Managing History: Jackie Robinson and Managers

This article was written by Joe Cox

This article was published in Jackie Robinson: Perspectives on 42 (2021)

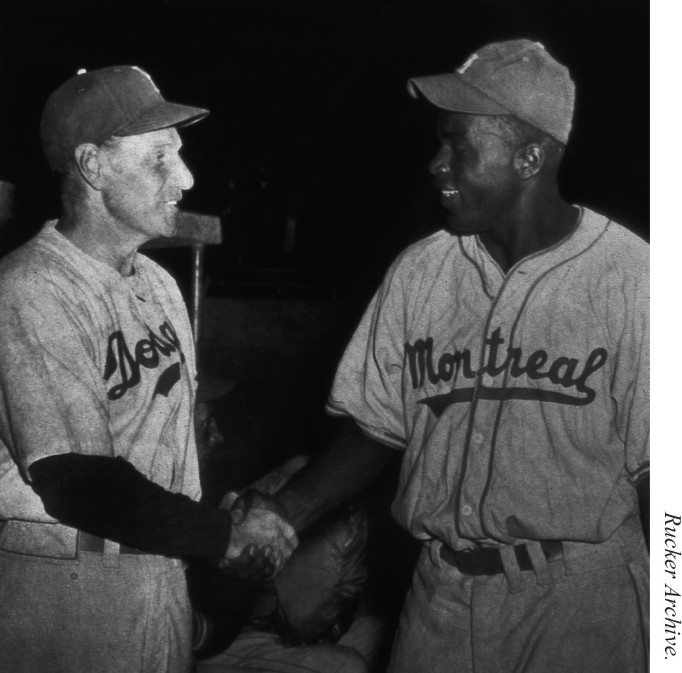

Jackie Robinson, right, shakes hands with manager Leo Durocher of the Brooklyn Dodgers at spring training in Havana, Cuba in March 1947. (SABR-RUCKER ARCHIVE)

In reviewing the career of Jackie Robinson in hindsight, one advantage is that everything seems as if it was a certainty. Robinson was one of the great players in the history of the sport, an innovator who was soon dubbed “Ty Cobb in Technicolor.”1 His Dodgers were an annual contender for the pennant, and Robinson became a fixture on those teams.

The future of Robinson looking forward was far less certain. He played out his career under a bevy of managers, and his interactions and appreciation (or lack thereof) for each is instructive as regards his personality and preferences in the days when the future of baseball’s “great experiment” was far from settled.

Unfortunately for the historians, Robinson apparently rarely had much to say about his earliest managers. He infamously hit .097 in his last (partial) season at UCLA and had played only a few months with the Kansas City Monarchs when Branch Rickey signed him for Brooklyn. Likely, Jackie Robinson’s determinedly negative view of the Negro Leagues impacted any potential lessons he may have drawn in his few months with the Monarchs.2

On the other hand, the pairing of Robinson and Montreal manager Clay Hopper in 1946 was an auspicious one. Robinson would write years later that he “had been briefed about Hopper. What I had heard about him wasn’t encouraging. A native of Mississippi, he owned a plantation there, and I had been told he was anti-black.”3 Hopper’s heritage was an open fact, and his reluctance to be the manager of an African American player was virtually certain. When he asked Dodgers GM Branch Rickey not to make him manage Robinson, the Mahatma supposedly offered, “You can manage correctly or be unemployed.”4

The legendary story about Hopper, as recounted by Rickey and subsequently by Robinson is that Rickey and Hopper were watching spring training together when Rickey praised a play by Robinson as “superhuman.” Hopper then asked Rickey, “Do you really think a n—-r’s a human being?” For his part, Rickey later explained, “I saw that this Mississippi-born man was sincere, that he meant what he said; that his attitude of regarding the Negro as subhuman was part of his heritage; that here was a man who had practically nursed race prejudice at his mother’s breast. So I decided to ignore the question.”5

Robinson’s season in Montreal provided all the evidence that Hopper needed as to his humanity and, indeed, near super-humanity. Robinson recounted himself that at the end of the season, Hopper approached him, offered a handshake, and exclaimed, “You’re a great ballplayer and a fine gentleman. It’s been wonderful having you on the team.”6 On another occasion, Robinson wrote of Hopper approaching him in September 1946 and telling him, “I’d sure like to have you back on the Royals next spring.”7 But of course Robinson’s 1947 season would be spent in Brooklyn.

The initial plan was for the legendary Leo Durocher to manager Robinson. Durocher had managed the Dodgers since 1939, and there was no reason to expect that he wouldn’t manage Brooklyn in 1947. During spring training Durocher himself went to work on changing the chemistry of the Dodgers clubhouse. Hearing rumors of a potential petition against Robinson making the Dodgers team, Durocher called a meeting of the rest of the team and advised, “I don’t care if the guy is yellow or black, or if he has stripes like a [expletive] zebra. I’m the manager of this team, and I say he plays.”8 Durocher also offered to make sure of the trade of any players who disagreed.9 However, a few weeks later, it would be Durocher and not Robinson who would be on the sidelines.

Durocher was suspended just before the season by Commissioner Happy Chandler for “conduct detrimental to baseball,” much of it likely centering on ties to organized gambling.10 The move so confounded Rickey and the Dodgers that Robinson’s first big-league manager was longtime coach Clyde Sukeforth, who skippered the first two games of the 1947 season. Sukeforth would later recall, “I remember writing out the lineup card, didn’t think anything special of it. I just wanted to follow what Mr. Rickey and Durocher wanted.”11

Sukeforth’s interaction with Robinson was much more significant than his two games as a manager. As the scout who brought Robinson into contact with Rickey, he was one of the first principal characters in the “great experiment.” He also helped Robinson greatly as a coach, to the extent that Robinson named Sukeforth as the person who had helped him most during his career in a publicity questionnaire that Robinson completed for the National League before the 1948 season.12

For his part, Sukeforth always professed surprise that Robinson gave him significant credit for his improvement as a player. Shortly before Robinson’s death in 1972, the two met at an event honoring Robinson at Mama Leone’s restaurant in New York. Sukeforth was called upon to speak and he downplayed his role in Robinson’s rise, only for Robinson to follow up a few days later by writing him, noting, “While there has not been enough said of your significant contribution in the Rickey-Robinson experiment, I consider your role, next to Mr. Rickey’s and my wife’s – yes, bigger than any other persons with whom I came in contact.”13

After Sukeforth’s two-game interim stint, veteran manger Burt Shotton took over as the Dodgers skipper. Shotton had last managed a major-league team in 1934, and his grandfatherly approach earned him the semi-mocking sobriquet of “Kindly Old Burt Shotton.” Along with Connie Mack, Shotton was one of the last two managers to wear street clothes rather than a uniform. His unassuming style was immediately impressed on the 1947 Dodgers, as he met with the team shortly before his first game and told them, “You fellas can win the pennant in spite of me. Don’t be afraid of me as a manager. I cannot possibly hurt you.”14

When his star rookie hit a lengthy early slump, Shotton simply continued putting Robinson’s name on the lineup card. Years later, Robinson wrote of Shotton, “He gave me all the opportunities possible. … When I broke in I had a particularly bad streak, but he handled me so wisely that I didn’t lose heart.”15 One biographer wrote of Shotton that he “was never given to extreme highs or lows. He kept a balanced perspective, which unfortunately was at times misinterpreted by reporters and fans as aloofness.”16

Shotton led the Dodgers through 1947, and returned to the helm in mid-1948, leading the team in a second run through the end of the 1950 season. The Saturday Evening Post noted, “[Robinson’s] rise to big-league stardom has come almost entirely under the managership of wise old Burt Shotton. This may be a coincidence, but seasoned students of the game do not think so. In their opinion, Shotton did a better job than Durocher or almost anyone else could have done in bringing Robinson through the dangerous period when he was the only Negro player in the major leagues.”17

For his part, Robinson later noted that Shotton “was quick” and his only issue with the older skipper was that “he almost never came out of the dugout.”18 In fact, because he didn’t wear a uniform, Shotton couldn’t come out of the dugout. The major-league rules prohibited him from doing so. But Robinson’s preference for a manager who would “[go] out on the field to fight the team’s battles”19 would require another protagonist.

In between Shotton’s two stints in Brooklyn, Robinson finally got a chance to play for Durocher, who returned from his suspension for the 1948 season, only to find Robinson wildly out of shape in spring training. When Durocher saw Robinson’s condition, he exploded, “What in the world happened to you? You look like an old woman. Look at all that fat around your midsection. Why, you can’t even bend over!”20 Durocher soon promised the media, “Robinson will shag flies until his tongue hangs out.”21

Durocher lasted only until the All-Star break, when he left the 35-37 Dodgers to jump to the archrival Giants. Robinson had rounded into shape and was hitting .295 at the time of Durocher’s departure. Still, from that point on, Robinson and Durocher were rivals. Durocher would bench-jockey Robinson, and the player would respond by alleging that Durocher wore his wife Laraine Day’s perfume.22 Day herself joined the feud, penning a letter insisting that Alvin Dark was a better second baseman than Robinson.23

For his part, Robinson didn’t seem to hold a grudge. He ranked Durocher his second favorite manager to play under, stating, “[I]f you have a winning team nobody is better than Durocher. … But with a losing team, Durocher would lose his composure.”24

On the other hand, Charlie Dressen was Robinson’s favorite manager. “Dressen was steady day in and day out, win or lose,” wrote Robinson.25 Dressen took over after Shotton’s second turn, and managed the Dodgers from 1951 to 1953. In his three seasons, Dressen led the Dodgers to a playoff for the NL pennant in 1951 and then back-to-back pennants in the following two seasons.

Dressen was not necessarily an easy manager to play under. Bill James wrote, “Dressen just couldn’t resist telling you, pretty much on a daily basis, how smart he was. Walker Cooper once said that Charlie Dressen wrote a book on managing; on every page it just said, ‘I.’ … Charlie was one of the few managers in baseball history who truly believed that he was the key to his team’s success.”26 James’s comments aside, Dressen knew who made the Dodgers go. During spring training, he told the media, “I am counting on Robinson to be the most valuable player in the National League next year.”27

Robinson delivered frequently during Dressen’s three seasons, and he held the skipper in highest regard. He wrote, “During the years I knew him as manager we players gave him one hundred percent effort. … He is the ball player’s best friend because he fights for the player’s rights.”28

Fighting for his rights was often on Robinson’s mind during Dressen’s tenure. Whether because he was no longer under Rickey’s request for restrained behavior or simply because he had become a veteran star in baseball, Robinson was often in the thick of the fray with umpires,29 and Dressen’s presence with him in those battles apparently weighed heavily in Robinson’s regard.

When Dressen couldn’t beat the Yankees in the 1952 or 1953 World Series and then wouldn’t sign another one-year contract with the Dodgers, the team moved on to Walter Alston. By this point, Robinson was on the back side of his big-league career, shuffling between multiple positions and seeing decline in his production. He frankly did not care for Alston.

Interestingly, in his own Baseball Has Done It, Robinson discusses his first three major-league managers (Shotton, Durocher, Dressen), and then pointedly does not discuss Alston in any way. A few years earlier in Wait Till Next Year, Robinson had spoken his piece. He wrote about an incident at Wrigley Field in 1954 when a call went against Duke Snider on a long drive that went over the wall but was erroneously ruled a double by umpire Bill Stewart. Robinson charged onto the field in protest of the call. His manager did not. Robinson later wrote, “Alston stood at third base, hands on hips, staring at me as if to say: All right, Robinson, all the fans see you. Cut out the grandstand tactics and retire to the dugout.”30

Once in the dugout, Robinson continued to express his feelings. “If that guy didn’t stand out there at third base like a damned wooden Indian,” he said in regard to Alston, “you know, this club might go somewhere. … What the hell kind of manager is that?”31

This wasn’t their first conflict, although it was the most public. Robinson recalled Alston approaching him soon after being hired, with hopes that Robinson would “put out for him the way I had for Charlie Dressen.” Nonplussed by the request, Robinson later noted, “I wondered why Alston should have any doubt about my putting out for him. … Yet I soon found out that Alston could not get over the notion that, because of my high regard for Dressen, I had to resent him.”32

An uneasy truce persisted between Robinson and Alston, and Robinson played out the last three years of his career, including winning the 1955 World Series. Alston stayed with the Dodgers much longer than Robinson and won three more World Series titles in Los Angeles. Alston made the transition from a playing career that included one big-league at-bat to winning 2,040 games as a manager and earning a spot in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Meanwhile, once Robinson retired, many wondered if he would ever manage. But even in 1964, Robinson wrote, “I used to have managerial ambitions. I don’t now.”33 He did go on to note, “Americans must learn … that many Negroes are qualified through experience for managing.”34

At Robinson’s final public appearance, for the 1972 World Series, mere weeks before his death, he told the crowd, “I am extremely proud and pleased to be here this afternoon, but must admit I’m gonna be tremendously more pleased and more proud when I look at that third base coaching line one day and see a black face managing in baseball.”35 In his final appearance, Robinson was again being a trailblazer and while he didn’t live to see Frank Robinson earn that honor or Cito Gaston become the first African American manager to win a World Series, he helped to jump-start those journeys.

JOE COX has written or contributed to 10 sports books. His most recent solo offering, A Fine Team Man: Jackie Robinson and the Lives He Touched, was published by Lyons Press in 2019. Joe practices law and lives near Bowling Green, Kentucky, where he’s looking forward to being able to return to rooting on the Class-A Bowling Green Hot Rods.

Notes

1 Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), 185.

2 An example of Robinson’s issues with the Negro Leagues can be found at Rampersad, 116.

3 Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made (New York: HarperCollins, 1995), 42.

4 Red Barber and Robert Creamer, Rhubarb in the Catbird Seat (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997), 274.

5 The entire incident is chronicled at Robinson, 48, but also at many other sources.

6 Robinson, 52.

7 Jackie Robinson, Baseball Has Done It (Brooklyn: IG Publishing, 2005), 54.

8 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 170.

9 Tygiel, 170.

10 Rampersad, 166.

11 C.E. Lincoln: “A Conversation with Clyde Sukeforth,” Baseball Research Journal, 16 (1987): 73.

12 The questionnaire is included in the Jackie Robinson Papers at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

13 Joe Cox, A Fine Team Man: Jackie Robinson and the Lives He Touched (Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons Press, 2019), 131. The original copy of Robinson’s letter is in the Jackie Robinson Papers at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

14 Peter Golenbock, Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1984), 169.

15 Robinson, Baseball Has Done It, 77.

16 David Gough, Burt Shotton, Dodgers Manager: A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1994), 58.

17 Roger Butterfield, “Brooklyn’s Gentleman Bum,” Saturday Evening Post, August 20, 1949.

18 Carl T. Rowan with Jackie Robinson, Wait Till Next Year: The Story of Jackie Robinson (New York: Random House, 1960), 264.

19 Rowan with Robinson, 264.

20 Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009), 448.

21 Lowenfish, 448.

22 Rampersad, 236.

23 The note was included in the New York Daily News, June 19, 1950.

24 Rowan with Robinson, 263.

25 Rowan with Robinson, 263.

26 Bill James, The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers From 1870 to Today (New York: Scribner, 1997), 187.

27 Rampersad, 233.

28 Robinson, Baseball Has Done It, 78.

29 Rampersad, 246 and 249 includes details of two such umpire feuds for Robinson.

30 Rowan with Robinson, 265.

31 Rowan with Robinson, 266.

32 Rowan with Robinson, 262-63.

33 Robinson, Baseball Has Done It, 78.

34 Robinson, Baseball Has Done It, 78.

35 A transcript of Robinson’s comments is included in the Jackie Robinson papers at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.