Life in the Bush Leagues of Baseball’s Past

This article was written by Norman Macht

This article was published in When Minor League Baseball Almost Went Bust: 1946-1963

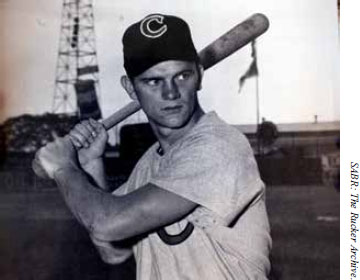

Don Zimmer in Cuba, 1952. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

Cal Ripken Jr. has said, “I had the most fun in baseball in my first year in the minor leagues than at any other time in baseball. Once you get to the major leagues, it’s more of a business.” In my more than 50 years interviewing ballplayers, I often started by asking about those early years. I never met Goldie Holt, but I heard his story from several players.

GOLDIE HOLT

Goldie Holt, who racked up more bus miles as a minor-league player and manager between 1925 and 1958 than an astronaut’s mileage log on a trip to the moon, was managing in Ponca City, Oklahoma, in the Western Association in 1938. The team traveled in an antiquated bus with straw seats, and the players often had to get out and push it. One night it died -again -and they pushed it to the side of the road.

Holt had had enough. “We’ll fix this once and for all,” he said. “Get all the stuff out of the bus.”

The players emptied the bus, then drained gasoline from the fuel tank and poured it all over the bus. Holt lit a match.

Just then a Greyhound bus came along. The driver saw the fire and slammed on his brakes. He leaped out with a fire extinguisher, put out the fire and saved the bus.

As soon as he got back in his Greyhound and drove away, the determined Holt lit it again.

They got a new bus.

JIMMY WILLIAMS

Only a true baseball lifer could enjoy a 40-year career -all but the last seven of them in the minor leagues — and finish with a smile, a million stories, and not a bit of regret over what might have been. Jimmy Williams played in over 2,000 games at every level from Class D to Triple A before finishing his career as a coach for the Baltimore Orioles from 1981-1987, earning a prize that eluded a lot of big-league Hall of Famers: a World Series ring. He shared his stories with us during several visits at his home in Baltimore.

To comprehend what follows, one needs to understand the chain-gang system that once prevailed in baseball. It was created by Branch Rickey when he presided over the St. Louis Cardinals in the mid-1920s and installed in Brooklyn when he moved there in 1943. Jimmy Williams batted .288 in 18 years in the Dodgers’ system, and never swung a bat in the major leagues. His contract was sold from one Dodgers affiliate to another. There was no escape.

But the affable Williams never complained as he traversed the Dodgers’ gulags from Kingston in the North Atlantic League to Montreal (International League), making 15 stops in all. Most of those years he played at Double-A Mobile and Atlanta and Triple-A Montreal, where life was good and the salaries were better than some big-leaguers earned. Remember, this was a time when only the stars -Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, Mickey Mantle, Stan Musial -strode in the thin air of the $100,000 stratosphere. Like most minor-league nomads, Jimmy Williams held other jobs during the winters; for 37 years he never lived and worked a full year in the same town.

Jimmy spent most of his rookie season at Sheboygan in the Wisconsin State League. When the train pulled into the station, he was a third baseman. But when he walked out of the depot, he became an outfielder.

“It was 5:30 in the morning when I got there, too early to call the general manager, so I sat down to wait and got to talking to a guy sweeping out the station. He saw my bag and asked if I was coming to join the Indians and I said yeah.

“He said, ‘What position do you play?’

“I told him third base. ‘Oh,’ he says, ‘we got the best third baseman in the league. ‘

“I said, ‘What about short?’

“He says, ‘Our shortstop looks like he’s going to be rookie of the year. He can really pick it.’

“I said, ‘What about second?’

“‘Oh, that’s Tommy Bartose. He’s been with us for years and, besides, he drives the bus. ‘

“So I’m sitting there thinking all this over and then it’s time to call the GM and he comes and gets me and takes me around town and we go to meet the manager, Joe Hauser, who says to me, ‘What position do you play?’

“I said, ‘What do you need?’

“‘A left fielder,’ he says.

“T play left field,’ I said.

“And that’s how I became an outfielder.”

Like many players, Williams remembers his rookie year at Sheboygan with special fondness. He batted .385 with 105 RBIs in 86 games. And he was named Rookie of the Year, not the shortstop.

“We ran away with the pennant. But what stands out most is the bus rides, talking baseball for hours. At night after a road game, we’d pass through these small towns in Wisconsin, and the manager Hauser, would say, ‘Let’s let them know we’re going through their town.’ So no matter how late it was, we all sang ‘Take Me Out to the Ball Game’ every time we rode through a town.”

Hauser, the home-run king of the minors, who hit 63 for Baltimore in 1930 and 69 in 1933 for Minneapolis, taught Williams a batting lesson he never forgot. “Joe was 48 then, a left-handed batter. He’d grab a new bat and tell us, ‘This is what hitting is all about. I’m going to hit the ball to left field.’ Ping. He’d hit it to left. Didn’t matter where the pitcher threw it. Then he’d say, ‘I’m going to hit it to center,’ and he did. Then he’d point to right and hit one there. ‘You hit for power this way,’ he demonstrated, and hit one over the fence.

“Then he’d show us the bat. There was one mark on it the size of the ball. He had hit every one on the sweet spot of the bat. ‘That’s the secret of hitting,’ he said. That, and hitting the ball out in front of the plate, is all the secret to hitting I ever found.”

After his playing days, Williams managed in the minors for 17 years, beginning at Santa Barbara (Class A, California League) in 1963. He worked at every level except rookie leagues in the Dodgers, Kansas City A’s, Houston, and Baltimore organizations, winning four pennants. He was a strict disciplinarian, making rules and sticking to them. “If I said the bus leaves at 2, we left at 2, and if some guy came running up two minutes later, he was out of luck.”

But he also knew the value of a few cases of beer in the clubhouse after a game to keep the players together talking baseball instead of dressing quickly and scattering. He taught as much from the manager’s traditional seat by the door on the all-night bus rides as he did on the field. But he never hankered to be a big-league manager.

“Sparky Anderson is younger than I am, but he sure doesn’t look it,” he said in explanation.

MEL PARNELL

Mel Parnell was the winningest southpaw in Boston Red Sox history, 123-75 over 11 years beginning in 1947.

“I broke in at Centreville, Maryland, in the Class D Eastern Shore League. It was a friendly town. Everybody knew everybody. We stayed at a boarding house. A local hardware man ran the club. We had a horse to cut the grass. No road trips. We rode the bus home at night after every away game, had a ball holding amateur contests where everybody got up and took a turn doing something, maybe stop and raid a watermelon patch on the way. We were all young. No family responsibilities. Those minor-league days were the most fun I ever had in baseball. Once you get up to the major leagues, it becomes more businesslike.”

ARTHUR RHODES

Left-handed pitcher Arthur Rhodes pitched for nine teams over his 20-year career, the last 15 primarily as a middle reliever against left-handed batters. Rhodes threw his first professional pitch at 3 o’clock in the morning for the Class D Bluefield Orioles (Appalachian League) in 1988.

“I was just out of high school in Waco, Texas, signed a contract and headed for Class D Bluefield in West Virginia. I just had time to find a place to live and the next day we got on a bus to go to Burlington, North Carolina, for two games. I hadn’t even thrown on the side. I was on a pitch limit because I had thrown so much in high school. I was in the dugout until the seventh inning, then went out to the bullpen.”

The game was tied 2-2 after nine innings, and it went on and on.

“I had nothing to eat during the game, just tried to drink a lot of water, eat sunflower seeds, chew bubble gum. It got midnight.

“Then it was 3:00 A.M., and I was the last pitcher in the bullpen. I had to get up and start throwing and then I was wide awake, raring to go. I wanted to throw so bad I didn’t mind going out there at 3:00 A.M. I pitched the 26th. We scored a run in the 27th and I got three outs to end the game. It was my first pro game and first pro win.

The game time was 8 hours and 15 minutes, the longest continuous game in history. Bluefield coach Frank Klebe recalled, “We had to get on the bus to go home, a 3 1/2-hour ride. There was nothing open anywhere to get something to eat. We stopped at an all-night gas station on the way and cleaned out whatever snacks and crackers they had.”

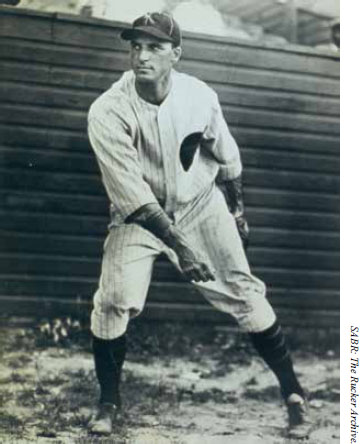

Monte Weaver. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

MONTE WEAVER

Monte Weaver was a right-handed pitcher for Washington 1931-1938 and the Red Sox in 1939. He was the losing pitcher in an 11-inning 2-1 loss to Carl Hubbell and the New York Giants in Game Four of the 1933 World Series.

“I was working on a master’s degree in mathematics at the University of Virginia and teaching when Dr. Booker, a surgeon who owned the Durham club in the Class C Piedmont League, offered me a $500 bonus, $275 a month, and 25 percent of any sale price in 1928.

“Our manager was George “Possum” Whitted, who had been on the 1914 Miracle Braves. He was also the first baseman, bill payer, and groundskeeper. We had a skin infield and every morning he attached a scraper to the back of his Ford roadster and scraped the infield. The ballpark was next to a tobacco warehouse. The smell was so strong it almost made me sick. I tried chewing once, but that was enough.

“One day I was pitching and the batter hit a line drive that split my chin wide open. I went down and Whitted came running over. My chin was bleeding profusely and all he said to me was, ‘Don’t get blood on your uniform.’ The laundry bill was the first thing on his mind. There was a doctor in the stands and he dragged me out to his car and put some metal clips on the cut until I could get to a hospital. I was back pitching three days later, stitches and all.

DON ZIMMER

Infielder Don Zimmer was a baseball lifer; 12 years as a player (1954-1965), four of them with Brooklyn and two with the Los Angeles Dodgers; 12 years as a manager for the San Diego Padres, Boston Red Sox, Texas Rangers, and Chicago Cubs; and 25 years as a coach, the last 11 for the New York Yankees (1996-2006).

“I signed with the Dodgers right after graduation from high school in Cincinnati in June 1949.1 got on a train and went to Cambridge, Maryland, in the Eastern Shore League. Class D. They had told me to go to the hotel in town, an old white building. The first thing I always did, from that day on, whenever I went into a town, I went to the local newspaper office and had the paper sent to my father.

“I called the ballpark. The general manager said, ‘Where are you?’

“T’m at the hotel.’

“‘Be out in front and I’ll pick you up in 20 minutes.’

“It’s about 4 o’clock in the afternoon and it was hot. He came in a pickup truck. I got in and we go to the ballpark. He introduced me to the players. In Class D baseball you were allowed so many veterans and so many limited-service players. The rest were rookies, like me. The manager said to me, ‘You ready to play tonight?’

“‘Yes, sir.’

“They had a veteran third baseman, Hank Parker, and a veteran pitcher, Zeke Zeiss. He was 28 years old, the best pitcher on the team. About my fourth game, I was playing shortstop. Zeiss is pitching. Here came a groundball, took a bad hop and hit me in the neck. You figure it’s called a hit. The next ball I went to field took a bad bounce and hit me on the right shoulder.

“There was a wooden outhouse over beyond first base. The third ball hit to me, I finally caught one. I threw it over the first baseman’s head and hit the outhouse. I figured that was my first real error. Two innings later another ball’s hit over my head between me and the left fielder. I go back figuring the left fielder’s going to run me off the ball. I don’t hear him. I reach out. The ball hit my glove and fell on the ground.

“Later I make another error and we lose. I had botched up the game. As we’re walking off the field, I happen to be walking behind Parker and Zeke Zeiss. The pitcher said to Parker, ‘What are we doing with this guy? He can’t play a lick. ‘

“Parker said, ‘Let me tell you something. You’re 28 years old. This kid played in high school a week ago. Give him a chance. ‘

“I never forgot that. I always respected Hank Parker for kinda sticking up for me.

“A few days later I got a call from my dad. He said, ‘Well, it didn’t take you long to set an Eastern Shore League record. ‘

“I said, ‘What’s that, dad?’

“‘You made six errors in one game.’

“‘Well, I remember making three legitimately.’

“I had a room in a boarding house. We rode in yellow school buses, straight backs, for road trips. It was quite an experience. Eighteen years old, scared to death, going away for the first time, guy picks you up in a truck to take you to the ballpark.”

NORMAN L. MACHT is the author of 36 books including a three-volume biography of Connie Mack. His most recent book, They Played the Game, was published in 2019. He is currently writing for the baseball history website peanutsandcrackerjack.com.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article was edited by Marshall Adesman and fact-checked by Mike Huber.