Manzanar: Family, Friends, and Desert Diamonds Behind Barbed Wire

This article was written by Kerry Yo Nakagawa

This article was published in The National Pastime: Endless Seasons: Baseball in Southern California (2011)

“There was always the wind.” — Dennis Tojo Bambauer, orphaned internee living in the Manzanar Children’s Village

EFT Storytellers on Manzanar Baseball Field. Left to right: Kerry Yo Nakagawa, Nisei Baseball Research Project; Pete Mitsui, founder of San Fernando Aces; Jeff Arnett, former director of education at the National Baseball Hall of Fame. (Courtesy of Nisei Baseball Research Project)

Growing up in the small farm town of Fowler, California, we used to travel east towards the Sierra Nevada mountains to go fishing or picnic at the river or lakes. I remember hearing stories about camp life on the “other side” of those mountains—at Manzanar—from my cousins. My relatives and community lived in the animal stalls of the Santa Anita Race Track because of President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. Six months later, they transferred to the permanent Manzanar Detention Camp between the towns of Lone Pine and Independence, in California’s Owens Valley over the mountains from where we [later] fished.

My cousin, Aiko Harada, was one of 10,046 inmates/internees and had her first child at Manzanar. “We had to stuff our mattresses with hay and shared our tiny space with my husband’s parents. The only privacy we had was the blanket hung between us,” Aiko said.

My relatives were a small part of the 120,000 West Coast persons of Japanese American ancestry who were removed from their homes in 1942, neighborhood by neighborhood. The temporary Assembly centers were built throughout California at racetracks, fairgrounds, and similar facilities. Detainees spent much of the spring and summer of 1942 in these facilities. Conditions were generally poor, as might be expected given the haste in which they were built. Residents complained of overcrowding, shoddy construction, communal showers, and toilets with no partitions. The worst indignity was being housed in the odorous horse stables or animal stalls at the race tracks of Santa Anita, Tanforan (near San Francisco), and Fresno. Military police patrolled the perimeters and regulated visitors. Internal police held roll calls and enforced curfews. Inside the animal stalls of the assembly centers, families reflected on their lost homes, educational opportunities, businesses, cars, furniture, and heirloom artifacts, which had been sold for ten cents on the dollar. They had been able to bring only what they could carry in two suitcases. One of the first problems facing the internees was to establish a sense of routine in the face of totally disrupted patterns of life. Cultural, recreational, and work activities took on tremendous importance. There were schools for the children and many adults were government employees earning standard G.I. wages. Doctors and other professionals earned the top $19 monthly wage. Teachers, secretaries, and other support staff earned a $16 monthly wage, and laborers were paid $12 per month.

Through the hardships of the searing summers and harsh winters, Japanese Americans and baseball began to flourish. Although the government took away constitutional rights, freedom, radios, cameras, religion, and for the immigrant Issei, their native language, Uncle Sam did not deny Japanese Americans the right to play the All-American Pastime of baseball. George Omachi, a former Nisei (first generation born in the US) baseball player, manager and Houston Astros scout said, “Without baseball, camp life would have been miserable…. It was humiliating, demeaning, being incarcerated by our own country.” Assembly center baseball teams began to organize and develop almost immediately. Baseball played a major role in an effort to create a degree of continuity and recreation. Playing, watching, and supporting baseball inside America’s concentration camps brought a sense of normalcy to then very abnormal lives, creating a social and positive atmosphere for the internees. Arts and sports practiced by the internees were not entertainment but approaches for finding, articulating, and preserving meaning in a senseless situation. Former internee Pete Mitsui, founder of the San Fernando Aces and coach of the Manzanar camp champions, said, “The ballclub was an important part of the community identity.

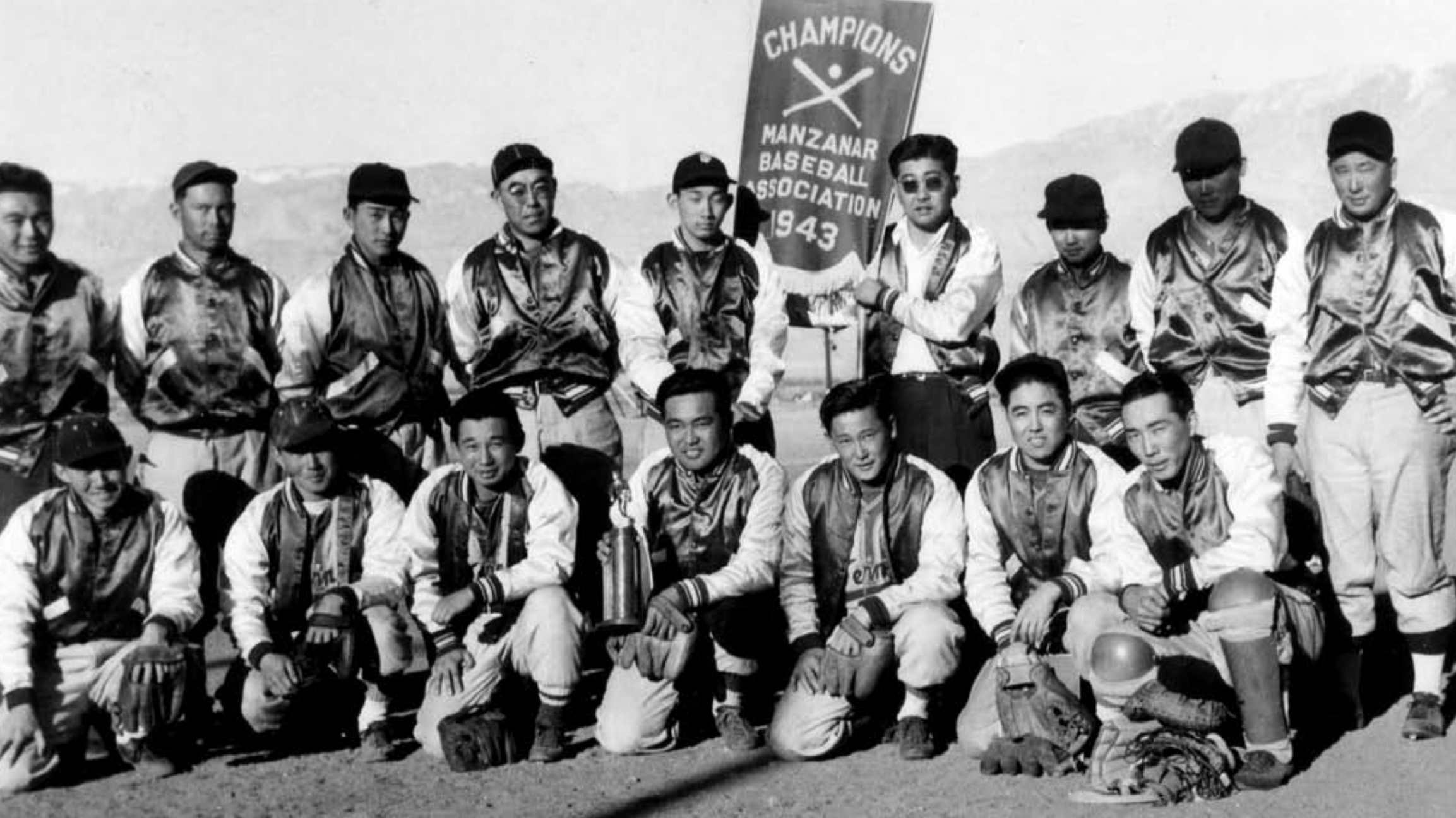

Manzanar Champions. The prewar San Fernando Aces team were the camp champions. Top row, fourth from left: Founder of the Aces Pete Mitsui. (Courtesy of Pete Mitsui)

Examining that history today is a way to explain not only what happened but why the internment camps episode occurred, as well as how the 1942 events connect to today’s issues.

All ten permanent camps in the US built diamonds and established teams and leagues. At Manzanar, the teams took turns driving a dump truck to the hills for decomposed granite. They would lay granite down in the bleacher and dugout sections of the ball field, as well as the infield to cut down on the dust that stirred up during the games. San Francisco Aces catcher Barry Tamura worked for the camp fire department and ensured the field was watered down by conducting frequent fire drills on the diamond. At Manzanar’s “A” Field, thousands of fans gathered to watch their hometown heroes from the San Fernando Aces, San Pedro Skippers, Scorpions, Padres, Manza Knights, Oliver’s, Has-beens and other organized teams of the camp’s twelve leagues. The Aces and Skippers were prewar, semipro powerhouse teams coming into the camp established, while other teams formed in the camps. By the summer of 1942, the camp newspaper, The Manzanar Press, was covering nearly 100 men’s and 14 women’s softball teams like the Dusty Chicks, Modernaires, Stardusters, and Montebello Gophers. The four primary “A” teams who were considered semipro were the Guadalupe YMBA in Gila River, Arizona, the Florin AC at Jerome, Arkansas, the San Fernando Aces at Manzanar, and the Wakabas at Tule Lake, California. “If it wasn’t for the war, I think we could have had a Japanese American major leaguer even before Jackie Robinson,” said Tets Furukawa, a pitcher for the Gila River Eagles.

Rosie Kakaucchi played on that field with the Dusty Chicks and was an all-star catcher. “We were so good we even challenged the men to play us and we beat them,” she said. Rosie’s husband Jack would enlist and play third base for Camp Grant, an Illinois Army team. In 1943, the Camp Grant team would beat the Chicago Cubs in an exhibition, 4–3.

Baseball serves as a touchstone to compare and contrast different cultures, since Japanese Americans in the internment camps had white teachers who reinforced mainstream values. No matter how remote, how desolate the camps were, baseball was a vehicle to give focus to lives and link the prisoners to their culture and their community. Baseball serves as a lens to examine camp history and provide an opportunity for people to discuss the delicate and troublesome stories of internment. Baseball provides the common grounds with which these people can identify with all diverse cultures. American citizens of the Issei and Nisei generations were imprisoned by their own government primarily because they looked like the enemy, while German and Italian Americans were not. As a result, internment camps are central to Japanese American culture. Japanese American baseball is a story of inclusion within the context of exclusion. Against their backdrop of exclusionary laws, baseball was passionately played within the community by local teams. In the beginning, internment camp conditions were dismal and morale was low. The adults sought out baseball as a way to bring a sense of normalcy to the futility of daily life. Baseball not only created a positive atmosphere, but encouraged physical conditioning, and maintained self-esteem despite the harsh conditions of desert life and unconstitutional incarceration.

The irony of baseball behind barbed wire was that Japanese Americans were considered enemy aliens and confined to camps. Donning a baseball uniform, however, gave them free passage to road trips from Gila River, Arizona to Heart Mountain, Wyoming or Amache, Colorado. “The ball players would usually travel in small groups of five or six so that we would not create attention,” said Howard Zenimura. “None of the citizens of the different towns and cities we passed through paid us much attention.” The players would travel by Greyhound bus hundreds of miles for a one- or two-week road trip. The other irony is that most of the diamonds were built outside of the barbed wire. Sab Yamada, an outfielder with the Fresno Assembly Center team, said, “Where would you run to? There were hundreds of miles of desert and most of the government officials were upset that they were in the desert too…[T]here was no treachery or espionage going on in the camps.”

Famed prewar photographer Toyo Miyatake took this photo from center field looking into the grandstands of Manzanar. He smuggled his lenses into camp, building boxes around them to make homemade cameras, and took over 40,000 images. (Courtesy of Toyo Miyatake Studios)

On February 13, 2007, the Nisei Baseball Research Project joined the National Park Service, Ball State University, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame for an “electronic field trip” (where classrooms all over the country are taken to an interesting place via a television satellite hookup). A group of students from Kansas schools won the contest to host the show.

Through the prism of Manzanar, students learned about Japanese American internment. Secretary of the Interior Dirk Kempthorne, with Nisei veterans Joe Ichiuji (liberated Dachau with the highly decorated all-Nisei 442nd Regiment Combat Team) and Grant Hirabayashi (Army Ranger Hall of Fame) helped facilitate questions.

We met that frigid morning to clear out sagebrush and tumbleweeds on the baseball fields of Manzanar. Pete Mitsui, manager and former player of the Manzanar champions, led us to where the bases used to be. At first base, we discovered a rusty peg that had anchored the base back in 1942.

“Seeing our kids so excited and getting the opportunity to host a live show was the highlight of my educational career,” said Dan Brown, a teacher from Kansas. For Tom Leatherman (former superintendent of Manzanar), it was all about the kids telling the story of internment. “Watching the students become the voice and engage and share their discoveries with millions of other kids across the country was powerful.”

I personally will treasure looking at the towering slopes of the Sierra Nevada mountains, being part of this historic event with my peers and Nisei “Pioneers” and playing catch with Tom Leatherman after clearing, leveling, grooming, and lining the “new” Manzanar baseball field. Manzanar is a Spanish term meaning “apple orchard” and reminds us that the interned Japanese Americans were as American as mom, apple pie, and baseball. They kept the All-American Pastime alive, even from behind barbed wire. In their world, life brought a desert and they built these diamonds in the rough, persevered, and eventually made it home.

After 1945, most Japanese Americans had very little. Most came back to nothing, but they could still meet every Sunday at the ball field, forging community and fellowship. Through its positive identity and image, baseball helped salve the deep wounds of war.

Similarly, the story about baseball behind barbed wire contains the potential to transform not only Japanese-American communities, but American communities throughout the nation because of its heroic triumph over discrimination and xenophobia.

KERRY YO NAKAGAWA is founder of the non-profit Nisei Baseball Research Project (www.niseibaseball.com). He is founding curator of the “Diamonds in the Rough” exhibit that has been displayed at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame in Tokyo, and museums around the country. He was the associate producer and actor in the feature film American Pastime.

Sources

Nakagawa, Kerry Yo, Through A Diamond, 100 Years of Japanese American Baseball, (San Francisco; Rudi Publishing, 2001), Chapter Six.

Author Interviews

Kakauuchi, Rosie (2010), Mitsui, Pete (1997, 2010), Lynch, Alisa (2010), Leatherman, Tom (2010), Brown, Dan (2010), Zenimura, Kenso (1996, 1997, 2010), Yamada, Sab (1997), Omachi, George “Hats” (1996), Harada, Aiko (2010) Furukawa, Tets (2010).

For more information

- Manzanar National Historic Site. www.nps.gov/manz. (760) 878-2194 Manzanar is located on the west side of U.S. highway 395, 9 miles north of Lone Pine, California and 6 miles south of Independence, CA.

- Ball State University. www.bsu.edu. 2000 W. University Ave. Muncie, IN 47306. (800) 382-8540 and (765) 289-1241.

- National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. www.baseballhall.org. 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326-1300. (888) 425-5633.

- Nisei Baseball Research Project. www.niseibaseball.com.

- Toyo Miyatake Studios. 285 West Fairview Avenue, San Gabriel, CA 91776. (626) 289-5674.

- Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education. spice.stanford.edu. (650) 723-1116.

- American Pastime. Film. Warner Bros. (2007). www.warnervideo.com/AmericanPastime.

- The Asian-American jazz-fusion band Hiroshima has a song entitled “Manzanar” on its album The Bridge (2003). It is an instrumental song inspired by Manzanar and the Japanese American internment.