Mantle vs. Mays

This article was written by David Kaiser

This article was published in Willie Mays: Five Tools (2023)

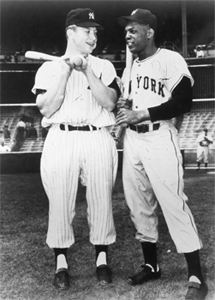

For decades, baseball fans have debated who was the better center fielder, Mickey Mantle or Willie Mays. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle were both born in 1931 and reached the majors almost simultaneously in 1951, competing against each other as rookies in the World Series. Together with Duke Snider, they appeared in 11 World Series between 1951 and 1956, and arguments about their relative ability raged throughout the city of New York and beyond. The older Snider faded from the National League’s leaderboards after that, but Mantle and Mays continued to dominate their leagues and start every All-Star Game in center field well into the 1960s. Until Henry Aaron’s successful pursuit of Babe Ruth’s all-time home-run record captured the nation’s imagination, they remained unquestionably the most famous and the highest-praised players of their generation.

Who was better – and in particular, who was the better player at his peak? In his first Historical Baseball Abstract in 1988, Bill James, the founder of modern sabermetrics, argued very strongly for Mantle. “Mickey Mantle was, at his peak in 1956-57 and again in 1961-62, clearly a greater player than Willie Mays – and it is not a close or difficult decision,” James wrote. Identifying Mantle’s three best seasons as 1957, 1958, and 1961, and Mays’ as 1954, 1955, and 1958, he used his runs created formula to measure offensive performance, and claimed that Mantle had created about 35 more runs per season in his best years than Mays had in his.

Turning to baserunning, which was not part of the runs created formula, James pointed out that Mickey’s stolen-base percentage (although not his stolen-base total) was higher than Willie’s, and that he grounded into far fewer double plays (obviously because he batted left-handed for the great majority of his at-bats). Then, without using any statistical method, James argued that while Mays was probably the greater center fielder, Mantle was “a very good center fielder,” and that the difference between them in the field could not possibly make up for Mantle’s superiority at the plate.1 By the time he brought out a revised edition of the Abstract in 2001, James had developed Win Shares, his single measurement of a player’s offensive and defensive value. Based on win shares, he now identified Mantle’s best seasons as 1957-58 and 1961 and Mays’ best as 1965. He did not assert Mantle’s superiority so dramatically, but he still claimed that those three seasons of Mantle’s were all better than Mays’ 1965 season.2 He also acknowledged that Mays had been by far the better player over the course of their entire careers.

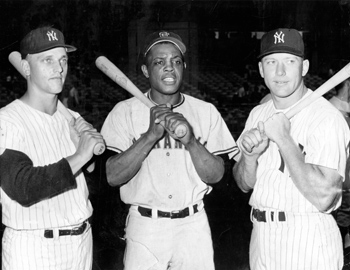

Roger Maris, Willie Mays, and Mickey Mantle gave fits to big-league pitchers. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

In 2011 Michael Humphreys published Wizardry, a new study of fielding statistics, which longtime sabermetrician Richard Cramer has described as “the greatest single intellectual accomplishment in the history of sabermetrics.”3 Humphreys used a new method, Defensive Regression Analysis or DRA, to measure the fielding ability of a player at any position against the league average at that position. By his measurements, Humphreys ranked Mays as the second-best defensive center fielder of all time (between Andruw Jones, first, and Tris Speaker, third), and wrote that Mantle’s defensive performance was only significantly above average in two of his 14 seasons in center field –1952 and 1959 – and was -41 runs worse than average over his whole career.4 Those numbers led me to reevaluate the question of whether Mantle’s best seasons really were significantly better than Mays’ based on the method I developed for my own book, Baseball Greatness.5

That method combines offensive data from the website baseball-reference.com with Humphreys’ fielding data to compute a single number for Wins Above Average. As I explained in this book, I used Wins Above Average (WAA) rather than Wins Above Replacement (WAR) because average performance can be computed much more accurately than replacement performance, and because WAA gives a much clearer indication of a player’s value to his team.6 I eventually defined a superstar season as 4 WAA or more and found 1,803 such player-seasons in the major leagues from 1901 through 2019. We shall see in a moment that Mays’ and Mantle’s best seasons were more than twice as good as that.

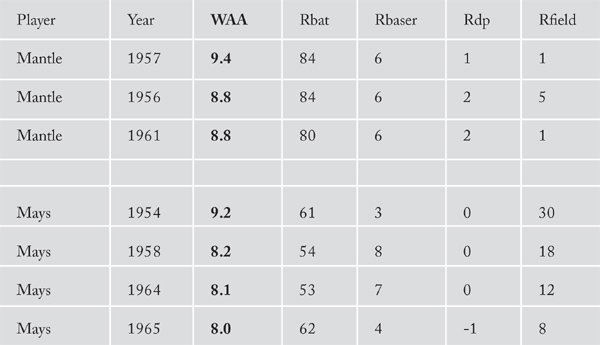

My calculations showed that Mantle’s best seasons (in order of highest WAA) were 1957, 1956, and 1961, while Mays had four seasons at a comparable level, 1954, 1958, 1964, and 1965. Rbat represents runs above average generated by hitting, Rbaser is baserunning runs, Rdp represents runs gained or lost via frequency of grounding into double plays, and Rfield is runs saved in the field according to DRA.

Before going any further, we must understand exactly how extraordinary these seasons were. Each man had one season with more than 9 WAA – and in the whole history of baseball there have been only 39 seasons that good. They also had five of the 59 seasons between 8.0 and 8.9 WAA. This table confirms that Mantle’s best offensive seasons were indeed superior to Mays’, mainly because Mantle walked so much more frequently. His batting runs above average (Rbat) substantially exceed Mays’ in every one of these years. In addition, Mantle was indeed very marginally superior as a baserunner because he grounded into fewer double plays, although Willie earned an extra run or two on the bases in other ways. Above all, however, Humphreys’ fielding data shows that Mantle, in two of these three seasons, was essentially average, while Mays ranged from significantly above average to the fielding stratosphere in 1954. And that is why, in place of the substantial overall superiority that James ascribed to Mantle, we find that he had only a marginal superiority comparing their best three seasons, and that only Mantle’s best season was superior to Mays’ best, which turns out to be 1954 because of his fielding. Mantle’s superiority in peak value earned the Yankees less than one extra win per season.

We must also look at one other adjustment. WAA measures an individual’s performance against league average performance, and by the mid-1960s the National League was significantly stronger than the American League because it was more integrated and included far more outstanding Black players. Comparing Willie’s and Mickey’s best seasons, we find that Black players earned only 60 WAA in the 1957 American League, while earning 143 WAA in the 1954 National League. Black players in the AL in 1956 and 1961 – Mickey’s two other best seasons – earned 99 and 138 WAA, whereas in the NL in 1958, 1964, and 1965 – Willie’s other greatest seasons – they earned 251, 560, and 645 WAA. Using a rough calculation, I attempted to estimate how much the additional Black players in the National League added to league average performance by “replacing” them, theoretically, with average players. The results of the adjustment are shown below.

| Player | Year | WAA |

| Mantle | 1957 | 9.4 |

| Mantle | 1956 | 8.8 |

| Mantle | 1961 | 8.8 |

| Mays | 1954 | 9.3 |

| Mays | 1958 | 8.4 |

| Mays | 1964 | 8.6 |

| Mays | 1965 | 8.7 |

Yankee fans, take heart. Mantle’s three best seasons are still superior to Willie’s – by the microscopic total of 0.1 WAA, equivalent to about one run created per season. While Mantle’s offensive contribution was bigger, Mays balanced that out with his almost unparalleled work in center field. Meanwhile, their joint dominance of their leagues for a 13-year period was extraordinary. Mantle led all American League hitters (and usually all AL players) in WAA six times: in 1955, 1956, 1957, 1959, 1961, and 1962. Mays led all NL hitters (and usually all NL players) 10 times, in 1954-58, 1960 (when he tied with Henry Aaron), 1962, and 1964-66. While Mantle won three MVP Awards and Mays two, both of them arguably deserved a lot more. And at their peaks they performed at an extraordinarily similar level.

DAVID KAISER first experienced Willie Mays on television during the 1954 World Series, at the age of 7, when he saw Willie’s famous catch in the first game. A historian, he taught for 37 years at Harvard, Carnegie Mellon, the Naval War College, and Williams College. He is the author of two baseball books, Epic Season, the 1948 American League Pennant Race, and Baseball Greatness: The Best Players and Teams According to Wins Above Average. He has given numerous presentations at local SABR chapters and at a number of national conventions. He lives with his wife, Patti Cassidy, in Watertown, Massachusetts.

NOTES

1 Bill James, The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Villard Books, 1988), 403-406.

2 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 728. James has never explained exactly how he incorporated fielding measurements into Win Shares.

3 Richard D. Cramer, When Big Data Was Small (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019), 54.

4 Michael Humphreys, Wizardry (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 286, 308-13.

5 David Kaiser, Baseball Greatness: The Best Players and Teams According to Wins Above Average (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2017).

6 I also dropped baseball-reference.com’s practice of adding points for players at more demanding defensive positions and taking points away from those at easier positions, for reasons that I explained therein.