Los Chorizeros: The New York Yankees of East Los Angeles and the Reclaiming of Mexican American Baseball History

This article was written by Richard A. Santillan - Francisco E. Balderrama

This article was published in The National Pastime: Endless Seasons: Baseball in Southern California (2011)

Los Chorizeros baseball played an essential role in the life of the Mexican American community of East Los Angeles.

Baseball has been a major presence in the lives of Mexican Americans since the early twentieth century. Known as the Golden Age of Mexican American baseball, the years from the 1920s to the 1960s hold particular significance.[fn]The authors want to express their gratitude to a number of individuals who shared their memories of baseball and their families: Bea Armenta Dever, Isidro “Chilo” Herrera, Bob Lagunas, Mario and Frank López, Conrad Munatones, Al Padilla, Richard and Johnny Peña, Armando Pérez,Tom Pérez, Ernie Rodríguez, Saul Toledo, and Art Velarde. Executive Director of the Baseball Reliquary Terry Cannon and research assistant Mark Ocegueda also provided special assistance. We especially want to acknowledge Jean Ardell for her excellent editing and baseball perspective. Finally, to the entire staff at the Pfau Library at California State University at San Bernardino for their tremendous support and assistance on this article.[/fn] On any given Sunday, hundreds and even thousands of Mexican American fans watched games and cheered for their homegrown heroes and teams in such locations as Detroit, Chicago, St. Paul, Topeka, Omaha, Denver, San Antonio, Tucson, Seattle, Albuquerque, Boise, and East Los Angeles.

More than casual pick-up games for youth, these contests involved nearly the entire community. Players and their families loaded up their cars or chartered buses and headed off to their destination, arriving late Friday or early Saturday morning, according to recent work by historians.[fn]The historical literature on Mexican American baseball in Los Angeles and elsewhere is quite limited. However, especially helpful were Samuel O. Regalado, “Baseball in the Barrios: The Scene in East Los Angeles Since World War II,” Baseball History (Summer 1986), 47–59; Richard A. Santillan, “Mexican American Baseball Teams in the Midwest, 1916–1965: The Politics of Cultural Survival and Civil Rights,” in Perspectives in Mexican American Studies, VII (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2000), 132–151; Francisco E. Balderrama and Richard A. Santillan, Mexican American Baseball in Los Angeles (Mount Pleasant: Arcadia Press, 2011).[/fn] They visited family and friends, and in the evening there were large receptions, with food, music, and dancing. The teams socialized at these events, but the next day baseball was serious business. Community pride was at stake. By Sunday night, the visitors were on their way home, having strengthened social and cultural ties with their brethren.

More than casual pick-up games for youth, these contests involved nearly the entire community. Players and their families loaded up their cars or chartered buses and headed off to their destination, arriving late Friday or early Saturday morning, according to recent work by historians.[fn]The historical literature on Mexican American baseball in Los Angeles and elsewhere is quite limited. However, especially helpful were Samuel O. Regalado, “Baseball in the Barrios: The Scene in East Los Angeles Since World War II,” Baseball History (Summer 1986), 47–59; Richard A. Santillan, “Mexican American Baseball Teams in the Midwest, 1916–1965: The Politics of Cultural Survival and Civil Rights,” in Perspectives in Mexican American Studies, VII (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2000), 132–151; Francisco E. Balderrama and Richard A. Santillan, Mexican American Baseball in Los Angeles (Mount Pleasant: Arcadia Press, 2011).[/fn] They visited family and friends, and in the evening there were large receptions, with food, music, and dancing. The teams socialized at these events, but the next day baseball was serious business. Community pride was at stake. By Sunday night, the visitors were on their way home, having strengthened social and cultural ties with their brethren.

Nowhere was baseball more popular than in East Los Angeles, home to the largest concentration of Mexican Americans in the United States and second only to Mexico City in population of Mexican heritage during the early twentieth century. Over the decades, hundreds of industrial, religious, semipro, neighborhood, municipal, park, traveling, amateur, and pick-up teams have played on the fields of East L.A., a tradition that, as this article shows, would have a transformative effect upon the people of that time and place.

Related link: To learn more about the Latino Baseball History Project, click here.

This article focuses on one of East L.A.’s great teams, the Carmelita Provision Company’s Los Chorizeros. Often referred to as the New York Yankees of East Los Angeles by today’s fans, journalists, and historians, Los Chorizeros won numerous city, county, community, andtournament championships between approximately 1948 and 1973, including, for example, the Los Angeles Municipal City championship in 1953, 1955, 1956, 1960, and 1964–65 with a roster of legendary players whose names live as part of community folklore.[fn]Interview with Tom Pérez, 31 August 2010; Interview with Terry Cannon, 16 August 2010.[/fn]

Moreover, long before Fernandomania, “Chorizero-mania” galvanized Mexican Americans politically in the greater Los Angeles area. This article shows the direct connection between Mexican American baseball and the struggle for civil rights.[fn]The article rests upon extensive oral history testimony including Isidro “Chilo” Herrera, Al Padilla, Richard Peña, Ernie Rodríguez, Saul Toledo, Art Velarde of the “Mexican American Baseball in Los Angeles: From the Barrios to the Big Leagues” project in the Special Collections at the John F. Kennedy Library, California State University Los Angeles.[/fn] For much of the twentieth century, the Mexican American experience in the United States was deeply rooted in racial bigotry. This was a time of signs that read “No Mexicans Allowed,” when it was common practice to segregate Mexican Americans in housing, swimming pools, employment, theaters, and restaurants, and deny them access to public parks and participation in organized sports. Even as late as the 1960s, Little League, Colt and Pony Leagues, and Babe Ruth baseball ignored many Mexican American communities, doing little to promote youth baseball. Mexican American communities responded to the racial intolerance in similar fashion as their African American neighbors, bt establishing their own teams, leagues, and tournaments. The history of Mexican American baseball and its socio-political implications in Southern California were largely ignored until the twenty-first century. The beginnings of that recognition are revealed in this accompanying sidebar, the Latino Baseball History Project, based at the John M. Pfau Library at California State University at San Bernardino.

LOS CHORIZEROS

The history of Mexican American baseball dates back to the massive immigration of Mexicans into East Los Angeles during the first two decades of the twentieth century. East L.A. is located east of the Los Angeles River and is linked to downtown Los Angeles by several concrete bridges built by the Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression. The community is both flat and hilly, and is divided into several distinct communities including City Terrace, Boyle Heights, Belvedere, Lincoln Heights, and Maravilla. With the emigration from Mexico, the area of “East Los,” as its residents called it, became truly an American melting pot, with Jewish, Polish, Japanese, Chinese, Armenian, Russian, Turkish, German, and Mexican residents. As other ethnic groups moved on after World War II, Mexican Americans became the predominant group. With this demographic, East L.A., or the Eastside, is now commonly regarded not so much as a particular geographical area but as a symbol of Mexican ethnic identity.[fn]The historiography of the Mexican in Los Angeles has grown rapidly recently but there remains no history of East LA. However, helpful for this period is Douglas Monroy, Rebirth: Mexican Los Angeles From the Great Migration to the Great Depression (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999) for his incorporation of sports including baseball. Rodolfo Acuña, A Community Under Siege: A Chronicle of Chicanos East of the Los Angeles River, 1945–1975 (Los Angeles: Chicano Studies Research Center, UCLA, 1984) for a discussion of key political-socio-economic changes.[/fn]

This ethnic change was reflected in the flourishing of Mexican American businesses such as Mario’s Service Station located on First Street and Hicks. Mario López, the owner of the gas station, had been an avid ballplayer in his native Chihuahua, Mexico, playing well enough on the outstanding Anahuac team to be recruited by the Cleveland Indians when he was only sixteen years old in 1925. But his family refused to allow him to turn professional. After immigrating to the United States in the late 1920s, he played on several teams in the Los Angeles area, including Carta Blanca. In 1942, López decided to sponsor a team under the name of Mario’s Service Station. The team manager was Tommy Pérez, an outstanding right-handed pitcher from the desert area of Victorville-Barstow in California, who had learned to throw a mean knuckeball. Pérez had been a teammate of López on the Carta Blancaclub, and the two men had become close, a friendship so strong that Pérez served as the manager of both of López’s businesses, Mario’s Service Station and later the Carmelita Provision Company. Besides being the team’s ace pitcher, Tommy Pérez managed Mario’s Service Station to at least two or three community championships, with López playing an outstanding shortstop. One major reason that López was able to recruit champion caliber players for his teams was that he liked to give them free gas when they had an outstanding game. After the games, López, Pérez, and the other players would return to the gas station to barbecue and drink beer. After the attack on Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of World War II, with many of the players serving in the military, baseball wassuspended both in the community and at local high schools.[fn]Interviews with Padilla and Tom Pérez.[/fn]

This ethnic change was reflected in the flourishing of Mexican American businesses such as Mario’s Service Station located on First Street and Hicks. Mario López, the owner of the gas station, had been an avid ballplayer in his native Chihuahua, Mexico, playing well enough on the outstanding Anahuac team to be recruited by the Cleveland Indians when he was only sixteen years old in 1925. But his family refused to allow him to turn professional. After immigrating to the United States in the late 1920s, he played on several teams in the Los Angeles area, including Carta Blanca. In 1942, López decided to sponsor a team under the name of Mario’s Service Station. The team manager was Tommy Pérez, an outstanding right-handed pitcher from the desert area of Victorville-Barstow in California, who had learned to throw a mean knuckeball. Pérez had been a teammate of López on the Carta Blancaclub, and the two men had become close, a friendship so strong that Pérez served as the manager of both of López’s businesses, Mario’s Service Station and later the Carmelita Provision Company. Besides being the team’s ace pitcher, Tommy Pérez managed Mario’s Service Station to at least two or three community championships, with López playing an outstanding shortstop. One major reason that López was able to recruit champion caliber players for his teams was that he liked to give them free gas when they had an outstanding game. After the games, López, Pérez, and the other players would return to the gas station to barbecue and drink beer. After the attack on Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of World War II, with many of the players serving in the military, baseball wassuspended both in the community and at local high schools.[fn]Interviews with Padilla and Tom Pérez.[/fn]

By 1948 López had closed his gas station and was looking for new business opportunities. He remembered vividly that upon his arrival in East L.A. in the 1920s, few local markets carried popular Mexican food products, such as pigs’ feet, chicharrones (pork rind), or chorizo (pork sausage). López, who had worked at a meatpacking plant from 1934 until 1942, began to produce chorizo and other popular Mexican pork items at the Carmelita Provision Company, named for Carmelita Avenue, where his factory was located. With the postwar demand increasing for familiar, good-quality food products by the rapidly growing Mexican community, the business prospered.[fn]Los Angeles Times, 30 November 2008.[/fn]

Francisco “Pancho” Sornoso was an original co-owner of the Chorizeros for about six years along with Mario López. While he was not as active as López regarding baseball operations, Sornoso attended most of the games and traveled with the team to Mexico. His main responsibilities included customer service, purchasing pork, and selling Caremelita products. According to hisson Frank, López’s focus on family, baseball, and business continued after he purchased the pork factory, and he soon formed a new team. Once again, López asked his good friend Tommy Pérez to be his manager. Just as they had done with the gas station team, both Pérez and López played on the team. López purchased the uniforms at the Bell Clothing Company. According to former players, the uniform had the team initials CPC stitched in cursive across the chest, smart-looking ball caps, and warm-up jackets. After winning its first community championship in 1948, one of the players, Saul Toledo, nicknamed the team Los Chorizeros (the Sausage Makers), and the moniker stuck.[fn]Interviews with Frank López, 7 September 2010, Saul Toledo, 12 March 2010; Tom Pérez interview.[/fn] The team logo was a pig with a baseball cap holding a glove and bat.

López used his new wealth to help those in the community who were less fortunate, giving away packages of chorizoto fans in the bleachers. After games he liked to invite his teammates to a local East L.A. restaurant-bar named the Joker’s Den located near the famous Cinco Puntos (Five Points) for the five streets that intersect near Brooklyn and Lorena, or the Silver Dollar on Whittier Boulevard, or other watering holes, where he picked up the tab for tacos and beer. One of the players’ wives, Louise Toledo, recalled that she and the other wives waited with their children in their cars while the men drank and ate at the pleasure of Mario López.[fn]Toledo interviews.[/fn]

Los Chorizeros were an amateur team, thus the players were not paid. They played for their great love and passion for baseball, according to Bea Armenta Dever, the daughter of Ray Armenta, one of the great local ballplayers. She noted that her father was fearless when challenging umpires’ decisions and sometimes would go nose to nose with the men in blue. She added that, like most ballplayers of his era, her father sustained periodic injuries on the field, but they never stopped him from playing his heart out. Like many players, he was constantly whistling, chattering, and encouraging his team. When he made a mistake, he never put his head down or quit, regardless of the score.[fn]Correspondence of Bea Armenta Dever to the authors, 13 July 2010, 25 July 2010 as well as correspondence between Armenta Dever to Terry Cannon, 9 February 2008.[/fn]

Former players grow nostalgic over those years when teams gave youngsters ten cents to shag fly balls, damaged bats and worn-out balls were almost completely wrapped with tape, players left their gloves on the field for the opposing team to use, rosin bags were on either side of the mound instead of the back of the mound, balls landed in nearby park swimming pools, young boys worked the manual scoreboard in center field, players wore wool uniforms, rookies learned to drink beer, spectators sat on the grass or makeshift stands to watch games and enjoy a picnic, players had to get the fields into shape, only two balls were used for the entire game, and the winning team took home the game balls.[fn]Interviews with Al Padilla, Richard Peña, Ernie Rodríguez Saul Toledo, and Art Velarde of the “Mexican American Baseball in Los Angeles: From the Barrios to the Big Leagues” project.[/fn]

Los Chorizeros played at various local fields—Fresno, Belvedere, and Evergreen parks under the administration of the Los Angeles Department of Parks and Recreation, which established the rules and regulations of the games, including the responsibilities of the managers and umpires, and team equipment. Game day was usually Sunday. Ninety-year-old Saul Toledo, who played with the team from the early 1940s into the 1960s, is one of the oldest living Chorizero players. During his tenure, Toledo not only played baseball but also promoted the team through newspaper articles he wrote in the local press including “Midget” Martinez Sports Page and La Publicidad, hosted a local radio show on baseball, and served as a public address announcer after his retirement from playing baseball. Toledo’s memories are sharp, and he speaks fondly of both the hard-fought games and the many friendships forged with players, their families, and loyal fans. He noted that the majority of teams they played against were Mexican American, but there were also teams made up of largely of African Americans, Asian Americans, and other ethnic groups. The teams that they played against, many times for the city championships, mirrored the ethnic diversity of the greater Los Angeles area—Jalisco Beer, Eagle Rock All Stars, Coast Meats, L.A. Braves, L.A. Coasters, Watts Giants, L.B. Grays, Hawthorne Merchants, North American Knights, Evergreen Cubs, Sons of Italy, Central Monarchs, L.A. Royals, Dow Painters, G.M.C. Trucks, Carta Blanca, and Hermanidad Sastres.[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

Los Chorizeros played at various local fields—Fresno, Belvedere, and Evergreen parks under the administration of the Los Angeles Department of Parks and Recreation, which established the rules and regulations of the games, including the responsibilities of the managers and umpires, and team equipment. Game day was usually Sunday. Ninety-year-old Saul Toledo, who played with the team from the early 1940s into the 1960s, is one of the oldest living Chorizero players. During his tenure, Toledo not only played baseball but also promoted the team through newspaper articles he wrote in the local press including “Midget” Martinez Sports Page and La Publicidad, hosted a local radio show on baseball, and served as a public address announcer after his retirement from playing baseball. Toledo’s memories are sharp, and he speaks fondly of both the hard-fought games and the many friendships forged with players, their families, and loyal fans. He noted that the majority of teams they played against were Mexican American, but there were also teams made up of largely of African Americans, Asian Americans, and other ethnic groups. The teams that they played against, many times for the city championships, mirrored the ethnic diversity of the greater Los Angeles area—Jalisco Beer, Eagle Rock All Stars, Coast Meats, L.A. Braves, L.A. Coasters, Watts Giants, L.B. Grays, Hawthorne Merchants, North American Knights, Evergreen Cubs, Sons of Italy, Central Monarchs, L.A. Royals, Dow Painters, G.M.C. Trucks, Carta Blanca, and Hermanidad Sastres.[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

After a few years, Tommy Pérez resigned as manager and another key individual in the history of Los Chorizeros was selected to manage the team, Manuel Pérez (no relation to Tommy Pérez), affectionately know as “Shorty.” If Los Chorizeros were the New York Yankees of East L.A., Shorty was Joe McCarthy, Casey Stengel, and Joe Torre all wrapped into one. He, along with Mario López, were the glue that kept the team together for nearly 35 years—an unprecedented number of years for any community team in the greater Los Angeles area and possibly in the United States. During his reign, Shorty’s teams won numerous championships at the city and community levels. One of the great games of his managerial career took place at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles in 1961 when Los Chorizeros beat Venice, 3–2, in the Los Angeles City Finals, prevailing over pitcher Joe Moeller, who was about to sign a lucrative contract with the Los Angeles Dodgers and enjoyed a good professional career with the team.

As described by Saul Toledo, Shorty’s typical Sunday began by attending Mass with his family, after which he returned home, loaded his car with bats, balls, gloves, chest protectors, and bases, and headed off to the baseball diamond. Shorty and his son would drag and water down the infield, chalk the foul lines, and make sure that all was ready for both teams and the thousands of fans. Once, when the team was short of catchers, Shorty went behind the plate and caught the entire game—at the age of 65.[fn]Toledo interview; KCET “Life and Times” Television Program, 19 April 2006; KTLA News, 30 April 2006; Regalado, “Baseball in the Barrios,” 47.[/fn]

Game day was an exciting time for the entire community. The players would arrive early at the park to help prepare the playing field. Some of the wives and girlfriends would set up food stands, where they sold beef tacos, tamales, chorizo and egg burritos, beans and rice, and a variety of soft drinks and beer including Dos Equis, Lucky Lager, Brew 102, Pabst Blue Ribbon, and Eastside Beer. Music was often provided by an assortment of musicians including mariachis, strolling trios, and individual musicos. In the stands, the fans cheered for their favorite teams and players, rooting and good-naturedly ribbing in both English and Span- ish. There was loud laughter and gossip among friends and families. Dozens of children played in nearby sandboxes and on swings under the watchful eyes of their older brothers and sisters.

In a more serious vein, Los Chorizeros played during a turbulent time and place for Mexican Americans, for the 1930s to the 1960s saw a series of racially charged events and conflicts in Los Angeles. During the Great Depression, for instance, Southern California businesses and county charities targeted thousands of local residents for expulsion to Mexico. By conservative estimates one-third of the Mexican community was forced to flee Southern California to Mexico. Baseball player Al Padilla vividly recalled his mother’s fear that the family would be sent to Mexico.[fn]Interview with Al Padilla, 3 August 2010. [/fn]In the 1940s, racial intolerance directed specifically at young Mexican Americans again erupted. In 1942 The Sleepy Lagoon Case involved two dozen Mexican youths who were found guilty in a highly publicized murder trial. That led the following year to physical confrontations between U.S. servicemen and young Mexican Americans wearing the popular zoot suit. In the “Bloody Christmas Incident” of 1951, seven Mexican American prisoners were beaten by police officers at the Lincoln Heights jail. “Operation Wetback” of 1954 was yet another campaign to deport Mexicans. Then there was the eviction of the Mexican American community of Chávez Ravine in the 1950s to provide land for Dodger Stadium. The 1960s marked the birth of the Los Angeles Chicano movement protesting the war in Vietnam, police brutality, deportations, and inferior public education.[fn]Among the best and most recent studies of politics with significant information on the Los Angeles Mexican Eastside is Kenneth C. Burt, The Search for a Civic Voice: California Latino Politics (Claremont: Regina Press, 2007). [/fn]

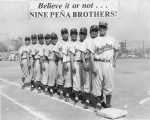

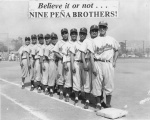

Chorizero baseball games provided both players and their supporters with a safe and convenient forum to discuss their labor struggles, political issues, and stratagies to confront racial discrimination. Ethnic and political solidarity was manifested at games. Mexican American labor and political leaders attended games along with community leaders from local and national groups such as the Community Service Organization and the American G.I. Forum. “Smart politicians attended the games, because that was where the Mexican people were—at the church and ballpark,” observed Chorizero ball player Johnny Peña.[fn]Interview with Johnny Peña, 8 September 2010. [/fn] For example, Los Angeles City Council member and later Congressman Edward R. Roybal and famous singer-guitarist and activist Eduardo “Lalo” Guerrero frequently attended games. Among the children was future film star Edward James Olmos.

Chorizero baseball games provided both players and their supporters with a safe and convenient forum to discuss their labor struggles, political issues, and stratagies to confront racial discrimination. Ethnic and political solidarity was manifested at games. Mexican American labor and political leaders attended games along with community leaders from local and national groups such as the Community Service Organization and the American G.I. Forum. “Smart politicians attended the games, because that was where the Mexican people were—at the church and ballpark,” observed Chorizero ball player Johnny Peña.[fn]Interview with Johnny Peña, 8 September 2010. [/fn] For example, Los Angeles City Council member and later Congressman Edward R. Roybal and famous singer-guitarist and activist Eduardo “Lalo” Guerrero frequently attended games. Among the children was future film star Edward James Olmos.

The era in which Mexican American baseball flourished in Los Angeles, epitomized by the emergence of Los Chorizeros as a powerhouse, must be viewed within the context of the racial strife of the times and the community’s ultimate response. Each intrinsically influenced the other. Mexican American players played ball on Sunday but during the rest of the week many became active in political and labor organizations to promote the preservation of the Mexican culture and language against cultural assimilation. A number of Chorizeros recalled that they and their families became involved in campaigns to secure a voice for their community, particularly in Edward Roybal’s successful campaigns for Los Angeles City Council in 1949 and United States Congress in 1962.[fn]Interviews with Padilla, Peña, Toledo. [/fn]

So baseball played an essential role in the life of the Mexican American community of East Los Angeles. Involvement in the game taught young people the rules of fair play, helped develop their physical and organizational skills, helped channel their competitiveness in a positive way, promoted civil and labor rights, reaffirmed cultural values and traditions, and forged a national identity for people of Mexican heritage by bringing them together across miles and circumstances to the baseball diamond. For some Mexican Americans, these games mirrored larger racial and class struggles that transcended the playing field, as community members often faced reprisals and harassment for being brown. On the field, what essentially mattered was that you played well, not the color of your skin. But what went on among the spectators during and after the games was equally important, for such contests often had social, political, and cultural objectives. According to historian José M. Alamillo, Mexican Americans used baseball to demonstrate their equality through athletic competition and to broadcast community solidarity and strength.[fn]See José Alamillo, “Peloteros in Paradise: Mexican American Baseball and Oppositional Politics in Southern California, 1930–1950,” Western Historical Quarterly, XXXIV: 2, 191-212 as well as “Mexican American Baseball: Masculinity, Racial Struggle and Labor Politics in Southern California, 1930–1960,” in John Bloom and Michael Willard, (eds.) Sports Matters: Race, Recreation, and Culture. (New York: New York University Press, 2002).[/fn] Like family and religion, baseball was an institutional thread that united the community. These political conversations strengthened the communal sense of political empowerment and ethnic solidarity. The baseball field became another instrument for political organizing in the cause of civil and human rights. Mexican Americans in East Los Angeles had heroes to look to, teams to rally around, and shared experiences with which to build a stronger sense of cultural unity and common purpose for themselves and their children. One of the teams they looked up to was Los Chorizeros.

Many of the old ballplayers are now gone. Among them is Mario López who passed away at the young age of 57 in 1966. Unfortunately, López did not live to see his Mexican pork products become mainstream items in American chain stores and markets of the late twentieth century. Both Tommy Pérez and Shorty Pérez, the first and second managers of Los Chorizeros, also are gone. Tommy died in 1987 and Shorty in 1981. Shorty was buried in his uniform with a baseball autographed by his players and others. Shorty also had the distinction of being the first person inducted into the short-lived Carmelita Chorizeros Hall of Fame.[fn]Eastside Journal. Belvedere Citizen, 2 December 1981.[/fn]

Many of the Chorizero players went on to become educators, probation officers, political and business leaders, coaches, and professors.[fn]Many Barrio baseball players including the Chorizeros dedicated their lives to careers in education as teachers and coaches such as Conrad Munatones, Al Padilla, Armando Pérez, and Ernie Rodríguez. See interviews of Al Padilla, Armando Pérez, Ernie Rodríguez, of the “Mexican American Baseball in Los Angeles: From the Barrios to the Big Leagues” project.[/fn] And many of them continue to speak at schools, raise scholarships, and promote youth sports. Los Chorizeros’ legacy continues whenever a Mexican American youth team takes the field. They were the foundation long ago that helped establish East Los Angeles into a true Field of Dreams for thousands of youths. To this day, the team logo sits prominently on the top of the Carmelita Provision Company factory building, where thousands of commuters on the Long Beach Freeway can still see the little pig with his bat and glove.[fn]After the death of Shorty Pérez, Francisco “Frank” Corral managed the team until his untimely death in 2005. During his tenure Los Chorizeros won several more community, league, and tournament championships but not at the city level nor with the skillful players that dominated baseball from 1948 to the 1970s. Los Chorizeros still play today, appearing in August of 2010 as an all-star team in the city of El Monte. The club, however, can best be described as a pick-up team. Mario López’s son, Frank, is often asked to throw out the first ceremonial pitch in respect to his father’s legacy. Interview with Frank and Mario López, 8 and 9 September 2010.[/fn]

Dedication

The authors wish to dedicate this article to the memory of Saul Toledo, who died on September 28, 2010, as we were completing this article.

FRANCISCO E. BALDERRAMA is Professor of Chicano Studies and History at California State University Los Angeles and also serves on the planning committee and the advisory board of the Latino Baseball Project: the Mexican American Experience. Balderrama has taught “Mexican American Baseball: An Oral History Approach” at Cal State LA with particular attention to directing students in conducting interviews of players and fans. The golden age of amateur and semi-professional baseball for Mexicans in East Los Angeles, which instilled ethnic pride and identity during the early 20th century, is a major research area of Balderrama. This interest led Balderrama to co-author with Richard Santillan the book “Mexican American Baseball in Los Angeles” (Arcadia Press, 2011).

RICHARD SANTILLAN is a Professor Emeritus of Ethnic and Women’s Studies at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, where he has taught for 31 years. He also serves on the planning committee and advisory board of the Latino Baseball Project: The Mexican American Experience. Dr. Santillan has written extensively on Mexican American baseball history in the Midwest United States. He is a longtime Los Angeles Dodgers fan with special interest on Mexican American players who have played for the Dodgers since the team’s arrival in 1958. Dr. Santillan is co-author with Dr. Francisco E. Balderrama of “Mexican American Baseball in Los Angeles” (Arcadia Press, 2011).