Memphis Bill in Newnan

This article was written by Scott McClellan

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Peach State (Atlanta, 2010)

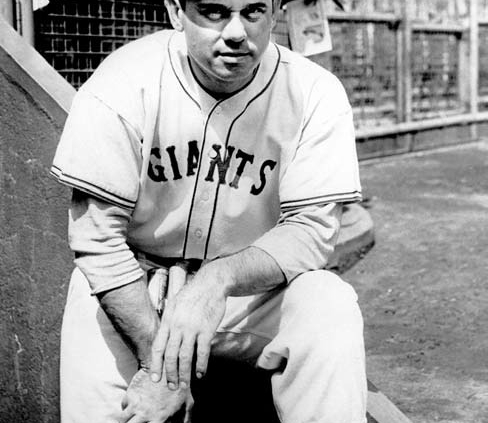

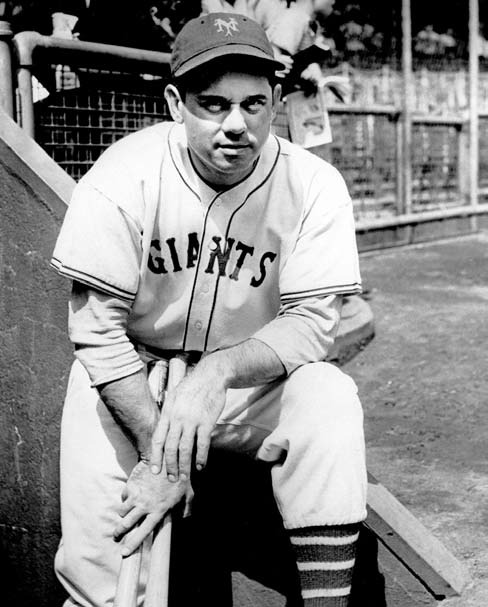

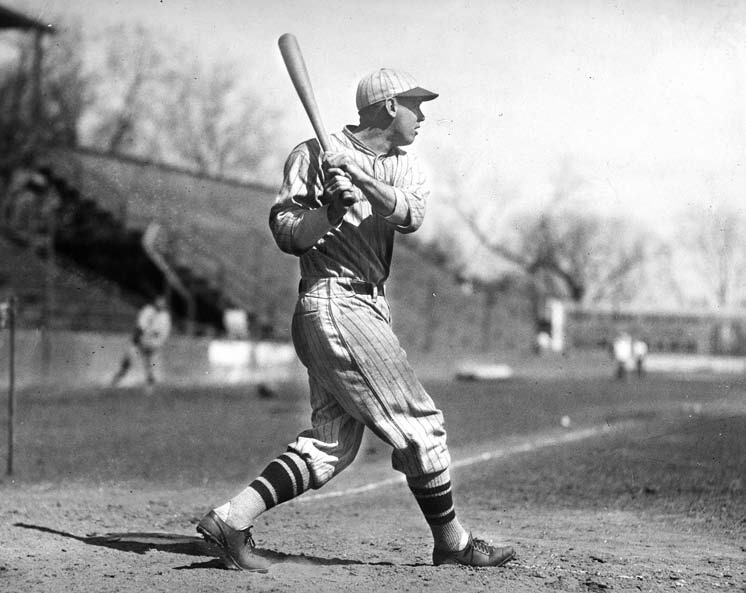

As the last National League player to bat .400 in a season, Bill Terry is best remembered for racking up hits for the New York Giants. But in 1915 in the Georgia-Alabama League, he showed he could also be good at preventing them, too.As the last National League player to bat .400 in a season, Bill Terry is best remembered for racking up hits for the New York Giants. But he showed he could also be good at preventing them with the no-hitter he threw in 1915, when he went 7–1 as a pitcher for the Georgia-Alabama League club in Newnan, 39 miles from the Atlanta neighborhood where he was raised.[fn]Lowell Reidenbaugh, Baseball’s Hall of Fame: Cooperstown (New York: Arlington House, 1986), 301.[/fn]

Terry was born into a prominent Atlanta family. His great-grandfather, Tom Terry, ran the only sawmill in the city before he died from injuries sustained in an assault. His grandfather, William M. Terry, was an alderman, police commissioner, and founder of the Decatur Street Bank—and did so well that he bought a large house a few blocks from the Atlanta Crackers’ ballpark.[fn]Peter Williams, When the Giants Were Giants: Bill Terry and the Golden Age of New York Baseball (Chapel Hill, N.C.: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1994), 17–20.[/fn] Terry’s father, William T. Terry, was less successful and moved his family in and out of his father’s house several times before settling there permanently around 1915. By that time Terry’s mother, Bertha, had left for good, and he was ready to strike out on his own. He had little contact with his parents after that time, and neither of them attended his Memphis wedding to Elvena Sneed, who grew up in the same area of Atlanta as Terry.[fn]Ibid, 22.[/fn]

The young Terry sometimes sought escape by watching Crackers’ games from the trees beyond the outfield fence—when he wasn‘t busy loading trucks at the railroad yard to make money or playing for the Edgewood Avenue squad in the Grammar School League. However, he had a much closer view of the field in 1914, when the Crackers signed him to his first pro contract on the recommendation of former Cracker Harry Matthews. Terry worked out in the park but did not get into any games that year. “During the early practice at Ponce de Leon” the next year, according to the Atlanta Journal, “he showed a bunch of stuff, and older members of the team predicted that he would develop into a great pitcher with a few years of experience.”[fn]Atlanta Journal, 1 July 1915.[/fn] But Terry was only sixteen at the time, and he struggled with his control. The Crackers farmed him out to Dothan, where he suffered through a terrible start to the season, with an ERA over 15.00 in his brief time in the Florida–Alabama–Georgia (FLAG) League. But Matthews still liked the hard-throwing youngster and arranged to sign him for his Newnan team, where Terry played his first game on June 16.[fn]Atlanta Constitution, 17 June 1915.[/fn]

The star pitcher on the Newnan team was Jack Nabors, who led the league with 12 wins in 1915,[fn]The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, N.C.: Baseball America, 1993), 142.[/fn] but Terry began to attract attention in his own right after his no-hitter on June 30. According to the Newnan Times-Herald:

Scout Bobby Gilks, of the New York Americans, was in Newnan yesterday looking over Pitcher Jack Nabors, who recently twirled the 13-inning no-hit game against Talladega. Mr. Gilks was in Anniston last Wednesday to observe the work of Pitcher Glazier [sic], of the Anniston team; but while there he saw Southpaw Terry, of the Newnan team, shut out the Moulders in a hitless game. We understand that Mr. Gilks was sent here to watch Pitcher Nabors in action, but since young Terry has risen to a place in balldom’s hall of fame he will have two of Newnan’s pitchers under observation.[fn]“Baseball, Baseball, Baseball!” Newnan Times-Herald, 2 July 1915.[/fn]

Terry later remembered “the last guy up hit a line drive into right field, and I knew it was a no-hitter, you know, and it scared me; but the right fielder came up with it, anyway.”[fn]Williams, 29.[/fn]

The Newnan paper opined the no-hitter was “due to the coaching of Matthews,” [fn]Ibid.[/fn] who had seen Terry pitch in Dothan and was determined to teach him to pitch to spots. When Terry joined the Newnan club, Matthews took him to a drug store and bought a bottle of ink that he used to mark a spot in the middle of his chest protector. Matthews told Terry he was to throw to that spot no matter how Matthews set up— with good results.[fn]Ibid, 31.[/fn] The importance of having a target like this should not be discounted: the authorities at Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam had the image of a housefly etched into the middle of each urinal at the facility—and later found spillage was reduced by 80 percent.[fn]Richard H. Thaler and Cass Sunstein, Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 4.[/fn] Terry’s control did improve during his first season pitching for Newnan; he walked only 1.9 batters per nine innings in his eight starts for the club, while striking out 4.0 batters per game. Terry did not allow more than two runs in any of his starts, four of which were shutouts.[fn]Robert C. McConnell, “Bill Terry As Pitcher,” In 1989 Baseball Research Journal, 53.[/fn]

Newnan won the pennant with a 39–20 record, beating out Talladega, which finished 39–22. Matthews was awarded fifty dollars in gold by Newnan fans before the final game of the 1915 season, which Terry won 1–0 ,[fn]Ibid.[/fn] as Newnan defeated LaGrange for the 11th time in as many games that year. After receiving the gold, Matthews told his Newnan fans that their town was the best he’d ever played in.[fn]“Newnan Winds Up Ball Season in a Blaze of Glory,” Newnan Times Herald, 16 July 1915.[/fn] Terry seemed to enjoy his time with Newnan as well. He later remembered a night when he and three friends, all of whom could sing well, went to the fair in Anniston and walked around the fair, singing and taking in the sights. Matthews was waiting up for them when they returned to the hotel, wanting to see what kind of shape they were in, and found they had enjoyed themselves without touching alcohol.[fn]Williams, 29.[/fn]

Terry pitched for Newnan again in 1916, compiling an 11–8 record for a second-place team. After the short-season Georgia-Alabama League ended play on July 21, his contract was purchased for the stretch drive by the Shreveport club in the Texas League, and he went 6–2 over the rest of the season for a team that missed a pennant by a single game. Terry went 14–11 for Shreveport in 1917 but no longer saw much of a future in minor-league baseball.[fn]Ibid, 31.[/fn] Over breakfast at a Shreveport coffee shop, Terry and his wife decided that he would seek a more promising line of work if he didn’t receive any major-league offers.[fn]Reidenbaugh, 244.[/fn] He did not, and so he went to work for Standard Oil, first as a clerk and eventually as a salesman. While working there, Terry managed and played for the company baseball team until 1922, when he finally got his major-league offer.

John McGraw, acting on the recommendation of former big-league shortstop Kid Elberfeld, wanted to sign Terry.[fn]Red Barber, “Bill Terry Remembers John McGraw,” In From Cobb to Catfish: 128 Illustrated Stories from Baseball Digest (New York: Rand McNally), 89.[/fn] Typically, Terry asked, “For how much money?” When McGraw pointed out he was offering an opportunity to play for the New York Giants, Terry responded: “That doesn’t mean a thing to me, Mr. McGraw. I’ve got a wife and baby to support. I quit in the minors because it didn’t pay enough. I’ve got a good job with Standard Oil and a nice house here in Memphis. If the Giants make me a better offer, all right.”[fn]Lee Allen, The Giants and the Dodgers, the Fabulous Story of Baseball’s Fiercest Feud (New York: Putnam, 1964), 151.[/fn] Fortunately for both, they came to an agreement.

Terry sometimes gave McGraw the credit for his move to first base, but at other times insisted it was his own idea. In any case, Terry made the most of the change. The Sporting News described him as the “leading batter in the National League” when announcing him as National League MVP for 1930.[fn]The Sporting News Record Book for 1931 (St. Louis: Charles Spink and Son, 1932), 42.[/fn] Longtime sportswriter Fred Lieb, in choosing the greatest first baseman from 1926 to 1950, would not “declare anything other than a tie. Lou [Gehrig] had a clear edge in every batting statistic except lifetime average, where Memphis Bill edged him, .341 to .340. But Bill Terry was the greatest fielding first baseman I ever saw.”[fn]21. Fred Lieb, Baseball As I Have Known It (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996), 276.[/fn] This was high praise from a man who saw most of the great players of the twentieth century, especially since he was a close friend of Gehrig.

Life after baseball was also good for Terry, who was married for 67 years and said he never fell out of love with his wife.[fn]Williams, 26.[/fn] Keeping a home in Memphis after his wedding, Terry bought and sold real estate in the area quite successfully during his playing career and parlayed the profits and his baseball earnings into a fortune. He eventually owned a Buick dealership in Jacksonville, Florida, and worked there right up to his death at age 90. Terry proved he could excel at many positions.

SCOTT MCCLELLAN has been a SABR member since 1988. He works as a land-title examiner when not attending Braves’ games.