Mark Harris: ‘You’re A Fan’

This article was written by Mark Harris

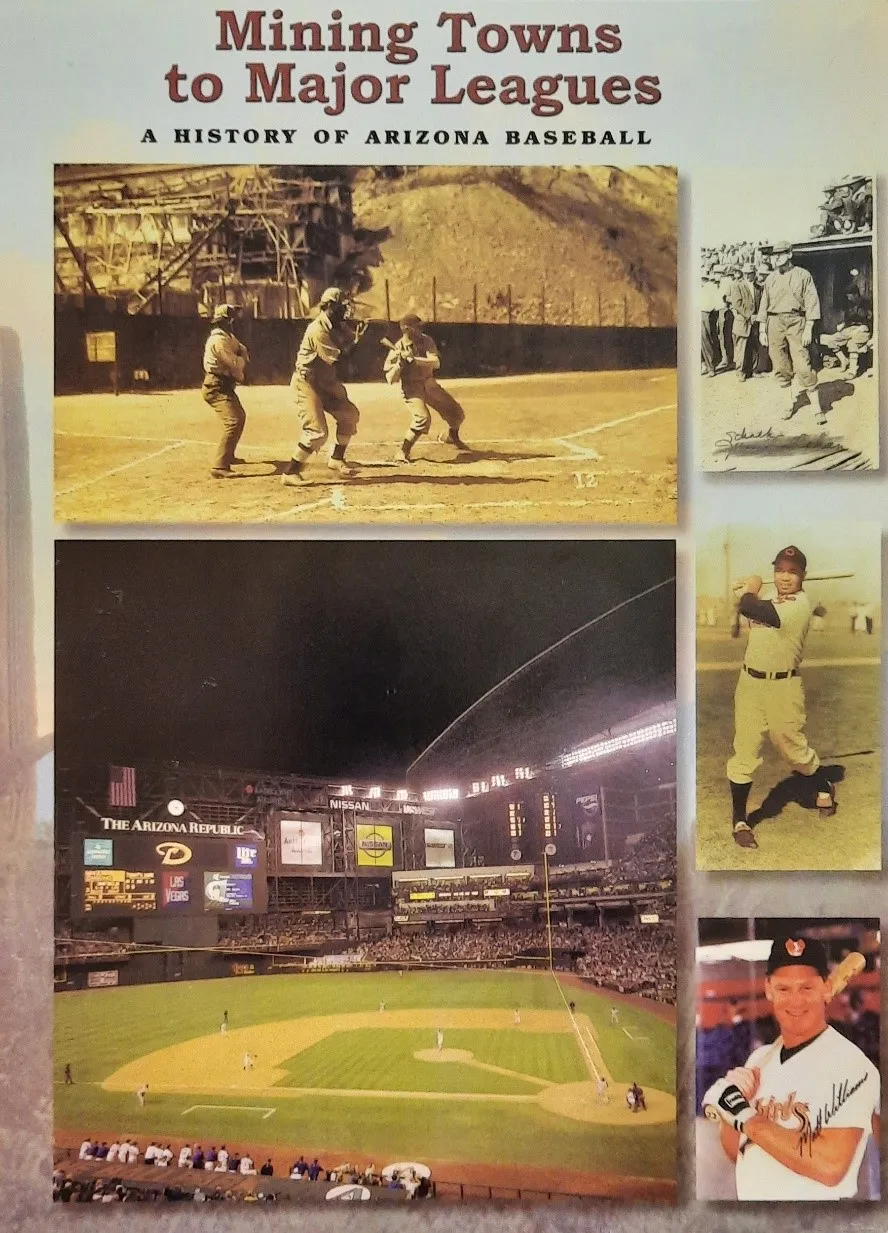

This article was published in Mining Towns to Major Leagues (SABR 29, 1999)

Before the Arizona Diamondbacks’ inaugural Opening Day on March 31, 1998, author Mark Harris, Arizona’s poet laureate of baseball, wrote this fanciful essay focusing on the undercurrent of resentment among many Arizona baseball fans and one fan’s struggle to accept the new ball club. A version of this story originally appeared in the Mesa Tribune on March 31, 1998. Reprinted with permission of the author.

Good old Jones claimed from the beginning that “the baseball thing,” as he called it, had been jammed through. The politicians had been bought and the public had been deceived. Jones had neither forgiven the politicians nor ceased to yearn for the enlightenment of the defrauded masses.

Good old Jones claimed from the beginning that “the baseball thing,” as he called it, had been jammed through. The politicians had been bought and the public had been deceived. Jones had neither forgiven the politicians nor ceased to yearn for the enlightenment of the defrauded masses.

His friend Gussie told him there wasn’t any sense in fighting “the baseball thing.” “It’s going to be a good thing in every way,” Gussie said.

Jones replied, “We shouldn’t be selling out democracy for a baseball team.”

Early in 1998. Gussie tried to sell Jones a bargain share in a season ticket: twenty-five games, twenty-five bucks a game. Jones declined to buy. “The trouble with you,” Gussie said, “you’re not a fan anymore. You don’t go to games.”

“Certainly I go to games. I go to high school games and I go to college games and I go down the street from my house and watch the great softball games the 16-year-old women play on two beautiful ballfields there.”

“That’s not baseball, that’s girls. Nobody goes to those games.”

“I’m not nobody and I go, and the mothers of the players go, and the fathers go when they can.”

“Well, you’re just not a fan.”

Big-league baseball was on the way to Phoenix, requiring only a stadium to play in. Phoenix had many fine ball parks everywhere, but none could accommodate big-league crowds—fifty thousand baseball-hungry, baseball-mad, fervent, ardent, screaming, passionate, hollering crowds smashing down the gates from April to October, cheering on those Diamondbacks (as they were soon named) to victory and fame, proving to the world that Phoenix was a big-league city. Jones said, “Are we really going to allow an immense nuisance of an ugly ball park right here in beautiful downtown Phoenix?”

“It’s going to be a beautiful baseball park,” Gussie said.

“I never saw a beautiful baseball park,” Jones replied. “Ball parks are by definition cement and steel.”

“The grass is always beautiful,” said Jones’s friend.

“Grow the grass,” said Jones, “bury the steel and cement.”

Some of Jones’s friends were becoming his enemies.

After a passage of time the structure was built. It gave lots of people work. It was named for a bank. A former friend said to Jones, “Now that it’s done I predict that you’re going to be there Opening Day, March 31, like everybody else,” and Jones replied, “No, I’ll make you my own prediction.” Fans love predictions. They want to know the future ahead of time.

“I’m predicting,” Jones said, “that I will not be there in the park named for a bank on Opening Day, March 31. You’re going to have to open the damn thing without me.”

His friend said, “I don’t understand you. You used to be a baseball fan.”

Jones had predicted accurately. On March 31, 1998, he was absent from Opening Day at Bank One Ballpark. Nor was he in attendance at any game at Bank One Ballpark during April 1998 or May 1998, or June or July or August of that year.

As for the Diamondbacks, in mid-April they led the league. April heroes arose whose names nobody had known in March. One day in April a Diamondbacks pitcher pitched a no-hit game, and on another day in the same month a Diamondbacks outfielder hit three home runs.

However, the Diamondbacks failed to keep pace. They dropped from first place to the second division, thus disappointing the fans who had from the outset forgiven them for the bought politicians and their tricky defrauding of the public.

In June 1998, the fans began to focus their attention on the features of the stadium they had ignored in their earlier period of optimistic forgiveness. They recited their discomforts. Ticket prices were too high. Parking was difficult or impossible. The lavatories were repulsive. Refreshments were too expensive and the waiting lines too long. (A friend of Jones said he missed an inning and a half on the hot-dog line. “Take a sandwich in your pocket,” said Jones. “It’s against the law,” his friend said.)

The fans began to boycott the Diamondbacks. There was nothing organized about this. No picket signs, no parading. It was invisible. The fans just stayed away from Bank One Ballpark. Rumors flourished that the Diamondbacks were about to move to Salt Lake City. Some people said they never should have come in the first place—Phoenix was already big-league enough. Didn’t Phoenix already have big-league teams in three sports? Who needed four?

One day in September, Gussie gave Jones a ticket. Jones had not yet attended a game in Bank One Ballpark. With a sandwich in his pocket he went on a Wednesday night and saw what he called “a good ball game.” For Jones almost any baseball game was “a good ball game.” He sat practically alone in the vast quiet of the ballpark. Gosh, there were only 8,000 people there. What had happened to the baseball-hungry, baseball-mad, fervent. ardent. screaming, passionate, hollering crowds? Parking was easy—the parking attendant seemed to have been called away. There was no delay in the refreshment line. The lavatory sparkled.

The Diamondbacks lost the game. They had played very well, and they would have won if only the other fellows hadn’t played better. After the final out of the game Jones stood and applauded.

He thought how fortunate the team was—it had nowhere to go but up. He felt he, too, was only beginning. He returned the next day with another sandwich in his pocket. The crowd dwindled to 5,000.

He rather liked this ball park. After all, no ball park had ever resembled Eden. It was only steel and cement like any other. Jones had known that this was how it would be. He gave himself credit for the instinct of his critical, cranky mind. He had kept cool. He had honored his memory of experience above mere hope. He had not expected miracles. He had been following baseball for many many years and he had never heard a single miracle.

He felt himself keenly alive in a big-league ball park. He felt himself also for a moment confident that fans who yearned to think of themselves as alive in a big-league city would surely feel and understand that they were going to have to live with a ball club under all circumstances. The Diamondbacks had begun at the bottom. There was nowhere to go but up. The fans would grow up with the team.

The Diamondbacks won. Jones applauded. Here came Gussie down the row. “Hey, Jones,” he said, “it’s another one-game winning streak. Did you ever seen such a small crowd? Where’s all the people?”

“I’m here,” Jones said.

“Well, you’re a fan,” said Gussie.

Mark Harris makes his home in Tempe, Arizona, where he is a professor of English at Arizona State University. He is best known for his baseball novels, including the contemporary classics Bang the Drum Slowly, The Southpaw, A Ticket for a Seamstitch and It Looked Like Forever.