Lou Gehrig, Movie Star

This article was written by Ron Backer

This article was published in Fall 2020 Baseball Research Journal

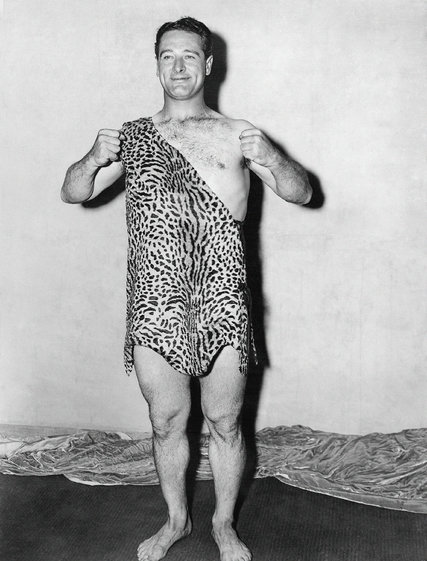

A publicity still of Lou Gehrig in Tarzan garb.

As the 1937 baseball season came to a close, Lou Gehrig was still at the top of his game. Lou had a .351 batting average that year, with 37 home runs and 158 RBIs. He was fourth in voting for the American League’s Most Valuable Player Award, having won the title the year before. Lou made his annual appearance in the 1937 All-Star Game, hitting a home run off legendary pitcher Dizzy Dean. Lou already held the major league record for playing in the most consecutive games and his streak was approaching 2,000 games. His New York Yankees won the 1937 World Series, beating the New York Giants, four games to one.

Lou commanded a high salary for ballplayers of the day.1 But with the aid of his business manager, Christy Walsh, Lou also looked for moneymaking opportunities outside the game. In prior years, these had included barnstorming tours and endorsements of products.2 Now, a new idea would be implemented—a starring role in the movies.

Hollywood Beckons

Lou first considered an appearance in a Hollywood film just after the end of the 1936 World Series.3 Independent producer Sol Lesser, who then had the rights to the Tarzan character, was looking for a new actor to play Tarzan in an upcoming movie. In the tradition of prior Tarzans Johnny Weissmuller, Buster Crabbe, and Herman Brix, Lesser was looking for a world-class athlete to play the part. He considered Ken Carpenter, the 1936 Olympic gold medalist in the discus; Larry Kelly, a Yale football star; Max Baer and Jimmy Braddock, heavyweight-boxing champions; and Sandor Szabo and Dave Levin, professional wrestlers.4

When Christy Walsh suggested to Lesser that Lou Gehrig could play Tarzan, Lesser was receptive to the idea. Before making a decision, however, Lesser wanted to see more of Lou’s body than is revealed in a baseball uniform.5 Walsh then arranged for the taking of publicity photos of Lou in jungle garb, which were sent to Lesser and also circulated to the media. The photos, not unexpectedly, met with some derision. Edgar Rice Burroughs, the author of the Tarzan stories, sent a telegram to Gehrig, which drolly read, “Having seen several pictures with you as Tarzan…I want to congratulate you on being a swell first baseman.”6 A few weeks later, after seeing the publicity photos, Lesser nixed the idea of Gehrig as Tarzan, commenting that Gehrig’s legs were “a trifle too ample” for the role.7 The part went to Glenn Morris, another Olympic champion, and the proposed film became Tarzan’s Revenge (1938).8

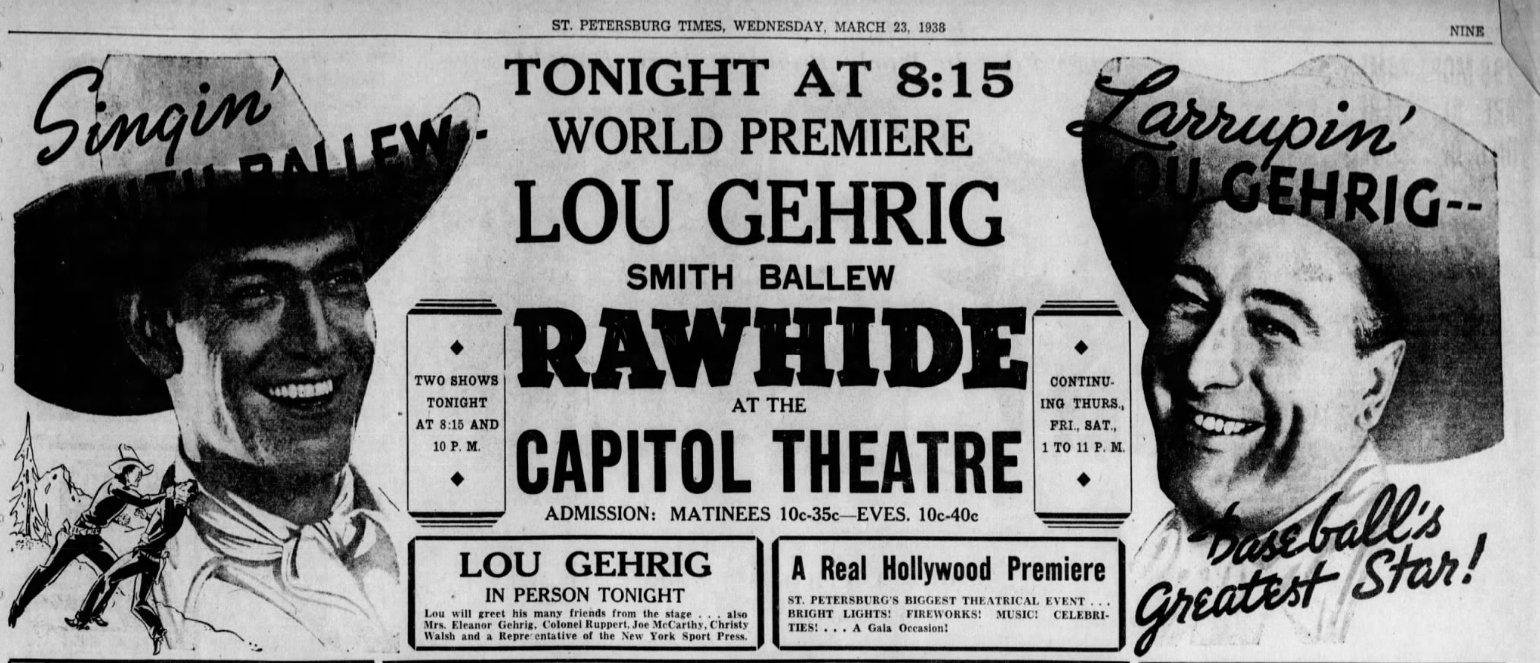

An ad for the premiere of Lou Gehrig’s Rawhide (St. Petersburg Times, March 23, 1938)

Despite the Tarzan disappointment, Sol Lesser retained an interest in Lou as an actor and box office draw. In March 1937, Lou flew to Hollywood for a screen test for Lesser. Afterwards, the parties announced that Lou had agreed to a one-picture deal with Lesser’s studio, Principal Productions. No details of the contract were disclosed. Lou was quoted at the time as saying, “I know I’m no actor, but I am going to give ’em my best.”9

The film turned out to be a B Western titled Rawhide. The movie started production on January 17, 1938, primarily at the Morrison Ranch near Agoura, California, about thirty miles from Hollywood.10 Reflecting the short shooting schedule of B movies, filming completed in early February 1938, about three weeks later.11 Lou’s wife Eleanor accompanied Lou on the trip.12 In an interview during production, Gehrig said, “Boy, I never had so much fun in my life as I’m having on this picture. … You ought to see me in my boots and saddle and ten-gallon hat.”13 Gehrig purportedly made $2,500 per week during filming.14

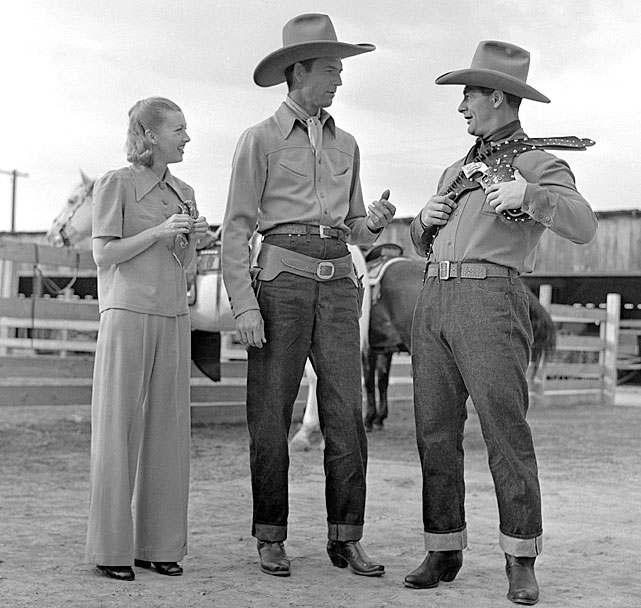

While Lou Gehrig was the obvious draw for the making of Rawhide, the producers knew even though Lou was playing himself in the film, he did not have the acting skills to carry a feature-length (58 minutes) movie on his own. Other experienced performers were brought in to assist. The top-billed performer in the movie is Smith Ballew, a Texas native who entered show business in the 1920s, quickly becoming a well-known singer, leader of his own band, and a recording artist. By 1935, Ballew was a regular on the radio and in 1936, he appeared in his first feature film. When producer Sol Lesser decided to do a series of Westerns with a singing cowboy, he chose Ballew as his leading man. It turned out that there would only be five films in the series, the fourth being Rawhide.15

Evalyn Knapp, an experienced B movie actress, plays Lou Gehrig’s sister, Peggy. Most of the heavies are familiar faces, such as Cy Kendall as the crooked sheriff and Dick Curtis as a henchman. The most recognizable actor in the film, though, is probably Si Jenks, who plays Pop Mason, the bewhiskered and toothless old codger who assists Lou in the movie. Jenks was a character actor who appeared in numerous films over the years, including many Westerns.

Christy Walsh received an unusual mention in the film’s credits: “Lou Gehrig by Arrangement with Christy Walsh.” According to The Hollywood Reporter, this was the first time that a manager received screen credit in a motion picture.16

The Film

Rawhide is a fairly standard B Western, in a modern setting, with Lou Gehrig and his sister Peggy buying a ranch out West near the town of Rawhide, which is tightly controlled by a criminal enterprise known as the Ranchers Protective Association. The Association, by threats and force, coerces the area’s ranchers into paying high dues, buying supplies from the Association at inflated prices, and turning over a part of their profits to the combine. Local attorney Larry Kimball has been fighting the Association for some time, with little success, but with the arrival of Lou Gehrig, he now has an ally in his fight to clean up the area. After the usual fisticuffs, gunfights, and chase scenes, along with standard characters such as a crooked sheriff, thug-like henchmen, and an old-codger sidekick, Larry and Lou clean up the town, providing a happy ending for its citizens and the movie’s viewers.

While Rawhide is routine, at best, it is the presence of Gehrig in the cast that distinguishes the film from standard B Westerns of the era. Gehrig was not simply thrown into the film for his name value and nothing else. Instead, scenes and dialogue were written especially for him, giving the movie a special flavor. For example, in a fight in a bar, Gehrig, recognizing that his pugilistic skills may not be up to Western standards, foregoes punches and instead throws pool balls at the bad guys, knocking many of them out and winning the fight. Who knew that baseball-throwing skills could be so important in the New West? Actually, Gehrig seems a little out-of-practice early in the scene, as he breaks windows and bottles in the bar, but once warmed up, he is very accurate.

Later, as Peggy Gehrig is about to sign a contract with the Protective Association on the second floor of a building, bandits on the ground floor prevent Lou from entering the building to stop her. Lou goes to the back of the building and sees some kids playing baseball. He borrows a bat, and fungoes a ball through the narrow second floor window, breaking the glass and preventing Peggy from signing. Who knew that baseball-hitting skills could be so important in the New West? Gehrig accomplishes this feat on his first try, contrasted with his throwing skills with the pool balls, suggesting that Lou may have been a better hitter than a fielder.

There is also self-deprecating humor inserted into the movie at the expense of Gehrig. Trying to mount a horse for the first time, Gehrig and his rear end quickly find the ground. All Lou can say is, “Strike One.” Once Gehrig finally goes out for his first ride, he finds that bouncing on the saddle is very painful for his Eastern posterior. There is even some modern satire. Saunders, the lead villain, threatens Gehrig, saying, “You’re not in New York now,” to which Gehrig responds, “For a minute, I thought I was.” Saunders also tells him, “You don’t want to be a holdout, do you?” to which Lou replies, “Well, I’ve been a holdout before.” The latter retort is a reference to some pre-season contract disputes that Lou had with the Yankees, including one before the 1928 baseball season.17, Another resulted in him missing several spring training games in 1937.18 (Lou never had a holdout during the regular season.)

The three stars of Rawhide, (L to R): Evalyn Knapp, Smith Ballew, and Lou Gehrig.

As to Gehrig’s performance, while he wasn’t the natural in front of a camera that Babe Ruth was, Gehrig gives an acceptable performance in the film, delivering his lines with all of the sincerity he can muster. Rawhide was not Shakespeare in the Park and the movie did not require the greatest of performances to be effective. In fact, Variety gave Gehrig a good review, commenting that he “can act, and should his baseball career come to an end, he might develop into another Bill Boyd or Buck Jones type.”19 Newsweek wrote, “Fully dressed from sombrero to spurs, the Tarzan candidate [Gehrig] photographs well and handles an important role with assurance.”20 Unfortunately, Gehrig’s hometown newspaper, The New York Times, was less enthusiastic, opining, “The Iron Man appears to be painfully conscious of the fact that acting is one of his lesser accomplishments.”21 Generally, however, Gehrig received good reviews for his screen performance.

It turns out that Lou Gehrig was not just a ballplayer and a cowboy star, he was also a singing cowboy. There are four songs sung in the film, with Smith Ballew carrying the heavy load on three of them.22 Lou, while riding in a wagon, gets a chance to sing a few verses of one of the songs, “A Cowboy’s Life.” Those verses are specific to Lou’s experiences in the West. For example, Lou warbles the following lyrics: “Oh, the city cowboy had his fun/So I took my bats/I traded them for riding boots and seven gallon hats.”

Lou has a surprisingly good singing voice in the movie, but, of course, it is not really Lou singing. Buddy Clark, a popular singer of the 1930s and ’40s who sometimes dubbed other actor’s voices, dubbed Lou’s voice.23 Lou’s “singing” in the film continued a practice of Yankees Hall-of-Famers singing in the movies. In addition to Lou Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio sang a bit of a song in Manhattan Merry-Go-Round (1937) and Babe Ruth talked his way through a song in Home Run on the Keys (1937).

Release and Promotion

The premiere of Rawhide took place on March 23, 1938, in St. Petersburg, Florida, then the home of the New York Yankees’ spring training facilities. The festivities included a parade down Central Avenue, a marching band, and fireworks. Yankees owner Colonel Ruppert, manager Joe McCarthy, Eleanor Gehrig, Christy Walsh, and players from the New York Yankees and the St. Louis Cardinals, who also trained in St. Petersburg that year, were present for the event. Al Schacht, the famous baseball clown, rode a trick bicycle. The Oklahoma Mud Cat band, composed of several St. Louis Cardinals players—including its leader, outfielder Pepper Martin—played hillbilly music for the crowd.24 According to a newspaper report, thousands of the curious thronged the streets to get a glimpse of the celebrities of the sports world.25

The opening, which took place at the Capitol Theater, was advertised as “A Real Hollywood Premiere.”26 At the entrance, there was a red carpet, Klieg lights, and a microphone for anybody who had something to say.27 Inside the theater, Lou gave a speech to the fans in attendance, saying, “People think I’m modest when I say I’m lucky. I’m not—I am lucky, and if anyone wants to argue with me about it, I’ll stand and argue with him about it all day.”28 That would not be the last time in Lou Gehrig’s life that he referred to himself in a speech as lucky.

Rawhide premiered in New York City at the Globe Theater in midtown Manhattan on Saturday, April 23, 1938. Although there was no Hollywood-style opening, Gehrig and his teammates made a personal appearance at the theater on the evening of Sunday, April 24, 1938, after beating the Washington Nationals earlier that day, 4-3.29

The Life of Lou Gehrig

For those who are familiar with the facts of Lou Gehrig’s life, there are some strange moments in Rawhide. Lou quits baseball at the beginning of the film and returns to baseball at the end of the film, but surprisingly never mentions the New York Yankees by name. In real life, Lou never had a sister named Peggy. In fact, Lou Gehrig did not have any siblings who survived childhood.30 Lou was married to Eleanor at the time the movie was made, but she is never mentioned in the film. In this fictionalized version of Lou’s life, there is no reference to Lou being married.

Of course, the fictional character of Peggy was inserted into the film to provide Larry Kimball with a mild love interest. If Eleanor had bought the ranch with Lou in the movie, Rawhide would have been bereft of a romantic subplot, a B Western staple.

While not true at the time of the film’s release in 1938, Rawhide now has a form of dramatic irony. As a result of the disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Gehrig played his last regular season game of baseball in real life on April 30, 1939. Thus, Gehrig was through with baseball only about a year after the first showing of Rawhide in New York City. Accordingly, when Gehrig tells the reporters at the beginning of the film, “Take it or leave it. I’m through with baseball,” those lines now take on added meaning. Also, because of the quick onset of ALS, some viewers may scrutinize the film to see if there are any signs of Gehrig’s oncoming disease. They would conclude, as seems apparent, that Gehrig was in excellent health during the filming of the movie. In fact, he lifts a henchman over his head in the fight scene in the bar and leaps over a porch chair in the film’s concluding scene.31

The End of a Film Career

Rawhide contains Lou Gehrig’s only role in films.32 Although not disclosed at the time of the signing of Gehrig’s contract in March of 1937, Principal Productions apparently negotiated an option for the use of Gehrig in an additional movie. The studio let that option lapse in October of 1938, with Sol Lesser announcing that going forward, he was only interested in making kids pictures.33 Whether another studio may have been interested in working with Lou will never be known as, by then, Lou was already showing the first signs of the disease that eventually took his life.34

RON BACKER is an attorney who is an avid fan of both movies and baseball. He has written five books on film, his most recent being Baseball Goes to the Movies, published in 2017 by Applause Theatre & Cinema Books. A long-suffering Pirates fan, Backer lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Feedback is welcome at rbacker332@aol.com.

Sources

Photos courtesy of Ron Backer.

Notes

1 The New York Times reported that Lou’s salary for 1937 was $36,000 plus a signing bonus of $750. James P. Dawson, “Two-Gun Gehrig, Movie Job Ended, Turns Thoughts to Baseball,” New York Times, February 3, 1938, 27. This is confirmed by “Training Camp Notes,” The Sporting News, March 25, 1937, 8.

2 Gehrig did ads for Camel cigarettes and Aqua Velva. He was the first athlete to have his face on a Wheaties box. Louis Menand, “How Baseball Players Became Celebrities,” The New Yorker, June 1, 2020, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/06/01/how-baseball-players-became-celebrities.

3 “Gehrig Seeks Role as Tarzan in Films,” Associated Press, New York Times, October 21, 1936, 40.

4 Scott Tracy Griffin, Tarzan on Film, (London, UK: Titan Books, 2016), 58.

5 Dan Joseph, Last Ride of the Iron Horse (Mechanicsburg, PA: Sunbury Press, 2019), 10.

6 “Author Ridicules Gehrig as Tarzan,” Atlantic Constitution, November 19, 1936, 12.

7 Jonathan Eig, Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2005), 220.

8 Eig, 219-220. Morris won the gold medal in the decathlon in the 1936 Olympic games in Berlin.

9 Bob Ray, “Lou Hits the Screen,” The Sporting News, March 11, 1937, 5.

10 Joseph, 26.

11 American Film Institute Catalog of Feature Films (“AFI”), Rawhide, https://catalog.afi.com/Film/5451-RAWHIDE?sid=e3fb05f4-1f85-4e26-a54e-414249ec5c70&sr=0.8563489&cp=1&pos=4.

12 Bob Ray, “‘Two-Gun’ Lou Gehrig Stars as Rootin’,Tootin’, Shootin’ Hero of the Wild West,” The Sporting News, January 27, 1938, 10.

13 Ray, “‘Two-Gun’ Lou Gehrig.”

14 Joseph, 24, 26.

15 Don Creacy, “Smith Ballew,” Classic Images, posted June 2, 2010, http://www.classicimages.com/people/article_6a695f92-3a23-5fba-89d6-87cf2e422bf2.html

16 “Ghost Shreds Shroud,” Hollywood Reporter, January 21, 1938, 2. Christy Walsh was never afraid to promote himself. In the 1930s, he produced several short subjects, including a five film series with Babe Ruth, with the overall title, “A Christy Walsh All America Sportreel.” In The Pride of the Yankees (1942), he received mention in the film as follows: “Appreciation is expressed for the gracious assistance of Mrs. Lou Gehrig and for the cooperation of Mr. Ed Barrow and the New York Yankees arranged by Christy Walsh.”

17 James Lincoln Ray, “Lou Gehrig,” SABR Biography Project. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/ccdffd4c.

18 Richard Hubler, Lou Gehrig: The Iron Horse of Baseball (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1941), 174; “Training Camp Notes,” The Sporting News, March 25, 1937, 8.

19 Variety, April 6, 1938, 14. William “Bill” Boyd and Buck Jones were stars of many B movie Westerns, with Boyd playing Hopalong Cassidy in a series of films.

20 “Baseball’s Iron Man Fails as Tarzan But Qualifies as Western Two-Gun Hero,” Newsweek, April 18, 1938, 24.

21 New York Times, April 25, 1938, 19.

22 Albert Von Tilzer, the man who composed “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” composed two of those songs.

23 Eig, 238.

24 Ray Robinson, Iron Horse: Lou Gehrig In His Time (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.: 1990) 231-232; Eig, 242; “Lou Gehrig’s Film in World Premiere Here Tonight,” St. Petersburg Times, March 23, 1938, 8.

25 Jack Thale, “Premiere Here Honors Gehrig,” St. Petersburg Times, March 24, 1938, 6.

26 St. Petersburg Times, March 23, 1938, 9.

27 Gayle Talbot, “St. Louis and New York Players See Lou Gehrig’s New Moving Picture,” Tampa Daily News, March 24, 1938, 14.

28 Thale, 6.

29 Advertisement for Rawhide, New York Times, April 23, 1938.

30 An older sister Anna died when she was just three months old. Another sister, Sophie, died when she was less than two years old and an unnamed brother died almost immediately after birth. James Lincoln Ray, “Lou Gehrig,” SABR Biography Project. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/ccdffd4c.

31 According to an article published in 2007 in Neurology, a scientific journal, a careful examination of Rawhide by medical professionals disclosed that Lou functioned normally in January 1938, when the film was shot. No evidence of hand atrophy or leg weakness appears in the movie. Melissa Lewis and Paul H. Gordon, “Lou Gehrig, Rawhide, and 1938,” 68 Neurology, February 20, 2007, 615-618.

32 In Speedy (1928), his only other screen appearance, Lou photo bombed a scene outside Yankee Stadium with Harold Lloyd and Babe Ruth. Lou appears in the background of the scene for only a second or two. He has no dialogue.

33 “Lesser Benches Gehrig,” Variety, October 5, 1938, 5.

34 Joseph, 137.