Major-League Players Who Wore Glasses

This article was written by David A. Goss

This article was published in 2008 Baseball Research Journal

You can’t hit it if you can’t see it. Success in baseball requires good visual skills, including being able to see clearly. Many people need glasses or contact lenses. The most common reason for using them before age 40 is myopia (nearsightedness), which affects 20 to 30 percent of young adults in the United States.1,2 The percentage of major-league ballplayers who have played in glasses is far lower. In this article I will discuss data on the use of glasses by major-league players, possible reasons for fluctuations in their numbers over the years, and some firsts and miscellaneous facts on the use of glasses by ballplayers.

You can’t hit it if you can’t see it. Success in baseball requires good visual skills, including being able to see clearly. Many people need glasses or contact lenses. The most common reason for using them before age 40 is myopia (nearsightedness), which affects 20 to 30 percent of young adults in the United States.1,2 The percentage of major-league ballplayers who have played in glasses is far lower. In this article I will discuss data on the use of glasses by major-league players, possible reasons for fluctuations in their numbers over the years, and some firsts and miscellaneous facts on the use of glasses by ballplayers.

NUMBERS OF PLAYERS WHO HAVE WORN GLASSES

Sources that I have used to identify major-league players who wore glasses include various articles on the subject,3-6 photos in publications and on the Internet, observation of telecasts, postings on SABR-L, e-mail communications from SABR members, and particularly a list compiled by baseball researcher Karl Priest. Priest has been compiling it for about twenty years. His criteria for including a player are an authoritative reference that the player wore or tried glasses, a photograph of a player in uniform wearing glasses, or observation of a player in uniform on television wearing glasses. I have used the same criteria in adding a few players to the list. As of December 2005, the total stands at 431. Given that 16,003 players played in the major leagues from 1871 through 2003,7 those who wore glasses constituted less than 3 percent of the total.

To determine how the use of eyeglasses by ballplayers has changed over the years, I found the year in which each player who wore glasses made his major-league debut.8,9 I also recorded for each one the position he played most often in his career.

Major-leaguers who wore glasses were rare before 1920. The only nineteenth-century player was William White,10 who pitched until 1886. It would be another 29 years before another major-leaguer would wear glasses—Lee Meadows in 1915. From 1915 to 1919, he was joined by Carmen Hill and Norman Plitt.

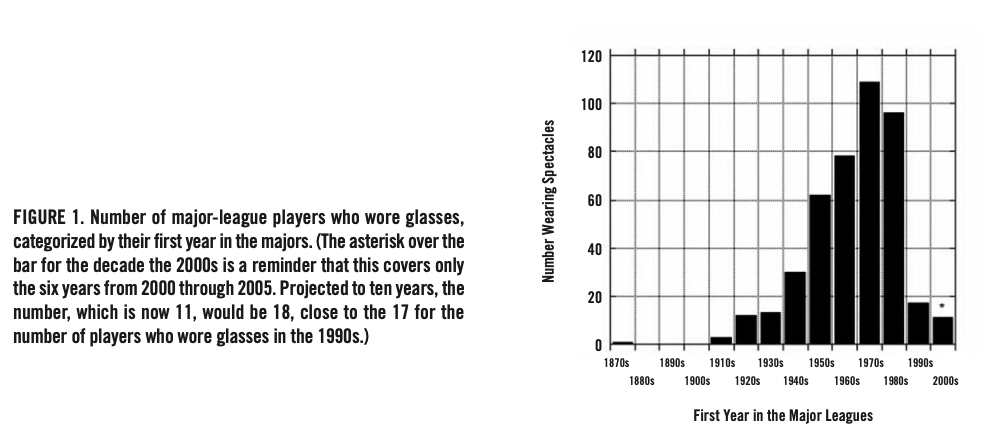

As shown in the accompanying figure, the number of glasses-wearing players beginning their major-league careers increased each decade from the 1920s through the 1970s. Thirty debuted in the 1940s, 62 in the 1950s, 78 in the 1960s, and in the 1970s the number peaked to more than a hundred. There were 96 in the 1980s. It dropped to 17 in the 1990s, and so far there have been 11 who debuted between 2000 and 2005. The increase from the 1960s to the 1970s may be accounted for in part by league expansion. The drop in the 1990s is even more dramatic when we take into account that the decade saw further expansion. It is possible that there will be a few additions to the list for the 1990s and the first decade of the twenty-first century—some of the players who debuted in those years may start wearing glasses later in their careers.

I classified the players by when they began their major-league careers rather than the time (much more difficult to confirm) when they started wearing glasses. It is likely that most of these players wore glasses when they debuted. Among the known exceptions are Paul Waner, who started wearing glasses on the field at age 37 in 1940; Boom-Boom Beck, at age 33 in 1938; and Mel Ott, at age 31 in 1940.

Of the 430 who began their major-league careers between 1910 and 2005, 174 (40 percent) were pitchers, 35 (8 percent) catchers, 121 (28 percent) infielders, and 100 (23 percent) outfielders. No position appears to be significantly represented more than the others. I compared those percentages to the percentages for players whose last names begin with A and B and who debuted between 1910 and 2003.8 Of those, 47 percent were pitchers, 8 percent catchers, 25 percent infielders, and 20 percent outfielders—percentages fairly close to those for the players who wore glasses and not significantly different by the chi-square statistic.

(Click image to enlarge)

POSSIBLE EXPLANATIONS FOR FLUCTUATIONS IN THE NUMBERS

The spectacle lenses of the 1910s and 1920s were much more prone to breakage than are the lenses of today, and the frames used then were not as sturdy. The lenses in common use were glass. There were no minimum standards for thickness, and the thin glass lenses of that era were easily broken. Splinters of glass from broken lenses represented a significant risk for eye injury. Players of that time—Meadows, Hill, George Toporcer—all indicated that their glasses occasionally broke on the field. It is likely that youngsters of that era who wore glasses were discouraged from playing baseball. Meadows was warned that baseball was “a brave but foolhardy career for one so afflicted.”12 And it has been reported that, because he wore glasses, Toporcer was not allowed to try out for his seventh-grade baseball team.13

In 1928, F. C. Lane wrote that

owners and managers and coaches, for at least two baseball generations, placed the young fellow who wore glasses in quite as hopeless a category as though he used crutches. For the mere wearing of glasses argued defective vision—the insurmountable barrier It is interesting, though quite useless, to speculate on how many capable ball players have been prevented from engaging in a baseball career during the past fifty years simply because they were obliged to wear glasses. Unquestionably the number is considerable.4

Lane went on to discuss the players of that era who wore glasses—Meadows, Hill, Josh Billings, and Dan MacFayden—and how they conquered the notion that wearing glasses was a “hopeless handicap to a ball player” and how they “paved the way” for others.

Improvements in the impact resistance of spectacle lenses coincided with a rise in the number of players who wore glasses. In the mid-twentieth century, heat tempering to strengthen glass lenses was introduced, and minimum thickness standards were established. In the 1950s, resin plastic lenses became more readily available. They did not break as easily as glass, and when they did break they were not as dangerous because they were less likely to shatter into small fragments. Late in the twentieth century, polycarbonate lenses were developed, their advantage being that they were more impact-resistant than either glass or plastic. Improved safety of spectacle lenses was probably a major reason for the rise in the number of players who wore glasses from the 1910s through the 1970s.

Another reason may have been a change in the attitudes of players. One often hears stories of early-twentieth-century players hiding physical infirmities or injuries for fear of losing their jobs. Oliver Abel in 1924 observed that “players are so much afraid their managers will discover that they ought to be using glasses that they refuse to wear them even off the field.”3 By 1960, however, Ralph Ray would comment that “although nowadays glasses are taken for granted by scouts, it wasn’t until the last decade or so that players dared walk onto the diamond with specs, even if they needed them.”6

For players looking for any edge to improve performance, the stigma of wearing glasses disappeared some time ago. One optometrist told me the story of a recent major-league player with a slight astigmatism, at a level that is usually left uncorrected because the improvement in visual acuity would be minimal. The player insisted on getting glasses because he thought that the tiny improvement in clarity of vision might help him in game situations.

Undoubtedly the reason for the decline in the use of glasses in the 1980s is the popularity of soft contact lenses. Rigid contact lenses became widely available in the 1950s. However, they did not work well for ballplayers, for several reasons—glare, sensation of lens movement, discomfort from dust getting under the lenses, and the small hard lenses were easily lost.14 Players including Roy McMillan and Lee Walls tried rigid contact lenses and went back to glasses.14 Soft contact lenses became available in the early 1970s. By the mid-1970s it was becoming clear that they were a good solution to the problems ballplayers experienced with hard lenses.15

More recently, refractive surgery, which reduces or eliminates dependence on glasses or contact lenses, has contributed to the further decline in the use of glasses by players. Laby et al. found that seventeen position players had been identified in the public media as having had laser refractive surgery. They include Al Martin, Greg Vaughan, Mike Lansing, Bernard Gilkey, Jeff Bagwell, Wally Joyner, Jose Cruz, Bernie Williams, Todd Dunwoody, Trot Nixon, Frank Catalanotto, and Larry Walker. Of those twelve, Laby et al. compared the before-surgery and after-surgery batting averages, on-base percentages, slugging percentages, and on-base plus slugging (OPS). They concluded that the “preliminary data do not show a loss in performance after the refractive surgical procedure.” However, they added, while unaided visual acuity after surgery may be improved enough for everyday activities without glasses, correction of small residual refractive conditions left after the procedure might still help a ballplayer’s performance. They also noted that “the risk of a complication,” (e.g., postoperative glare, halos, loss of best corrected visual acuity) “with the potential to end a player’s career” is minimal but “real and likely not worth assuming without a scientifically documented on-field hitting benefit to undergoing the surgical procedure.”16

SOME FIRSTS AND SOME MISCELLANEOUS FACTS

The first major-league player to wear glasses on the field was William H. White, a right-handed pitcher in the National League and American Association (1877—86). He led the American Association in wins in 1882 and 1883. After he retired from baseball, White became an optician and founded the Buffalo Optical Company.17

The first major-league player to wear glasses on the field was William H. White, a right-handed pitcher in the National League and American Association (1877—86). He led the American Association in wins in 1882 and 1883. After he retired from baseball, White became an optician and founded the Buffalo Optical Company.17

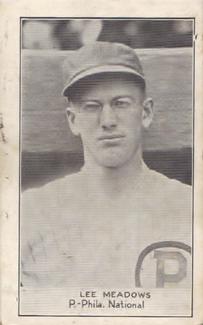

The first twentieth-century major-leaguer to play in glasses was Lee Meadows, who pitched for three National League teams, St. Louis (1915—19), Philadelphia (1919—23), and Pittsburgh (1923—29). He finished his career at 188—180 with a 3.37 ERA. In 1916 he pitched in 51 games to lead the league, and he tied for the league lead in wins (20) in 1926 and in complete games (25) in 1927. His nickname was “Specs.” In close-up photographs his eyes appear small through his spectacle lenses, suggesting that he had myopia (nearsightedness). Lenses for the correction of myopia minify, so that the eyes look smaller through them. In contrast, lenses correcting hyperopia (farsightedness) magnify, making a person’s eyes appear large through their glasses.

Carmen Hill, the next player to wear glasses, made his major-league debut late in the 1915 season. He pitched in the majors parts of ten seasons through 1930, going 49—33 with a 3.44 ERA. Of those 49 wins, 22 were in 1927, and 16 in 1928. As teammates on the pennant-winning Pittsburgh Pirates in 1927, Hill and Meadows combined for 41 wins. Hill had a long minor-league career, during which he went 202—162.18 Photographs of him suggest that he was nearsighted but probably not as nearsighted as Meadows. Hill started wearing glasses when he was 14 years old, and he later recalled that his glasses broke on the field on several occasions.19,20 One of his nicknames was “Specs.”

The first position player to wear glasses on the field was George “Specs” Toporcer (born Toporczer). In 546 games as a utility infielder for the St. Louis Cardinals (1921—28), he had a .279 batting average, .347 on-base percentage, and .373 slugging percentage. His best year was 1922, when he had a .324 batting average with 25 doubles in 116 games. In the majors the position he played most often was shortstop. After his years with the Cardinals, he played second base for Rochester on four consecutive International League championship teams. As a player and manager, Toporcer was named to the International League Hall of Fame. He is reported to have broken his glasses several times on bad-bounce ground balls. Photographs of Toporcer suggest that he had moderate to severe myopia. In his early fifties he went blind after unsuccessful operations for retinal detachments,21 which were likely related to his myopia, as the risk of retinal detachment increases with the severity of the myopia. Toporcer lived to age 90, sometimes appearing as an inspirational speaker.22 He also wrote a baseball instructional book.

The first outfielder to wear glasses on the field was Charles J. “Chick” Hafey of the Cardinals (1924—31) and Cincinnati (1932—35, 1937). Various injuries and ailments limited his playing time. In only seven seasons did he play more than 100 games. He had 1,466 hits, a .317 batting average, .372 onbase percentage, and .526 slugging percentage in 1,283 career games. At .590, he led the National League in slugging percentage in 1927. In 1929, he began wearing glasses. Two years later he .349, becoming the first player who wore glasses to win a batting title. From reports in various sources, it is not clear exactly what Hafey’s eye problem was. One of his teammates was quoted as saying that without his glasses Hafey couldn’t read the large signs in railroad stations.23 That suggests myopia, but Hafey apparently had a more complicated vision problem or an additional vision problem, as he had fluctuating vision and used three different pairs of glasses.24

The first major-league catcher to play in glasses was Clint Courtney. He spent most of his 11-year career (1951—61) with the St. Louis Browns and Baltimore Orioles and the Washington Senators, but he also played a few games for the New York Yankees, Chicago White Sox, and Kansas City Athletics. The only position he played in the majors was catcher (802 games). He had four seasons in which he caught more than 100 games, three with the Browns and Orioles and one with the Senators. In 946 games, he had a .268 batting average, .341 on-base percentage, and .366 slugging percentage. The first glasses-wearing ballplayer to win a Most Valuable Player Award was Jim Konstanty in 1950. In 11 years in the majors, Konstanty pitched in 433 games, mostly in relief. He finished his career at 66—48 with a 3.46 ERA. In 1950 he pitched 152 innings in 74 games, all in relief, going 16—7 with an ERA of 2.66. Had saves been an official statistic that year, he would have led the league with 22. He was an important part in the Phillies’ successful pennant drive in 1950.

Myths about ballplayers who wear glasses are common. Stories about Ryne Duren’s poor vision and “Coke-bottle” glasses abound. An optometrist of my acquaintance said that, when he examined Duren after he had retired from baseball, he found Duren to have normal visual acuity with his glasses and only slight myopia.

Today players who wear glasses on the field are few. Some of them use sports frames. Recent and current players who wear glasses include Gustavo Chacin, Brendan Donnelly, Travis Driskill, Eric Gagne, Brandon League, Ramon Nivar, Jason Phillips, Duaner Sanchez, Ismael Valdez, and Jose Vizcaino. Ballplayers in glasses are not as common today as they were in the 1960s and ’70s, but they are more accepted now than they were a hundred years ago. When was the last time you heard a player called “Specs”?

DAVID A. GOSS is professor of optometry at Indiana University and has been a member of SABR since 1993.

Notes

- Theodore Grosvenor, “A Review and a Suggested Classification System for Myopia on the Basis of Age-Related Prevalence and Age of Onset,” American Journal of Optometry and Physiological Optics 64, no. 7 (1987): 545—54.

- Zadnik and Donald O. Mutti, “Incidence and Distribution of Refractive Anomalies,” in Borish’s Clinical Refraction, ed. W. J. Benjamin (Philadelphia: Saunders, 1998), 30—46.

- Oliver Abel, “Eyes and Baseball,” Western Optical World (1924): 401—2.

- C. Lane, “Baseball’s ‘Four-Eyes’ Celebrities,” Baseball Magazine, October 1928, 483, 484, 516.

- Hy Turkin, “Window Wearers Are Increasing—and That’s No Optical Illusion,” The Sporting News, 6 June 1940,

- Ralph Ray, “39 in Majors Wear Specs; only 6 in ’40,” The Sporting News, 6 April 1960, 3,

- John Thorn, Pete Palmer, and Joseph M. Wayman, “The History of Major League Statistics,” in Total Baseball: The Ultimate Baseball Encyclopedia, 8th ed., John Thorn, Phil Birnbaum, and Bill Deane (Toronto: Sport Media, 2004), 951—62.

- John Thorn, Phil Birnbaum, and Bill Deane, , Total Baseball: The Ultimate Baseball Encyclopedia, 8th ed. (Toronto: Sport Media, 2004), 983—2325.

- The Sporting News, 2005 Baseball Register (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 2004).

- Harold Seymour, Baseball, 1, The Early Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 1960), 326.

- Lou Hatter, “Desperate Boog Wearing Specs to Snap Bat Slump,” The Sporting News, 24 June 1972, 4.

- Neal McCabe and Constance McCabe, Baseball’s Golden Age: The Photographs of Charles Conlon (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1993), 162.

- The Sporting News, Conlon Collection, baseball card number 893 (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1993).

- George Jessen, “Baseball and Contact Lenses: Possible Solution to the Problem,” American Journal of Optometry and Archives of the American Academy of Optometry 43, no. 5 (1966): 320—24.

- David Goss, Wayne Cary, and Dan M. Holyk, “Contact Lenses for the Athlete,” Optometric Weekly 67, no. 40 (1976): 1071—73.

- Daniel M. Laby, David G. Kirschen, and Paul DeLand, “The Effect of Laser Refractive Surgery on the On-Field Performance of Professional Baseball Players,” Optometry 76, no. 11 (2005): 647—52.

- Joseph M. Overfield, “William Henry White,” in Nineteenth Century Stars, Robert L. Tiemann and Mark Rucker (Kansas City: Society for American Baseball Research, 1989), 137.

- Society for American Baseball Research, Minor League Stars, 3, Career Records of Players (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1992), 160.

- Carmen P. Hill, An Autobiography: The Battles of Bunker Hill: The Life and Times of Carmen Hill. ([Iola, Wisc.]: Krause Publications, 1985).

- Eugene C. Murdock, Baseball Between the Wars: Memories of the Game by the Men Who Played It (Westport, : Meckler, 1992), 155—85.

- Lawrence Ritter, The Glory of Their Times: The Story of the Early Days of Baseball Told by the Men Who Played It (New York: William Morrow, 1984), 259—70.

- Bill O’Neal, The International League: A Baseball History, 1884-1991 (Austin, Tex.: Eakin Press, 1992), 148.

- The Sporting News, Conlon Collection, baseball card number 889 (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1993).

- William Borst, “Chick Hafey,” in The Ballplayers: Baseball’s Ultimate Biographical Reference, ed. Mike Shatzkin (New York: Arbor House / William Morrow, 1990), 431.