, Robinson was inducted into the United States Army. His personnel file tells a lot about who Jackie Robinson was as a man. Asked if he had ever been convicted of a crime, Robinson stated “yes,” in his own hand:8

Pasadena, California. Blocking sidewalk 1939 fight was on the corner where a group of colored were watching fight between a white a colored fellow. I was arrested along with some others but was the only on[e] taken in. Case never came before court because of nature of offense.9

Rather than omit the arrest, he chose to disclose the incident. Even a 23-year-old Robinson had a clear sense of moral fortitude. It tells a lot about being Black in America. He was among the lucky ones, recalling that only his notoriety prevented him from becoming a statistic.

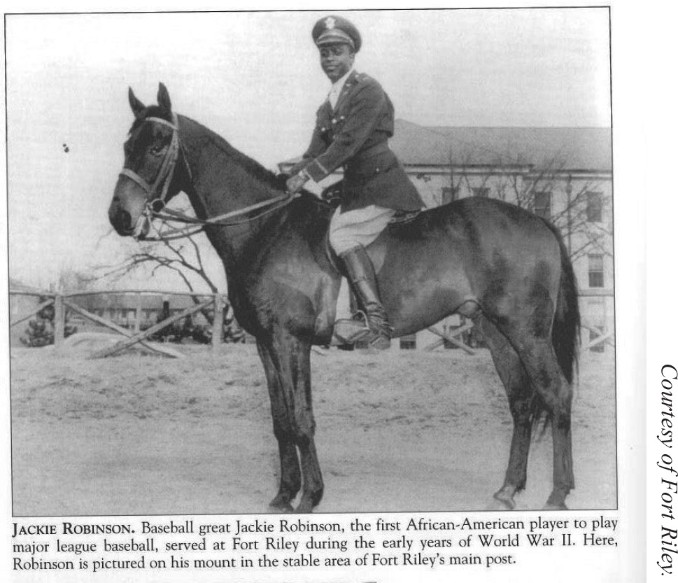

On April 10, Pvt. Robinson found himself on the vast steppes of Fort Riley, Kansas, at the Cavalry Replacement Training Center, though his wife, Rachel, said Jack was never comfortable in the saddle or with a gun.10 Robinson, ever the dogged competitor, grabbed an M1 rifle and qualified as an “expert marksman” on the rifle range, a demonstration of his remarkable athletic talent.

Robinson spent the better part of a year distinguishing himself while training with the segregated cavalry and was promoted to corporal in March. Military brass, however, had no intention of sending Black troops into combat in 1942.

A college man, Robinson was obviously more than qualified to be an officer. Three months after applying to Officer Candidate School, he had heard nothing. Later, he called the slight his first lesson on the fate of a Black man in a Jim Crow army.11

“It seems to me,” wrote Charles Hamilton Houston in a memo to the War Department,” that the Army would wake up to the fact that it cannot keep on treating trained intelligent Negroes as if they were zombies.”12

The racism that permeated every aspect of American society was rampant in the service. Secretary of War Henry L. Stinson opined that Blacks weren’t fit for leadership roles and integration would be detrimental to morale.13 The most egregious problems of race came across the desk of Judge William Hastie, civilian aide for Negro affairs at the War Department, and his deputy, Truman K. Gibson. It was often an academic exercise in futility. Military hierarchy was more concerned with damage control than enacting meaningful change. Black troops were largely consigned to segregated bases and relegated to support roles. In 1943 Hastie resigned in frustration.14

Said Gibson in 2001:

… [W]e constantly just put out the fires. … It was frustrating, at the time because these instances were happening every day, somewhere. … [Y]ou put out the brush fires, but you don’t put out the fire.15

Robinson reflected on his experience in the service thus: “I was in two wars, one against the foreign enemy, the other against prejudice at home.” His sentiment evoked the Pittsburgh Courier’s Double-V campaign started in 1942. 16

“The ‘four freedoms’ cannot be enjoyed under Jim-Crow influences,” wrote Brigadier General Benjamin O. Davis Sr., alluding to President Roosevelt’s famous declaration. The Double-V campaign said a fifth, beside speech, worship, want, and fear should include freedom from racism.17

Luckily for Robinson, Joe Louis – who had the ear of Gibson – also found himself stationed at Fort Riley. The man who passed the baton to Robinson as the torch bearer for Black America also helped pave the way. Robinson and Louis bonded over a mutual love for sport. The Brown Bomber even gave Jack boxing lessons.

It was a fortuitous association.

Now friends, Robinson aired his frustration to Louis about not being commissioned as an officer. Louis placed a call to Gibson, who applied pressure in Washington. In January of 1942, Robinson and a handful of Black candidates were accepted into OCS.18

While quieter than Robinson, Louis was not naïve to the injustices perpetrated on men of color. He just had a different countenance. Louis noted that the Army had problems, but “Hitler was not going to fix them.” He went about things in a more diplomatic fashion than Robinson, who even at the tender age of 24 had an inner fire that was especially fueled by matters of injustice. “Jackie didn’t bite his tongue for nothing,” said Louis of Robinson. “I just don’t have guts, you might call it, to say what he says. … But you need a lot of different types to make the world better.”19

Wrote Robinson in his first autobiography, published with Wendell Smith in 1948:

I sincerely believe it was his worth and understanding, plus his conduct in the ring, that paved the way for the black man in professional sports. My love for Joe Louis goes much beyond what he did in the ring, even his desire to right an injustice. …20

“His arrival,” noted Rachel Robinson, “brought some much-needed power to the Black soldiers and gave Jack an opportunity to form an alliance and work with his longtime hero.”21 Shortly after becoming an officer, Robinson directed his men in a variety show for Black troops as part of the Brown Bomber War Bond Rally that raised over $500,000.22

An apocryphal story by many accounts has Louis saving Robinson from “court-martial, prison and given the lawless nature of race relations in those days, possibly even death,” according to Gibson, after he knocked out the teeth of an officer who called him a n—-r.23

Wendell Smith had a different recollection in the Pittsburgh Courier:

Controversy followed him there. He became embroiled with some MP’s because according to Robinson, they had roughed up a Negro woman passenger on a bus trip while trying to force her to sit in the back. Jack was almost court martialed. … Only the intervention of Joe Louis saved Jackie from a long sentence. Louis appealed to Washington on Jackie’s behalf.24

Apparently a case of champagne showed up in the provost marshal’s office along with some shiny new uniforms from Louis and all was forgiven.

Jackie Robinson, Cavalryman, #14. (COURTESY OF FORT RILEY)

Second Lieutenant Jack Robinson was given a commission as an officer in the United States Army on January 28, 1943, after completing the first integrated 13-week OCS course.25 About one in 10 of the 78 commissioned officers were Black. Robinson wasn’t the only athlete of note in his class. Pete Bostwick, six-time winner of the US Open Polo Championship, was one of the country’s leading steeplechasers. 26

The integrated OCS class was an anomaly at segregated Fort Riley. Fears of racial unrest pervaded the military. Black men could not directly preside over White troops. Troops of color were still relegated to supply lines and logistics. Robinson, now a cavalry officer, was put in charge of a truck battalion.

The morale of servicemen was a tactical priority all too often tested by the indignities of Jim Crow. “The colored man in uniform,” wrote General Davis, “is expected by the War Department to develop a high morale in a community that offers him nothing but humiliation and mistreatment.”27

Singled out for his leadership skills, when the need for a morale officer was pointed out to Army brass, they called on Lt. Robinson.28 He took his solemn duty as morale officer seriously and demanded that his men be treated with respect. Immediately he took to setting an example for his unit, foreshadowing the torch he would bear for all Black America by the end of the decade.

When Robinson went to the segregated Postal Exchange, the social center of any military installation, only a small cadre of seats was cordoned off for colored servicemen. Black troops stood and endured the monotony of waiting in line while White troops cavorted in comfort. Robinson was incensed. He promised his troops he would see to it that Army brass enacted change.

Robinson’s own company was skeptical. They were dubious that their brash morale officer would or could successfully lobby the wholly White chain of command at Fort Riley to get just a tinge of respite and comfort while serving their nation. “Colored” men, as it were, didn’t confront White men with such frivolities and find a sympathetic ear. Many lived in a world where one wrong move could cost them their life. Recalled Robinson:

My statement was met with scorn. I realized that not only did these soldiers feel nothing could be done, but they did not believe any black officer would have the guts to protest. Their pessimism only served to challenge me more.29

Robinson was determined to both incite change and ennoble his men. He picked up the phone and called the provost marshal, whose reaction was reflective of the time. Having never met Robinson, he affably listened to his concern and casually replied: “What if it was your wife sitting next to a n—-r?”

Robinson popped his cork, the shrill nasality of his piercing voice unmistakable to the entire barracks.30 Robinson vividly recalled:

Typewriters in headquarters stopped. The clerks were frozen in disbelief at the way I ripped into the major.

Colonel Longley’s office was in the same headquarters, and it was impossible for him not to hear me. The major couldn’t get a word in edgewise, and finally he hung up. I was sitting there, still fuming, when Warrant Officer Chambers advised me to go to Colonel Longley immediately and tell him what had happened. “I know that the colonel heard every word you said,” Chambers said. “But you ought to tell him how you were provoked into blowing your top.31

Robinson appealed to Longley, who wrote a sizzling letter, as Robinson describes it, to the commanding general.

Robinson’s men got their seats in the PX.32

Jackie Robinson had his first civil-rights victory. Small though it was, Robinson was able to see what moral courage on behalf of his race could potentially accomplish.

My protest about the post exchange seating bore some results. More seats were allocated for blacks, but there were still separate sections for blacks and for whites. At least, I had made my men realize that something could be accomplished by speaking out, and I hoped they would be less resigned to unjust conditions.33

Robinson later opined: “[Longley] proved to me that when people in authority take a stand, good can come out of it.”34

Attorney William Cline’s son recalled that Robinson also took issue with the quality of food that his men received in comparison to their White counterparts, which made him none too popular with the Fort Riley brass.35 Cline Jr. recalls his father opining: “He was a fine officer, he took care of his men.”36

One place where everyone always loved Robinson was on the field. Fort Riley was eager to have one of the best football players in the country on their side in 1943. Then Jim Crow stepped in. The Centaurs opened the season against the University of Missouri, who refused to take the field with an integrated team.37

Put on leave to mollify Robinson without challenging the status quo, he found out the ruse and refused to play on a team that endorsed segregation. He resented the deceit – either he was part of the team or not.38

Recalled Robinson:

The colonel, whose son was on the team, reminded me that he could order me to play. I replied that, of course, he could. However, I pointed out that ordering me to play would not make me do my best. “You wouldn’t want me playing on your team, knowing that my heart wasn’t in it,” I said. They dropped the matter, but I had no illusions. I would never win a popularity contest with the ranking hierarchy of that post.39

Point taken. Robinson would not participate.40

Fay Young of the Defender took note of Robinson’s conspicuous exclusion from the East-West Army football game:

All out for victory they shout, but football fans are at a loss to understand why Jackie Robinson … is not included with the top-notch white gridiron performers who make up the West Army Squad. Robinson played with the 1941 All-Stars in Chicago and came close to being MVP. Today, Jackie is at the Cavalry Replacement Center. … Victory will have no meaning for whites, Negroes or anybody unless it is a victory for all peoples of the allied nations.41

While Robinson could have compromised his ideals and played football, Fort Riley’s baseball team, which resembled a major-league lineup, was also segregated. Pete Reiser, later Robinson’s teammate in Brooklyn, played at Fort Riley and recalled:42

One day we were out at the field practicing “when a Negro lieutenant came out for the team. An officer told him, ‘You have to play with the colored team.” That was a joke. There was no colored team. The black lieutenant didn’t speak. He stood there for a while, watched us work out, and then he turned and walked away. … That was the first time I saw Jackie Robinson. I can still see him slowly walking away.43

In fact, there was a “colored” team, the Golden Mustangs. There is no mention of Robinson taking part.44

During his tenure in the service, Robinson did make his mark in one sport – ping-pong. He won the base tournament. No matter the game, Robinson was a competitive wunderkind. He was an avid tennis player, a sport, along with golf, he continued to enjoy throughout his adult life.

After the court-martial was over, the USO cordially invited Robinson, then stationed at Camp Breckenridge, back to Fort Riley for a ping-pong exhibition against champion Jini Boyd-O’Conner. No reply was given.45

Robinson’s penchant for stepping to the fore was a double-edged sword. He was lauded for his leadership until his principles ran afoul of expectations. Whether the impetus was his brashness or the gravity of impending war, Robinson was transferred and assigned to the 761st Tank Battalion, whose motto was inspired by Louis: “Come Out Fighting.” For three years no one heeded their battle cry, as was the case for all Black combat troops.46

Camp Hood, named for Confederate General John Bell Hood, was in a community overtly hostile to troops of color.47 That enmity often extended to White officers charged with training “colored” units.48 Even Joe Louis was arrested by military police for wearing the wrong uniform in Camp Meade.49

Most White officers viewed being assigned a Black unit as a demotion and treated their men with open contempt. In that respect Colonel Paul Bates was an anomaly. He turned down a promotion to stay with the 761st Tank Battalion, the “Black Panthers.” Rachel Robinson later said her husband was lucky to be commanded by a proponent of fairness in an unjust system.50

Colonel Bates earned the trust of his men by according them respect seldom seen from White officers. Trust often made all the difference when White officers were put in charge of Black troops.51 Bates was a bulwark against the simmering cauldron of bigotry at Camp Claiborne in Louisiana, so bad a race riot broke out shortly after the 761st left for Camp Hood.52 As battalion commander, the colonel let his men know they had to outperform racist presumptions. His is a lesson in leadership in many ways evocative of Branch Rickey.

Robinson, who knew nothing of artillery, was supposed to lead a highly skilled company of tankers. “I decided there was only one way to solve my problem and that was to be very honest about it. I was in charge of men who were training to go overseas.”53

He confessed his ignorance: “Men, I know nothing about tanks.” Robinson asked for their help and learned as he went along. He told his company that as their morale officer he had their back and would see to it that they had all they needed to excel.54 “I never regretted telling them the truth. The first sergeant and the men knocked themselves out to get the job done. They gave that little extra which cannot be forced from men. They worked harder than any outfit on the post, and our unit received the highest rating.”55

Logo of the US Army’s 761st Tank Battalion, known as the Black Panthers. (COURTESY OF FORT RILEY)

Despite his naïveté, Robinson managed to ingratiate himself. Those who didn’t know Robinson from his Gold Dust days at UCLA, were swiftly informed of his athletic prowess when the company played softball. They had to move back 50 feet when he stepped to the plate.56

Robinson’s virtuosity as a leader, an attribute the Army manual emphasizes, was patently obvious to Colonel Bates, who recognized the same inimitable qualities in Robinson as Branch Rickey.

Bates asked Robinson to join his battalion overseas as morale officer and made clear it was for his leadership abilities. He recalled: “[Bates] said that obviously no matter how much or how little I knew technically I was able to get the best out of the men I worked with.”57

When Robinson tried to deflect credit onto his men, Bates told him: “The fact of the matter is you have still have the best outfit of all down here. That’s all that counts.”58

It was not politics or race, but Robinson’s gifted legs, the very thing responsible for his fame that initially stood in the way. For almost his entire time in the service, Robinson was on limited duty, the Army’s version of the disabled list.59

Sadly, fans never saw peak Jackie Robinson on a baseball diamond. Army medical reports are staggering when one considers that Robinson stole home 19 times as a Brooklyn Dodger and wreaked havoc with his legs on the basepaths all the way to Cooperstown.

The ankle he injured in Hawaii, which he first broke in 1937, never had a chance to recover. Every time he ran, it blew up like a balloon. Miraculously, he skipped only a few days of basic training after running the obstacle course. Then he aggravated it while playing softball and became a regular visitor to the infirmary. It might very well be the reason that Bates, also a former college football star, beat Robinson in a race while at Camp Hood.60

Jackie Robinson in cavalry. (COURTESY OF FORT RILEY)

While at Fort Hood he had a rather more perilous encounter with the fog of war. A hand grenade exploded close enough to Robinson to give him a concussion, but it was his chronically arthritic right ankle that kept him from active duty.61

The orthopedic consult from Brooke Hospital paints a harrowing picture – traumatic arthritis in the right ankle, secondary to a nonunion fracture of medial malleolus – he fractured the bone of his inner ankle and they never fused. Loose bodies and bone chips were clearly visible with a simple X-ray. In layman’s terms his ankle was so severely broken it never healed. Later, Sharon Robinson remembered him struggling with his painfully battered legs every day.62

As later, when Branch Rickey came calling, Robinson was eager to embrace the challenge despite the potential perils he knew lay ahead. He traveled to McCloskey Hospital to be cleared for overseas duty. Even a country at war was reluctant to assume the risk.63

Beseeched by Bates, Robinson signed a waiver releasing the Army from any liability should he be injured, just get to the green light from Army brass to join the 761st battalion, who were about to be called into action.64 Given Robinson’s practical nature and devotion to his family, one can deduce the patriotic sacrifice he was prepared to make when he found a dedicated partner.

He wrote, “I might’ve gone but for an incident which indicated that Texas, was in some respects, as hostile to Negro-Americans as Germany or Japan.”65

On the night of July 6, 1944, Colonel Bates received a phone call to rush to the stockade. On his way home from the Officers Club, Jackie Robinson had run afoul of Jim Crow. His arms and legs shackled to a chair, Robinson was livid, his jaw clenched so tightly it was quivering.66

A decade before NAACP activist Rosa Parks’ famous stand, Jackie Robinson was arrested for not moving to the back of the bus. Robinson had not broken any rules, yet there he was about to be court-martialed. Colonel Bates refused to sign the orders. Robinson was summarily transferred.

Robinson said the whole thing might have gone away had he been the “yessah boss” type.67 He showed the same indignance and sense of pride he tried to imbue in his men at Fort Riley when they scoffed at the notion of challenging the status quo.

When Rickey and Robinson engaged in their famous dialectic on bravery, neither man was speaking in hypotheticals. Branch Rickey did his homework. Rickey knew all about his time in the Army and understood Jackie Robinson was no stranger to conflict.

Robinson told the NAACP: “I refused to move because I recalled a letter from Washington which states there is to be no segregation on army posts. The driver insisted I move.”68

“The sight of a Negro sitting beside a woman who might well be white infuriated him,” Robinson later recalled. “I was convinced it was Southern tradition versus Negro.”

“I don’t mind trouble, but I do believe in fair play and justice,” he wrote Gibson. “I will tell people about it unless the trial is fair.”69

Gibson made clear this was a powder keg portending disaster for all parties involved if not handled correctly. California Senators Sheridan Downey and Hiram Johnson were in the loop.70

Without causing a spectacle that might bait the military into making an example of him, Robinson made sure his case wasn’t handled like those of many Black soldiers before. He lobbied behind the scenes. There was no press coverage until after the trial.

Meanwhile, Bates, who deftly told Robinson to go home on leave and forget his problems, had boarded a troopship for Europe with the Black Panthers.

Robinson was provided with an Army lawyer, William Cline, a third-generation country lawyer from Wharton, Texas. Both men initially thought this might not be the best match. White men with deep drawls hardly inspired confidence in men of color.

Cline’s son just happened to be visiting his father at Camp Hood in the summer of 1944. On trial for his life, Robinson was kind enough to meet a young fan. “We had a friendly level of short conversation – as an 11-year-old kid I was thrilled to meet him,” recalled William Jr.71

The starstruck child knew nothing of Robinson’s plight. Robinson had, in fact, told the elder Cline he intended to procure another lawyer. Though the NAACP wanted to be kept in the loop as it were, it didn’t send one.72

Cline recalled: “… [H]e talked about his life. He was a fine man.”

The next day Robinson called and asked Cline to represent him. At trial, Cline poked holes in the racist-tinged lies by many of the witnesses and induced the bus driver to admit calling Jack a “n—–r,” then lying about it. The word was used so much during the war that the Army had to issue a specific directive on how to address people of color.

It took just three hours. On August 3, 1944, Robinson was acquitted.73 By the time it was front-page news in the Baltimore Afro-American74 and the Pittsburgh Courier75, the ordeal was over.76

Robinson called it a small victory, keenly aware that his relative notoriety had again rendered him a lucky man.77

Jackie Robinson never made it into combat. Bigotry had changed his fate. The call of duty that Bates cultivated was no longer there. Robinson sensed that the Army was anxious, in his judgment, to be rid of an “uppity” Black man who had challenged the hierarchy – and won.78

Robinson was put on light duty as a recreation officer at Camp Breckenridge. There he met a friend who played for the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro National League, who mentioned that baseball might be an avenue to pursue.79

When the big push was on into Germany that Spring, I signed with the Kansas City Monarchs for $400 a month. The staggering schedule in the Negro League, the long bus trips, low pay and above all, the humiliating segregation might have depressed me if I hadn’t played hard, driven myself hard to forget the indignities I suffered at Camp Hood.80

The highly decorated Black Panthers spent 183 straight days in combat and were among those to liberate Holocaust survivors, once reconciled to Mauthausen because of their race. 81

In November 1944, after applying to the retirement board, Robinson was given his honorable discharge. Before the ink was dry, he was home in California on the football field, mangled ankle and all, playing at Wrigley Field with the Los Angeles Bulldogs of the Pacific Coast Football League.82

Lieutenant Robinson’s leadership qualities epitomize everything the United States armed forces endeavor officers will impart onto their men. Robinson the officer also mirrored the man who donned number 42 for 10 years. Only his race prevented him from being the quintessential military officer:

I had served in the Armed Forces and had been badly mistreated. When I couldn’t defend my country for the injustice I suffered, I was still proud to have been in uniform. I felt that there were two wars raging at once – one against foreign enemies and one against domestic foes – and the black man was forced to fight both. I felt we must not back down on either front. This land belongs to us as much as it belongs to any immigrant or any descendant of the American colonists, and slavery in this country – in whatever sophisticated form – must end.83

Wrote Wendell Smith in 1972 upon Robinson’s passing: “Jackie Robinson was always himself. He never backed down from a fight, never quit agitating for equality. He demanded respect, too. Those who tangled with him always admitted that he was a man’s man, a person who would not compromise his convictions.”84

Jackie Robinson’s career in the service underscored why America needed Jackie Robinson the baseball player. Called upon by Branch Rickey, Jack Roosevelt Robinson was prepared for what lay ahead. He arrived at their famous meeting already a man who had stood up for first-class citizenship and paid the price. Rickey, like Colonel Bates, chose Robinson for who he was as a man to end segregation in baseball. Again, Robinson answered the call to serve his nation and uplift his race. This time he would not be denied.

JOSHUA M. CASPER is a journalist and author from Brooklyn, New York. A graduate of Hofstra University, he has returned to his passion, documenting the cross-section of history, culture, and sport. Mr. Casper, once a marketing and communication consultant, is published in the United States and abroad, writing about topics ranging from Prince of Wales to the Canyon of Heroes and, of course, Jackie Robinson. He is a passionate fan of the New York Mets and a SABR member, and his work can be found at joshuamcasper.wordpress.com.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Bill Nowlin for the opportunity, patience, and guidance. Special thanks to John Vernon; Pete Kessel; Ivan Harrison Jr.; Carla Crow; Cline family; Jenn Jenson; Mrs. Sharon Robinson; Branch Barrett Rickey; Dr. Robert Smith, CIV Historian Fort Riley; Cassidy Lent, National Baseball Hall of Fame; Jeffrey Flannery, Library of Congress.

Notes

1 Jackie Robinson and Alfred Duckett. I Never Had It Made (New York: Putnam, HarperCollins, 1972), 34.

2 “Robinson Wuz Robbed,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 22, 1941, notes that Robinson, an All-Southern League selection by the coaches of the Pacific Coast Conference in 1940, was left off the 1941 team despite being the basketball conference’s leading scorer for the second season in a row.

3 Fay Young, “The Stuff Is Here!,” Chicago Defender, September 6, 1941: 24.

4 Robinson, I Never Had It Made, 34; Red McQueen, “The Boys Are Going Pure Again,” Honolulu Advertiser, March 11, 1941: 12; Honolulu Star-Bulletin, December 1, 1941, December 3, 1941. Having left on Friday, it appears Robinson sat out the Saturday game before coming home, after he was slated to return and deem questionable during the week. He had also been injured the week before and missed a Wednesday tilt.

5 Robinson, I Never Had It Made, 35.

6 Harvey Frommer, Jackie Robinson (Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons Press 1984). Location 243. Kindle. Also see Roger Kahn, Rickey & Robinson (New York: Rowan and Littlefield, 1982).

7 Robinson, I Never Had It Made, 35.

8 “Robinson Signs With Bulldogs,” Los Angeles Citizen, December 13, 1941.

9 Robinson Military File, Service Record, 39234232.

10 Rachel Robinson and Lee Daniels, Jackie Robinson: An Intimate Portrait (New York: Abrams, 1997), 28

11 Robinson, I Never Had It Made, 36.

12 Letter from Charles Hamilton Houston to Assistant Secretary John McCloy, War Department. Letter in Papers of Hon. Wm. H, Hastie, Hollis Library, September 20, 1944. Addressed to “Mac” from “Charlie Houston,” the NAACP and lawyer mentor to Thurgood Marshall. Houston seems to have found a more sympathetic ear in Assistant Secretary McCloy than Secretary Stimson, whom he bypasses. Marshall, then NAACP counsel, defended one of the mass courts-martial to which this article briefly alludes.

13 Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Ballantine Books), 92, 93. Stimson says this even though troops of color fought in every American war with valor.

14 Research Division Special Service Branch, “Some New Statistics on the Negro Enlisted Man,” Confidential Military Report. Washington, DC: Special Service Branch War Department, 1942. This was a study about Black soldiers that pointed out the demographic shifts from World War I. Northern Black troops had the same level of education as Southern whites. Only 3 percent of World War I Black troops went to high school; 33 percent in World War II. The differences were starker in the North, yet little consideration was given to this, a conclusion realized in 1942.

15 Truman K. Gibson, Oral History, Truman Library. Gibson gives full account of his relationship with Louis, the Robinson affair that is apocryphal, and race relations during World War II.

16 Jackie Robinson, Baseball Has Done It (Brooklyn: IG Publishing, 1964). Anthology that offers comprehensive oral histories of those who followed Robinson and a brief account of his life in the context of the civil-rights movement. It was republished in 2005 by Rachel Robinson, with a foreword by Spike Lee; Double V logo ad, Pittsburgh Courier, February 7, 1942: 1. In this issue a logo of interlocking V’s appeared in the Pittsburgh Courier below the word Democracy with a simple statement: “Double Victory. At Home – Abroad.” Black America’s paper of record began the Double-V campaign, victory over the tyranny of racism at home and victory over tyranny of fascism abroad.

17 General Benjamin O. Davis Memorandum for General Peterson, Washington: War Department Office of the Inspector General, November 9, 1943, archives. gov, “A People atWar.” Davis and Gibson traveled the country to document racism; Edgar T. Rouzeau, “Black America War on Double Front for High Stakes,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 14, 1942. This gives the first explanation of the “Double-V” campaign as part of an editorial.

18 Robinson Military Records, Commission Order, Serial Number 01031586, “Special Order No.19,” January 20, 1943. Robinson had two serial numbers in the Army, one as a private, and the above, 01031586. When Robinson endeavored to retrieve his records in 1958 and confirm his honorable discharge, something that was important to him when he entered the corporate world and began his civil-rights work, this apparently caused some confusion. Another explanation is suspicion of Black civil-rights leaders.

19 Randy Roberts, Joe Louis (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), contradicts Mead and Joe Louis Barrow Jr., Joe Louis: 50 Years an American Hero (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1988). 206; Jules Tygiel, “The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson,” in The Jackie Robinson Reader (Middlesex, UK: Penguin Books, 1997).

20 Jackie Robinson and Wendell Smith, My Own Story (New York: Scribner, 1948).

21 Rachel Robinson and Lee Daniels, Jackie Robinson, An Intimate Portrait (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2014), 28.

22 Emma Brady, “Covering Kansas City,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 2, 1943: 15.

23 Truman Gibson Oral History. Truman Library 2005.

24 Wendell Smith, “The Jackie Robinson I Knew,” Pittsburgh Courier, November 4, 1972: 9. Eulogy for Jackie Robinson from Smith, a close associate and friend during his early career, on his passing. Smith was hired by Rickey as Robinson’s friend and confidant on the road during the lonely and arduous summers of 1946 and 1947, and wrote the already cited autobiography with Robinson in 1948.

25 Michael Lee Lanning, The Court Martial of Jackie Robinson (Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 2020), Kindle Edition, 2020.

26 Robinson Military Records, Roster, 1 of 371, as collated. January 20, 1943, Special Order 19; Horace Laffaye, Polo in the United States (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2011). Before the war, Bostwick Field on Long Island helped make polo a spectator sport for the masses by charging low admission. Not mentioned above are Charles Von Stade, and Louis Stoddard, also polo players. There were two polo charity matches in 1940 before the war. Von Stade also fought in Germany and was killed in 1945 in a Jeep accident. Army polo began at Fort Riley in 1896. To read about the history of Army polo see Laffaye.

27 Brigadier General Benjamin O. Davis, “Memorandum for General Peterson.”

28 Rachel Robinson and Daniels, Jackie Robinson, An Intimate Portrait, 28.

29 Robinson and Duckett, 1. The fact that this opens his memoir shows the import he gave it and its impact on his life.

30 Robinson and Duckett, 38. No one can mistake Jackie Robinson’s high-pitched voice as some call it. But his intonation is nasal, not high-pitched as some mischaracterize. Neither a blind nor deaf individual could mistake Robbie.

31 Robinson and Duckett, 39.

32 Robinson and Duckett, 39.

33 Robinson and Duckett, 41.

34 Robinson and Duckett, 39.

35 Author telephone interview with William Cline Jr., December 2020. Cline’s father was Robinson’s judge advocate at the court-martial hearing as briefly outlined herein. For a comprehensive look at Robinson’s court-martial, read John Vernon, “Jim Crow Meet Lieutenant Robinson,” Prologue, Summer 2008, NARA. [What is NARA? This is the first time it is mentioned.] National Archives Records Administration

36 Cline interview.

37 “Fort Riley Smothered by Missouri,” Minneapolis Star, September 20, 1942: 35. Missouri beat Fort Riley 31-6 without Robinson. The situation foreshadowed Robinson’s first season in the Dodgers organization when the town sheriff of Sanford, Florida, padlocked the stadium lest they countermand the edict of apartheid and endorse voluntary fraternization between the races.

38 Robinson and Duckett, 40; Jules Tygiel, “The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson.”

39 Robinson and Duckett. 2

40 An integrated Fort Knox team played the NFL Pittsburgh Steelers. Wendell Smith, “Smitty’s Sports Shorts: Fort Knox Proves Democracy Still Lives in America,” Pittsburgh Courier, November 21 1942. Smith wrote: “Its roster is a conglomeration of personalities and nationalities, the like of which has never been approached in the history of the Army. It’s a mixed unit, which is something a lot of folks been shouting for since the war started. What is more important is the fact that the soldiers from Kentucky are going around the country playing together and living together.”

41 Fay Young, “Through the Years, Past, Present, Future,” Chicago Defender, September 26, 1942.

42 Pete Reiser’s biography on the SABR BioProject notes other players with whom Reiser played, including Joe Garagiola, Harry “The Hat” Walker, and Rex Barney.

43 Rampersad, 97.

44 That well-chronicled story told by Reiser led many to believe there was no Black baseball at Fort Riley. The Manhattan (Kansas) Morning Chronicle noted the Golden Mustangs of the “colored” Cavalry School Detachment playing baseball and there are references going back to 1917. “Golden Mustangs v. Fort Riley Here,” Manhattan Chronicle, April 26, 1942: 5.

45 Robinson Military papers, Letter to Robinson at Camp Breckenridge from USO.

46 Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Anthony Walton, Brothers in Arms The Epic Story of the 761st Tank Battalion (New York, Crown Publishers, 2005), 19-23 Interviews with Pete Kessel and Ivan Harrison Jr. through the 761st Battalion Alumni Society.

47 Confederate General John Bell Hood led the Texas Brigade during the Civil War.

48 General Davis Memo to General Peterson.

49 “Bomber Louis Freed After MP Arrest,” Chicago Defender, September 4, 1943, National edition.

50 Rachel Robinson and Daniels, 29.

51 General Davis Memorandum. Memo lists nine points of contention regarding race, all of which apply to Robinson. Davis Sr. should not be confused with Benjamin O. Davis Jr. of the Army Air Corps and Air Force.

52 Abdul-Jabbar, 20.

53 Robinson and Duckett, I Never Had It Made, 41.

54 Abdul-Jabbar, 20.

55 Robinson and Duckett, 41.

56 56 Abdul-Jabbar, 51.

57 Robinson and Duckett.

58 Abdul-Jabbar, 21.

59 Robinson Military Medical Records, 1942-1945. Fort Riley, McCloskey Hospital, Breckinridge. The entirety of his time as an officer was on limited duty.

60 David Williams, Hit Hard (New York: Bantam, 1983), 132.

61 Robinson Military Medical Records Progress Notes, Medical Reports. Final Summary.

62 Robinson Military Records, June 29, 1943, Brooke Hospital Notes, McCloskey Hospital, Progress Notes, Reports, Final Summary, Discharge. Limited Duty; interview, Sharon Robinson, October 1, 2020.

63 Robinson Military Medical Records, Transfer, intake progress notes.

64 Robinson Military Papers cleared for limited duty but able to go overseas. Letter, June 21, 1944.

65 Robinson, Baseball Has Done It, 48.

66 David Williams, Hit Hard 127. Williams’s book is a memoir of his time with the 761st Tank Battalion.

67 Robinson, Baseball Has Done It, 48.

68 “Letter to NAACP.” McCloskey Hospital, Temple, Texas: Library of Congress, Robinson File, Legal Trouble, 16 July 1944.

69 Robinson to Gibson, July 16, 1944. NARA.

70 Robinson Military Papers.

71 Author interview with William Cline Jr., December 2020.

72 Carla Crow, “My Visit with Jackie Robinson’s Court-Martial Attorney,” https://artsistuhcrow.blogspot.com/.

73 Robinson Military Records; Charley Cherokee, “National Grapevine,” Chicago Defender, August 5, 1944: 13. The Defender said the War Department was investigating the matter. This is the first mention of the trial, in the Black press, every paper notes the Court-Martial occurring for the first time on 5 August. It already had been adjudicated, but there is no mention. These are, however, all weekly newspapers. No mention is made after.

74 “Grid Star Faces Court-Martial,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 5, 1944.

75 “Lt. Robinson Faces Court-Martial, “Pittsburgh Courier, August 5, 1944: 1.

76 It is often mentioned that a big deal was made in the Black press about the Robinson case. Rampersad notes it. That is not so. While political pressure was present through the NAACP and others, there was no mention until after the trial. The first mention in the press is on August 5. The case was adjudicated on August 5.

77 Robinson says his win was a small victory, then notes his battle on two fronts. Baseball Has Done It, 49.

78 Robinson, Baseball Has Done It, 49.

79 Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 113. There is a minor inaccuracy in Rampersad’s biography. He omits Robinson’s second time the PCFL and seems to confuse the Honolulu Bears with the Hollywood Bears and Los Angeles Bulldogs of the PCFL, a professional league that was integrated. The latter was 1944, while the former is outlined in this story. Robinson signed his PCFL contract while at Camp Breckenridge and played football before playing baseball.

80 Robinson, Baseball Has Done It, 40.

81 It was a subcamp of Mauthausen, Gunskirken Interview, Kessel, Paul confirmed by Hervieux. Other sources have it simply as Mauthausen and earlier sources mistakenly cite Buchenwald; Williams, Hit Hard, 291. Presidential Citation given in 1978 by Jimmy Carter.

82 Robinson’s discharge and potential signing is noted in “Bulldogs Sign Jackie Robinson,” Los Angeles Times, November 8, 1944; “Robinson Makes Local Pro Debut,” Los Angeles Evening Citizen News, November 11, 1944.

83 Robinson, Baseball Has Done It, 117. These comments were made in the context of Paul Robeson and the House Un-American Activities Committee, in front of whom Robinson testified at the urging of Rickey, the only man from whom he took such advice. Robinson was, until the end, staunchly anti-communist, and even in 1972 explains why he detested Robeson. He also quoted Jesse Jackson: “It might not be our country but it’s our flag.”

84 Wendell Smith, “The Jackie I Knew,” 9.