Marvels or Menaces: How the Press Covered ‘The Lady Baseballists,’ 1865-1915

This article was written by Donna L. Halper

This article was published in Spring 2022 Baseball Research Journal

It wasn’t so long ago that sports historians spent little if any time researching the young women who played baseball in previous generations. The best-known histories of the game barely gave them a mention.1 This is not surprising, since the common wisdom about female ballplayers was that most of them weren’t very good at it, and those who tried were only motivated by the desire for some publicity. These women were usually thought of as entertainers rather than athletes.

One other reason so little research was done about women baseball players was the belief that baseball was a man’s game, and the women who tried to play it were seen as interlopers. Worse than that, they were seen as unfeminine. In the late 1800s, as baseball (then spelled “base ball”) grew in popularity, the men who reported for the newspapers and magazines regularly expressed the attitude that a baseball club was no place for a lady, nor did the “weaker sex” (as women were often called back then) possess the natural ability needed to play the game. As one reporter put it in 1875, “There are some things a woman can’t do! [T]here are a great many essential elements that go to make up a base ball player, and to the best of our knowledge, women check out short on all of them.”2 A similar viewpoint was articulated by Albert G. Spalding in his 1911 book, America’s National Game, in which he asserted that women were best suited for sitting in the stands and cheering for the home team. “[N]either our wives, our sisters, our daughters nor our sweethearts, may play Base Ball on the field… Base Ball is too strenuous for womankind,” he wrote.3 For Spalding and other men of his time, baseball was the epitome of a manly pursuit. It represented “American male vim, vigor, and virility.”4

Of course, in the late 1800s, teaching girls to play baseball (or any “masculine” sport) was considered a radical idea. But it was not the only radical idea being considered at that time: there was a contentious debate taking place about how much education girls needed. Many people believed that, since girls were destined to be wives and mothers, they did not require much more than a basic education, focused on homemaking skills; and there was certainly no need for them to go to college. But at a growing number of women’s colleges, instructors disagreed: they defended higher education by insisting their curriculum would turn young women into better wives and mothers, and that college would make them more effective when teaching their children. (And for unmarried women, teaching was one of the few permitted occupations, so why not provide them with the training needed to earn a living?) Meanwhile, some women’s colleges began offering students a chance to participate in athletics, as part of an effort to promote good health through exercise. But that too was contentious, since many people of that era, including numerous physicians, believed women’s bodies were designed mainly for childbearing and that too much exercise would harm the uterus, rendering the woman unable to conceive. Thus, playing sports was often discouraged.5

But at Vassar College, the administration was undeterred by these cultural debates. Young women were given the opportunity to play baseball beginning in 1866, and that first year, at least twenty-three collegians participated.6 (There were probably others who were curious, but who hesitated to try out, fearing the disapproval of their parents, or friends, or the society at large.) As time passed, there was always a small group of young women who wanted to play, but subsequent years proved more challenging when it came to keeping the club going. It had to disband several times, but it always came back, and from 1866 to 1876, it was usually able to find enough players.7

Eventually, the Vassar club disbanded for good, but other colleges, including Smith, had begun to field baseball teams. And during the 1870s, there was another phenomenon taking place: a few semi-pro female clubs were being formed. They traveled to various cities and played against local teams. Occasionally, the women played against men, but more often, they competed against other women—games featuring the “blondes versus the brunettes” were written about in the newspapers. The talent on these clubs varied, which was also true of the male semi-pro teams. But unlike the male teams, the female clubs were formed in a culture where girls were not taught baseball’s fundamentals from an early age, nor given the chance to practice and improve through organized team play. Thus, despite these limitations, the fact that some women managed to learn the game and travel to different cities to play it was noteworthy.

However, the media of that day often did not see these female clubs as noteworthy. Nor did they see the efforts of women who wanted to play baseball as commendable. Reflecting the cultural beliefs of their era, most sportswriters were either dismissive or scornful. Modern fans are accustomed to today’s young women successfully playing a wide range of sports (including Little League baseball), and they might find past attitudes disappointing; but for writers who covered sports in the era from the 1870s to the early 1910s, marginalizing women athletes made perfect sense. Back then, nearly all baseball writers were male, and like Albert Spalding, they tended to see baseball as something that only men did. Thus, as a media historian, I expected that reporters from the nineteenth century would either disapprove of women ballplayers or not take their efforts seriously. However, I wondered if any sportswriters wrote positively about women athletes, and I wanted to know if there were any common threads in the way the writers of that time reported about the women “baseballists.”

As I often do when performing historical research, I utilized a theoretical framework called content analysis; it provides a useful way to evaluate what reporters wrote. Content analysis “has a history of more than 50 years of use in communication, journalism, sociology, psychology, and business… [It is] the systematic, objective, quantitative analysis of message characteristics.”8 In other words, by categorizing and analyzing the articles that appeared in the newspapers of a given era, it becomes possible to determine which topics were most frequently covered by reporters, as well as which assertions about various trends in society were most often expressed. For this article, I explored a wide range of digitized sources, from more than fifty cities and towns, using three databases: Newspapers.com, Newspaperarchive.com, and Genealogybank.com. In addition, I explored a few books and magazines from the late 1800s and early 1900s. My research was also informed by some scholarly articles about nineteenth-and early-twentieth-century sex roles that I accessed on the JSTOR database. The goal was to get a thorough overview of what was written about women athletes in publications across the United States, since what appeared in print often reflected, and sometimes influenced, public perceptions.

My findings fell into four basic categories: writers who treated women ballplayers as a joke; writers who treated women ballplayers as an offense to traditional morality; writers who were dismissive of the efforts of women to play baseball; and writers who reported on women ballplayers positively (or at least tried to be fair to them). I also noted a fifth category—“star” athletes, specific women who received glowing coverage that other female players did not.

SPORTSWRITERS AS JOKESTERS

For most male reporters of the late 1800s, the thought of women trying to play men’s sports was laughable. After all, a female player couldn’t throw like a man, or hit like a man, or run the bases like a man, and yet, she thought she was a baseball player? How absurd! That may explain the number of jokes, quips, and snide remarks about women ballplayers that were printed (and reprinted) in newspapers across the United States. Most newspapers of the late 1800s did not have a sports section, and that meant articles about sports could appear on almost any page; and so could the quips and jokes. It was also very common for a story to be printed in one paper and then picked up by another newspaper’s Exchange Editor, whose job was to read newspapers from many cities and then select interesting stories that local readers might find worthwhile. That is how, in that era before radio, TV, and Internet, a story (or a joke) could start in one city and end up being read halfway across the country.

In the case of women baseball players, many of the attempts at humor revolved around common stereotypes: all a woman really wanted was a husband; women were vain and self-centered; women mainly cared about shopping for beautiful dresses; women were only happy in the kitchen. For example, you can find some kitchen humor in this joke in a piece about the Piqua (Ohio) female baseball club: “[The players] appear on the ball ground, each armed with a cook book, and think they know that to make a good batter, a little milk, a few eggs, a thingful of sugar, some salt, and so on, are all that are necessary. They have got their batter mixed, don’t you see.”9 A similar theme can be seen in this one, where the writer uses humor to remind readers of women’s “proper” place: “Detroit has a female base ball club. The [New York] World says, if we might suggest our preference, we should say that batter-pudding and milk-pitchers were more in women’s field.”10

Similarly, we find puns about a woman’s ability to “catch” a husband: “Some of the ladies of this place have organized a female Base Ball Club. The married members are said to be good ‘catchers’ and are instructing the unmarried…”11 (This attempt at humor is interesting, because it is one of the earlier mentions, even jokingly, that women are playing baseball—from 1867.) Another kind of joke involved the cultural belief that women did not get along with other women. This one, which also contains the implication that female players don’t take the game seriously, tells the possibly apocryphal story of two players from “the female base ball club in Cincinnati,” where two players got into a fight over a paper fan: “The left fielder went to her position with a fan in her hand. Her captain ordered her to put the fan down, but she persistently used it. The captain seized it, tore it into shreds, and was at once grappled by the angry left fielder. The encounter was short but vigorous.”12 (I believe that this, and some of the other jokes, may be apocryphal because the players who allegedly did the particular thing are never named, nor can I find any newspapers that give additional details about these incidents.)

One other interesting category of jokes focused on parental disapproval of young women playing ball. A frequently reprinted story tells of a female player who had a “home run” of sorts. “New Lisbon, Ohio has a female base ball club. One of the girls recently made a ‘home run.’ She saw her father coming with a switch.”13 In some versions of the story, it was the young woman’s brother or mother, but in all versions, it was understood that the family members had every right to force her to stop playing—whether she wanted to or not.

This story takes place in New Orleans (like New Lisbon, the Crescent City actually did have a female club), and while the game was going on, “…a young man darted out of the crowd, and seized one of the young women by the back of the neck” and “started to rush her off the field. ‘Police!’ shouted the manager, ‘Arrest that man!’” But the young man was undeterred. He calmly replied that the girl was his sister, and that he was going to take her home. The story concludes, “And he did.”14

But one snide comment that appeared in an 1886 newspaper best sums up the general attitude of many editors: “Chicago has a gang of riotous Anarchists, and New Orleans has a female base ball club. We pity New Orleans.”15

SPORTSWRITERS AS GUARDIANS OF MORALITY

Contemporary baseball scholars, including Leslie Heaphy, Debra Shattuck, and Jennifer Ring, have written about how women faced cultural and family disapproval for wanting to play baseball. But some of the reporters of the late 1800s and early 1900s objected to female baseball clubs because, in their view, these clubs violated public morality. To them, women who participated in “masculine” sports were a menace; by acting in such a vulgar and un-ladylike way, they set a bad example for other young women, who might imitate these indecent behaviors. As one outraged reporter wrote about the female club in Springfield, Illinois, “However people may differ on the influence of base ball on the rising generation, there is no room for doubt as to the impropriety of women engaging in it. By doing so, they forfeit the respect which is due to [their] sex, and which is all that gives its members a greater moral influence…”16

The day before, the same newspaper, and perhaps the same writer, had referred to the female baseball club from Springfield as a fraud, or in the parlance of that era, a “humbug,” and said that people should refuse to attend their games, so that the club would have to disband. In fairness, the writer said they were frauds because they “[did] not know how to catch, pitch, throw a ball, or run”17—which seems like somewhat of an exaggeration. And given the previous day’s editorial accusing the players of immorality, one wonders how objective the newspaper was in assessing their skills.

Numerous reporters of that period shared the belief that women who played sports were deserving of the public’s scorn. But few were more outraged than this writer (it is unfortunate that the custom back then was for most newspaper reporters to be anonymous; few received a byline, making it difficult for historians to know who wrote what), who referred to the female baseball club that played recently as, not just a fraud, but a “sickening and repulsive fraud,” and, just for emphasis, a “pernicious and putrid” fraud. And the writer also put a question-mark next to the word “lady” when describing the “young lady (?) baseballists.”18

Equally outraged, and equally certain that no decent woman would ever play baseball, a reporter for the Knoxville Sentinel demanded that the police forbid a traveling female club from playing in that city. These women were surely of “notorious character,” and “the worst of their class,” since women who played baseball were not fit to call themselves “ladies.” And the reason they were such vulgar human beings was obvious to the writer: “These ‘ladies’ are from New York, and New York is noted for its curious people and curious customs.”19

Said another reporter, female baseball clubs were a danger because they attracted “the filthiest elements of the city.” And when some in the crowd began to fight at one of the games, this reinforced the reporter’s belief that the women themselves were low-class. “…the exhibition of common women in the exercise of functions that are not womanly—no matter whether in the name of art or athletics—is both repugnant and dangerous to public decency.”20 It is worth noting that fights broke out at men’s games too, but somehow, anything that went wrong at a game where women were playing meant the women were to blame for it.

The recurring insistence by so many writers that women who played baseball were not “ladies,” may seem like a strange thing to say in 2022, but it was frequently expressed a century ago, when gendered roles were still much more rigid, and women who violated cultural norms were immediately accused of a lack of morals. This again reminds us that the young women who wanted to play had to be both determined and courageous, since they were constantly facing ridicule from the press, and regularly stereotyped as somewhat less than respectable.21

SPORTSWRITERS AS DISMISSIVE

It goes without saying that most female ballplayers of the late 1800s were still learning the game. Few had been allowed to play it as children, and by the time they started, their inexperience certainly showed. But all too often, reporters seemed unwilling to look beyond that inexperience and see potential. This should not have been difficult to do: lots of new players are nervous or awkward when first starting out, as anyone who has covered single-A minor league games can attest. And yet, many reporters seemed focused on pointing out all the flaws of the women players, rather than noting anything good they did. They also described in great detail how the players looked: “The pitcher was a lovely brunette, with eyes full of dead earnestness; the catcher and the batter were blondes, with faces aflame with expectation.”22 And the writers placed considerable attention on every detail of the players’ uniforms, while observing that most of the fans were there to enjoy looking at the young women, not because they expected an actual baseball game.

Few reporters expected an actual baseball game either. One summed up an early July 1879 game between the New York Red Stockings and the Philadelphia Blue Stockings by concluding, “The women worked very hard to gain fame as athletes, but failed miserably. They muffed terribly, and batted in a very weak manner, so much so as to satisfy the crowd that women will never become base ball players.”23 A reporter for a rival paper came away with the same conclusion about that game: “The match was a farce. Not the least base ball talent have the women. Every fly was muffed, and it was only by chance that a player was put out.” The writer also noted that the majority of the attendees were there due to the “novelty” of women playing baseball.24

Even the reporters who tried to be charitable towards the early female clubs found it puzzling that women would want to play baseball. One reporter wondered why young women would demean themselves and sacrifice their “womanly delicacy” by displaying their lack of talent in front of total strangers. The thought that their talent might improve over time was never considered; based on the numerous critical articles I read, few of the writers believed this was even a possibility. The writer of one article observed that, since other jobs for women paid so poorly, perhaps these female players saw no other option for making a better salary than joining a traveling baseball club. They possibly felt “forced” to put on a gaudy uniform and attempt to play a game they knew so little about. But while claiming to understand their plight, the writer concluded, “We only wish that the same ingenuity which devised this plan could have pointed out to them some other way,” so that years from now, they would not be embarrassed by what they were currently doing to make a living.25

THE WRITERS WHO TRIED TO BE FAIR

As I studied hundreds of articles about the early female baseball clubs of the 1860s-1890s, I found one article that was very different from the usual mockery and dismissiveness. It was from a Sacramento, California newspaper, but written in Boston on October 9, 1883. The column remarked upon the level of the women’s skills, but it also exhibited empathy towards the women themselves, as they tried to learn and improve, often under difficult circumstances. The author was not a sportswriter; she was a correspondent, on her way to Boston in a horse-drawn trolley; and that was where she met the traveling Philadelphia club. She noted that most of them looked “weary,” and she learned that these players were not living a glamorous life. They had been on the road for about a month, playing in city after city; many carried their belongings in shabby suitcases or even cardboard boxes, and they were booked into “third-rate hotels.” Most had formerly worked in the mills or the factories; a few had slight training in baseball before joining the club, but most did not. The next day, the writer noted a large attendance at their game—mostly men and boys, but more than twenty women; and even when the players made mistakes, the crowd seemed enthusiastic and supportive. She wondered, given the sizable crowd, who was making money from this “experiment,” and whether the players were benefiting in any way from their efforts. And she noted that although their game at this point was “poor and unscientific,” they were working very hard at it.26

The only byline said the piece was written by the Sacramento Bee’s “Lady Correspondent,” but after reading her assessment of the “Young Ladies Baseball Club,” I wanted to know more about her. Thanks to some online digging, I discovered the “Lady Correspondent” often went by the pen name of “Ridinghood,” and she was in fact a reporter, who traveled the country seeking stories that would interest the female readers of the paper. Eventually, I discovered her real name: Mary Viola Tingley Lawrence, and while this seems to have been her only story about female baseball players, her work for the Bee and other papers provided an interesting window into the lives of women of the late 1800s.

But while Lawrence was very respectful of the women players, she was not the only one to report on them accurately and fairly. I found numerous articles that were very approving of what female players were doing. In some cases, the positive news reports seemed to result from a well-known local man with a female relative who wanted to play. A good example is the female club that was formed in Peterboro, New York, in 1868. The captain of the club was referred to as the “granddaughter of Gerrit Smith.” (In some newspapers, they spelled his first name Gerritt.) Smith was an abolitionist and a philanthropist, as well as an advocate for women’s suffrage. Newspapers reported that the local young men came out to watch the young women play ball and “enjoy[ed] greatly acting as spectators.”27 As for the un-named granddaughter’s skills as the captain, we were told that she “handles the club with a grace and strength worthy of notice.” And one person who noticed was famed suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who visited Smith and observed the young women playing ball, while the young men “were quiet spectators of the scene.”28

As it turns out, Smith’s baseball-playing granddaughter was named in a different publication: she was Nannie Miller, whose full name was Anne Fitzhugh Miller, later a widely known advocate for women’s rights.29 A few years later, in 1873, another women’s rights advocate, Victoria Woodhull, seems to have weighed in on women’s baseball, according to this brief mention in an Iowa newspaper: “A female base ball club has been organized in Iowa City. Mrs. Wood-hull has written a letter to say the girls ought to be free to handle the bat and ball if they want to.”30 It would certainly be interesting to find out if other women’s rights leaders of that era had any views on women’s athletics, especially women and baseball.

I was able to find a small number of positive assessments of women’s baseball in 1880s newspapers, although more often than not, comments about how pretty (or not) the players were intruded upon the coverage of who played well, or who won the game. For example, one report on a rare competition between the Philadelphia female club and a male team from Neenah, Wisconsin, in 1885 frequently digressed into remarks about the looks of the female players—who were referred to as “beauties at the bat.” And individual players were described as “exquisite,” wearing uniforms that were “captivating.” Some of the women seemed well aware by this time that promotion (and self-promotion) could be useful: one star player was evidently ill that day and couldn’t play, but she still “consented to appear in uniform… and distribute tastefully printed score cards” at five cents each to the crowd.31

There was also an article that started out mildly negative and was changed into something much more positive by an unknown exchange editor in York, Pennsylvania. The original 1883 article in the Boston Globe reported on the arrival of the female club from Philadelphia. At times, the writer seemed sarcastic— for example, he praised the uniforms, which he said were “very pretty” and he then added, “and so were the wearers, at least some of them.” He also noted, with some amazement, that one of the players actually caught a fly ball, and he said the fielding was generally “ragged.” But at other times, he seemed more favorable—he even pointed out several players who did a solid and professional job. “The two catchers, Miss Evans and Miss Moors, displayed considerable science, and handled the bat in good shape.” The attendees had a lot of fun, cheering enthusiastically when good plays were made. “Miss Evans… made two home runs, and was evidently the favorite of the crowd.” And despite his observations about the varying skill levels of the clubs, the reporter wrote, “And why shouldn’t young women play baseball? There doesn’t seem to be any reason that they can’t.”32 But, interestingly, when the article was reprinted in the York Daily, nearly all of the negative and sarcastic comments were stripped out, leaving a far more positive report than the original version.33 Perhaps the exchange editor knew some of the members of the Philadelphia club or had a daughter who played baseball.

THE WRITERS WHO COVERED THE STARS

As with any sport, some of the stories about the teams focused on problems they were having. In the case of women’s baseball clubs, this sometimes meant being victimized by unscrupulous managers who abandoned them and cheated them out of their earnings, as William Gilmore of Philadelphia did: after his players had finished a game in Worcester, Massachusetts, in early August 1879, he stole the gate receipts and their salaries, and left town.34 Or it meant fending off drunken fans who tried to force their way onto the field to talk with them, or make a pass. And while some locales showed the female clubs hospitality, some did not. According to the Associated Press, one traveling female club that came back from Cuba in 1893 was horrified by how they had been treated: “a mob…attacked the women and tore their clothes,” as well as destroying the American flag the club was carrying.”35 But at least by this time, there were fewer stories that blamed the women for their plight or insisted that they had no business playing baseball.

In fact, by the early 1890s, some of the male reporters who covered the games gradually seemed to grow more accepting of the existence of the female clubs. I noticed that some articles were less derisive and more focused on the game itself. One article about an upcoming appearance by a female traveling club from New York even defended their morality: “…if any one expects to see any thing objectionable or immoral in either dress or action, they will be disappointed.” And the writer issued an invitation for women to come and see the club play, saying they should “lay aside all prejudice or false modesty and see these young ladies play ball, and be convinced that there can be no wrong… for a girl or woman to earn an honest and respectable living in the health-giving game and pastime, the great American National Game.”36

There are several possible explanations for the gradual change in tone: women had been playing baseball for about two decades by this time, and the existence of female clubs was no longer the novelty it used to be. Further, some of the women had become more skilled, and their competent play had earned the (sometimes grudging) respect of the sportswriters who saw them. And several players emerged as stars in the eyes of the press, which helped to give women’s baseball increased credibility.

One of the best-known female stars of the 1890s was Lizzie Arlington (real name: Elizabeth Stride, born in 1877 in Mahanoy City, Pennsylvania; some assertions that her birth name was Stroud are incorrect, according to documents available on Ancestry.com and elsewhere). In early September 1891, Arlington and her team from Cincinnati played at the Jefferson County (New York) Fairgrounds. Similar to how other reporters had discussed the female clubs, the local reporter noted that “the girls… played ball as well as they knew how, which was not very well,” and he stated that few in the crowd expected much from the female players, so nobody was disappointed. On the other hand, the writer had to acknowledge that several members of the club actually knew how to play. He praised the catcher, he praised several of the baserunners, and he stated, “the girl pitcher was really a good ballplayer.”37

This favorable assessment would be one of many accolades Arlington would receive during her career, even from men who had previously been skeptical about the ability of woman athletes. For example, in a July 1892 game, the reporter was almost totally focused on Lizzie’s team and how well it played. There was no mention of the uniforms or who was cute and who was not. The game summary could have been written about any men’s team. It featured statements like “Miss Lizzie Arlington, the young lady who has gained considerable notoriety for her phenominal [sic] playing, covered second base… and never did a ball pass that point if it was thrown or batted within her reach. She played with science, and thoroughly understood every rule of base ball playing.” And there were some good plays from other members of the club, which caused loud cheers from the crowd that attended. Of course, given the times, it was not surprising for the writer to conclude by mentioning that the female players “were well-behaved and won the admiration of all with their lady like manner.”38

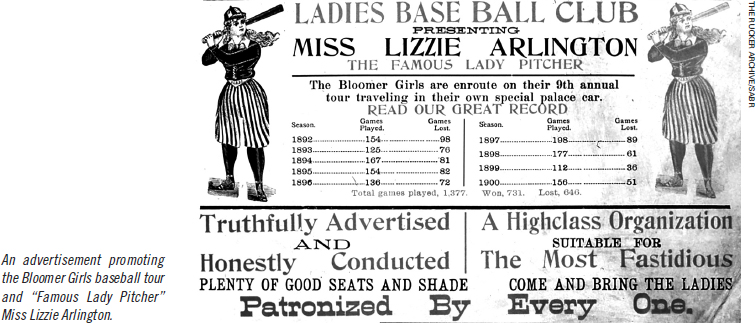

In subsequent articles about any team Arlington was on, she became the focus. Praise of her skills often included the expected “for a woman,” but at least the reporters acknowledged that she was a good player. For example, “She has a wonderful arm for a woman, and the opposing batsmen could not connect with her wide curves and speedy outshoots.”39 In fact, Lizzie was frequently said to be the only female pitcher who could throw a curve ball, and by the mid-to-late 1890s, she was often referred to as the “great female baseball player” or the “phenomenal lady pitcher.” Interestingly, this terminology seemed to be used as a branding device in newspaper ads: she had become a drawing card, and in some cities, there were ads letting the public know that “Lizzie Arlington, the phenomenal lady pitcher” was coming to town.40 As further proof of her success, exchange editors in other cities began reprinting articles about her exploits—something they had rarely done about other women ballplayers. Except for stories about things that went wrong, the members of female ball clubs seldom got much traction with the editors, who evidently believed their readers wouldn’t be interested…but Arlington was considered interesting and unique, and readers from all over the eastern United States were able to learn what she was up to.

The same was true for the other widely respected female baseball star of that era, Maud Nelson (real name, Clementina Brida),41 pictured in newspaper ads as “the famous pitcher of the Bloomer Girls Base Ball Company.” While the Bloomer Girls attracted some disapproval from traditionalists who objected to women wearing pants, the reporters who covered their games focused mainly on what Nelson did, since she was perceived as the one female player who excelled at baseball. As with Arlington, Nelson was treated with a combination of amazement and admiration by the press. The male reporters were pleasantly surprised that she could pitch so well—“better… than it would ever be supposed any woman could ever become,” said one.42 It did not seem to alter their generally negative impression of female players, however. Said one writer, remarking on the fact that the Bloomer club played against male opponents, “The Bloomer girls sometimes win by their opponents not trying to play, [by] flirting on the bases, etc.”43 But Nelson was the exception: most writers still had little that was positive to say about the female clubs, but they had a lot that was positive to say about her. One writer, after noting that she pitched a full nine-inning game, something many male pitchers could not do, remarked that “She threw the ball like a man, and the local team found it a hard thing to hit. She could field well, run bases and bat, and if the Boston Bloomers had nine players like her, they would have made it interesting.”44 And another reporter referred to her with adjectives like “expert” and “clever,” as he told how she struck out male batters with her “puzzling” curveball. The writer also called Nelson’s team “thoroughly professional.” But as in most other articles about the female clubs, there was the reminder that the players had good manners, and they were “lady-like in all their behavior.”45

NEW CENTURY, OLD STEREOTYPES

If we examine the newspapers of 1900-15, we continue to find similar patterns. The new century brought new names: it seems each city had at least one “lady baseballist” who stood out. But the coverage remained relatively unchanged—it was not as negative as in the 1870s and 1880s, but it still treated the women who played baseball as generally not very talented. Reporters focused on the one or two players who were considered the exceptions—the ones who came closest to the male standards for playing the game. And in this era, there was a young woman who proved to be a strong advocate for women’s baseball: her name was Caroline (spelled Carolyn in some sources) “Carrie” Kilbourne, a “girl pitcher” from New Brunswick, New Jersey, who first attracted press attention in 1910-11 while she was still in high school. The local reporters were very impressed: they often spoke of her “unusual ability to play baseball.” And former major league outfielder Willie Keeler, who had also watched her pitch, stated that she was “the most wonderful girl athlete he ever saw.”46

As with the attention paid to Gerrit Smith’s granddaughter Anne, the fact that Carrie’s businessman father Isaac W. Kilbourne was well known locally may have contributed to the positive press attention she received, although certainly her skill as a ballplayer helped. (By some accounts, she wanted to pursue a career with a female baseball club; but her father was opposed to the idea, so she focused on pitching in local exhibition and charity games, as well as doing some umpiring.)

Ultimately, in 1913, Carrie got her chance to pitch for a touring team, which played some exhibition games in Puerto Rico. When she returned, she told reporters she was more convinced than ever that women should play baseball. “Baseball…should be one of the pastimes for the ladies, whether they are young or old,” she said, explaining that it was a healthful way to get exercise. She hoped that from a young age, girls would be able to form their own teams, whether as amateurs or as semi-pro players like the Bloomer Girls. She suggested that aspiring young women could “practice each evening, and in this way, many benefit games could be played for charitable organizations.” And she said she still enjoyed playing. “I would rather play baseball than eat.”47

FINAL THOUGHTS

As baseball moved into the 1920s and 1930s, there were new female “stars” who emerged, including Jackie Mitchell and Lizzie Murphy, and they too received considerable attention from the sportswriters. However, the larger question of whether women had a place in baseball remained unanswered. The women who were discussed positively still seemed to be regarded as exceptions or curiosities. The attitude that baseball was a man’s game persisted, with most baseball writers following the customs of those from fifty years earlier and writing about even the best of the women players in a somewhat patronizing manner. The binary of women ballplayers as either marvels (impressive, with unique talent “for a woman”) or menaces (interlopers, trying to “act like a man”) could still be seen on any sports page. More acceptance might come for women ballplayers one day, but it was wishful thinking to believe it would happen any time soon, wrote one reporter (a woman), who predicted that maybe in another fifty years, there might be some women who could play as well as men. But for now, those women did not exist.48

In recent years, I have been encouraged to see more research being done on the Bloomer Girls and other women’s baseball teams; but exploring what the press had to say about female ball clubs and female players, from baseball’s formative years to the present day, is still an under-researched aspect of baseball history. I know that this article has only scratched the surface: it was written about an era when reporters had no bylines, making it difficult to compare the views of certain sportswriters, or see if those views changed over the years. Thus, I am eager to continue analyzing the sportswriters of the 1930s, 1940s, and beyond, to see if any of them came to believe that women players had genuine talent, or if they maintained the belief that a baseball diamond was no place for a woman. And now that an increasing number of newspapers and magazines are being digitized, they are providing baseball historians with a potential goldmine of new information, helping us to learn more about when (and why) attitudes towards female ballplayers changed… as well as showing us the role the media played in how those changes occurred.

DONNA L. HALPER is an associate professor of communication and media studies at Lesley University in Massachusetts. She joined SABR in 2011, and her research focuses on women and minorities in baseball, the Negro Leagues, and “firsts” in baseball history. A former radio deejay, credited with having discovered the rock band Rush, Dr. Halper reinvented herself and got her Ph.D at age 64. In addition to her research into baseball, she is also a media historian with expertise in the history of broadcasting. She has contributed to SABR’s Games Project and BioProject, as well as writing several articles for the Baseball Research Journal.

Notes

1. Debra A. Shattuck, “Bats, Balls and Books: Baseball and Higher Education for Women at Three Eastern Women’s Colleges, 1866-1891, Journal of Sport History, Summer, 1992, V19, #2, Summer, 1992, 91-92.

2. “The Female Base Ball Club,” Poughkeepsie Journal, October 3, 1875, 1.

3. Albert G. Spalding, America’s National Game, New York: American Sports Publishing Company, 1911, 3-4.

4. laura Pappano, “Reviewed Work: Stolen Bases: Why American Girls Don’t Play Baseball by Jennifer Ring,” The Women’s Review of Books, V26, #6, November/December 2009, 13.

5. Carroll Smith-Rosenberg, “Puberty to Menopause: The Cycle of Femininity in Nineteenth-Century America,” Feminist Studies, V1, #3/4, Winter/Spring, 1973, 62.

6. Shattuck, 91-92.

7. Shattuck, 99.

8. Kimberley Neuendorf, The Content Analysis Guidebook (Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, 2002), 1.

9. “News Notes,” Dayton Herald, August 29, 1883, 3.

10. “All Sorts and Sizes,” Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, August 3, 1870, 4.

11. “Something New,” Highland Weekly News (Hillsboro, Ohio), September 5, 1867, 1.

12. “Miscellaneous Items,” Reno Evening Gazette, September 11, 1879, 1.

13. From the opinion page, Columbia Daily Phoenix, September 9, 1870, 2.

14. “Odd Items from Everywhere,” Boston Globe, May 4, 1886, 8.

15. “Diamond Dashes,” Saint Paul Globe, July 8, 1886, 8.

16. Untitled editorial, Harrisburg Telegraph, September 23, 1875, 1.

17. Untitled editorial, Harrisburg Telegraph, September 24, 1875, 1.

18. “From Monday’s Daily Press,” Saturday Evening Press (Menasha, Wisconsin), August 27, 1885, 3.

19. “Where Are the Police?” Knoxville Sentinel, August 9, 1893, 2.

20. Opinion page, Kansas City Times, July 12, 1879, 4.

21. Leslie A. Heaphy, “More than a Man’s Game: Pennsylvania’s Women Play Ball,” Pennsylvania Legacies, V7, #1, May 2007, 24.

22. “Women and Base-Ball,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 13, 1878, 8.

23. “Crowd at Oakdale,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 5, 1879, 2.

24. “Women Playing Ball,” Philadelphia Times, July 5, 1879, 1

25. “Female Base-Ball Club,” Pittsburgh Post, August 16, 1875, 3.

26. “Our Boston Letter: A ‘Young Ladies Baseball Club’ Visits the Hub,” Sacramento Bee, October 20, 1883, 1.

27. “News in Nut-Shells,” Fall River Daily Evening News, August 14, 1868, 2.

28. “Gerrit Smith at Home,” Lancaster Gazette, October 15, 1868, 1.

29. Tom Gilbert, “Baseball, Fathers, and Feminism,” How Baseball Happened, July 27, 2020, accessed March 10, 2022. https://howbaseballhappened.com/blog/feminism-and-baseballs-founding-fathers.

30. “Iowa Items,” Sioux City Journal, May 1, 1873, 2.

31. “Girls Playing Base Ball,” Rutland Daily Herald, September 10, 1885, 2.

32. “Winding Up the Season,” Boston Globe, October 9, 1883, 2.

33. “The Blonde and Brunette Base-Ballists,” The York Daily, October 20, 1883, 1.

34. “Unfortunate Ending of a Female Baseball Club’s Tour,” New York Daily Herald, August 6, 1879, 5.

35. “Female Ball Players,” Los Angeles Evening Express, March 15, 1893, 2.

36. “Young Lady Baseballists,” Meadville Evening Republican, September 2, 1891, 4.

37. “Petticoats Playing Base-Ball,” Watertown Daily Times, September 3, 1891, 8.

38. “Female Base Ball Club,” Mt. Carmel Register, July 21, 1892, 4.

39. “The Pretty Girl Won,” Pittsburgh Press, May 21, 1898, 6.

40. See for example, the Lancaster Morning News, July 27, 1898: 4.

41. Barbara Gregorich, Research Notes for Women at Play: The Story of Women in Baseball, Vol. III, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015, 1, 21.

42. “Very Good for Girls,” Arizona Republic, November 23, 1897, 1.

43. “Boys vs. Bloomers,” Albany Democrat (Oregon), October 15, 1897, 1.

44. “Only One Girl Player,” Anaconda Standard, September 7, 1897, 5.

45. “Surprised Opponents,” The Journal and Tribune (Knoxville, Tennessee), June 13, 1900, 6.

46. “More Honor for Carrie Kilbourne,” Central Home News (New Jersey), August 11, 1911, 9.

47. “Miss Kilbourne, of Baseball Fame, Declares Girls Should Play the National Game.” Passaic Daily Herald, August 12, 1913, 8.

48. Jubeth Gorman, “Was Babe Ruth Really Trying?” Chattanooga Daily Times, February 12, 1933, M7.

![This illustration of Lizzie Arlington, based on her collectible cabinet card, appeared in 1898 with a caption that read, "Women's inability to throw has long been a fruitful theme for the humorists, but ... [Lizzie] is the exception which proves the rule." (PUBLIC DOMAIN)](https://sabrweb.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/brj22-000057.jpg)