Lou Gehrig’s Farewell Speech: July 4, 1939

This article was written by Paul Hofmann

This article was published in Yankee Stadium 1923-2008: America’s First Modern Ballpark

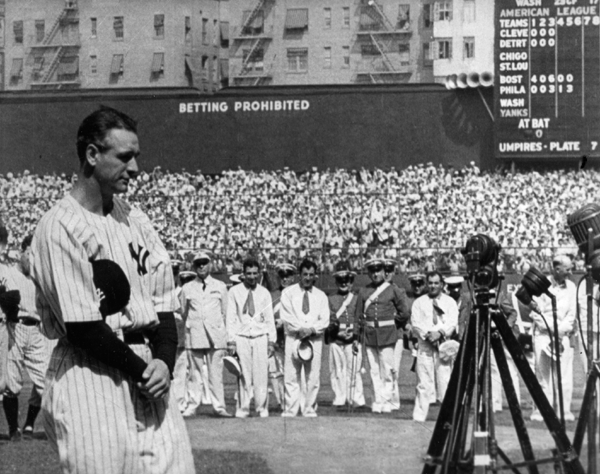

A packed crowd of 61,808 fans heard Lou Gehrig make his “Luckiest Man” speech between games of a doubleheader against Washington. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

Lou Gehrig played his final game for the New York Yankees on April 30, 1939. Though only 35 years old, the Iron Horse, who played in 2,130 consecutive games, had been diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).1 To honor their stricken star, the Yankees held Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day on July 4, 1939.

The Independence Day doubleheader pitted the sixth-place Washington Senators, who entered play with a 28-42 record, 24½ games off the pace, and the three-time defending World Series champion New York Yankees, who were 51-16, 12½ games clear of the second-place Boston Red Sox. The games were overshadowed by the ceremony that took place between them. It was Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day and 61,808 fans jammed into Yankee Stadium to pay homage to the Yankees’ ailing star.

While Gehrig dressed in the clubhouse, some of his old teammates dropped in to say hello, including Mark Koenig, Wally Schang, Herb Pennock, Bob Shawkey, Benny Bengough, George Pipgras. Tony Lazzeri, Earle Combs, Joe Dugan, Waite Hoyt, Bob Meusel, Everett Scott, and Wally Pipp, who faded away as the Yankees’ first baseman the day Gehrig took over back in 1925.2 Missing from the clubhouse was Babe Ruth. Ruth had yet to arrive and, given Ruth and Gehrig’s relationship, everyone wondered whether the Bambino would show up.

Ruth and Gehrig couldn’t have been more different. Ruth was a brash and boorish free spirit who had a casual and often defiant way of dealing with authority. He was also fun-loving and charismatic, with an ego that craved the spotlight. By contrast, Gehrig was modest and reserved, avoiding public attention. He was the consummate company man. Given these differences, it seemed unlikely that a relationship beyond the playing field would have materialized.3 However, a close relationship between the two did develop and from the very beginning it was complicated.

In the early years, Ruth was a mentor whom Gehrig idolized. Columbia Lou never believed that he could be Ruth’s equal. “The only real home run hitter that has ever lived,” Gehrig once said in reference to Ruth. “I’m fortunate to be even close to him.”4 The two developed a close relationship. Sharing confidences, eating, traveling and barnstorming together, playing cards, swapping batting tips, fishing and golfing together, Ruth and Gehrig should have grown closer with the passing years.5 Instead they grew apart and the relationship entered a period of estrangement, when each refused to speak to the other.

In the opener of the doubleheader, the Senators scored two first-inning runs in support of right-hander Dutch Leonard (8-2), who limited the Yankees to six hits and helped his own cause with a sixth-inning RBI single. Right-hander Monte Pearson (7-2) suffered the loss for Yankees, who managed a single run in the third and another in the ninth on a one-out home run by right fielder George Selkirk as the Senators hung on for a 3-2 victory.

Ruth arrived in plenty of time for the ceremony, wearing a cream-colored suit and looking tanned and rested. By the late 1930s, Ruth had ballooned to 270 pounds and was beginning to experience some health problems of his own.6

After the first game, microphones were set up behind home plate for the ceremony. Sid Mercer, dean of beat reporters covering the Yankees, served as emcee for the event. New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia officially extended the city’s appreciation of the service Gehrig had given to his hometown. The mayor praised Gehrig as “the greatest prototype of good sportsmanship and citizenship.”7 Postmaster General James Farley, also in attendance, concluded his remarks with “for generations to come, boys who play baseball will point with pride to your record.”8

Ruth then took a turn at the microphone. Though their relationship had been troubled, Ruth never held a grudge and seemed happy to be reunited with his old friend. In his own blustering style, Ruth gave his unqualified opinion that the 1927 Yankees were better than the 1939 edition. Summarizing his belief, Ruth said, “In 1927 Lou was with us, and I say that was the greatest ballclub the Yankees ever had.”9 The Sultan of Swat continued, “I know Lou is going to keep that stiff upper lip and he’s gonna keep on going.”10

Mercer then introduced Gehrig to the huge throng in attendance and millions listening on radios across the country. Head bowed, Gehrig stood silent until he privately whispered something to Mercer, who returned to the microphone and told the crowd and listening audience, “Lou has asked me to thank you all for him. He is too moved to speak.”11 The response to Mercer’s remark was chants of “We want Gehrig!” throughout the ballpark.12

As the chants continued, Gehrig took a handkerchief from his pocket, wiped away his tears and moved toward the microphones once again. Head bowed, he spoke slowly and evenly as he delivered the most memorable farewell speech in baseball history. While no complete recording or transcript of the speech is known to exist, one commonly accepted version is as follows:

“Fans, for the past two weeks you have been reading about the bad break. Today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth. I have been in ballparks for seventeen years and have never received anything but kindness and encouragement from you fans.

“When you look around, wouldn’t you consider it a privilege to associate yourself with such a fine looking men as they’re standing in uniform in this ballpark today? Which of you wouldn’t consider it the highlight of his career just to associate with them for even one day? Sure, I’m lucky. Who wouldn’t consider it an honor to have known Jacob Ruppert? Also, the builder of baseball’s greatest empire, Ed Barrow? To have spent six years with that wonderful little fellow Miller Huggins? Then to have spent the next nine years with that outstanding leader, that smart student of psychology, the best manager in baseball today, Joe McCarthy? Sure, I’m lucky.

“When the New York Giants, a team you would give your right arm to beat, and vice versa, sends you a gift – that’s something. When everybody down to the groundskeepers and those boys in white coats remember you with trophies – that’s something. When you have a wonderful mother-in-law who takes sides with you in squabbles with her own daughter – that’s something. When you have a father and a mother who work all their lives so you can have an education and build your body – it’s a blessing. When you have a wife who has been a tower of strength and shown more courage than you dreamed existed – that’s the finest I know.

“So I close in saying that I might have been given a bad break, but I have an awful lot to live for. Thank you.”13

Like many in attendance, Ruth was moved to tears by Gehrig’s brief speech. The Babe went over to shake his old friend’s hand but impulsively put his arm around Gehrig and hugged him – ending the long-standing and petty feud between them.14 It was the first time Gehrig cracked a smile all day. As they embraced, a tearful Ruth couldn’t have imagined he would be facing a similar crowd under very similar circumstances less than a decade later.

After the ceremony, Gehrig returned to the clubhouse, where he saw right-hander Steve Sundra, who was slated to start the nightcap for the Yankees. Gehrig went to Sundra and said, “Big Steve, win the second game for me, will ya?”15

Sundra (5-0) delivered a six-hit complete game and the Yankees scored six runs in the first three innings off Venezuelan rookie right-hander Alex Carrasquel (4-6) on their way to an 11-1 victory. Selkirk paced the Yankees’ hitting attack with three hits, including a home run, while second baseman Joe Gordon drove in four runs for the Yankees. Right fielder Taffy Wright accounted for the Senators lone run with a second-inning home run.

On June 2, 1941, Gehrig died at his home.

PAUL HOFMANN has been a SABR member since 2002 and contributed to more than 25 SABR publications. Paul is the assistant vice president for the International Center at the University of Louisville and teaches in the College of Management at National Changhua University of Education in Taiwan. A native of Detroit, Paul is an avid baseball card collector and lifelong Detroit Tigers fan. He currently resides in Lakeville, Minnesota.

SOURCES

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

NOTES

1 Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, commonly known as ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease, is an incurable fatal neuromuscular disease. The disease attacks nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. Motor neurons, which control the movement of voluntary muscles, deteriorate and eventually die. When the motor neurons die, the brain can no longer initiate and control muscle movement. Because muscles no longer receive the messages they need in order to function, they gradually weaken and deteriorate, resulting in paralysis.

2 John Drebinger, “61,808 Fans Roar Tribute to Gehrig: Chief Figure at the Stadium and Old-Time Yankees who Gathered in His Honor,” New York Times, July 5, 1939: 21.

3 Jonathan Eig. Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005), 97.

4 Eig, 100.

5 Ray Robinson, “Ruth and Gehrig: Friction Between Gods,” New York Times, June 2, 1991: 394.

6 Ruth experienced the first of two heart attacks while playing golf in 1939.

7 Drebinger, “61,808 Fans Roar Tribute to Gehrig.”

8 Drebinger.

9 Eig, 315.

10 July 4, 1989-Tigers vs. Yankees (WPIX-Part 2), www.youtube.com/watch?v=uhUL-ff8NQw (accessed August 15, 2022).

11 Rosaleen Doherty, “Wife Brave, Lou Shaken as 61,000 Cheer Gehrig,” New York Daily News, July 5, 1939: 120.

12 Doherty.

13 Transcript adapted from “Farewell Speech,” lougehrig.com/index.php/farewell-speech/.

14 Robert Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1974), 415.

15 “Pages Out of the Past,” Atlantic City Evening Union, January 18, 1952, as cited by David Skelton, “Steve Sundra,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/3c2f6fad.