Merle Harmon

This article was written by Maxwell Kates

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 27, 2007)

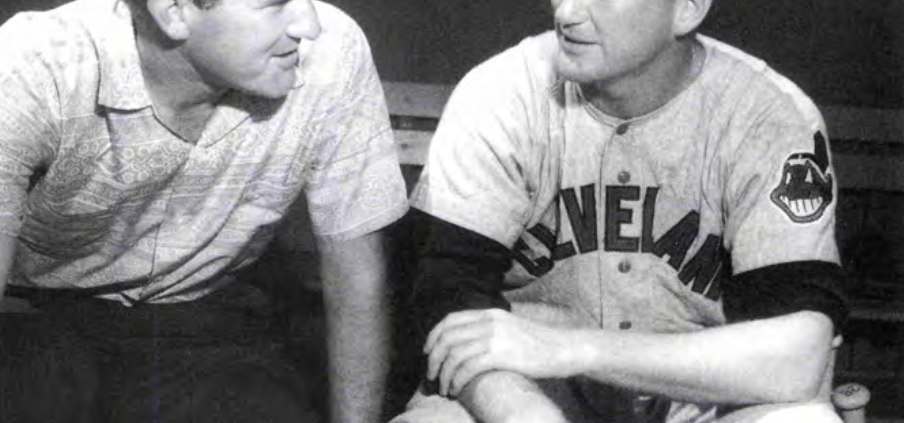

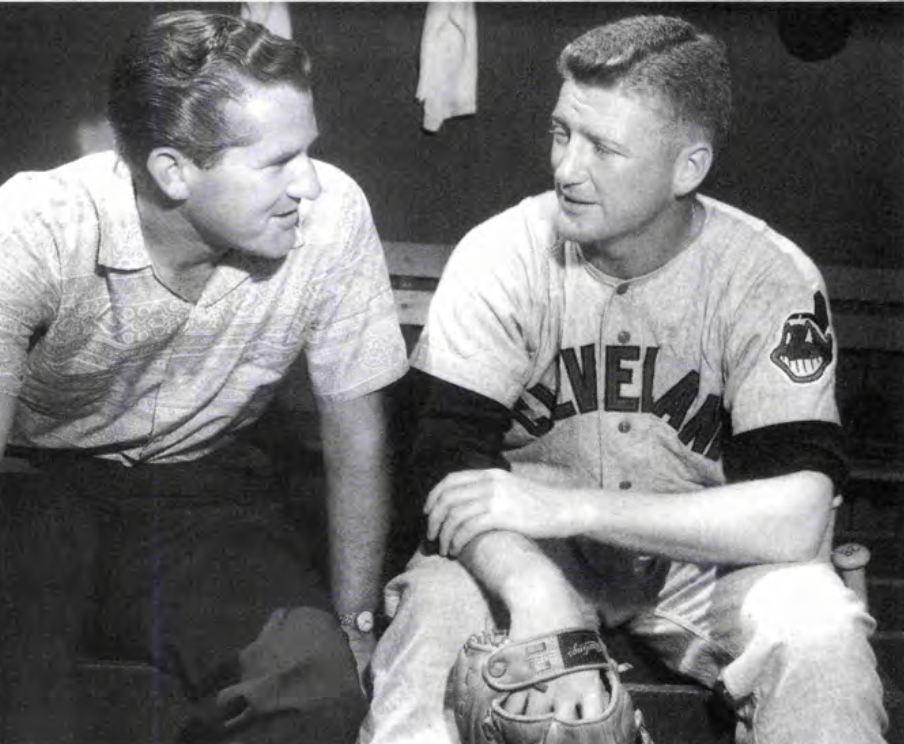

Merle Harmon interviews Herb Score. The 1955 American League Rookie of the Year winner later joined the baseball broadcasting fraternity after his career ended prematurely. (COURTESY OF MERLE HARMON)

He was a sports broadcaster and former college football player from the Midwest. Tall and gray haired, he sported a crooked nose as a football injury badge. Answering to the name Harmon, he called gridiron action working for ABC telecasts. It would be understandable. to many if he were often mistaken for the great Tom Harmon of Michigan, particularly if his broad casting partner were former Wolverine footballer Forest Evashevski. Would you believe this misunderstanding actually occurred at a banquet prior to an Alabama Mississippi game in Birmingham? The emcee even misintroduced the mike man as Tom Harmon. After assuming the podium, the broadcaster handled the scenario with class and professionalism. Even his posture and his diction were dead ringers for Tom Harmon. “But I ask you,” he proclaimed, “who is this guy standing before you? Is he Tom Harmon, the great Michigan All America and Heisman Trophy winner? If you’re saying yes, then the gag’s on you. I’m the other guy.”

Just who was “the other guy?” He was the elder Merle Reid Harmon, and he was in the ninth grade when Tom Harmon won the Reisman Trophy in 1940. Merle played college football, but never reached the professional ranks. He served his country during the Second World War, but not as an Air Force pilot. Although he worked in movies, “not one soul has ever mentioned seeing me in one.” And, no, his children were never married to Pam Dawber or Rick Nelson. The preceding anecdote summarizes Merle’s executive summary well-a knowledge of sports, a love of people, an acumen for broadcasting, and a sense of humor, allowing him to laugh at himself when necessary.

Merle was born on June 21, 1926, in Salem, Illinois, the son of a greengrocer. During his childhood, his impoverished economic situation was far from unique among Americans. Raised as a member of the Community of Christ, Merle retained his values of family and faith throughout his career and during his subsequent retirement. Growing up 60 miles from St. Louis, the Cardinals naturally became his favorite team. Although he loved to listen to the antics of Dizzy, Daffy, Leo the Lip, the Arkansas Hummingbird, and the Wild Hoss of the Osage, his child hood hero was the broadcaster France Laux.

As a high school student, Harmon sold magazines door-to-door to help his family during the summer. He kept $2 for himself, enabling him to budget a trip to St. Louis to see the Cardinals play at Sportsman’s Park. Round-trip train fare cost $1, streetcar tickets cost a dime each way, a bleacher seat was worth a quarter, and a hot dog, a soft drink, and a bag of peanuts set him back an additional 30 cents. At the end of the day, Merle was left with a quarter, just enough to purchase a team pennant and a Cardinals pencil. Returning to school in September, he remarked, “I protected that pencil with my life, making sure my friends saw it and asked me where I got it. As a poor kid in the Depression years, that pencil was my status symbol. It was proof that I had been to St. Louis to see a big league baseball game.”

Young Merle enlisted in the United States Navy in 1944, serving on a troop-landing craft in the South Pacific. Following the Allied victory, he registered as a student at Graceland College in Iowa. It was there as a sophomore in 1946 that he met a freshman co-ed named Jeanette Kinner. Merle immediately confided in his cousin, “Glen, you see that girl over there? I’ m going to marry her!” Although Jeanette was unofficially engaged to another man, it was Merle who ultimately won her heart. Merle and Jeanette were married on December 31, 1946. They raised five children, Merle Reid Jr., Keith, Kyle, Bruce, and Kara, and presently have grandchildren living across the country.

After graduating from the University of Denver with a bachelor’s degree in radio in 1949, Merle began his career in Kansas as the voice of the Class C Topeka Owls. Although the Great Depression was long over, the Owls continued to live and travel frugally. Meal money was $1 per day and the lodging allowance was $3- a sum which could not buy an air-conditioned room on the road. The team bus would have fit perfectly on the set of Little Miss Sunshine. Carrying 17 players, the bus traveled at a maximum speed of 40 miles per hour downhill — and often had to be pushed to a service station for refueling. Money was so tight that the players even resorted to brawling to determine who got to drive the bus for a stipend of $50 per month.

Needless to say, conditions on the road were enough to make basic needs such as sleep seem luxurious. Harmon’s baptismal in minor league broadcasting occurred in late July as the Owls were in St. Joseph to play the baby Cardinals-led by a fiery second baseman named Earl Weaver. Merle worked nearly eight hours of a doubleheader as a broadcaster and technician in triple digit heat despite a splitting headache. Amid a comedy of errors, hits, runs, passed balls, and wild pitches in the second game, Merle. pleaded with the radio audience for forgiveness for “not being able to go all out on the broad cast tonight. You know how it is with a bad headache.” As he told Nick Purdon of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in 2004, the fans were not sympathetic. One woman even sent Merle a postcard — “Don’t tell us your troubles. Broadcast the game!” It was the most important piece of professional advice that he ever received.

Merle remained in Topeka through the 1952 season, and recalled his highlight in the Kansas state capital the opportunity to see a young shortstop for Joplin in 1950 who “at 18 … already hit balls out of sight.” The Oklahoma Kid in question was none other than Mickey Mantle. Merle also began broadcasting football, basket ball, and track and field for the University of Kansas. By 1954, he earned a promotion to the Kansas City Blues of the American Association. That November, Chicago banker Arnold Johnson bought the Philadelphia Athletics from the debt-ridden Mack family. To Merle’s surprise, Johnson intended to retain him as the Kansas City broadcaster in 1955 after moving the Athletics from Philadelphia. Merle credited the tireless campaigning of Ernie Mehl for successfully bringing an American League team to Kansas City. After Johnson died in 1960, Chicago insurance magnate Charlie O. Finley purchased 52 percent of the team from his estate. The following year, Finley organized “Poison Pen Day ” to admonish Mehl, sports editor of the Kansas City Star. Outraged, Merle boycotted the event. “Ernie got baseball here in ‘ 55 — and Finley’s trashing him!” By valuing loyalty to his convictions ahead of his employer, Merle was fired from the Athletics in 1961.

Merle would not be looking for work for long. In August 1961, the Athletics were visiting the Yankees in New York. After broadcasting the baseball exploits of Roger Maris the night before-along with several other Athletics alumni now uniformed in pinstripes — he received a phone call early one morning. Half-asleep, he heard the voice on the other end ask, “Would you be interested in doing a national sports show for ABC television?” Disbelieving the sincerity of the other gentleman, Merle assumed it was a player making a crank call. Merle responded by directing him to contact his agent. The other man responded with “…we’d be glad to contact him, but we’d like to see you because we’re leaving for Chicago today to do the [football] All-Star Game.” This was no player. Rather, it was Chet Simmons of Sports Programs, a department of ABC Television. Thus began a 12-year working relationship with ABC for Merle. Each weekend the network would import him to New York from his home in Kansas City to broadcast programs such as Saturday Night Sports Final and College Football Scoreboard.

In 1965, Merle’s duties with ABC were expanded to include Game of the Week baseball contests. He opened the season in Boston, where he proudly witnessed his color commentator break the color bar for broadcasting. Who called the game with Merle? Jackie Robinson, that’s who. Ironically, the game was played at Fenway Park, the very ballpark where he was denied the opportunity to play for the Red Sox two decades earlier. From 1963 to 1972, Merle also broadcast football play-by-play on radio, first for the Kansas City Chiefs and then for the New York Jets.

Although Merle’s broadcasting career took him to dozens of outposts, he is perhaps most associated with the city of Milwaukee. He worked for the Marquette University basketball team as well as the Braves and Brewers. Cream City had been baseball’s veritable hotbed when the Braves moved from Boston in spring training 1953. The Braves drew better than two million fans in each of the four years that followed, shattering their own National League attendance record in 1957 — the year “Bushville” upset the Bronx Bombers for the world championship. Ultimately, the Braves fell from contention, Milwaukee County Stadium barred fans from bringing their own beer, and by 1963 attendance fell below one million. To the radio audience at home, broad caster Earl Gillespie had been as integral to the Milwaukee Braves as Warren Spahn, Eddie Mathews, or Hank Aaron, but even he could read the writing on the wall. When Braves president Louis Perini sold the club to a syndicate led by William Bartholomay, Gillespie submitted his resignation.

Merle accepted the post, but it was a thankless position. Although the Braves contended in 1964, the season was clouded by rumors surrounding the team’s future in Milwaukee. Only a court order in 1965 prevented them from jettisoning the Dairy State for greener pastures in Georgia. Broadcasting Braves games during a lame duck season became a veritable Catch-22 for Merle. “They had to play …in a city which knew it was losing them. If I praised the Braves, people said ‘Don’t root for traitors.’ If l didn’t, diehards said, ‘Don’t mess up another club.”‘ Despite once again contending well into September, the Braves attracted only 555,584 spectators to Milwaukee County Stadium before departing for Atlanta. On the other hand, calling Braves games allowed Merle the opportunity to work alongside Mel Allen during the 1965 season. How about that!

That final weekend of the 1965 season marked one of the most tumultuous of Merle’s career. The Braves were visiting the first-place Dodgers in Los Angeles. Meanwhile, the second-place Giants, hosting Cincinnati, had not yet been eliminated. After calling the Dodgers game on Friday night, Merle would air the final Game of the Week for ABC on Saturday. The trouble was that as Friday dawned, he still did not know where he would be working the following day. If the Dodgers won and clinched a tie, he would fly to Cleveland to broadcast the Indians. If the Dodgers lost, he would travel to San Francisco. Merle had an outside chance of flying to Chicago to catch a connecting flight to Minneapolis, where he would broadcast the Twins, champions of the. American League. The only place he was certain of not working was Los Angeles, as it would pose a conflict of interest for the Milwaukee announcer to call a Braves game on network television.

Merle had reserved flights for San Francisco, Chicago, and Cleveland, but he could not board any until the Dodgers game had concluded. As it happened, the game was scoreless entering the 10th inning. Hurriedly catching a cab, he asked the driver to turn on the game. He arrived at the airport during the 12th inning-the game was still scoreless. The driver asked, “Which terminal you going to?” Merle replied, “I don’ t know.” In a scene reminiscent of Howard Jarvis as a taxi passenger in the movie Airplane, Merle asked the driver to pull over and listen to the game. The meter was still running. Finally, the Dodgers won — Merle was boarding a United flight to Cleveland. The plane was ready to taxi as he arrived at the terminal. In an era less constrained by security restrictions, Merle hurdled over the conveyor belt and ran through the baggage room before finally reaching the plane as the doors were set to close. Only then did he realize he was going to the wrong city — “I’ m supposed to be in San Francisco!” He panicked. Arriving in Cleveland hours later, Merle’s fears were eased by ABC executives when they told him he had indeed flown to the correct destination.

Following a one-year hiatus from baseball, he returned in 1967 to work for the Minnesota Twins. Slugging infielder Harmon Killebrew propelled the team to an Opening Day victory with one of his 573 career home runs. Following the game, a fan exclaimed, “Nice game, Harmon” while passing Merle. In another case of mistaken nomenclature, the broadcaster had no idea that Killebrew was walking immediately behind him.

Working in the Twin Cities allowed Merle the opportunity to broadcast games alongside Halsey Hall. A Minnesota baseball legend since the 1930s, Halsey adopted “Holy cow!” as his signature call while Harry Caray and Phil Rizzuto were still children. Where Halsey and his trademark cigars traveled, humor was certain to follow, as was the case during a Sunday doubleheader at Comiskey Park. Excited by a fifth-inning rally, Halsey accidentally knocked his lit cigar off his desk, igniting afire in the broadcast booth. As Merle described the situation years later, Halsey proceeded to stomp the fire with his feet, creating a unique dance step, albeit not quite ready for American Bandstand. Later in the game, Merle noticed that Halsey’s sports coat had caught fire. A consummate professional, Halsey continued to call the game despite a considerable hole charred into his sleeve. As Arno Goethel wrote the following day in the St. Paul Pioneer Press, “Halsey Hall is the only man I know who can take an ordinary sports coat and make a blazer out of it.”

For the second time in three years, Merle broadcast a sudden-death pennant race as the season drew to a close. The Twins were in Boston playing the Red Sox during their “Impossible Dream” summer campaign. In a race also involving the Tigers and the White Sox, Boston proved triumphant. Though privately disappointed, Merle received a reprimanding letter from a Minnesota fan for sounding “… as excited when the Red Sox made big plays as [he] did when the Twins made big plays.” Merle appreciated the disapproval, knowing he had conducted himself properly.

Merle was set to begin his fourth season with the Twins in 1970 when he accepted his release on the eve of the American League season. On April 1, 1970, the circuit transferred the Seattle Pilots to Milwaukee, and Merle was hired to broadcast for the team, which had been renamed the Brewers. The franchise shift was not without a barrage of legal confusion — as outfielder Steve Hovley remembers, “once the team bus got to Salt Lake City, we didn’t even know whether to turn left [to Seattle] or turn right [to Milwaukee].” The bus headed right for the Badger State, leaving barely a week for professional seamstresses to remove the “Pilots” stitching from player uniforms and replace it with”Brewers.” The first home game in Milwaukee on April 7 was a nightmare as Andy Messersmith ofthe Angels decimated the Brewers behind Gene Brabender by a margin of 12-0. Baseball would prove to be a difficult product to sell in Milwaukee the second time around. Only in 1973 did attendance top one million, and another five years would pass before the Brew Crewposted a winning record in 1978.

The early Brewers teams, however, were not without their share of characters and comic incidents, including the time relief pitcher Tom Murphy sent his identical twin brother Roger in uniform into Bud Selig’s office to negotiate his contract. In 1971, Merle welcomed into the broadcast booth a Milwaukee native and former Braves catcher who would soon become a legend throughout Wisconsin.

“Merle Harmon helped me from the start,” recalled Bob Uecker of his rookie season in the catbird seat — many years before playing Harry Doyle in Major League. “I’d never done baseball when I joined him in the booth, not unless you count my play-by-play into beer cups in the bullpen. Beer cups don’ t criticize, [but] people do… Merle and Tom Collins let me do color, then play-by-play, and saved me if I screwed up.”

Uecker, already familiar with the bullpen as a player, achieved a save of his own on March 18, 1971. Visiting the Brewers at their spring training headquarters in Tempe, Arizona, were the Tokyo Lotte Orions. As Merle looked at the lineup, bewildered by the unpronounceable last names, Uecker reassured him that he could handle the situation. After all, Uecker could speak Japanese. Or could he? When it came time to announce the batting order, Uecker introduced the leadoff hitter as center fielder Tom Toyota. Following him in the lineup were Nick Nissan, Sal Subaru, Paul Panasonic, Hank Honda, and Mike Mitsubishi. Merle recalled “Paul Panasonic had quite a day, hitting a three-run homer and belting a two-run double.”

As the decade of the 1970s progressed, Merle explored a variety of business ventures while continuing to expand his versatility as a broadcaster. He was among the founders of a new broadcasting school in Milwaukee. In 1973, Merle had the privilege of broadcasting the World Games from Moscow. When he decided to photograph tourist scenes of the Soviet capital on his personal camera, it generated a skirmish with the KGB. Nevertheless, they were able to arrange a deal-” the KGB got the film and Merle got to go home.” Departing Moscow at 9:00 on a Saturday morning, he called a base ball game in Minnesota that night. While broadcasting World Football League action on August 8 of the following year, Merle had the dubious distinction of introducing Richard Nixon for a speech on national television. The 37th president made it perfectly clear of his intent to resign the next day. Later on, Merle became an elder in the Reorganized Church of Latter Day Saints.

In 1977, Merle undertook perhaps the greatest risk of his career by establishing the first retail store to sell officially licensed merchandise of professional and collegiate sports teams: Merle Harmon’s Fan Fair. The seed was planted in Merle’s conscience over a decade earlier, when he broadcast for the New York Jets. After receiving a Jets desk clock as a Christmas present one year, Merle received dozens of accolades from people asking where they could buy one for themselves. To their chagrin, the answer was “nowhere.” Similarly, fans could purchase Brewers caps only at stadium concession stands. Even then the caps were made from mesh as opposed to the wool hats worn by the players. Team executives were simply uninterested in the idea of allowing casual fans to wear official team property.

Still, Merle knew that consumers were willing to purchase official Brewers caps or Jets desk clocks, and he sought to satisfy them. Following a family discussion, Merle’s son Reid agreed to operate a “sports fan’s gift shop” at a major shopping center in Milwaukee. Three of the other Harmon children followed Reid into the business, and the fans responded. Virtually the entire Brewers team showed up to meet legions of fans as they waited two hours to enter the store. Meanwhile, the dairy across the aisle sold “every scoop of ice cream in the place.”Although the store grossed only $300 that initial day “just enough to pay the electric bill” — it marked one small step for an enterprise which would eventually mushroom into 140 franchises. For his achievements Merle won the 1993 Graham McNamee Award as a broadcaster who excelled in a second endeavour.

Merle’s final year with the Milwaukee Brewers was 1979. Led by manager George Bamberger, the “Brew Crew” won a franchise-record 95 games to finish in second place behind Baltimore. Despite the offensive juggernaut powered by Robin Yount, Paul Molitor, Gorman Thomas, and the rest of “Bambi’s Bombers,” it was time for Merle to move on. Having signed a broad casting deal with NBC which included Game of the Week, the 1980 World Series, and a return trip to Moscow to call the Summer Olympics, he resigned from the Brewers. Alas, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan on December 27, 1979, prompting the United States to lead a boycott of the 1980 Olympiad. On a brighter side, at least Merle did not give the KGB another opportunity to confiscate additional rolls of photography.

Replaced at NBC by the youthful Bob Costas in 1982, Merle returned to the American League as a broadcaster for the Texas Rangers. In Arlington he was united with two old friends. Former Milwaukee Braves manager Bobby Bragan was now the director of the Rangers’ speaking bureau, while the director of television planning was none other than the Wyoming Cowboy himself, Curt Gowdy. The crowning achievement of Merle’s career behind the microphone occurred in his final year as a baseball broadcaster. On August 22, 1989, the Rangers’ legendary right hander Nolan Ryan entered the game with 4,994 strikeouts. Five innings and five batters called out on strikes later, Oakland speedster Rickey Henderson stepped to the plate. When Henderson whiffed and the hometown crowd went wild, Merle used a technique demonstrating that at times, no man is greater than the event — not the broadcaster, not even the pitcher. He said absolutely nothing. “If the event warrants,” he explained,”let the crowd and TV director take over to capture the emotion.” Merle continued to broadcast freelance events before retiring from the profession altogether in 1995.

Merle is one of the most genuine individuals one could ask to work with. Despite several battles with adversity through poverty during the Depression, employment insecurity throughout his career, fan admonishment in Milwaukee, Charlie Finley in Kansas City, and the KGB in Moscow, one would never sense that his life was an obstacle course of unforeseen circumstances. Merle retained his cornerstone values of family and faith from his formative years to senior citizenhood. He would not forget the people he worked alongside, retaining friendships with players, writers, and other broadcasters, including Len Dawson, Bill Grigsby, Wes Stock, and the late Joe McGuff. Merle, who sold the Fan Fair conglomerate in 1996, was inducted into the Texas Baseball Hall of Fame that same year. In 2004, the Salem Community High School — his alma mater in Illinois — inducted him as a charter member in its Hall of Fame. Although Cooperstown has yet to acknowledge Merle with a Ford Frick Award, when his protege Bob Uecker was so honoured in 2003, the Milwaukee broadcaster made certain to credit his mentor in his acceptance speech.

Merle and his wife Jeanette remained in the Metroplex after his retirement from the Rangers, and they continue to live in Arlington. He still conducts daily exercises on his treadmill, and he volunteers one day a week at a local soup kitchen. In an ironic turn of events, Merle may no longer be the second most famous sports personality named Harmon. Several years ago, when the great Harmon of Michigan appeared as a football coach on Bizarre, a variety series hosted by comedian John Byner, at least one spectator was heard asking, “Tom Harmon? Don’t they mean Merle Harmon?”

MAXWELL KATES, at age 12, purchased a Chicago White Sox cap from Merle Harmon’s Fan Fair in Plantation, Florida. When he asked who Merle Harmon was, his mother replied that “the name probably sounds made up. ” Years later, Kates worked with Harmon on a radio broadcasting project, and told him this story. A SABR member since 2001, Kates now works as a staff accountant in Toronto.

Acknowledgments

The author also wishes to acknowledge the following people for their contributions to this essay: Dave Baldwin, Bob Buege, Jeanette Harmon, Steve Hovley, Rich Klein, Bob Koehler, Nick Purdon, Rick Schabowski, Wes Stock, Stew Thornley, and especially Merle Harmon.

Notes

“Hall of Fame Candidates Selected,” Salem Times-Commoner,April 16, 2004.

Aaron, Hank, and Lonnie Wheeler. I Had a Hammer. Scranton, PA: Harper Collins, 1991.

Bryant, Howard. Shut Out: A Story of Race and Baseball in Boston. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Buege, Bob. The Milwaukee Braves: A Baseball Eulogy. Milwaukee: Douglas American Sports Publications, 1988.

Dewey, Donald, and Nicholas Acocella. Encyclopedia of Major League Teams. New York: Harper Collins, 1993.

Harmon, Merle, and Sam Blair. Merle Harmon Stories. Arlington, TX: Reid Productions, 1998.

Hawkins, Burton, ed. Texas Rangers 1982 Media Guide. Arlington, TX: Texas Rangers Baseball Club, 1982.

Hoffmann, Gregg. Down in the Valley: The History of Milwaukee County Stadium – The People, the Promise, the Passion. Milwaukee: Journal-Sentinel and the Brewers Baseball Club, 2000.

Liberman, Adam, et al. 2004 Atlanta Braves Media Guide. Atlanta: Braves Public Relations Department, 2004.

Sears, Bill. The Milwaukee Brewers 1970 Inaugural Yearbook. Milwaukee: Milwaukee Brewers, 1970.

Smith, Curt. The Storytellers: From Me/Allen to Bob Costas — Sixty Years of Baseball Tales from the Broadcast Booth. New York: Wiley, 1995.

Smith, Curt. Voices of Summer: Ranking Baseball’s 101 All Time Best Announcers. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2005.

Thornley, Stew. Holy Cow! The Life and Times of Halsey Hall. Minneapolis: Nodin Press, 1991.