Lou Gehrig and Cal Ripken Jr.: Two Quiet Heroes

This article was written by Norman Macht

This article was published in The National Pastime: A Bird’s-Eye View of Baltimore (2020)

As I write this, I am aware that I might be the only person alive who saw Lou Gehrig play and was present at Camden Yards the night Cal Ripken Jr. broke Gehrig’s 2,130 consecutive game record. I was an eight-year-old fan when I saw Gehrig at the original Yankee Stadium in 1938. I was a stringer for Sports Network in the press box at Oriole Park on September 6, 1995.

That night I knew I wasn’t the only person in the ballpark who had seen both men in action. Joe DiMaggio was there, too, overshadowing lesser celebrities like President Bill Clinton and Vice-President Al Gore.

Both Gehrig and Ripken had the same attitude toward their job: If you could walk you showed up for work. You took care of yourself, ate healthy foods, stayed in shape, and practiced assiduously to improve. Gehrig made himself into a capable first baseman. Ripken always seemed to be experimenting with his batting stance. Ripken once said, “The most fun I ever had in baseball was in the minor leagues. After that, it was a business.”

Both were quiet men — not exactly aloof, but neither courting the spotlight. Both earned the respect and admiration of their teammates. In the Orioles’ expansive clubhouse, Ripken had three lockers — those on either side of him vacant — in the farthest corner. In the pregame clubhouse you could chat freely with Elrod and the other coaches, or with Brady, Roberto, Rick, and Will, but you didn’t approach Cal without a purpose or appointment. At least I didn’t. I was a freelancer, not a beat writer. If I had some specific questions to ask him, I would request a time through the Orioles’ PR man, John Maroon, then stand in the clubhouse, noticed but ignored, until Ripken beckoned.

Kids idolized both men. Kids also revered Babe Ruth, but youngsters saw him more as as a big kid himself, built for fun, more than as a hero. For my thirteenth birthday, I received an aptly-named book: Lou Gehrig: A Quiet Hero. But in the 1930s, how did we know anything about our heroes? There was no TV; no New York teams’ games were broadcast on the radio. We knew them only through reading the sports pages of the many New York newspapers, The Sporting News, and Baseball Magazine. I was 11 when Gehrig died, just two years after his last game. Millions wept, including me. The loss was beyond my understanding: old people died, not young athletes.

Cal Ripken Jr. is also a quiet hero. In his playing days, if a writer mentioned that he or she had talked to him, wide-eyed Baltimore youngsters would gasp, “You know Cal ‘Wipken’?” Before games, Junior would be the last man standing at the box-seat railing, signing autographs for the kids and adults waiting in line.

Gehrig hadn’t missed a game in nine years, but in the 1930s little attention was paid to obscure stats like that. The record of 1,307 consecutive games played, held by Yankees shortstop Everett Scott, had quietly ended on May 6, 1925, merely 3.5 weeks before Gehrig’s streak began. In 1933, when a New York sportswriter called to his attention that Lou was closing in on the record, Gehrig became very conscious of it. Gehrig broke Scott’s record on August 17, 1933, and with each game he played until May 9, 1939, he extended his own record.

Sometimes he made token appearances to keep the streak going. On July 13, 1934, Gehrig awoke in Detroit with rheumatism in his back. He could hardly move. He singled his first time up, almost fell going to first, and left the game. The next day he felt worse. He asked manager Joe McCarthy to let him lead off. McCarthy listed him at shortstop, batting first. Gehrig singled, then left for pinch runner Red Rolfe, who played short.

He played through more ailments and broken fingers than Ripken, who had both good luck and the advantages of better, more professional trainers and facilities. In Gehrig’s day, a rolling pin for kneading out muscle knots was standard trainer’s equipment. He played through broken fingers, rheumatism, heavy colds, and his last full season with the early effects of the debilitating disease that would kill him three years later. In a midseason exhibition game one year, he was hit in the head by a fastball and knocked unconscious. No fracture, just a big bump. He insisted on playing the next day, lest he become gun shy at the plate.

Unlike Gehrig, Ripken ground it out, every inning every game until 1987, when O’s manager Cal Sr., sat him down in the ninth inning of a game near the end of the season, after 8,264 consecutive innings. He was lucky, avoiding serious injury while playing the most demanding infield position except catching. The streak was important to Ripken, but not more important than playing to win. He played through ankle sprains and minor aches and pains, the worst when he twisted an ankle on June 6, 1993, in a 20-minute brawl sparked by O’s pitcher Mike Mussina hitting Seattle’s Bill Haselman with a pitch; seven players and Mariners’ manager Lou Piniella were ejected.

Ripken’s run-up to the record was ballyhooed to the hilt. For the preceding week, a banner hung on the side of the warehouse beyond right field, displaying Ripken’s consecutive game count each day. In the fifth inning — when each game would become official — the new number was unfurled.

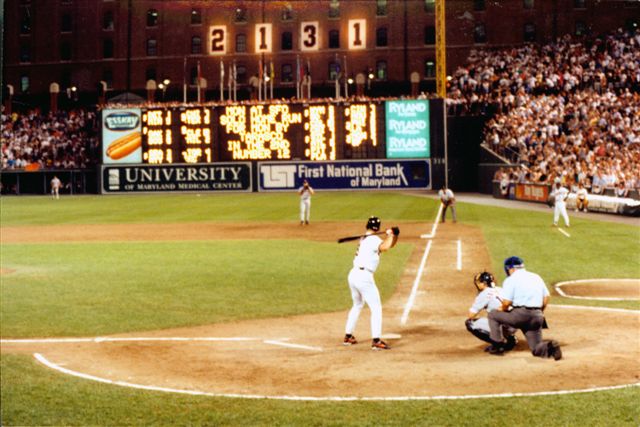

On the night of September 6, 1995, in front of an announced crowd of 46,272 fans, some of whom had paid scalpers $200 or more for upper deck seats (remember, this was 25 years ago) plus guests like Clinton, Gore, and DiMaggio — and a crowded press box were present for the historic game against the California Angels. In the bottom of the fourth Bobby Bonilla homered, Ripken homered, and the Orioles led, 3–1. In the top of the fifth, Orioles ace Mike Mussina had a quick three-up, three-down inning. It was as if nobody could wait for the game to become official.

Then, the 2131 banner unfurled and the noise and fireworks began, the raucous crowd trying to overpower the fireworks. Calls came for Ripken to step out of the first base dugout and take a bow … no Ripken. The crowd’s chant grew louder. Finally, teammates pushed him out and he began a 22-minute lap along the seats around the ballpark. Angels players stood in front of their dugout and applauded as he passed.

After the game, the clubhouse-level concourse beneath the stands was bustling. Ted Koppel, host of the popular Nightline TV show, surrounded by cameramen and flunkies, pushed his way into the clubhouse past an unnoticed Joe DiMaggio, who was patiently signing autographs. Reporters scurried to an auxiliary clubhouse for a Ripken press conference. Long after midnight people were still milling around; there was no effort to shoo them out.

Both men ended their consecutive-game records without ceremony or fanfare, as low-key as the men who had achieved them. As the Yankees breezed to another world championship in 1938, Gehrig began to feel sluggish. He still hit 29 home runs and drove in 114, but his batting average dipped below .300 for the first time since his rookie year. He had four hits — all singles — in the four-game Series. That winter he felt tired, often stumbling while walking. But he thought he’d bounce back in the hot weather of spring training. He didn’t. He couldn’t pick up ground balls, couldn’t hit with any power, almost fell when he ran. To get up the steps between the dugout and clubhouse, he had to grip the railing and pull himself up. His teammates were bewildered: what was wrong with Lou? But no one suggested he sit down or take a rest. They had too much respect for him.

After opening at home against Boston, the Yankees went to Washington for three games, in which he had one hit. A 14-year-old fan from the Eastern Shore, Gil Dunn, was at one of those games. Fifty years later he recalled,

After the game I was outside the stadium and Gehrig came out and brushed right by the boys asking for autographs and got into a taxi. He was alone, and he looked so dejected. He was walking bent over like an old man, graying at the temples, and I had never seen a man who looked so downhearted. I stood there and I felt sorry for him. Here he was one of the great heroes of baseball and I was feeling sorry for him.

Gehrig had four hits — all singles — in the first eight games when they headed to Detroit. But it wasn’t his weak hitting that prompted his decision. The last straw for him came when he had made a routine play in the field and his teammates overdid it with their effusive “great play!” pats on the back. On the morning of May 2, he went to manager Joe McCarthy’s room and said, “I need a rest. I’m not doing the team any good.” He knew it was the end of the streak, but he didn’t know he’d never play again. The Iron Horse had run his last 90 feet.

Although still able to play, Cal Ripken decided to relieve the constant speculation over when and how his streak would end by ending it himself near the end of the 1998 season. By then he had so far surpassed Gehrig’s record, the count was rendered unimportant. Nobody in the future was likely to come close, and if they did, more power to them. He was 38 and knew he was no longer an everyday player. In 1997 he had switched to the less demanding third base position. The Orioles were a .500 team. Ripken wanted no ballyhoo, no ceremony, no fuss.

The last home game of the season was Sunday night, September 20, 1998, against the Yankees. Before the game he told manager Ray Miller he wanted out of the lineup. And that was it: game 2,632. None of the reported 48,013 fans who filled Camden Yards knew what they were about to witness until the public address announcer, reading the lineup, said, “Batting sixth, the third baseman, Ryan Minor.” Minor was a 6-foot-7 rookie who had made his debut as a pinch hitter on September 13. (Great trivia question: who replaced Cal Ripken the day his streak ended?)

The next night in Toronto, Cal Ripken was back in the lineup. He played in about half the games in the next two seasons. Then, in 2001, at age 40, he appeared in three-quarters of the Orioles games before quietly retiring — but not from baseball. He remains active as a minor league club owner and benefactor of youth baseball.

Two quiet heroes whose achievements will not be forgotten.

NORMAN L. MACHT has written more than 35 books, the latest being “They Played the Game,” oral histories of 47 players — including nine Hall of Famers — whose careers ranged from 1912 to 1981. His website, normanmacht.com, will soon include articles written by him over the past half century.

Sources

Photos: National Baseball Hall of Fame Library